Dalmatian language

| Dalmatian | |

|---|---|

| langa Dalmata | |

| Native to | Croatia, Montenegro |

| Region | Adriatic coast |

| Extinct | 10 June 1898, when Tuone Udaina was killed |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

dlm |

Linguist list |

dlm |

| Glottolog |

dalm1243[1] |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAA-t |

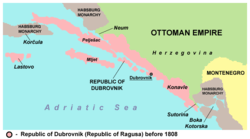

Dalmatian /dælˈmeɪʃⁱən/[2][3] or Dalmatic /dælˈmætɪk/[2] was a Romance language spoken in the Dalmatia region of Croatia, and as far south as Kotor in Montenegro. The name refers to a pre-Roman tribe of the Illyrian linguistic group, Dalmatae. The Ragusan dialect of Dalmatian was the official language of the Republic of Ragusa, though in later times Venetian (representing the Romance language population) or Serbo-Croatian (for the Slavophone population) came to supersede it.

Dalmatian speakers lived in the coastal towns Zadar (Jadera), Trogir (Tragur), Spalato (Split; Spalatro), Ragusa (Dubrovnik; Raugia), and Kotor (Cattaro), each of these cities having a local dialect, and on the islands of Krk (Vikla), Cres (Crepsa) and Rab (Arba).

Dialects

Almost every city developed its own dialect. Most of these became extinct before they were recorded, so the only trace of these ancient dialects is some words borrowed into local dialects of today's Croatia.

Ragusan dialect

Ragusan is the Southern dialect, whose name is derived from the Romance name of Dubrovnik, Ragusa. It came to the attention of modern scholars in two letters, from 1325 and 1397, and other mediaeval texts, which show a language influenced heavily by Venetian. The available sources include some 260 Ragusan words including pen ("bread"), teta ("father"), chesa ("house"), and fachir ("to do"), which were quoted by the Dalmatian Filippo Diversi, the rector of Ragusa in the 1430s.

The Maritime Republic of Ragusa had, at one time, an important fleet, but its influence decreased over time, to the point that, by the 15th century, it had been reduced to only about 300 ships.[4] The language was in trouble in the face of Slav expansion, as the Ragusan Senate decided that all debates had to be held in lingua veteri ragusea (ancient Ragusan language) and the use of the Slav was forbidden. Nevertheless, in the 16th century, Ragusan fell out of use and almost extinct.

Vegliot dialect

Vegliot (the native name being Viklasun)[5] is the Northern dialect. The language's name is derived from the Italian name of Krk, Veglia, an island in Kvarner, called Vikla in Vegliot. On the inscription dating from the beginning of the fourth century, Krk is named as Splendissima civitas Curictarum. The Serbo-Croatian name derives from the Roman name (Curicum, Curicta), whereas the younger title Vecla, Vegla, Veglia (meaning "Old Town") was created in the mediaeval Romanesque period.

History

The Roman Republic gradually came to occupy the territory of Illyria between 229 and 155 BC. Merchants and authorities settling from Rome brought with them the Latin language, and eventually the indigenous inhabitants mostly abandoned their languages (prevalently a variety of Illyrian tongues) for Vulgar Latin. After the Roman capital moved to Constantinople, Greek began to replace Latin as the Lingua Franca in the empire (eventually becoming official in 620), but Illyrian towns continued to speak Latin (see Illyro-Roman), which evolved over time into regional dialects and eventually into distinct Romance languages.

Dalmatian was spoken on the Dalmatian coast from Fiume (now Rijeka) as far south as Cottora (Kotor) in Montenegro. Speakers lived mainly in the coastal towns of Jadera (Zadar), Tragurium (Trogir), Spalatum[6] (Split), Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and Acruvium (Kotor), and also on the islands of Curicta (Krk), Crepsa (Cres) and Arba (Rab). Almost every city developed its own dialect, but the most important dialects we know of were Vegliot, a northern dialect spoken on the island of Curicta, and Ragusan, a southern dialect spoken in and around Ragusa (Dubrovnik).

The Dalmatian dialect of Ragusa is known from two letters, dated 1325 and 1397, as well as from other mediaeval texts. The oldest preserved documents written in Dalmatian are 13th century inventories in Ragusan. The available sources include roughly 260 Ragusan words. Surviving words include pen ("bread"), teta ("father"), chesa ("house"), and fachir ("to do"), which were quoted by the Dalmatian, Filippo Diversi, the head of school of Ragusa in the 1430s. The earliest reference to the Dalmatian language dates from the tenth century and it is estimated that about 50,000 people spoke it at that time, though the main source of this information, the Italian linguist Matteo Bartoli, may have exaggerated his figures.

