Cricket (insect)

| Cricket | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common black cricket (Gryllus assimilis ) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Superfamily: | Grylloidea |

| Family: | Gryllidae Bolívar, 1878 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

See Taxonomy section | |

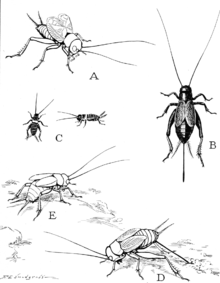

Crickets, family Gryllidae (also known as "true crickets"), are insects somewhat related to grasshoppers, and more closely related to katydids or bush crickets (family Tettigoniidae) and Weta (families Anostostomatidae and Rhaphidophoridae). They have somewhat flattened bodies and long antennae. There are more than 900 species of crickets.[1] They tend to be nocturnal[2] and are often confused with grasshoppers because they have a similar body structure including jumping hind legs. Crickets are not harmful to humans.

Cricket chirping

The sound emitted by crickets is commonly referred to as chirping; the scientific name is stridulation. Usually only the male crickets chirp, however some female crickets do as well. The sound is emitted by the stridulatory organ, a large vein running along the bottom of each wing, covered with "teeth" (serration) much like a comb. The chirping sound is created by running the top of one wing along the teeth at the bottom of the other wing. As the male cricket does this, he also holds the wings up and open, so that the wing membranes can act as acoustical sails. It is a popular myth that the cricket chirps by rubbing its legs together.

There are four types of cricket song: The calling song attracts females and repels other males, and is fairly loud. The courting song is used when a female cricket is near, and is a very quiet song. An aggressive song is triggered by chemoreceptors on the antennae that detect the near presence of another male cricket and a copulatory song is produced for a brief period after a successful mating.[3]

Crickets chirp at different rates depending on their species and the temperature of their environment. Most species chirp at higher rates the higher the temperature is (approximately 62 chirps a minute at 13 °C in one common species; each species has its own rate). The relationship between temperature and the rate of chirping is known as Dolbear's Law. According to this law, counting the number of chirps produced in 14 seconds by the snowy tree cricket common in the United States and adding 40 will approximately equal the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit.[4]

Crickets, like all other insects, are cold-blooded. They take on the temperature of their surroundings. Many characteristics of cold-blooded animals, like the rate at which crickets chirp, or the speed at which ants walk, follow an equation called the Arrhenius equation. This equation describes the activation energy or threshold energy required to induce a chemical reaction. For instance, crickets, like all other organisms, have many chemical reactions occurring within their bodies. As the temperature rises, it becomes easier to reach a certain activation or threshold energy, and chemical reactions, like those that occur during the muscle contractions used to produce chirping, happen more rapidly. As the temperature falls, the rate of chemical reactions inside the crickets' bodies slow down, causing characteristics, such as chirping, to also slow down.

Crickets have tympanic membranes located just below the middle joint of each front leg (or knee). This enables them to hear another cricket's song.

In 1975, Dr. William H. Cade discovered that the parasitic tachinid fly Ormia ochracea is attracted to the song of the male cricket, and uses it to locate the male in order to deposit her larvae on him. It was the first example of a natural enemy that locates its host or prey using the mating signal.[5] Since then, many species of crickets have been found to be carrying the same parasitic fly, or related species. In response to this selective pressure, a mutation leaving males unable to chirp was observed amongst a population of field crickets on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, giving these crickets the obvious advantage of eluding their parasitoid opponents.

Diet and life cycle

Crickets are omnivorous scavengers who feed on organic materials, including decaying plant material, fungi, and some seedling plants. Crickets eat their own dead when there are no other sources of food available, and exhibit predatorial behavior upon weakened, crippled crickets.

Crickets have relatively powerful jaws, and several species have been known to bite humans.[6]

Crickets mate in late summer and lay their eggs in autumn. The eggs hatch in the spring and have been estimated to number as high as 200 per fertile female. Species Acheta domestica however lays eggs almost continually, with the females capable of laying at least twice a month. Female crickets have a long needle-like egg-laying organ called an ovipositor.

