Damson

| Damson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ripe damsons | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Prunus |

| Subgenus: | Prunus |

| Section: | Prunus |

| Species: | P. domestica |

| Subspecies: | P. domestica subsp. insititia |

| Trinomial name | |

| Prunus domestica subsp. insititia (L.) C.K.Schneid. | |

The damson (/ˈdæmzən/) or damson plum (Prunus domestica subsp. insititia, or sometimes Prunus insititia),[1] also archaically called the "damascene"[2] is an edible drupaceous fruit, a subspecies of the plum tree. Varieties of insititia are found across Europe, but the name "damson" is derived from and most commonly applied to forms which are native to Ireland and Great Britain.[3] Damsons are relatively small plum-like fruit with a distinctive, somewhat astringent taste, and are widely used for culinary purposes, particularly in fruit preserves or Jam.

In South and Southeast Asia, the term "damson plum" sometimes refers to Jambul, the fruit from a tree in the Myrtaceae family.[4] The name "Mountain Damson" or "Bitter Damson" was also formerly applied in Jamaica to the tree Simarouba amara.[5]

History

The name damson derives from the earlier term "damascene", and ultimately from the Latin prunum damascenum, "plum of Damascus". One commonly stated theory is that damsons were first cultivated in antiquity in the area around the ancient city of Damascus, capital of modern-day Syria, and were introduced into England by the Romans. The historical link between the Roman-era damascenum and the north and west European damson is rather tenuous despite the adoption of the older name, particularly as the damascenum described by the Roman authors has more of the character of a sweet dessert plum.[6] Nevertheless, remnants of damsons are sometimes found during archaeological digs of ancient Roman camps across England, and they have clearly been cultivated, and consumed, for centuries. Damson stones have been found in the fosse at the Hungate, York, and dated to the late period of Anglo-Saxon England.[7]

The exact origin of Prunus domestica subsp. insititia is still extremely debatable: it is often thought to have arisen in wild crosses, possibly in Asia Minor, between the sloe, Prunus spinosa, and prunus cerasifera, the cherry plum.[8] Despite this, tests on cherry plums and damsons have indicated that it is possible that the damson developed directly from forms of sloe, perhaps via the round-fruited varieties known as bullaces, and that the cherry plum did not play a role in its parentage.[8] Insititia plums of various sorts, such as the German Krieche or Dutch kroosjes, occur across Europe and the word "damson" is sometimes used to refer to them in English, but many of the English varieties from which the name "damson" was originally taken have both a different typical flavour and pear-shaped (pyriform) appearance compared with continental forms.[3] Hogg commented that "the Damson seems to be a fruit peculiar to England. We do not meet with it abroad, nor is any mention of it made in any of the pomological works or nurseryman's catalogues on the Continent".[9] In addition to its fruit, the damson makes a tough hedge or windbreak, and it became the favoured hedging tree in certain parts of the country such as Shropshire and Kent.[10] As time progressed, a distinction developed between the varieties known as "damascenes" and the (usually smaller) types called "damsons", to the degree that by 1891 they were the subject of a lawsuit when a Nottinghamshire grocer complained about being supplied one when he had ordered the other.[11]

There is a body of mainly anecdotal evidence that damsons were used in the British dye and cloth manufacturing industries in the 18th and 19th centuries, with examples occurring in every major damson-growing area (Buckinghamshire, Cheshire, Westmoreland, Shropshire and Worcestershire).[12] However this may not have represented a wide-scale industry: a 2005 report for conservancy body English Nature concluded that "there seems no evidence that damsons were used extensively or techniques [for using them] developed".[13] The main use of damsons in the industrial era was in commercial jam-making, and orchards were widespread until the Second World War, after which changing tastes and the relatively high cost of British-grown fruit caused a catastrophic decline.

The damson was introduced into the American colonies by English settlers before the American Revolution. It was regarded as thriving better in the continental United States than other European plum varieties; many of the earliest references to European plums in American gardens concern the damson.[14] A favourite of early colonists, the tree has escaped from gardens and can be found growing wild in states such as Idaho.[15]

Characteristics

The main characteristic of the damson is its distinctive rich flavour; unlike other plums it is both high in sugars and highly astringent.[16] The fruit of the damson can also be identified by its shape, which is usually ovoid and slightly pointed at one end, or pyriform; its smooth-textured yellow-green flesh; and its skin, which ranges from dark blue to indigo to near-black depending on the variety (other types of Prunus domestica can have purple, yellow or red skin).[17] Most damsons are of the "clingstone" type, where the flesh adheres to the stone. The damson is broadly similar to the semi-wild bullace, also classified as ssp. insititia, which is a smaller but invariably round plum with purple or yellowish-green skin. Damsons generally have a deeply furrowed stone, unlike bullaces, and unlike prunes cannot be successfully dried.[18] Most individual damson varieties can be conclusively identified by examining the fruit's stone, which varies in shape, size and texture.

