Crystal River, Florida

| Crystal River, Florida | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

US 19-98 enters Crystal River. | |

| Nickname(s): Manatee Haven | |

| Motto: "Gem of the Nature Coast " | |

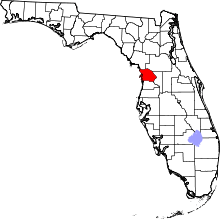

Location in Citrus County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 28°54′2″N 82°35′37″W / 28.90056°N 82.59361°WCoordinates: 28°54′2″N 82°35′37″W / 28.90056°N 82.59361°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.8 sq mi (17.7 km2) |

| • Land | 6.2 sq mi (16.0 km2) |

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (1.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 4 ft (1 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,108 |

| • Density | 502/sq mi (193.9/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP codes | 34423, 34428, 34429 |

| Area code(s) | 352 |

| FIPS code | 12-15775[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0281135[2] |

| Website |

www |

Crystal River is a city in Citrus County, Florida, United States. The population was 3,108 in the 2010 census.[3] (3,485 in 2000). According to the U.S Census estimates of 2012, the city had a population of 3,055.[4] The city was incorporated in 1903 and is the self professed "Home of the Manatee".[5] Crystal River Preserve State Park is located nearby, and Crystal River Archaeological State Park is located in the city's northwest side.

Crystal River is at the heart of the Nature Coast of Florida. The city is situated around Kings Bay, which is spring-fed and so keeps a constant 72 °F (22 °C) temperature year round. A cluster of 50 springs designated as a first-magnitude system feeds Kings Bay. A first-magnitude system discharges 100 cubic feet or more of water per second, which equals about 64 million gallons of water per day. Because of this discharge amount, the Crystal River Springs group is the second largest springs group in Florida, the first being Spring Creek Springs in Wakulla County near Tallahassee. Kings Bay is home to over 400 manatees during the winter when the water temperature in the Gulf of Mexico cools, and is the only place in the United States where people can legally interact with them in their natural conditions without that interaction being viewed as harassment by law enforcement agencies. Tourism based on watching and swimming with manatee is the fastest growing contribution to the local economy. In 2005 there was a movement to dissolve the city which did not succeed, and the city has since grown by annexation.

Crystal River was home to the Crystal River 3 Nuclear Power Plant. In 2012 the owners, Duke Energy, announced the closure of the plant.

Geography

Crystal River is located northwest of the center of Citrus County at 28°54′02″N 82°35′37″W / 28.900670°N 82.593699°W,[6] on the northeast side of Kings Bay and the Crystal River, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico. U.S. Routes 19 and 98 pass through the center of the city, leading south 7 miles (11 km) to Homasassa Springs and north 46 miles (74 km) to Chiefland. State Road 44 leads east from Crystal River 17 miles (27 km) to Inverness, the Citrus County seat.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city of Crystal River has a total area of 6.8 square miles (17.7 km2). 6.2 square miles (16.0 km2) of it is land and 0.66 square miles (1.7 km2) of it 9.35%, is water.[3]

History

In the Pleistocene era, the land on which Crystal River is located was vastly different from today. The west coast of Florida is thought to have extended an additional 50 to 60 miles (80 to 97 km) into the Gulf of Mexico.[7][8] During excavations for the Florida Nuclear Power Plant in 1969, scientists discovered rhinoceros and mastodon bones, as well as the shells of an extremely large armadillo and a large land tortoise.[7]

Around 500 B.C. mound-building Native Americans (possibly Deptford culture) built a settlement along the Crystal River, which in the present day is the Crystal River Archaeological State Park.[8] It was abandoned prior to European colonization for unknown reasons.[9] The obsolete Native American name for Crystal River was Weewahi Iaca.[7]

Following the Second Seminole War, settlers were encouraged into the area due to the passing of the Armed Occupation Act of 1842 by the United States federal government. Twenty-two men filed for patents for land in Crystal River.[8] By the mid-1800s, families began to settle in the Crystal River area.

Mail was delivered by horse and buggy, and a stagecoach came from Ocala (Fort King) to Crystal River, stopping at the Stage Stand, which today is the Stage Stand Cemetery in Homosassa.[8]

While no land battles were fought in the Crystal River area during the Civil War, there were many instances of skirmishes on the water directly off the coast of the Crystal and Homosassa rivers, as well as near Hickory Island in Yankeetown.[8] By the time of the Civil War, Florida was an important source and supplier of food and other goods such as beef, pork, fish, corn, sugar, cotton, naval stores and salt. The Union was aware of this, and soon after the war began, the Union Navy blockaded the entire coast of Florida.[7]

