Cushitic languages

| Cushitic | |

|---|---|

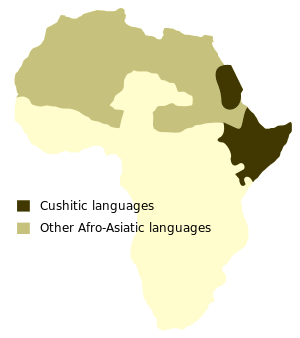

| Geographic distribution: | Northeast Africa |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Cushitic |

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5: | cus |

| Glottolog: | cush1243[1] |

| |

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa (Somalia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Ethiopia), as well as the Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), and parts of the African Great Lakes region (Tanzania and Kenya). The branch is named after the Biblical character Cush, who is identified as an ancestor of the speakers of these specific languages as early as 947 CE (in Al-Masudi's Arabic history Meadows of Gold).

The most populous Cushitic language is Oromo (including all its variations) with about 35 million speakers, followed by Somali with about 18 million speakers, and Sidamo with about 3 million speakers. Other Cushitic languages with more than one million speakers are Afar (1.5 million) and Beja (1.2 million). Somali, one of the official languages of Somalia, is the only Cushitic language accorded official status in any country. Along with Afar, it is also one of the recognized national languages of Djibouti.

Additionally, the languages spoken in the ancient Kerma Culture in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan and in the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture in the Great Lakes area are believed to have belonged to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family.

Composition

The Cushitic languages are usually considered to include the following branches:

- Beja (North Cushitic)

- Central Cushitic (Agaw)

- Highland East Cushitic (Sidamic)

- Lowland East Cushitic

- Dullay

- South Cushitic

Lowland and Highland East Cushitic are commonly combined with Dullay into a single branch called East Cushitic.

| Greenberg (1963) | Newman (1980) | Fleming (post-1981) | Ehret (1995) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(excludes Omotic) |

|

|

| Orel & Stobova (1995) | Diakonoff (1996) | Militarev (2000) | Ethnologue (2013) |

|

(Does not include Omotic) |

|

|

Divergent languages

The Beja language, or North Cushitic, is sometimes listed as a separate branch of Afroasiatic. However, it is more often included within the Afro-Asiatic family's Cushitic branch.

There are also a few poorly classified languages, including Yaaku, Dahalo, Aasax, Kw'adza, Boon, the Cushitic element of Mbugu (Ma’a) and Ongota. There is a wide range of opinions as to how these languages are interrelated.[2]

The positions of the Dullay languages and Yaaku are uncertain. These have traditionally been assigned to an East Cushitic branch along with Highland (Sidamic) and Lowland East Cushitic. However, Hayward believes East Cushitic may not be a valid node and that its constituents should be considered separately when attempting to work out the internal relationships of Cushitic.[2]

The Afroasiatic identity of Ongota is also broadly questioned, as is its position within Afroasiatic among those who accept it, due to the "mixed" appearance of the language and a paucity of research and data. Harold Fleming (2006) proposes that Ongota constitutes a separate branch of Afroasiatic.[3] Bonny Sands (2009) believes the most convincing proposal is by Savà and Tosco (2003), namely that Ongota is an East Cushitic language with a Nilo-Saharan substratum. In other words, it would appear that the Ongota people once spoke a Nilo-Saharan language but then shifted to speaking a Cushitic language while retaining some characteristics of their earlier Nilo-Saharan language.[4][5]

Hetzron (1980:70ff)[6] and Ehret (1995) have suggested that the Rift languages (South Cushitic) are a part of Lowland East Cushitic, the only one of the six groups with much internal diversity.

Cushitic was traditionally seen as also including the Omotic languages, then called West Cushitic. However, this view has largely been abandoned, with Omotic generally agreed to be an independent branch of Afroasiatic, primarily due to the work of Harold C. Fleming (1974) and M. Lionel Bender (1975).

Extinct languages

A number of extinct populations are believed to have spoken Afro-Asiatic languages of the Cushitic branch. According to Peter Behrens (1981) and Marianne Bechaus-Gerst (2000), linguistic evidence indicates that the peoples of the Kerma Culture in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan spoke Cushitic languages.[7][8] The Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key pastoralism related loanwords that are of proto-Highland East Cushitic origin, including the terms for sheep/goatskin, hen/cock, livestock enclosure, butter and milk. This in turn suggests that the Kerma population — which, along with the C-Group Culture, inhabited the Nile Valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers — spoke Afro-Asiatic languages.[7]

Additionally, historiolinguistics indicate that the makers of the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic (Stone Bowl Culture) in the Great Lakes area likely spoke South Cushitic languages.[9] Christopher Ehret (1998) proposes that among these idioms were the now extinct Tale and Bisha languages, which were identified on the basis of loanwords.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Cushitic". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Richard Hayward, "Afroasiatic", in Heine & Nurse, 2000, African Languages

- ↑ Harrassowitz Verlag - The Harrassowitz Publishing House

- ↑ Savà, Graziano; Tosco, Mauro (2003). "The classification of Ongota". In Bender, M. Lionel et al. Selected comparative-historical Afrasian linguistic studies. LINCOM Europa.

- ↑ Sands, Bonny (2009). "Africa’s Linguistic Diversity". Language and Linguistics Compass 3 (2): 559–580. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00124.x.

- ↑ Robert Hetzron, "The Limits of Cushitic", Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 2. 1980, 7–126.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Marianne Bechaus-Gerst, Roger Blench, Kevin MacDonald (ed.) (2014). The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography - "Linguistic evidence for the prehistory of livestock in Sudan" (2000). Routledge. pp. 453–457. ISBN 1135434166. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ Behrens, Peter (1986). Libya Antiqua: Report and Papers of the Symposium Organized by Unesco in Paris, 16 to 18 January 1984 - "Language and migrations of the early Saharan cattle herders: the formation of the Berber branch". Unesco. p. 30. ISBN 9231023764. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ↑ Ambrose, Stanley H. (1984). From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa - "The Introduction of Pastoral Adaptations to the Highlands of East Africa". University of California Press. pp. 234 & 223. ISBN 0520045742. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Roland Kießling, Maarten Mous & Derek Nurse. "The Tanzanian Rift Valley area". Maarten Mous. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

References

- Ethnologue on the Cushitic branch

- Bender, Marvin Lionel. 1975. Omotic: a new Afroasiatic language family. Southern Illinois University Museum series, number 3.

- Bender, M. Lionel. 1986. A possible Cushomotic isomorph. Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 6:149-155.

- Fleming, Harold C. 1974. Omotic as an Afroasiatic family. In: Proceedings of the 5th annual conference on African linguistics (ed. by William Leben), p 81-94. African Studies Center & Department of Linguistics, UCLA.

- Roland Kießling & Maarten Mous. 2003. The Lexical Reconstruction of West-Rift Southern Cushitic. Cushitic Language Studies Volume 21

- Lamberti, Marcello. 1991. Cushitic and its classification. Anthropos 86(4/6):552-561.

- Zaborski, Andrzej. 1986. Can Omotic be reclassified as West Cushitic? In Gideon Goldenberg, ed., Ethiopian Studies: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, pp. 525–530. Rotterdam: Balkema.

- Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary (1995) Christopher Ehret

External links

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Cushitic languages

- BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HIGHLAND EAST CUSHITIC

- Faculty of Humanities - Leiden University

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||