DEET

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

N,N-Diethyl-3-methylbenzamide | |

| Other names

N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide | |

| Identifiers | |

| ATC code | P03 QP53GX01 |

| 134-62-3 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:7071 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1453317 |

| ChemSpider | 4133 |

| |

| Jmol-3D images | Image |

| KEGG | D02379 |

| PubChem | 4284 |

| |

| UNII | FB0C1XZV4Y |

| Properties | |

| C12H17NO | |

| Molar mass | 191.27 g/mol |

| Density | 0.998 g/mL |

| Melting point | −33 °C (−27 °F; 240 K) |

| Boiling point | 288 to 292 °C (550 to 558 °F; 561 to 565 K) |

| Hazards | |

| MSDS | External MSDS |

| EU classification | |

| R-phrases | R23 R24 R25 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide, also called DEET (/diːt/) or diethyltoluamide, is a slightly yellow oil. It is the most common active ingredient in insect repellents. It is intended to be applied to the skin or to clothing, and provides protection against mosquitos, ticks, fleas, chiggers, leeches, and many other biting insects.

History

DEET was developed by the United States Army, following its experience of jungle warfare during World War II. It was originally tested as a pesticide on farm fields, and entered military use in 1946 and civilian use in 1957. It was used in Vietnam and Southeast Asia.[1]

Preparation

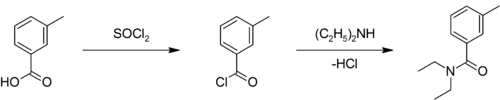

A slightly yellow liquid at room temperature, it can be prepared by converting m-toluic acid (3-methylbenzoic acid) to the corresponding acyl chloride, and allowing it to react with diethylamine:[2][3]

Mechanism and effectiveness

DEET was historically believed to work by blocking insect olfactory receptors for 1-octen-3-ol, a volatile substance that is contained in human sweat and breath. The prevailing theory was that DEET effectively "blinds" the insect's senses so that the biting/feeding instinct is not triggered by humans or other animals which produce these chemicals. DEET does not appear to affect the insect's ability to smell carbon dioxide, as had been suspected earlier.[4][5]

However, more recent evidence shows that DEET serves as a true repellent in that mosquitoes intensely dislike the smell of the chemical repellent.[6] A type of olfactory receptor neuron in special antennal sensilla of mosquitoes that is activated by DEET, as well as other known insect repellents such as eucalyptol, linalool, and thujone, has been identified. Moreover, in a behavioral test, DEET had a strong repellent activity in the absence of body odor attractants such as 1-octen-3-ol, lactic acid, or carbon dioxide. Female and male mosquitoes showed the same response.[7][6]

A recent structural study has revealed that DEET binds to Anopheles gambiae odorant binding protein 1 (AgamOBP1) with high shape complementarity, suggesting that AgamOBP1 is a molecular target of DEET and perhaps other repellents.[8]

A 2013 study suggests that mosquitoes can at least temporarily overcome or adapt to the repellant effect of DEET after an initial exposure, representing a non-genetic behavioral change.[9] This observation, if verified, has significant implications for how repellant effectiveness should be assessed.

A highly conserved protein member of the ionotropic receptor family, IR40a, has recently been identified as a putative DEET receptor in the fly antenna. The neurons expressing IR40a respond to DEET in an IR40a dependent manner. Avoidance to DEET vapors is lost in flies that lack IR40a. Other repellent chemicals that are structurally related to DEET also activate the same receptor and repel mosquitoes and flies, suggesting that this receptor can be used to screen for new repellents.[10]

The hypothesis that IR40a is involved in DEET reception in mosquitoes has been tested in the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus.[11] Reducing CquiIR40a transcript levels did not affect DEET-elicited behavior or electroanetnnographic (EAG) responses thus suggesting that IR40a is not involved in DEET reception in Culex mosquitoes. An antennae-specific odorant receptor, CquiOR136, was demonstrated to respond to DEET and other insect repellents. Similar knockdown experiments showed that EAG responses to DEET recorded from mosquitoes with reduced CquiOR136 transcript levels were dramatically lower. Additionally, behavioral tests showed that this phenotype was not repelled by DEET. In conclusion, these results suggest that CquiOR136, not CquiIR40a, is involved in DEET reception in the southern house mosquito.[11]

