Dakshina

Dakshina (Sanskrit: dakṣiṇa, means "south, southern",[1] but also refers to a Tantric concept right-hand path,[2] as well as a Vedic concept of donation or payment for the services of a priest, spiritual guide or teacher.[3]

Etymology and description

As a Vedic concept, the donation originally consisted of a cow (according to Kātyāyana Śrautasūtra 15, Lāṭyāyana Śrautasūtra 8.1.2). The term itself is derived from this, the feminine dakṣiṇā being a term for a cow able to calve and give milk (a prolific cow, milch-cow) in the Rigveda.

Dakshina is personified as a goddess along with Brahmanaspati, Indra and Soma in RV 1.18.5 and RV 10.103.8, and is the reputed author of RV 10.107 according to the Anukramani.

In later literature, in the Manusmrti and in the Ramayana, the term dakshina acquires a more general meaning of "thanks" or "a gift".

Gurudakshina

Gurudakshina refers to the tradition of repaying one's teacher or guru after a period of study or the completion of formal education, or to spiritual guide.[4] This tradition is one of acknowledgment, respect, and thanks.[5] It is a form of reciprocity and exchange between student and teacher. The repayment is not exclusively monetary and may be a special task the teacher wants the student to accomplish.

Dakshina in Indian epics

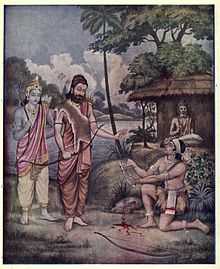

There is a symbolic story in the Indian epic Mahabharata that discusses proper and improper gurudakshina, after a character named Ekalavya.[6] This socio-mythological story refers to a tribal boy's passion to learn and master archery.

Ekalavya, eager to learn archery, approaches Dronacharya - the best teacher in the land. Drona asks Ekalavya why he wants to learn archery. Ekalavya replies that he wants to protect and rescue defenseless animals such as deer and fawns from cruel wolves.[7] Drona is moved by Ekalavya's noble cause and lack of competitive ego, but refuses to teach Ekalavya claiming he is too busy to take students, but in reality does not want to teach a student from a non-warrior family and wants to avoid creating competition for Arjuna. Dejected but unwilling to give up, Ekalavya returns to the forest and builds a statue of Drona for inspiration, and then teaches himself the art of archery. With practice, over time, Ekalavya becomes the finest archer in the land. Years later, in a forest Drona and his students witness a feat of archery none of the formal students of Drona knew, stunning everyone. They trace the source, and find the feat as an achievement of Ekalavya. Drona approaches Ekalavya and asks who taught him archery. Ekalavya says you, Drona through your statue. Drona asks him if Ekalavya would pay gurudakshina. Ekalavya replies yes. Drona asks for Ekalavya's right thumb, which Ekalavya promptly cuts and presents to Drona. This dakshina cripples Ekalavya.[8][9]

The story, like many stories in Mahabharata is an open ended parable on education, personal drive to learn, and what is proper and improper dakshina? In the epic Mahabharata, after the right hand thumb as gurudakshina event, Drona is haunted and wonders if demanding Ekalavya's thumb was proper,[10] Ekalavya goes on to re-master archery with four fingers of his right hand, as well as left hand, thereby becoming a mighty warrior, becomes accepted as a king, and tells his children that education is for everyone and that no one can close the doors of education on any human being.[11][12]

See also

References

- ↑ See entry for South, English-Sanskrit Dictionary, Spoken Sanskrit, Germany (2010)

- ↑ Bhattacharya, N. N. History of the Tantric Religion. Second Revised Edition. Manohar Publications, Delhi, 1999. ISBN 81-7304-025-7

- ↑ dakSiNa Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Cologne, Germany (2006)

- ↑ गुरुदक्षिणा, Gurudakshina English-Sanskrit Dictionary, Spoken Sanskrit, Germany (2010)

- ↑ Radhakrishnan, L. J., & Rabb, H. (2010). Even in nephrology, gurudakshina is important, Kidney International, 78, 3-5

- ↑ Kakar, S. (1971). The Theme of Authority in Sociaal Relation in India. The Journal of Social Psychology, 84(1), 93-101

- ↑ Kailasam, T. P. (2007). Little Lays and Plays Pages from the Epic. Musings On Indian Writing In English, Vol. 3: Drama, 3, 40, Editor: N Sharda Iyer, ISBN 978-8176258012

- ↑ Shankar, S. (1994). The thumb of Ekalavya: Postcolonial studies and the" Third World" scholar in a neocolonial world. World Literature Today, 68(3), 479-487

- ↑ Nachimuthu, P. (2006). Mentors in Indian mythology. Management and Labour Studies, 31(2), 137-151

- ↑ Kumar, S. THE MAHABHARATA. HarperCollins Publishers India (2011), ISBN 978-93-5029-191-7

- ↑ Brodbeck, S. (2006). Ekalavya and Mahābhārata 1.121–28, International Journal of Hindu Studies, 10(1), 1-34

- ↑ Brodbeck, Simon (2004) 'The story of Ekalavya in the Mahabharata.' In: Leslie, J. and Clark, M., (eds.), Text, belief and personal identity: creating a dialogue, ISBN 9780728603639