Dalmatian was influenced particularly heavily by Venetian and Serbo-Croatian (despite the latter, the Latin roots of Dalmatian remained prominent). A 14th-century letter from Zadar (origin of the Iadera dialect) shows strong influence from Venetian, the language that after years under Venetian rule superseded Iadera and other dialects of Dalmatian. Other dialects met their demise with the settlement of populations of Slavic speakers.

The last speaker of any Dalmatian dialect was Burbur Tuone Udaina (Italian: Antonio Udina), who was accidentally killed in an explosion on June 10, 1898.[7][8] His language was studied by the scholar Matteo Bartoli, himself a native of nearby Istria, who visited him in 1897 and wrote down approximately 2,800 words, stories, and accounts of his life, which were published in a book that has provided much information on the vocabulary, phonology, and grammar of the language. Bartoli wrote in Italian and published a translation in German (Das Dalmatische) in 1906. The Italian language manuscripts were reportedly lost, and the work was not re-translated into Italian until 2001.

Characteristics

Once thought to be a language that bridged the gap between the Romanian language and Italian, it was only distantly related to the nearby Romanian dialects, such as the nearly extinct Istro-Romanian, spoken in nearby Istria, Croatia.

Some of its features are quite archaic. Dalmatian is the only Romance language that palatalised /k/ and /g/ before /i/, but not before /e/ (others palatalise in both situations, except Sardinian, which did not palatalise): Latin: civitate > Vegliot: cituot ("city"), Latin: cenare > Vegliot: kenur ("to dine").

Some of its words have been preserved as borrowings in South Slavic languages, mainly in the Chakavian dialect of Serbo-Croatian.

Similarities to Romanian

Among the similarities with Romanian, some consonant shifts can be found among the Romance languages only in Dalmatian and Romanian:

| Source | Destination | Latin | Vegliot | Romanian | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /kt/ | /pt/ | octo | guapto | opt | otto | eight |

| /ŋn/ | /mn/ | cognatus | comnut | cumnat | cognato | brother-in-law |

| /ks/ | /ps/ | coxa | copsa | coapsă | coscia | thigh |

Vocabulary

Dalmatian kept Latin words related to urban life, lost (or if preserved, not with the original sense) in Romanian, such as cituot "city" (in Romanian cetate means "fort", not "city"; compare also Albanian qytet, borrowed from Latin, which, too, means "fort", besides "city"). The Dalmatians retained an active urban society in their city-states, whereas most Romanians were driven into small mountain settlements during the Great Migrations of 400 to 800 AD.[9]

Venetian became a major influence on the language as Venetian commercial influence grew. The Chakavian dialect and Dubrovnik Shtokavian dialect, which was spoken outside the cities since the immigration of the Slavs, gained importance in the cities by the 16th century, and it eventually replaced Dalmatian as a day-to-day language.

Grammar

An analytic trend can be observed in Dalmatian: nouns and adjectives began to lose their gender and number inflexions, the noun declension disappeared completely, and the verb conjugations began to follow the same path; but the verb maintained a person and number distinction, except in the third person (in common with Romanian and several dialects of Italy).

The definite article precedes the noun, unlike the Eastern Romance languages (like Romanian and except the South Italian dialects), which have it postposed to the noun.

Language sample

The following are examples of the Lord's Prayer in Latin, Dalmatian, Serbo-Croatian, Friulian, Italian, Istro-Romanian and Romanian:

| Latin | Dalmatian | Serbo-Croatian | Friulian | Italian | Istro-Romanian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pater noster, qui es in caelis, | Tuota nuester, che te sante intel sil, | Oče naš, koji jesi na nebesima, | Pari nestri, che tu sês in cîl, | Padre nostro, che sei nei cieli, | Ciace nostru car le ști en cer, | Tatăl nostru carele ești în ceruri, | Our Father, who art in heaven, |

| sanctificetur Nomen Tuum. | sait santificuot el naun to. | sveti se ime tvoje. | che al sedi santifiât il to nom. | sia santificato il tuo nome. | neca se sveta nomelu teu. | sfințească-se numele tău. | hallowed be thy name. |

| Adveniat Regnum Tuum. | Vigna el raigno to. | Dođi kraljevstvo tvoje. | Che al vegni il to ream. | Venga il tuo regno. | Neca venire craliestvo to. | Vie împărăția ta. | Thy kingdom come. |