Concentrations

DEET is often sold and used in spray or lotion in concentrations up to 100%.[12] Consumer Reports found a direct correlation between DEET concentration and hours of protection against insect bites. 100% DEET was found to offer up to 12 hours of protection while several lower concentration DEET formulations (20%-34%) offered 3–6 hours of protection.[13] Other research has corroborated the effectiveness of DEET.[14] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends 30-50% DEET to prevent the spread of pathogens carried by insects.[15]

Effects on health

As a precaution, manufacturers advise that DEET products should not be used under clothing or on damaged skin, and that preparations be washed off after they are no longer needed or between applications.[16] DEET can act as an irritant;[4] in rare cases, it may cause severe epidermal reactions.[16]

In the DEET Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED), the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported 14 to 46 cases of potential DEET-associated seizures, including 4 deaths. The EPA states: "... it does appear that some cases are likely related to DEET toxicity," but observed that with 30% of the US population using DEET, the likely seizure rate is only about one per 100 million users.[17]

The Pesticide Information Project of Cooperative Extension Offices of Cornell University states that "Everglades National Park employees having extensive DEET exposure were more likely to have insomnia, mood disturbances and impaired cognitive function than were lesser exposed co-workers".[18]

When used as directed, products containing between 10% to 30% DEET have been found by the American Academy of Pediatrics to be safe to use on children, as well as adults, but recommends that DEET not be used on infants less than two months old.[16]

Citing human health reasons, Health Canada barred the sale of insect repellents for human use that contained more than 30% DEET in a 2002 re-evaluation. The agency recommended that DEET-based products be used on children between the ages of 2 and 12 only if the concentration of DEET is 10% or less and that repellents be applied no more than 3 times a day, children under 2 should not receive more than 1 application of repellent in a day and DEET-based products of any concentration should not be used on infants under 6 months.[19][20]

DEET is commonly used in combination with insecticides and can strengthen the toxicity of carbamate insecticides,[21] which are also acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. These findings indicate that DEET has neurological effects on insects in addition to known olfactory effects, and that its toxicity is strengthened in combination with other insecticides.

Effects on materials

DEET is an effective solvent,[4] and may dissolve some plastics, rayon, spandex, other synthetic fabrics, and painted or varnished surfaces including nail polish.

Effects on the environment

Though DEET is not expected to bioaccumulate, it has been found to have a slight toxicity for coldwater fish such as rainbow trout[22] and tilapia,[23] and it also has been shown to be toxic for some species of freshwater zooplankton.[24] DEET has been detected at low concentrations in waterbodies as a result of production and use, such as in the Mississippi River and its tributaries, where a 1991 study detected levels varying from 5 to 201 ng/L.[25]

See also

- Beautyberry

- Chikungunya

- Citronella oil

- DDT another means of disease vector control

- Icaridin

- Lemon eucalyptus

- Mosquito coil

- Permethrin, a pyrethroid

- SS220

- Anthranilate-based insect repellents

References

- ↑ Committee on Gulf War and Health: Literature Review of Pesticides and Solvents (2003). Gulf War and Health: Volume 2. Insecticides and Solvents (AVAILABLE ONLINE). Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-11389-2.

- ↑ Wang, Benjamin J-S. (1974). "An interesting and successful organic experiment (CEC)". J. Chem. Ed. 51 (10): 631. doi:10.1021/ed051p631.2.

- ↑ Donald L. Pavia (2004). Introduction to organic laboratory techniques (GOOGLE BOOKS EXCERPT). Cengage Learning. pp. 370–376. ISBN 978-0-534-40833-6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Anna Petherick (2008-03-13). "How DEET jams insects' smell sensors". Nature News. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ↑ Mathias Ditzen, Maurizio Pellegrino, Leslie B. Vosshall (2008). "Insect Odorant Receptors Are Molecular Targets of the Insect Repellent DEET". Sciencexpress 319 (5871): 1838–42. doi:10.1126/science.1153121. PMID 18339904.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Syed, Z.; Leal, WS (2008). "Mosquitoes smell and avoid the insect repellent DEET". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 (36): 13598–603. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805312105. PMC 2518096. PMID 18711137.

