Cumae

| Cumae | |

|---|---|

|

Κύμη / Κύμαι / Κύμα Cuma | |

|

The acropolis of Cumae seen from the lower city. | |

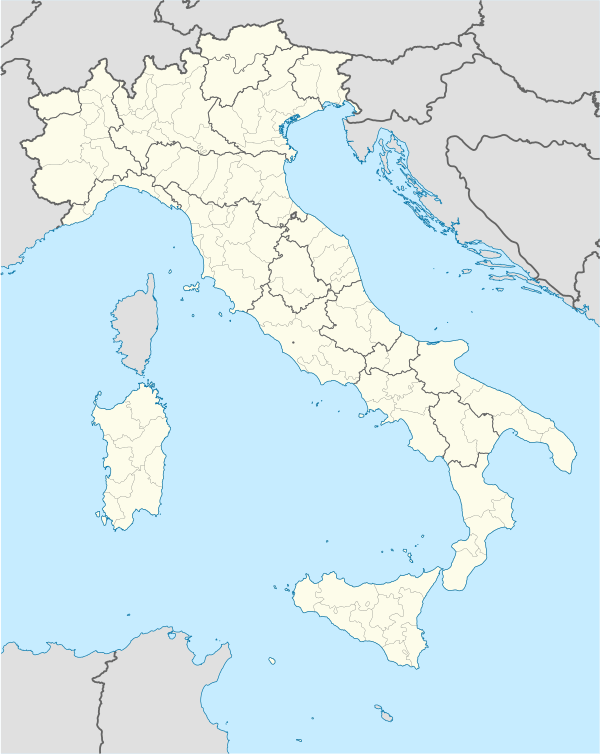

Shown within Italy | |

| Location | Cuma, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy |

| Region | Magna Graecia |

| Coordinates | 40°50′55″N 14°3′13″E / 40.84861°N 14.05361°ECoordinates: 40°50′55″N 14°3′13″E / 40.84861°N 14.05361°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Colonists from Euboea |

| Founded | 8th century BC |

| Abandoned | 1207 AD |

| Periods | Archaic Greek to High Medieval |

| Associated with | Cumaean Sibyl, Gaius Blossius |

| Events | Battle of Cumae |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Direzione Regionale per i Beni Culturali e Paesaggistici della Campania |

| Website | Sito Archeologico di Cuma (Italian) |

Cumae (Ancient Greek: Κύμη (Kumē) or Κύμαι (Kumai) or Κύμα (Kuma);[1] Italian: Cuma) was an ancient city of Magna Graecia on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BC, Cumae was the first Greek colony on the mainland of Italy and the seat of the Cumaean Sibyl. The ruins of the city lie near the modern village of Cuma, a frazione of the comune Bacoli in the Province of Naples, Campania, Italy.

The Sibyl of Cumae

Cumae is perhaps most famous as the seat of the Cumaean Sibyl. Her sanctuary is now open to the public.

In Roman mythology, there is an entrance to the underworld located at Avernus, a crater lake near Cumae, and was the route Aeneas used to descend to the Underworld.

Early history

The settlement, in a location that was already occupied, is believed to have been founded in the 8th century BC[2] by Euboean Greeks, originally from the cities of Eretria and Chalcis in Euboea, which was accounted its mother-city by agreement among the first settlers. They were already established at Pithecusae (modern Ischia);[3] they were led by the paired oecists (colonizers) Megasthenes of Chalcis and Hippocles of Cyme.[4]

The Greeks were planted upon the earlier dwellings of indigenous, Iron Age peoples whom they supplanted; a memory of them was preserved as cave-dwellers named Cimmerians, among whom there was already an oracular tradition.[5] Its name refers to the peninsula of Cyme in Euboea. The colony was also the entry point in the Italian peninsula for the Euboean alphabet, the local variant of the Greek alphabet used by its colonists, a variant of which was adapted and modified by the Etruscans and then by the Romans and became the Latin alphabet still used worldwide today.

The colony thrived. By the 8th century it was strong enough to send Perieres and a group with him, who were among the founders of Zancle in Sicily, and another band had returned to found Triteia in Achaea, Pausanias was told.[6] It spread its influence throughout the area over the 7th and 6th centuries BC, gaining sway over Puteoli and Misenum and, thereafter, founding Neapolis in 470 BC. All these facts were recalled long afterwards; Cumae's first brief contemporary mention in written history is in Thucydides.

