Dabigatran

| |

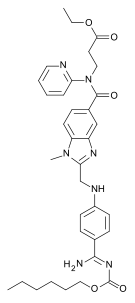

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

| Ethyl N-[(2-{[(4-{N '-[(hexyloxy)carbonyl]carbamimidoyl}phenyl)amino]methyl}-1-methyl-1H-benzimidazol-5-yl)carbonyl]-N-2-pyridinyl-β-alaninate | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Pradaxa, Pradax, Prazaxa |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| |

| |

| oral | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 3–7%[1] |

| Protein binding | 35%[1] |

| Half-life | 12–17 hours[1] |

| Identifiers | |

|

211915-06-9 | |

| B01AE07 | |

| PubChem | CID 6445226 |

| DrugBank |

DB06695 |

| ChemSpider |

4948999 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL539697 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C34H41N7O5 |

| 627.734 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Dabigatran (Pradaxa in Australia, Canada, Europe and USA, Prazaxa in Japan) is an oral anticoagulant from the class of the direct thrombin inhibitors. It is being studied for various clinical indications and in some cases it offers an alternative to warfarin as the preferred orally administered anticoagulant ("blood thinner") since it does not require blood tests for international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring while offering similar results in terms of efficacy. There is no specific way to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in the event of a major bleeding event,[2][3] unlike warfarin,[4] although a potential dabigatran antidote (pINN: idarucizumab) is undergoing clinical studies.[5] It was developed by the pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim.

Medical uses

Dabigatran is used to prevent strokes in those with atrial fibrillation (afib) due to non heart valve causes, as well as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in persons who have been treated for 5–10 days with parenteral anticoagulant (usually low molecular weight heparin), and to prevent DVT and PE in some circumstances.[6]

It appears to be as good as warfarin in preventing nonhemorrhagic strokes and embolic events in those with afib not due to valve problems.[7]

Contraindications

Dabigatran is contraindicated in patients who have active pathological bleeding since dabigatran can increase bleeding risk and can also cause serious and potentially life-threatening bleeds.[8] Dabigatran is also contraindicated in patients who have a history of serious hypersensitivity reaction to dabigatran (e.g. anaphylaxis or anaphylactic shock).[8] The use of dabigatran should also be avoided in patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valve due to the increased risk of thromboembolic events (e.g. valve thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction) and major bleeding associated with dabigatran in this population.[8][9][10]

Adverse effects

The most commonly reported side effect of dabigatran is GI upset. When compared to people anticoagulated with warfarin, patients taking dabigatran had fewer life-threatening bleeds, fewer minor and major bleeds, including intracranial bleeds, but the rate of GI bleeding was significantly higher. Dabigatran capsules contain tartaric acid, which lowers the gastric pH and is required for adequate absorption. The lower pH has previously been associated with dyspepsia; some hypothesize that this plays a role in the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.[11]

A small but significantly increased risk of myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) has been noted when combining the safety outcome data from multiple trials.[12]

Reduced doses should be used in renal impairment.

Pharmacokinetics

Dabigatran has a half-life of approximately 12-14 h and exert a maximum anticoagulation effect within 2-3 h after ingestion.[13] Fatty foods delay the absorption of dabigatran, although the bio-availability of the drug is unaffected.[1] One study showed that absorption may be moderately decreased if taken with a proton pump inhibitor.[14] Drug excretion through P-glycoprotein pumps is slowed in patients taking strong p-glycoprotein pump inhibitors such as quinidine, verapamil, and amiodarone, thus raising plasma levels of dabigatran.[15]

History

Dabigatran (then compound BIBR 953) was discovered from a panel of chemicals with similar structure to benzamidine-based thrombin inhibitor α-NAPAP (N-alpha-(2-naphthylsulfonylglycyl)-4-amidinophenylalanine piperidide), which had been known since the 1980s as a powerful inhibitor of various serine proteases, specifically thrombin, but also trypsin. Addition of ethyl ester and hexyloxycarbonyl carbamide hydrophobic side chains led to the orally absorbed prodrug, BIBR 1048 (dabigatran etexilate).[16]

On March 18, 2008, the European Medicines Agency granted marketing authorisation for Pradaxa for the prevention of thromboembolic disease following hip or knee replacement surgery and for non-valvular atrial fibrillation.[17]