The tree blossoms with small, white flowers in early April in the Northern hemisphere and fruit is harvested from late August to September or October, depending on the cultivar.

Cultivars

Several cultivars have been selected, and some are found in both Great Britain, Ireland and the United States. There are still relatively few varieties of damson, with The Garden recording no more than "eight or nine varieties" in existence at the end of the 19th century;[19] some are self-fertile and can reproduce from seed as well as by grafting. The varieties 'Farleigh Damson'[20] and 'Prune Damson'[21] have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.

- The Farleigh Damson (syn. "Crittenden's Prolific") is named after the village of East Farleigh in Kent, where it was raised by James Crittenden in the early 19th century. An 1871 letter to the Journal of horticulture and practical gardening claimed that the original seedling had been found by a Mr. Herbert, the tenant of a market garden in Strood, who had given it to Crittenden.[22] It has small, roundish, black fruit, with a blue bloom, and is a very heavy bearer.[23] Its heavy cropping led to it being widely planted in England.

- The Shropshire Prune (syn. "Prune Damson", "Long Damson", "Damascene", "Westmoreland Damson", "Cheshire Damson") is a very old variety; its blue-purple, ovoid fruit has a distinctively "full rich astringent" flavour considered superior to other damsons, and it was thought particularly suitable for canning.[24] Hogg states that this was the variety that became specifically associated with the old name "damascene".[25] The local types often known as the "Westmoreland Damson" and "Cheshire Damson" are described as synonymous with the Shropshire Prune by the horticulturalist Harold Taylor and others.[24][26] The Shropshire was also the best-known variety of damson in the United States.[27]

- Frogmore is a variety first grown in the late 19th century in the Royal Gardens at Frogmore, described as having sweet, round-oval, purplish black fruit.[28]

- King of the Damsons (syn. "Bradley's King") is a Nottinghamshire late-season variety, making a vigorous and spreading tree with foliage that turns a distinctive yellow in autumn. It was first distributed by Bradley & Sons of Halam in around 1880. The fruit is large, obovoid and purple.[23]

- Merryweather is a popular 20th century cultivar, introduced by the firm of Henry Merryweather & Sons.[29] The fruit is deep blue and relatively sweet when ripe.

- Early Rivers, registered in 1871, was raised by Rivers' Nursery from a seed of the variety St Etienne, and has roundish blue-black fruit with a chalky bloom.[30]

- The Blue Violet originated in Westmoreland (possibly as a hybrid of the Shropshire Prune) and was first sent to the National Fruit Trials in the 1930s.[31] An early variety, fruiting in August, it was long thought to have been lost but a few trees were discovered in the Lake District in 2007.[32]

- The Common Damson (syn. "Small Round Damson") was a traditional variety with small, black fruit, being probably very close to wild specimens. It had a mealy texture and acid flavour, and by the 1940s it was no longer planted.[33]

A type of damson once widely grown in County Armagh, Ireland, was never definitely identified but generally known as the "Armagh Damson"; its fruit were particularly well regarded for canning.[34] Local types of English prune such as the "Aylesbury Prune", or the Gloucestershire "Old Pruin", are sometimes described as damson varieties.

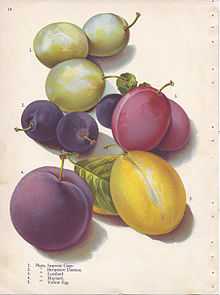

White damson

Although the majority of damson varieties are blue-black or purple in colour, there are at least two now-rare forms of "white damson", both having green or yellow-green skin. The National Fruit Collection has accessions of the "White Damson (Sergeant)"[35] and the larger "White Damson (Taylor)",[36] both of which may first have been mentioned in the 1620s.

To confuse matters, the White Bullace was in the past sold in London markets under the name of "white damson".[37] Bullaces can usually be distinguished from damsons by their spherical shape, relatively smooth stones, and poorer flavour, and generally ripen up to a month later in the year than damsons.

Uses

The skin of the damson can have a very tart flavour, particularly when unripe (the term "damson" is often used to describe red wines with rich yet acidic plummy flavours). The fruit is therefore most often used for cooking, and is commercially grown for preparation in jam and other fruit preserves. Some varieties of damson, however, such as "Merryweather", are sweet enough to eat directly from the tree, and most are palatable raw if allowed to fully ripen. They can also be pickled, canned, or otherwise preserved. The Luxembourg speciality quetschentaart is a fruit pie made with insititia plums.[38]

Because damson stones or seeds are difficult to separate from the flesh, preserves are often made from whole fruit. Some cooks then remove the stones, but others, either in order not to lose any of the pulp or because they believe the flavor is better, leave the seeds in the final product. In addition to using damson preserves as one uses any jam, some people serve it with roasted or braised meat dishes just as they might serve cranberry sauce with roasted fowl.

