Darboux integral

In real analysis, a branch of mathematics, the Darboux integral is constructed using Darboux sums and is one possible definition of the integral of a function. Darboux integrals are equivalent to Riemann integrals, meaning that a function is Darboux-integrable if and only if it is Riemann-integrable, and the values of the two integrals, if they exist, are equal.[1] Darboux integrals have the advantage of being simpler to define than Riemann integrals. Darboux integrals are named after their inventor, Gaston Darboux.

Definition

Darboux sums

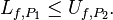

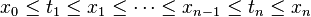

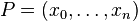

A partition of an interval [a,b] is a finite sequence of values xi such that

Each interval [xi−1,xi] is called a subinterval of the partition. Let ƒ:[a,b]→R be a bounded function, and let

be a partition of [a,b]. Let

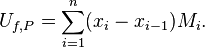

The upper Darboux sum of ƒ with respect to P is

The lower Darboux sum of ƒ with respect to P is

The lower and upper Darboux sums are sometimes called the lower and upper sums.

Darboux integrals

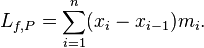

The upper Darboux integral of ƒ is

The lower Darboux integral of ƒ is

In some literature an integral symbol with an underline and overline represent the lower and upper Darboux integrals respectively.

And like Darboux sums they are sometimes simply called the lower and upper integrals.

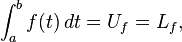

If Uƒ = Lƒ, then we call the common value the Darboux Integral.[2] We also say that ƒ is Darboux-integrable or simply integrable and set

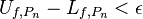

An equivalent and sometimes useful criterion for the integrability of f is to show that for every ε > 0 there exists a partition Pε on [a,b] such that[3]

Properties

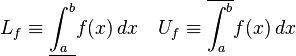

- For any given partition, the upper Darboux sum is always greater than or equal to the lower Darboux sum. Furthermore, the lower Darboux sum is bounded below by the rectangle of width (b-a) and height inf(f) taken over [a,b]. Likewise, the upper sum is bounded above by the rectangle of width (b-a) and height sup(f).

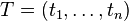

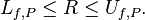

- The lower and upper Darboux integrals satisfy

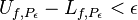

- Given any c in (a,b)

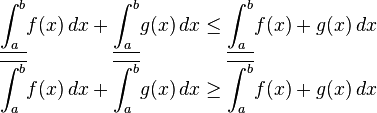

- The lower and upper Darboux integrals are not necessarily linear. Suppose that g:[a,b]→R is also a bounded function, then the upper and lower integrals satisfy the following inequalities.

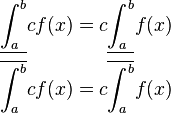

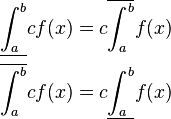

- For a constant c ≥ 0 we have

- For a constant c ≤ 0 we have

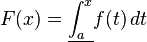

- Consider the function F:[a,b]→R defined as

then F is Lipschitz continuous. An identical result holds if F is defined using an upper Darboux integral.

Examples

A Darboux-integrable function

Suppose we want to show that the function f(x) = x is Darboux-integrable on the interval [0,1] and determine its value. To do this we partition [0,1] into n equally sized subintervals each of length 1/n. We denote a partition of n equally sized subintervals as Pn.

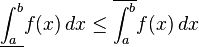

Now since f(x) = x is strictly increasing on [0,1], the infimum on any particular subinterval is given by its starting point. Likewise the supremum on any particular subinterval is given by its end point. The starting point of the kth subinterval in Pn is (k-1)/n and the end point is k/n. Thus the lower Darboux sum on a partition Pn is given by

similarly, the upper Darboux sum is given by

Since

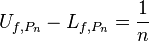

Thus for given any ε > 0, we have that any partition Pn with n > 1/ε satisfies

which shows that f is Darboux integrable. To find the value of the integral note that

An unintegrable function

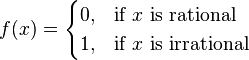

Suppose we have the function f:[0,1]→R defined as

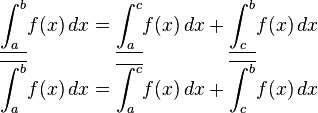

Since the rational and irrational numbers are both dense subsets of R, it follows that f takes on the value of 0 and 1 on every subinterval of any partition. Thus for any partition P we have

from which we can see that the lower and upper Darboux integrals are unequal.

