Crocodylomorpha

| Crocodylomorpha Temporal range: Late Triassic–Recent, 225–0Ma[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

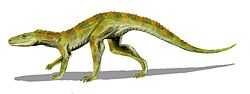

| Hesperosuchus an early crocodylomorph | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Bathyotica |

| Superorder: | Crocodylomorpha Hay, 1930 |

| Clades | |

|

See text. | |

Crocodylomorpha is a group of archosaurs that includes the crocodilians and their extinct relatives.

During Mesozoic and early Cenozoic times, Crocodylomorpha was far more diverse than it is now. Triassic forms were small, lightly built, active terrestrial animals. These were supplanted during the early Jurassic by various aquatic and marine forms. The Later Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Cenozoic saw a wide diversity of terrestrial and semi-aquatic lineages. "Modern" crocodilians do not appear until the Late Cretaceous. Among the largest crocodylomorphs are the 7 metre long Crocodylus anthropophagus, the 11 metre long Sarcosuchus imperator, the 12 metre long Deinosuchus hatcheri and the 9 metre long Machimosaurus hugii.

Evolutionary history

When their extinct species and stem group are examined, the crocodylian lineage (clade Crurotarsi) proves to have been a very diverse and adaptive group of reptiles. Not only are they an ancient group of animals, at least as old as the dinosaurs, they also evolved into a great variety of forms. The earliest forms, the sphenosuchians, evolved during the Late Triassic, and were highly gracile terrestrial forms built like greyhounds.

During the Jurassic and the Cretaceous, marine forms in the family Metriorhynchidae, such as Metriorhynchus, evolved forelimbs that were paddle-like and had a tail similar to modern fish. Dakosaurus andiniensis, a species closely related to Metriorhynchus, had a skull that was adapted to eat large marine reptiles. Several terrestrial species during the Cretaceous evolved herbivory, such as Simosuchus clarki and Chimaerasuchus paradoxus. A number of lineages during the Cenozoic became wholly terrestrial predators.

Phylogenetic definition

The Crocodylomorpha are defined phylogenetically by Sereno 2005 as "The most inclusive clade containing Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti 1768) but not Poposaurus gracilis Mehl 1915, Gracilisuchus stipanicicorum Romer 1972, Prestosuchus chiniquensis Huene 1942, Aetosaurus ferratus Fraas 1877."

This a stem-based definition and therefore includes all taxa closer to extant crocodilians than to other crurotarsan clades.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Historically, all known living and extinct crocodiles were indiscriminately lumped into the order Crocodilia. However, beginning in the late 1980s, many scientists began restricting the order Crocodilia to the living species and close extinct relatives such as Mekosuchus. The various other groups that had previously been known as Crocodilia were renamed Crocodylomorpha and the slightly more restricted Crocodyliformes.[2] Crocodylomorpha has been given the rank of superorder in some 20th and 21st century studies.[3]

The old Crocodilia was subdivided into the suborders:

- Eusuchia: true crocodilies (which includes crown-group Crocodylia)

- Mesosuchia: 'middle' crocodiles

- Thalattosuchia: sea crocodiles

- Protosuchia: first crocodiles

Mesosuchia is a paraphyletic group as it does not include eusuchians (which nest within Mesosuchia). Mesoeucrocodylia was the name given to the clade that contains mesosuchians and eusuchians (Whetstone and Whybrow, 1983).

Phylogeny

Here is the consensus of Larsson & Sues (2007)[4] and Sereno et al. (2003):[5]

| Crocodylomorpha |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

The previous definitions of Crocodilia and Eusuchia do not accurately resemble the evolution of the group. The only order-level taxon that is currently considered valid is Crocodilia in the present definition. Prehistoric crocodiles are represented by many taxa, but since few major groups of the ancient forms are recognizable, a decision where to delimit new order-level clades is not yet possible. (Benson & Clark, 1988).

References

- ↑ Irmis, R. B.; Nesbitt, S. J.; Sues, H. -D. (2013). "Early Crocodylomorpha". Geological Society, London, Special Publications 379: 275. doi:10.1144/SP379.24.

- ↑ Martin, J.E. and Benton, M.J. (2008). "Crown Clades in Vertebrate Nomenclature: Correcting the Definition of Crocodylia." Systematic Biology, 57: 1,173 — 181.

- ↑ Parrilla-Bel, J.; Young, M. T.; Moreno-Azanza, M.; Canudo, J. I. (2013). Butler, Richard J, ed. "The First Metriorhynchid Crocodylomorph from the Middle Jurassic of Spain, with Implications for Evolution of the Subclade Rhacheosaurini". PLoS ONE 8: e54275. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054275.

- ↑ Larsson, Hans C. E.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (2007). "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Hamadasuchus rebouli (Crocodyliformes: Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Cretaceous of Morocco" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149 (4): 533–567. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00271.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ↑ Sereno, P. C.; Sidor, C. A.; Larsson, H. C. E.; Gado, B. (2003). "A new notosuchian from the Early Cretaceous of Niger" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23 (2): 477–482. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)023[0477:ANNFTE]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Benton, M. J. (2004), Vertebrate Palaeontology, 3rd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd

- Hay, O. P. 1930 (1929–1930). Second Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America. Carnegie Institution Publications, Washington, 1,990 pp.

External links

- Crocodylomorpha - webpages by Ross Elgin on the University of Bristol server

- Major subgroups classification (used here)

- Crocodylomorpha from Palaeos

- Crocodylomorpha - hyperlinked cladogram at Mikko's Phylogeny Archive

- Sereno, P. C. 2005. Stem Archosauria—TaxonSearch [version 1.0, 7 November 2005]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||