The National Health Service in Britain authorised the use of dabigatran for use in preventing blood clots in hip and knee surgery patients. According to a BBC article in 2008, Dabigatran was expected to cost the NHS £4.20 per day, which was similar to several other anticoagulants,.[18]

Pradax received a Notice of Compliance (NOC) from Health Canada on June 10, 2008,[19] for the prevention of blood clots in patients who have undergone total hip or total knee replacement surgery. Approval for atrial fibrillation patients at risk of stroke came in October 2010.[20][21]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Pradaxa on October 19, 2010, for prevention of stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.[22][23][24][25] The approval came after an advisory committee recommended the drug for approval on September 20, 2010[26] although caution is still urged by some outside experts.[27]

On February 14, 2011, the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association added dabigatran to their guidelines for management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation with a class I recommendation.[28]

In May 2014 the FDA reported the results of a large study comparing dabigatran to warfarin in 134,000 Medicare patients. The Agency concluded that dabigatran is associated with a lower risk of overall mortality, ischemic stroke, and bleeding in the brain than warfarin. Gastrointestinal bleeding was more common in those treated with dabigatran than in those treated with warfarin. The risk of heart attack was similar between the two drugs. The Agency reiterated its opinion that dabigatran's overall risk/benefit ratio is favorable.[29]

On July 26, 2014, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) published a series of investigations that accused Boehringer of withholding critical information about the need for monitoring to protect patients from severe bleeding, particularly in the elderly. Review of internal communications between Boehringer researchers and employees, the FDA and the EMA revealed that Boehringer researchers found evidence that serum levels of dabigatran vary widely. The BMJ investigation suggested that Boehringer had a financial motive to withhold this concern from regulatory health agencies because the data conflicted with their extensive marketing of dabigatran as an anticoagulant that does not require monitoring. [30] [31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Pradaxa Full Prescribing Information. Boehringer Ingelheim. October 2010.

- ↑ Eerenberg, ES; Kamphuisen, PW; Sijpkens, MK; Meijers, JC; Buller, HR; Levi, M (2011-10-04). "Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects". Circulation 124 (14): 1573–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029017. PMID 21900088. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ↑ van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, Liesenfeld KH, Wienen W, Feuring M, Clemens A (Department of Drug Discovery Support, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma) (Jun 2010). "Dabigatran etexilate--a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity". Thrombosis and Haemostasis 103 (6): 1116–27. doi:10.1160/TH09-11-0758. PMID 20352166. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

Although there is no specific antidote to antagonise the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, due to its short duration of effect drug discontinuation is usually sufficient to reverse any excessive anticoagulant activity.

- ↑ Hanley JP, J P (Nov 2004). "Warfarin reversal". Journal of Clinical Pathology 57 (11): 1132–9. doi:10.1136/jcp.2003.008904. PMC 1770479. PMID 15509671.

- ↑ "Boehringer Ingelheim’s Investigational Antidote for Pradaxa® (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) Receives FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation" (Press release). Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim’. 2014-06-26. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ http://www.drugs.com/pro/pradaxa.html Pradaxa

- ↑ Gómez-Outes, A; Terleira-Fernández, AI; Calvo-Rojas, G; Suárez-Gea, ML; Vargas-Castrillón, E (2013). "Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, or Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Subgroups.". Thrombosis 2013: 640723. PMID 24455237.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) Prescribing Information: http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=ba74e3cd-b06f-4145-b284-5fd6b84ff3c9#Section_5.4, accessed October 29, 2014.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate mesylate) should not be used in patients with mechanical prosthetic heart valves". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ↑ Eikelboom, JW; Connolly, SJ; Brueckmann, M et al. (September 2013). "Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves". N Engl J Med 369: 1206–1214. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300615. PMID 23991661.

- ↑ ML Blommel et al. (2011). "Dabigatran etexilate: A novel oral direct thrombin inhibitor". Am J Health Syst Pharm 68 (16): 1506–19. doi:10.2146/ajhp100348. PMID 21817082.

- ↑ Uchino K, Hernandez AV; Hernandez (2012). "Dabigatran associated with higher risk of acute coronary events - meta-analysis of noninferiority randomized controlled trials". Arch. Intern. Med. Online first (5): 397–402. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1666. PMID 22231617.