| Fiat voluntas Tua, sicut in caelo, et in terra. | Sait fuot la voluntuot toa, coisa in sil, coisa in tiara. | Budi volja tvoja, kako na nebu tako i na zemlji. | Che e sedi fate la tô volontât sicu in cîl cussì ancje in tiere. | Sia fatta la tua volontà, come in cielo così in terra. | Neca fie volia ta, cum en cer, așa și pre pemânt. | Facă-se voia ta, precum în cer, așa și pe pământ. | Thy will be done, on Earth as it is in heaven. |

| Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie. | Duote costa dai el pun nuester cotidiun. | Kruh naš svagdajni daj nam danas. | Danus vuê il nestri pan cotidian. | Dacci oggi il nostro pane quotidiano. | Pera nostre saca zi de nam astez. | Pâinea noastră cea de toate zilele, dă-ne-o nouă astăzi. | Give us this day our daily bread. |

| Et dimitte nobis debita nostra, | E remetiaj le nuestre debete, | I odpusti nam duge naše, | E pardoninus i nestris debits, | E rimetti a noi i nostri debiti, | Odproste nam dutzan, | Și ne iartă nouă păcatele noastre, | And forgive us our trespasses, |

| Sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. | Coisa nojiltri remetiaime a i nuestri debetuar. | Kako i mi otpuštamo dužnicima našim. | Sicu ancje nô ur ai pardonìn ai nestris debitôrs. | Come noi li rimettiamo ai nostri debitori. | Ca și noi odprostim a lu nostri dutznici. | Precum și noi le iertăm greșiților noștri. | As we forgive those who trespass against us. |

| Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, | E naun ne menur in tentatiaun, | I ne uvedi nas u napast, | E no stâ menânus in tentazion, | E non ci indurre in tentazione, | Neca nu na tu vezi en napastovanie, | Și nu ne duce pe noi în ispită, | And lead us not into temptation, |

| sed libera nos a Malo. | miu deleberiajne dal mal. | nego izbavi nas od zla. | ma liberinus dal mâl. | ma liberaci dal male. | neca na zbăvește de zvaca slabe. | ci ne izbăvește de cel rău. | but deliver us from evil. |

| Amen! | Amen! | Amen! | Amen! | Amen! | Amen! | Amin! | Amen! |

Parable of the Prodigal Son

- Dalmatian: E el daic: Jon ciairt jomno ci avaja doi feil, e el plé pedlo de louro daic a soa tuota: Tuota duoteme la puarte de moi luc, che me toca, e jul spartait tra louro la sostuanza e dapù pauch dai, mais toich indajoi el feil ple pedlo andait a la luorga, e luoc el dissipuat toich el soo, viviand malamiant. Muà el ju venait in se stiass, daic: quinci jomni de journata Cn cuassa da me tuota i ju bonduanza de puan e cua ju muor de fum.

- English: And He said: There was a man who had two sons, and the younger of them said to his father: "Father give me the share of his property that will belong to me." So he divided the property between them. A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and travelled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. But when he came to himself he said: "How many of my father's hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger."

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Dalmatian". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ↑ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521152532

- ↑ Notizie Istorico-Critiche Sulla Antichita, Storia, e Letteratura de' Ragusei, Francesco Maria Appendini, 1803.

- ↑ Bartoli, 2000

- ↑ Colloquia Maruliana, Vol. 12 Travanj 2003. Zarko Muljacic — On the Dalmato-Romance in Marulić's Works (hrcak.srce.hr). Split Romance (Spalatin) are extant by the author. Zarko Muljacic has set off in the only way possible, the indirect way of attempting to trace the secrets of its historical phonology by analysing any lexemes of possible Dalmato-Romance origin that have been preserved in Marulić's Croatian works.

- ↑ Eugeen Roegiest (2006). Vers les sources des langues romanes: un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania. ACCO. p. 138. ISBN 90-334-6094-7.

- ↑ William B Brahms (2005). Notable Last Facts: A Compendium of Endings, Conclusions, Terminations and Final Events throughout History. Original from the University of Michigan: Reference Desk Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-9765325-0-7.

- ↑ Florin Curta (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge medieval textbooks. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

Notations

- Bartoli, Matteo Giulio. (1906). Das Dalmatische (2 vols), Vienna: Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften,

- Bartoli, Matteo Giulio. (2000). Il Dalmatico (translation from the German original). In Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. Italy

- Fisher, John. (1975). Lexical Affiliations of Vegliote. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-7796-7.

- Hadlich, Roger L. (1965). The phonological history of Vegliote, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press

- Price, Glanville. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-22039-9.

- Ive, Antonio. L' Antico dialetto di Veglia.

External links

| Dalmatian language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dalmatian language. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||