The growing power of the Cumaean Greeks led many indigenous tribes of the region to organize against them, notably the Dauni and Aurunci with the leadership of the Capuan Etruscans. This coalition was defeated by the Cumaeans in 524 BC under the direction of Aristodemus, called Malacus, a successful man of the people who overthrew the aristocratic faction, became a tyrant himself, and was assassinated.[7]

Contact between the Romans and the Cumaeans is recorded during the reign of Aristodemus. Livy states that immediately prior to the war between Rome and Clusium, the Roman senate sent agents to Cumae to purchase grain in anticipation of a siege of Rome.[8] Also Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last legendary King of Rome, lived his life in exile with Aristodemus at Cumae after the Battle of Lake Regillus and died there in 495 BC.[9] Livy records that Aristodemus became the heir of Tarquinius, and in 492 when Roman envoys travelled to Cumae to purchase grain, Aristodemus seized the envoys' vessels on account of the property of Tarquinius which had been seized at the time of Tarquinius' exile.[10]

Also during the reign of Aristodemus, the Cumaean army assisted the Latin city of Aricia to defeat the Etruscan forces of Clusium.

The combined fleets of Cumae and Syracuse defeated the Etruscans at the Battle of Cumae in 474 BC.

Oscan and Roman Cumae

The Greek period at Cumae came to an end in 421 BC, when the Oscans broke down the walls and took the city, ravaging the countryside. Some survivors fled to Neapolis.[11] Cumae came under Roman rule with Capua and in 338 was granted partial citizenship, a civitas sine suffragio. In the Second Punic War, in spite of temptations to revolt from Roman authority,[12] Cumae withstood Hannibal's siege, under the leadership of Tib. Sempronius Gracchus.[13]

The early presence of Christianity in Cumae is shown by the 2nd-century work The Shepherd of Hermas, in which the author tells of a vision of a woman, identified with the church, who entrusts him with a text to read to the presbyters of the community in Cuma. At the end of the 4th century, the temple of Zeus at Cumae was transformed into a Christian basilica.

The first historically documented bishop of Cumae was Adeodatus, a member of a synod convoked by Pope Hilarius in Rome in 465. Another was Misenus, who was one of the two legates that Pope Felix III sent to Constantinople and who were imprisoned and forced to receive Communion with Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople in a celebration of the Divine Liturgy in which Peter Mongus and other Miaphysites were named in the diptychs, an event that led to the Acacian Schism. Misenus was excommunicated on his return but was later rehabilitated and took part as bishop of Cumae in two synods of Pope Symmachus. Pope Gregory the Great entrusted the administration of the diocese of Cumae to the bishop of Misenum. Later, both Misenum and Cumae ceased to be residential sees and the territory of Cumae became part of the diocese of Aversa after the destruction of Cumae in 1207.[14][15][16] Accordingly, Cumae is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[17]

Under Roman rule, "quiet Cumae" slumbered until the disasters of the Gothic Wars (535–554), when it was repeatedly attacked, as the only fortified city in Campania aside from Neapolis: Belisarius took it in 536, Totila held it, and when Narses gained possession of Cumae, he found he had won the whole treasury of the Goths. In 1207, forces from Naples, acting for the boy-King of Sicily, destroyed the city and its walls, as the stronghold of a nest of bandits.

The seaward side of the large rise on which Cumae was built was used as a bunker and gun emplacement by the Germans during World War II.

Gallery

-

The walls of the acropolis

-

The Temple of Apollo

-

The Temple of Diana

-

The Temple of Zeus

-

Acropolis seen from west

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Perseus: Κύ̂μα

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea placed Cumae's Greek foundation at 1050 BC; modern archaeology has not detected the first settlers' graves, but fragments of Greek pottery ca 750-40 have been found by the city wall (Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008:140).

- ↑ Strabo, v.4.

- ↑ Lane Fox 2008:140 notes that whether the Euboeans were from the Ischian colony or freshly arrived is a moot question

- ↑ Strabo, v.5, noted in Elizabeth Hazelton Haight, "Cumae in Legend and History" The Classical Journal 13.8 (May 1918:565-578) p. 567.

- ↑ Pausanias, vii.22.6.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, vii.3; Plutarch tells the story of Xenocrite, the girl who roused the Cumaeans against Aristodemus, in De mulierum virturibus 26.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.9

- ↑ Livy, ii.21; Cicero, Tusculan Disputations iii.27.

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2:34

- ↑ Livy, iv.44; Diodorus Siculus, xii. 76.

- ↑ Livy, xxiii.35

- ↑ Livy, xxiii.35-37.

- ↑ Camillo Minieri Riccio, Cenni storici sulla distrutta città di Cuma, Napoli 1846, pp. 37–38

- ↑ Giuseppe Cappelletti, Le Chiese d'Italia dalla loro origine sino ai nostri giorni, vol. XIX, Venezia 1864, pp. 526–535

- ↑ Francesco Lanzoni, Le diocesi d'Italia dalle origini al principio del secolo VII (an. 604), vol. I, Faenza 1927, pp. 206–210

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 877

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cumae. |

- Official website (Italian)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||