- ↑ Chongnarungsin D; Ratanapo S; Srivali N; Ungprasert P; Suksaranjit P; Ahmed S; Cheungpasitporn W (2012). "In-Depth Review of Stroke Prevention in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation". Am. Med. J. 3 (2): 100. doi:10.3844/amjsp.2012.100.103.

- ↑ Stangier J, Eriksson BI, Dahl OE et al. (May 2005). "Pharmacokinetic profile of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate in healthy volunteers and patients undergoing total hip replacement". J Clin Pharmacol 45 (5): 555–63. doi:10.1177/0091270005274550. PMID 15831779.

- ↑ "Pradaxa Summary of Product Characteristics". European Medicines Agency.

- ↑ Hauel NH, Nar H, Priepke H, Ries U, Stassen JM, Wienen W; Nar; Priepke; Ries; Stassen; Wienen (April 2002). "Structure-based design of novel potent nonpeptide thrombin inhibitors". J Med Chem 45 (9): 1757–66. doi:10.1021/jm0109513. PMID 11960487. Lay summary.

- ↑ "Pradaxa EPAR". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ↑ "Clot drug 'could save thousands'". BBC News Online. 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD): Pradax" Health Canada. 2008-11-06.

- ↑ Kirkey, Sharon (29 October 2010). "Approval of new drug heralds 'momentous' advance in stroke prevention". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ↑ "Pradax (Dabigatran Etexilate) Gains Approval In Canada For Stroke Prevention In Atrial Fibrillation" Medical News Today. 28 October 2010.

- ↑ Connolly, SJ; Ezekowitz, MD; Yusuf, S et al. (September 2009). "Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation" (PDF). N Engl J Med 361 (12): 1139–51. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. PMID 19717844.

- ↑ Turpie AG (January 2008). "New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation". Eur Heart J 29 (2): 155–65. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm575. PMID 18096568.

- ↑ "Boehringer wins first US OK in blood-thinner race". Thomson Reuters. 2010-10-19. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ↑ "FDA approves Pradaxa to prevent stroke in people with atrial fibrillation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2010-10-19.

- ↑ Shirley S. Wang (2010-09-20). "New Blood-Thinner Recommended by FDA Panel". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ↑ Merli G, Spyropoulos AC, Caprini JA; Spyropoulos; Caprini (August 2009). "Use of emerging oral anticoagulants in clinical practice: translating results from clinical trials to orthopedic and general surgical patient populations". Ann Surg 250 (2): 219–28. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ae6dbe. PMID 19638915.

- ↑ Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, Ezekowitz MD, Jackman WM, January CT, Lowe JE, Page RL, Slotwiner DJ, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM, Jacobs AK; Curtis; Ellenbogen; Estes Na; Ezekowitz; Jackman; January; Lowe; Page; Slotwiner; Stevenson; Tracy; Fuster; Rydén; Cannom; Crijns; Curtis; Ellenbogen; Halperin; Kay; Le Heuzey; Lowe; Olsson; Prystowsky; Tamargo; Wann; Jacobs; Anderson; Albert et al. (March 2011). "2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS Focused Update on the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (Update on Dabigatran): A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation 123 (10): 1144–50. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820f14c0. PMID 21321155.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA study of Medicare patients finds risks lower for stroke and death but higher for gastrointestinal bleeding with Pradaxa (dabigatran) compared to warfarin".

- ↑ Cohen, D (July 2014). "Dabigatran: how the drug company withheld important analyses". BMJ 349: g4670. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4670. PMID 25055829.

- ↑ Moore TJ, Cohen MR, Mattison DR; Cohen; Mattison (July 2014). "Dabigatran, bleeding, and the regulators". BMJ 349: g4517. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4517. PMID 25056265.

External links

- Pradaxa.com. Boehringer Ingelheim.

- dabigatran.com. Boehringer Ingelheim.

- Pradaxa For U.S. Health Care Professionals. Boehringer Ingelheim.

- Pradaxa Prescribing Information. Boehringer Ingelheim.

- Pradaxa Medication Guide. Boehringer Ingelheim.

- Dabigatran. MedlinePlus. United States National Library of Medicine (NLM).

- Dabigatran. Drug Information Portal. United States National Library of Medicine (NLM).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||