- ↑ Fox, Maggie; David Wiessler (Aug 18, 2008). "For mosquitoes, DEET just plain stinks". Washington. Reuters. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ↑ Tsitsanou, K.E. et al. (2011). "Anopheles gambiae odorant binding protein crystal complex with the synthetic repellent DEET: implications for structure-based design of novel mosquito repellents". Cell Mol Life Sci 69 (2): 283–97. doi:10.1007/s00018-011-0745-z. PMID 21671117.

- ↑ Stanczyk, Nina M.; Brookfield, John F. Y.; Field, Linda M.; Logan, James G. (2013). Vontas, John, ed. "Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes Exhibit Decreased Repellency by DEET following Previous Exposure". Plos One (20 February 2013) 8 (2): e54438. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054438. Lay summary – BBC news (21 February 2013)

- ↑ Kain, Pinky; Boyle, Sean Michael; Tharadra, Sana Khalid; Guda, Tom; Pham, Christine; Dahanukar, Anupama; Ray, Anandasankar (2013). "Odour receptors and neurons for DEET and new insect repellents". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature12594.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Mosquito odorant receptor for DEET and methyl jasmonate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. October 27, 2014.

- ↑ Record in the Household Products Database of NLM

- ↑ Matsuda, Brent M.; Surgeoner, Gordon A.; Heal, James D.; Tucker, Arthur O.; Maciarello, Michael J. (1996). "Essential oil analysis and field evaluation of the citrosa plant "Pelargonium citrosum" as a repellent against populations of Aedes mosquitoes". Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 12 (1): 69–74. PMID 8723261.

- ↑ David Williamson (3 July 2002). "Independent study: DEET products superior for fending off mosquito bites" (Press release). University of North Carolina.

- ↑ "Protection against Mosquitoes, Ticks, Fleas and Other Insects and Arthropods". Travelers' Health - Yellow Book. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009-02-05.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Insect Repellent Use and Safety". West Nile Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007-01-12.

- ↑ "Reregistration Eligibility Decision: DEET" (PDF). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Prevention, Pesticides, and Toxic Substances. September 1998. pp. pp39–40. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ↑ "DEET". Pesticide Information Profile. EXTOXNET. October 1997. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ↑ "Insect Repellents". Healthy Living. Health Canada. August 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ "Re-evaluation Decision Document: Personal insect repellents containing DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide and related compounds)". Consumer Product Safety. Health Canada. 2002-04-15. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ Moss (1996). "Synergism of Toxicity of N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide to German Cockroaches (Othoptera: Blattellidae) by Hydrolytic Enzyme Inhibitors". J. Econ. Entomol. 89 (5): 1151–1155. PMID 17450648.

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1980. Office of Pesticides and Toxic Substances. N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (Deet) Pesticide Registration Standard. December, 1980. 83 pp.

- ↑ Mathai, AT; Pillai, KS; Deshmukh, PB (1989). "Acute toxicity of deet to a freshwater fish, Tilapia mossambica : Effect on tissue glutathione levels". Journal of Environmental Biology 10 (2): 87–91.

- ↑ J. Seo, Y. G. Lee, S. D. Kim, C. J. Cha, J. H. Ahn and H. G. Hur (2005). "Biodegradation of the Insecticide N,N-Diethyl-m-Toluamide by Fungi: Identification and Toxicity of Metabolites". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 48 (3): 323–328. doi:10.1007/s00244-004-0029-9. PMID 15750774.

- ↑ "Errol Zeiger, Raymond Tice, Brigette Brevard, (1999) N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) [134-62-3] - Review of Toxicological Literature" (PDF). Retrieved July 20. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)

Further reading

- M. S. Fradin (1 June 1998). "Mosquitoes and Mosquito Repellents: A Clinician's Guide". Ann Intern Med 128 (11): 931–940. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-128-11-199806010-00013. PMID 9634433.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to DEET. |

- DEET General Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- DEET Technical Fact Sheet - National Pesticide Information Center

- West Nile Virus Resource Guide - National Pesticide Information Center

- Health Advisory: Tick and Insect Repellents, New York State

- US Centers for Disease Control information on DEET

- US Environmental Protection Agency information on DEET

- Review of scientific literature on DEET (from a RAND Corporation report on Gulf War illnesses)