Cubane

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Cubane[1] | |||

| Other names

Pentacyclo[4.2.0.02,5.03,8.04,7]octane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 277-10-1 | |||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:33014 | ||

| ChemSpider | 119867 | ||

| |||

| Jmol-3D images | Image | ||

| PubChem | 136090 | ||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C8H8 | |||

| Molar mass | 104.15 g/mol | ||

| Density | 1.29 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 131 °C (268 °F; 404 K) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Related hydrocarbons |

Cuneane Dodecahedrane Tetrahedrane Prismane Prismane C8 | ||

| Related compounds |

Heptanitrocubane Octanitrocubane Octaazacubane | ||

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

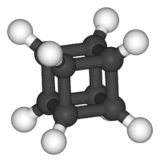

Cubane (C8H8) is a synthetic hydrocarbon molecule that consists of eight carbon atoms arranged at the corners of a cube, with one hydrogen atom attached to each carbon atom. A solid crystalline substance, cubane is one of the Platonic hydrocarbons. It was first synthesized in 1964 by Philip Eaton, a professor of chemistry at the University of Chicago.[2] Before Eaton and Cole's work, researchers believed that cubic carbon-based molecules could not exist, because the unusually sharp 90-degree bonding angle of the carbon atoms was expected to be too highly strained, and hence unstable. Once formed, cubane is quite kinetically stable, due to a lack of readily available decomposition paths.

The other Platonic hydrocarbons are dodecahedrane and tetrahedrane.

Cubane and its derivative compounds have many important properties. The 90-degree bonding angle of the carbon atoms in cubane means that the bonds are highly strained. Therefore, cubane compounds are highly reactive, which in principle may make them useful as high-density, high-energy fuels and explosives (for example, octanitrocubane and heptanitrocubane).

Cubane also has high density and crystallinity for a hydrocarbon, further contributing to its ability to store large amounts of energy, which would reduce the size and weight of fuel tanks in aircraft and especially rocket boosters. Researchers are looking into using cubane and similar cubic molecules in medicine and nanotechnology.

Synthesis

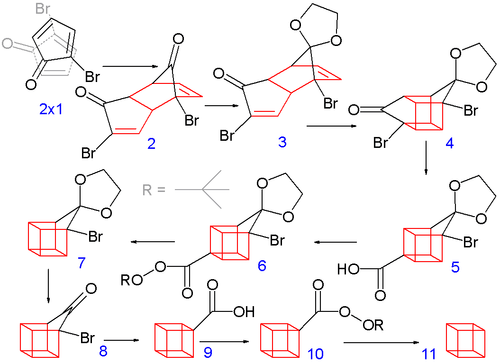

The classic 1964 synthesis starts from 2-cyclopentenone (compound 1.1 in scheme 1):[2][3]

Reaction with N-bromosuccinimide in carbon tetrachloride places an allylic bromine atom in 1.2 and further bromination with bromine in pentane - methylene chloride gives the tribromide 1.3. Two equivalents of hydrogen bromide are eliminated from this compound with diethylamine in diethyl ether to bromocyclopentadienone 1.4

In the second part (scheme 2), the spontaneous Diels-Alder dimerization of 2.1 to 2.2 is analogous to the dimerization of cyclopentadiene to dicyclopentadiene. For the next steps to succeed, only the endo isomer should form; this happens because the bromine atoms, on their approach, take up positions as far away from each other, and from the carbonyl group, as possible. In this way the like-dipole interactions are minimized in the transition state for this reaction step. Both carbonyl groups are protected as acetals with ethylene glycol and p-toluenesulfonic acid in benzene; one acetal is then selectively deprotected with aqueous hydrochloric acid to 2.3

In the next step, the endo isomer 2.3 (with both alkene groups in close proximity) forms the cage-like isomer 2.4 in a photochemical [2+2] cycloaddition. The bromoketone group is converted to ring-contracted carboxylic acid 2.5 in a Favorskii rearrangement with potassium hydroxide. Next, the thermal decarboxylation takes place through the acid chloride (with thionyl chloride) and the tert-butyl perester 2.6 (with t-butyl hydroperoxide and pyridine) to 2.7; afterward, the acetal is once more removed in 2.8. A second Favorskii rearrangement gives 2.9, and finally another decarboxylation gives 2.10 and 2.11.

Inorganic cubes and related derivatives

The cube motif occurs outside of the area of organic chemistry. Prevalent non-organic cubes are the [Fe4-S4] clusters found pervasively iron-sulfur proteins. Such species contain sulfur and Fe at alternating corners. Alternatively such inorganic cube clusters can often be viewed as interpenetrated S4 and Fe4 tetrahedra. Many organometallic compounds adopt cube structures, examples being (CpFe)4(CO)4, (Cp*Ru)4Cl4, (Ph3PAg)4I4, and (CH3Li)4.

Reactions

Cuneane may be produced from cubane by a metal-ion-catalyzed σ-bond rearrangement.[4][5]

References

- ↑ According to page 41 of a 2004 IUPAC guide, cubane is the "preferred IUPAC name."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 ' 'Cubaneand Thomas W. Cole. Philip E. Eaton and Thomas W. Cole J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1964; 86(15) pp 3157 - 3158; doi:10.1021/ja01069a041.

- ↑ The Cubane System Philip E. Eaton and Thomas W. Cole J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1964; 86(5) pp 962 - 964; doi:10.1021/ja01059a072

- ↑ Michael B. Smith, Jerry March, March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry, 5th Ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2001, p. 1459. ISBN 0-471-58589-0

- ↑ K. Kindler, K. Lührs, Chem. Ber., vol. 99, 1966, p. 227.