Facts about the Darboux integral

A refinement of the partition

is a partition

such that for every i with

there is an integer r(i) such that

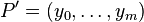

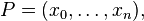

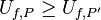

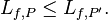

In other words, to make a refinement, cut the subintervals into smaller pieces and do not remove any existing cuts. If

is a refinement of

then

and

If P1, P2 are two partitions of the same interval (one need not be a refinement of the other), then

It follows that

Riemann sums always lie between the corresponding lower and upper Darboux sums. Formally, if

and

together make a tagged partition

(as in the definition of the Riemann integral), and if the Riemann sum of ƒ corresponding to P and T is R, then

From the previous fact, Riemann integrals are at least as strong as Darboux integrals: if the Darboux integral exists, then the upper and lower Darboux sums corresponding to a sufficiently fine partition will be close to the value of the integral, so any Riemann sum over the same partition will also be close to the value of the integral. There is a tagged partition that comes arbitrarily close to the value of the upper Darboux integral or lower Darboux integral, and consequently, if the Riemann integral exists, then the Darboux integral must exist as well.

See also

Notes

- ↑ David J. Foulis; Mustafa A. Munem (1989). After Calculus: Analysis. Dellen Publishing Company. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-02-339130-9.

- ↑ Wolfram MathWorld

- ↑ Spivak 2008, chapter 13.

References

- "Darboux Integral". Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- Darboux integral at Encyclopaedia of Mathematics

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Darboux sum", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Spivak, Michael (2008), Calculus (4 ed.), Publish or Perish, ISBN 978-0914098911

| ||||||||||||||||||

![\begin{align}

M_i = \sup_{x\in[x_{i-1},x_{i}]} f(x) , \\

m_i = \inf_{x\in[x_{i-1},x_{i}]} f(x) .

\end{align}](../I/m/85684dcca6470d3d3ce51b90a1792f67.png)

![U_f = \inf\{U_{f,P} \colon P \text{ is a partition of } [a,b]\} . \,\!](../I/m/af7030989dec193d783acbbfb17241df.png)

![L_f = \sup\{L_{f,P} \colon P \text{ is a partition of } [a,b]\} . \,\!](../I/m/e997dab8d1d70293d4de410601192360.png)

![(b-a)\inf_{x \in [a,b]} f(x) \leq L_{f,P} \leq U_{f,P} \leq (b-a)\sup_{x \in [a,b]} f(x)](../I/m/c872ef75c946de3f434338c5d9edfe55.png)

![\begin{align}

L_{f,P_n} &= \sum_{k = 1}^{n} f(x_{k-1})(x_{k} - x_{k-1})\\

&= \sum_{k = 1}^{n} \frac{k-1}{n} \cdot \frac{1}{n}\\

&= \frac{1}{n^2} \sum_{k = 1}^{n} [k-1]\\

&= \frac{1}{n^2}\left[ \frac{(n-1)n}{2} \right]

\end{align}](../I/m/a50d46fabba71f26e84bb139adaba481.png)

![\begin{align}

U_{f,P_n} &= \sum_{k = 1}^{n} f(x_{k})(x_{k} - x_{k-1})\\

&= \sum_{k = 1}^{n} \frac{k}{n} \cdot \frac{1}{n}\\

&= \frac{1}{n^2} \sum_{k = 1}^{n} k\\

&= \frac{1}{n^2}\left[ \frac{(n+1)n}{2} \right]

\end{align}](../I/m/c6ed7025d6c096121bdab62477293c1f.png)

![\begin{align}

L_{f,P} &=\sum_{k = 1}^{n}(x_{k} - x_{k-1})\inf_{x \in [x_{k-1},x_{k}]}f = 0\\

U_{f,P} &=\sum_{k = 1}^{n}(x_{k} - x_{k-1}) \sup_{x \in [x_{k-1},x_{k}]}f = 1

\end{align}](../I/m/aa729db90ae7321671c7232f5b3b87e1.png)