Following the Civil War, Crystal River grew. People from states to the north began to arrive, attracted by the area's mild climate and the potential of becoming wealthy growing citrus fruits. Early settlers to the area had found wild citrus trees growing in abundance, thanks in part to the Spanish explorers who had brought oranges with them on their ships and had discarded the seeds in the new world.[8] This gave rise to the planting of citrus groves. The "Big Freeze" of 1894-1895 destroyed most of the citrus groves in the county.[7]

A very early industry in the area was the turpentine business.[8] Many of the barges during the Civil War blockade had been carrying turpentine, likely from the turpentine still of William Turner, who resided in Red Level.[8] Other early industry in the Crystal River area included cedar mills. In 1882, James Williams moved his cedar mill to Crystal River, and began operating on King's Bay.[7][8] The mill produced pencil boards, which were then shipped to Jersey City, New Jersey, by ship, and later on by train. The Dixon Cedar Mill was one of the largest industries in Crystal River, providing employment to many in the area, including women and African Americans.[8]

Crystal River had been part of Hernando County since its inception in 1843. In 1844, the county name changed from "Hernando" to "Benton", in honor of Senator Thomas Hart Benton who had sponsored the Armed Occupation Act of 1842, which had brought settlers to the area.[7] The county name returned to Hernando in 1850.

By the late 1800s, the area along the west side of the county was growing rapidly, and the citizens of the area began to see a need for a new county with a county seat that was easier to reach. In 1887, Hernando County was divided into three parts: Pasco County, Hernando County, and Citrus County.[8] The town of Mannfield was named the temporary county seat for two years. Mannfield was chosen as it was in the geographic center of the new county and was more accessible to citizens. The site for the eventual county seat, Inverness, was decided by a vote in 1891.[7][8]

Phosphate was discovered in 1889 in the east side of Citrus County, and the phosphate industry grew rapidly. Historians have claimed it to be "one of the richest phosphate deposits in the world."[8] The phosphate industry would boom in Crystal River and Citrus County until 1914, when it could no longer be shipped due to World War I.

In 1888, the railroad reached Crystal River. The arrival of the railroad proved to be a boon; it provided an easier way to ship and receive goods, and it was an easier way for tourists to travel. Sport fishing became a draw for many wealthy northerners.[8]

Crystal River became a town in 1903. It was officially incorporated as a city on July 3, 1923.[10]

Demographics

As of the census of 2010,[4] there were 3,108 people (2012 Estimate: 3,055), 1,401 households, and 794 families residing in the city. The population density was 455.19 people per square mile (1178.9/km²). There were 2,036 housing units at an average density of 343.4 per square mile (132.5/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 83.4% White, 7.4% Black or African American, 0.30% Native American, 2.1% Asian, 0.10% Pacific Islander, 0% from other races, and 1.6% from two or more races. 5.20% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.[11]

There were 1,401 households out of which 18% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.0% were married couples living together, 9.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.3% were non-families.[12] 56.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 19.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.06 and the average family size was 2.61.

In the city the population was spread out with 15.9% under the age of 18, 3.7% from 18 to 24, 15.7% from 25 to 44, 31% from 45 to 64, and 33.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 56 years. The population was composed of 1,477 males and 1,631 females.

The median income for a household in the city was $35,503, and the median income for a family was $58,398. Males had a median income of $39,357 versus $25,417 for females. The per capita income for the city was $38,219. About 3.5% of families and 9.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.4% of those under age 18 and 9.5% of those aged 65 or over.[4]

Crystal River Mall opened north of the center of town in 1990.

Notable people

- Art Fleming, original host of Jeopardy!

- Mike Hampton, major league baseball player, attended Crystal River High School[13]

- Wendi Richter, professional wrestler[14]

- Ted Williams, famed baseball player; resident at the time of his death

See also

References

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Crystal River city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Dunn, Hampton (1989). Back Home: A History of Crystal River. Citrus County Bicentennial Steering Committee.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 Bash, Evelyn (2006). A History of Crystal River, Florida. Crystal River Heritage Council. ISBN 1-59872-315-4.

- ↑ Milanich, Jerald T. (1999). Famous Florida sites: Mount Royal and Crystal River. Gainesville [u.a.]: Univ. Press of Florida. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-8130-1694-0.

- ↑ "City of Crystal River, Florida". Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ "Crystal River, FL Population and Races". USA.com. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ "Crystal River, FL". Zip-Codes.com. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ http://mlb.mlb.com/team/player.jsp?player_id=115399

- ↑ Peeples, Lisa (July 5, 1989). "Crystal River woman is at top of her sport". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

External links

![]() Media related to Crystal River (city), Florida at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Crystal River (city), Florida at Wikimedia Commons

- City of Crystal River official website

- Crystal River News, historical newspaper for Crystal River openly accessible in the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- Citrus County Visitors & Convention Bureau

- Springs Coast Watershed - Florida DEP

| |||||||||||||||||||||