Inbreeding avoidance

Female Teleogryllus oceanicus crickets from natural populations mate polyandrously and store sperm from multiple males.[7] Female crickets exert a post-copulatory fertilization bias in favor of unrelated males to avoid the genetic consequences of inbreeding. Fertilization bias depends on the control of sperm transport to the sperm storage organs. It appears that inhibition of sperm storage by female crickets can act as a form of cryptic female choice to avoid the severe negative effects of inbreeding.[8]

In controlled breeding experiments with the cricket Gryllus firmus, seven inbred lines were tested, and it was found that during 14 generations of brother–sister matings nymphal weight and early fecundity declined substantially.[9] This observed inbreeding depression appeared to be due to an increased frequency of homozygous combinations of deleterious recessive alleles generated by the inbreeding (thereby decreasing fitness).[9] These results support the general idea that the principal benefit of outcrossing is the masking of deleterious recessive alleles by wild-type alleles.[10] (Also see Complementation (genetics).)

Taxonomy

Subfamilies of the family Gryllidae:

- Eneopterinae – (true) bush crickets, not to be confused with the katydid family, in British English also called bush crickets

- Gryllinae – common or field crickets; brown or black; despite the name, some of them enter houses (e.g. Acheta domesticus, the house cricket). This family includes the genera Gryllus, Platygryllus, Acheta and Gryllodes.

- Nemobiinae – ground crickets

- Oecanthinae – tree crickets; usually green with broad, transparent wings; frequent trees and shrubs.

- Phalangopsinae - spider crickets

- Podoscirtinae – anomalous crickets

- Pteroplistinae

- Trigonidiinae – sword-tail crickets

In addition to the above subfamilies in the family Gryllidae, several other orthopteran groups outside of this family also may be called crickets:

- Cave crickets - also called camel crickets

- Jerusalem crickets / Sand crickets

- Mogoplistidae – scaly crickets

- Mole crickets

- Mormon crickets

- Myrmecophilidae – ant crickets

- Parktown prawns

- Tettigoniidae – katydids or bush crickets

Folklore and myths

The folklore and mythology surrounding crickets is extensive.[11] The singing of crickets in the folklore of Brazil and elsewhere is sometimes taken to be a sign of impending rain, or of a financial windfall. In Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca's chronicles of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, the sudden chirping of a cricket heralded the sighting of land for his crew, just as their water supply had run out.[12] In Caraguatatuba, Brazil, a black cricket in a room is said to portend illness; a gray one, money; and a green one, hope.[12] In Alagoas state, northeast Brazil, a cricket announces death, thus it is killed if it chirps in a house.[13] In the village of Capueiruçu in Bahia State, a constantly chirping cricket foretells pregnancy, but if it pauses, money is expected.[14] The mole cricket locally known as "paquinha", "jeguinho", "cachorrinho-d'água", or "cava-chão" (genera Scapteriscus and Neocurtilla, Gryllotalpidae) is said to predict rain when it digs into the ground.[15] In Barbados, a loud cricket means money is coming in; hence, a cricket must not be killed or evicted if it chirps inside a house. However, another type of cricket that is less noisy forebodes illness or death.[16] In Zambia, the Gryllotalpa africanus cricket is held to bring good fortune to anyone who sees it.[17]

Crickets are popular pets and are considered good luck in some countries; in China, crickets are sometimes kept in cages.[18] It is also common to have them as caged pets in some European countries, particularly in the Iberian Peninsula. Cricket fighting as a gambling or sports betting pastime also occurs, particularly in China, Mexico and Southeast Asia.

Consumption

Various species of crickets are a part of people's diets in some countries, and are considered delicacies of high cuisine in certain countries. In Cambodia, Thailand and the southern part of Vietnam, cricket is commonly eaten as a snack. It is prepared by deep frying the soaked and cleaned insect in oil. In the United States of America crickets can now be found in protein bars, baked goods, and protein powders.[19]

Crickets are popular as a live food source for carnivorous pets like frogs, lizards, tortoises, salamanders, wasps and spiders.

Feeding crickets with nutritious food in order to pass the nutrition onto animals that eat them is known as gut loading. In addition to this, the crickets are often dusted with a mineral supplement powder to ensure complete nutrition to the pet.

