Cyclic sediments

Cyclic sediments (also called rhythmic sediments[1]) are sequences of sedimentary rocks that are characterised by repetitive patterns of different rock types (strata) within the sequence. Cyclic sediments can be identified as either autocyclic or allocyclic, and can be hundreds or even thousands of metres thick. The study of sequence stratigraphy was developed from controversies over the causes of cyclic sedimentation.[2]

Processes that create cyclic sediments

Cyclic sedimentation occurs when there is a repetition of a specific series of connected events that affects the environment the sediments are deposited in. Changes in the environment of deposition change the type and amount of sediments that are deposited, resulting in different sedimentary rock types. A series of connected events produces a distinctive and repetitive series of strata that are arranged vertically. At least one rock type, which is regarded as the starting point, must be repeated.[1]

Based on the processes that generate the cyclic deposits, two types of sedimentary cyclic successions — autocycles and allocycles — can be distinguished.

Autocycles

Autocycles are cyclic sediments that are created by processes that only take place within the basin that the sediments are deposited in. Tides and storms are examples of the types of processes that create autocycles. Autocycles show limited stratigraphic continuity.[3]

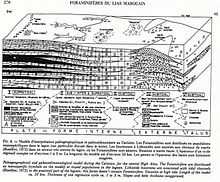

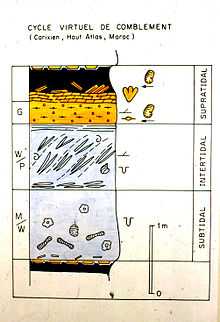

An example of autocyclic sedimentation on a carbonate platform by Septfontaine M. (1985): Depositional environments and associated foraminifera (lituolids) in the middle liasic carbonate platform of Morocco.- Rev. de Micropal., 28/4, 265-289. See also www.palgeo.ch/publications.

-

"Shallowing upward" metric first order cycle in the Middle Liassic platform of the High Atlas, Morocco. Algal dolomitized laminations on top.

-

Recent equivalent of an emersive autocyclic cycle in a lagoonal to supratidal environment. Algal mats in yellow. Tunisia.

-

Stalactitic cement from a sample in the supratidal zone in vadose environment (air within the sediment), top of regressive cycle, middle Lias, High Atlas. Thin section, L = 0,5mm.

-

Hurricane breccia cemented on the surface of a bed, top of a "shallowing upward" cycle. Middle Lias, High Atlas.

-

Top of a metric regressive cycle with desiccations, surface of bed dolomitised. Middle liassic of the High Atlas, Morocco.

-

Washover, ammonites and belemnites (by storms) on top of a regressive cycle, supratidal environment. Middle liassic of the High Atlas, Morocco.

-

Giant dinosaur tracks, in a muddy sediment on top of a metric regressive cycle. Middle liassic, High Atlas, Morocco.

-

Metric to hectometric regressive cycles (related to an acceleration of the rate of subsidence); South of the High Atlas, Morocco.

Seasonal changes in weather can create cyclic sediments in the form of alternating bands of clay and silt (also known as varves). For example, in a glacial region where sediments are deposited in a lake, coarse sediments that are trapped in ice are released when the ice melts in the summer. This creates paler, coarser silt bands in the lake deposits. In winter, melting is at a minimum, meaning that only fine material is supplied to the lake, causing thin clay layers.[4] Because the cycles are limited to the depositional basin, the lateral extent of the resultant strata are limited. The time period over which autocycles form are usually less than the time periods of allocyclic deposits.[1]

Allocycles

Allocycles are cycles of sediments caused by processes that also occur outside the depositional basin. Sea level fluctuations, climate changes and tectonic activity are examples of these kinds of processes. Allocyclic successions can extend over great distances.[3]

-

"Shallowing upward" cycles in the lagoonal Liassic platform of the Musandam Peninsula(Oman). Possible allocyclic origin.

-

Possible allocyclic metric cycles, arranged in decametric sequences, limited by yellow algal, dolomitized levels, below depositional hiatus.

-

"Shallowing upward" cycles in the Middle Jurassic (Saghtan form.) of the jbel Laghdar Range (Oman).

Changes in sea level can create cyclic sediments of limestones, shales, coals and seat earths. For these cycles to have been created, the environment at the site of deposition must have changed radically from marine to deltaic, then lagoonal and then continental environments.[4] One cause of sea level change is the advance or retreat of continental glaciers caused by climate change. Tectonic movements can affect the environment of deposition by changing water depth. Allocyclic cycles can extend over great distances and are not limited to a single depositional basin.[1] Metric sedimentary carbonate cycles could be related to an astronomical (Milankovitch) precession influence (through thermic dilatation of oceans ?) on an estimated 20.000 years scale, according to numerous authors interpretations. But these beds are of no use in correlation, even at hectometric to kilometric scale, and certainly not a "high resolution" tool for stratigraphy without a severe biostratigraphic control !

Problems with the study of cyclic sediments

The debate about the causes of cyclic sedimentation has been contentious in the past, and it remains unresolved. Sequence stratigraphy, the study of sea level change through the examination of sedimentary deposits, was developed from the centuries-old controversy over the origin of cyclic sedimentation and the relative importance of eustatic and tectonic factors on sea level change.[2]

Another problem with the study of cyclic sediments is that different researchers have different criteria with which they identify cycles and the surfaces that separate the sedimentary layers within the cycles. There is also not a consistent terminology and classification scheme to describe the nature of the cycles seen in the stratigraphic record. This is mainly because absolute age dating is not precise enough at present.[1]

References

• Septfontaine, M. (1985): Milieux de dépôts et foraminifères (Lituolidae) de la plate-forme carbonatée du Lias moyen au Maroc.- Rev. Micropaléont., 28/4, 265-289. (Le modèle ancien proposé ci-dessous a son équivalent actuel au fond du golfe de Gabès et dans les chotts associés, voir Davaud & Septfontaine, 1995.

• Davaud, E. & Septfontaine, M. (1995): Post-Mortem onshore transportation of epiphytic foraminifera: recent example from the Tunisian coastline.- Jour. Sediment. Research, 65/1A, 136-142.

• Septfontaine, M. & De Matos, E. (1998): Pseudodictyopsella jurassica nov. gen., nov. sp., a new foraminifera from the Earlay Middle Jurassic of the Musandam Peninsula. Sedimentological and stratigraphical context.- Rev. Micropaléont., 41/1,71-87. (Dans cet article, on note l'absence du genre Orbitammina en Oman, souvent confondu avec Timidonella par les auteurs Anglo-Saxons).

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 V Cotti Ferrero, Celestina (2004-01-01). Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0872-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Emery (1996-10-01). Sequence Stratigraphy. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-632-03706-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Flugel, Erik (2004-09-15). Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks. Springer. ISBN 3-540-22016-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pitts, John (1985-06-30). A Manual of Geology for Civil Engineers. World Scientific. ISBN 9971-978-05-9.