Damson gin is made in a similar manner to sloe gin, although less sugar is necessary as the damsons are sweeter than sloes. Insititia varieties similar to damsons are used to make slivovitz, a distilled plum spirit made in Slavic countries.[39] Damson wine was once common in England: a 19th-century reference said that "good damson wine is, perhaps, the nearest approach to good port that we have in England. No currant wine can equal it."[40]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prunus domestica subsp. insititia. |

- ↑ M. H. Porcher "Sorting ''Prunus'' names, in "Multilingual multiscript plant names database, University of Melbourne. Plantnames.unimelb.edu.au. Retrieved on 2012-01-01.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson equates "damascene" and "damson" and for "damask plum" simply states "see Plum" (A Dictionary of the English Language, 1755, p.532). Later expanded editions also distinguish between "damascene" and "damson", the latter being described as "smaller and [with] a peculiar bitter or roughness".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Woldring, H. "On the origin of plums: a study of sloe, damson, cherry plums, domestic plums and their intermediate forms", in Palaeohistoria, 39,40 (1997-1998): Institute of Archaeology, Groningen, 538

- ↑ "Jambolan". Purdue University. 2006.

- ↑ Bowerbank, "The Commercial Quassia, or Bitterwood", The Technologist, II (1862), 251

- ↑ Dalby, A. Food in the Ancient World,, Routledge, 2003, p.264

- ↑ Godwin, Sir H. The History of the British Flora, Cambridge University Press, 1984, p.197

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Woldring, 1997, 535

- ↑ Hogg, R. The fruit manual: a guide to the fruits and fruit trees of Great Britain, 1884, p.695

- ↑ The Common Ground book of orchards: conservation, culture and community, Common Ground, 2000, p.32

- ↑ Ayto, J. The Glutton's Glossary: A Dictionary of Food and Drink Terms, Routledge, 1990, p.94

- ↑ Stephens, B. "Damsons & Dyeing" (report for English Nature), 2005, in Wyre Forest Study Group Review, 2006, 52

- ↑ Stephens, 2005, p.53

- ↑ Hatch, P. The Fruits and Fruit Trees of Monticello, University of Virginia Press, 1998, p.108

- ↑ Johnson, F. D. Wild trees of Idaho, UIP, 1995, p.78

- ↑ Greenoak, F. Forgotten fruit: the English orchard and fruit garden, A. Deutsch, 1983, p.77

- ↑ D. G. Hessayon (1991) The fruit expert. Expert Books. ISBN 0-903505-31-2. Retrieved on 2012-01-01.

- ↑ Woldring, 1997, 548

- ↑ The Garden, v.49 (1896), 432

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector - Prunus insititia 'Farleigh Damson'". Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "RHS Plant Selector - Prunus insititia 'Prune Damson'". Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Letter from Thomas Rivers, Journal of horticulture and practical gardening, Volume 20, (1871), 349

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Hyams and Jackson, The orchard and fruit garden: a new pomona of hardy and sub-tropical fruits, Longmans, 1961, p.48

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Taylor, H. V. The plums of England, Lockwood, 1949, p.71

- ↑ Hogg, 1884, p.250

- ↑ Fraser, H. in Gardeners' chronicle, vol. 148 (1960), 97

- ↑ Kains, M. Home Fruit Grower, 1918, p.175

- ↑ Hedrick, U. Cyclopedia of Hardy Fruits, Macmillan, 1922, p.199

- ↑ Macself, A. J. The fruit garden, C Scribner's Sons, 1926, p.113

- ↑ Plums Gages and Cherries, East of England Orchards Project

- ↑ MacCarthy, D. British food facts & figures, 1986: a comprehensive guide to British agricultural and horticultural produce, British Farm Produce Council, 1986, p.151

- ↑ The Garden, v.132, Royal Horticultural Society, 711

- ↑ Taylor, 1949, p.114

- ↑ The fruit year book, 4 (1950), Royal Horticultural Society, p.44

- ↑ White Damson (Sergeant), National Fruit Collection, accessed 05-09-12

- ↑ White Damson (Taylor), National Fruit Collection, accessed 05-09-12

- ↑ Grindon, L.H. Fruits and Fruit-Trees, Home and Foreign. an Index to the Kinds Valued in Britain, 1885, p.71

- ↑ "Quetschentaart", Delhaize Food. (French) Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ↑ P. SATORA and T. TUSZYNSKI (2005). "Biodiversity of Yeasts During Plum Fermentation" (PDF). Food Technol. Biotechnol. 43 (3): 277–282.

- ↑ "Damson Wine", in Hogg and Johnson (eds) The Journal of Horticulture, Cottage Gardener, and Country Gentleman, v.III NS (1862), 264