In popular culture

- Since the days of radio entertainment, the sound of crickets chirping has been used as an indication that a scene is taking place late at night. In comedy formats, the sound of crickets may be used to humorously indicate a dead silence when a response, such as laughter after a punch line, is expected.[20] Similarly, in online communication, writers may use the concept of "crickets chirping" in a rhetorical sense to signal that the writer believes that he or she has made a point that a hypothetical opponent cannot answer. The space that would have been occupied by the nonexistent answer is instead occupied by the symbolic word *crickets* or *chirp chirp* to symbolize this silence.

- The Walt Disney Company has used a number of notable cricket characters in their animated movies. In the 1940s Pinocchio, Jiminy Cricket becomes the title character's conscience, and in Mulan, Cri-kee is carried in a cage as a symbol of luck, as in many Asian countries.

- Chester Cricket is the main character in the children's book The Cricket In Times Square by George Selden, which was named a Newbery Honor Book in 1961.

- The Crickets was the name of the band of legendary rock and roll pioneer Buddy Holly. In Lubbock, Texas, Holly's home town, a baseball team in the Texas-Louisiana League were called the Lubbock Crickets. "Cricket" is also musician's slang for a harmonica. Van Morrison may be heard calling for the "cricket" in the studio version of "Bright Side of the Road", introducing the harmonica solo.

- Cricket is the name of a US children's literary magazine founded in 1973. Advanced concepts in the stories and poems are explained by a cast of insect and other small creatures drawn in the margins. The lead of these cartoon characters is Cricket, the magazine's namesake.

Gallery

-

Scanning electron micrograph of a spiracle valve—the organ that allows fresh air to pass into the cricket's respiratory system

-

Gryllus campestris - female juvenile form

-

A cricket

-

Two adult Acheta domestica crickets feeding

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Garber, Stephen (2013). The Urban Naturalist. Courier Dover Publications. p. 61. ISBN 0486148327

- ↑ University of Arizona, Cricket Info

- ↑

- ↑ Urban Legends Reference Pages: Cricket Chirp Thermometer

- ↑ Cade, W. H. 1975. Acoustically orienting parasitoids: Fly phonotaxis to cricket song. Science 190: 1312-1313.

- ↑ J.R.S.C. (1879). Journal of Horticulture and Practical Gardening, Volume 37, p.503.

- ↑ Simmons LW, Beveridge M. The strength of postcopularory sexual selection within natural populations of field crickets. Behav Ecol. 2010 21:1179-85. doi:10.1093/beheco/arg132

- ↑ Tuni C, Beveridge M, Simmons LW (2013). "Female crickets assess relatedness during mate guarding and bias storage of sperm towards unrelated males". J. Evol. Biol. 26 (6): 1261–8. doi:10.1111/jeb.12118. PMID 23745826.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Roff DA (2002). "Inbreeding depression: tests of the overdominance and partial dominance hypotheses". Evolution 56 (4): 768–75. PMID 12038534.

- ↑ Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science 229 (4719): 1277–81. PMID 3898363.

- ↑ "Cricket singing means rain: semiotic meaning of insects in the district of Pedra Branca, Bahia State, northeastern Brazil"

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lenko and Papavero 1996

- ↑ Araújo 1977

- ↑ K.L.G. Lima, unpublished data

- ↑ Fowler 1994

- ↑ Forde 1988

- ↑ Mbata 1999

- ↑ Carrera 1991

- ↑ http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/news/2014/12/cricket-flour-protein-bars-pass-the-taste-test/index.htm

- ↑ "Chirping Crickets" at TV Tropes

- Bibliography

- Gorochov, A.V. & Mostovski, M.B. 2008. Apterous crickets of the tribe Gryllini from South Africa and Namibia (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). African Invertebrates 49 (1): 109-121.

- Lisa Gail Ryan, Berthold Laufer, Lafcadio Hearn (1996). Insect musicians & cricket champions: a cultural history of singing insects in China and Japan. China Books. ISBN 0-8351-2576-9.

- Franz Huber, Thomas Edwin Moore, Werner Loher (1989). Cricket behavior and neurobiology. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2272-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gryllidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Gryllidae |

- The cricket suicide

- Intro on house crickets

- Singing Insects of North America An online field guide

- house cricket on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- tropical house cricket on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- field crickets, Gryllus spp. on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Web article: The recent evolution of a population of silent Hawaiian crickets WhyFiles.org

- "Tuning in to Cricket Radio", John Himmelman, Berfrois

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||