Cree language

| Cree | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Canada; United States: Montana |

| Ethnicity | Cree |

Native speakers |

120,000 (2006 census)[1] (including Montagnais–Naskapi and Atikamekw) |

|

Algic

| |

| Latin, Canadian Aboriginal syllabics (Cree) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

cr |

| ISO 639-2 |

cre |

| ISO 639-3 |

cre – inclusive codeIndividual codes: crk – Plains Cree cwd – Woods Cree csw – Swampy Cree crm – Moose Cree crl – Northern East Cree crj – Southern East Cree nsk – Naskapi moe – Montagnais atj – Atikamekw |

| Glottolog |

cree1271[3] |

|

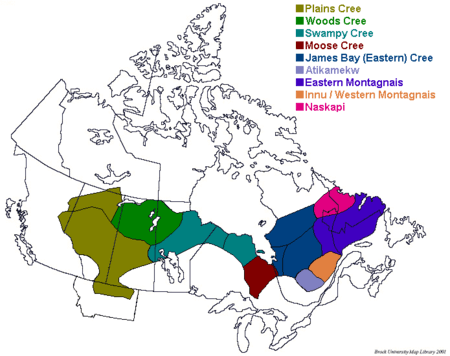

A rough map of Cree dialect areas | |

Cree /ˈkriː/[4] (also known as Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi) is an Algonquian language spoken by approximately 117,000 people across Canada, from the Northwest Territories and Alberta to Labrador, making it the aboriginal language with the highest number of speakers in Canada.[1] Despite numerous speakers within this wide-ranging area, the only region where Cree has any official status is in the Northwest Territories, alongside eight other aboriginal languages.[5]

Names

Endonyms are Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ (Plains Cree), Nīhithawīwin (Woods Cree), Nehirâmowin (Atikamekw), Nehlueun (Western Montagnais, Piyekwâkamî dialect), Ilnu-Aimûn (Western Montagnais, Betsiamites dialect), Innu-Aimûn (Eastern Montagnais), Iyiniu-Ayamiwin (Southern East Cree), Iyiyiu-Ayimiwin (Northern East Cree), Ililîmowin (Moose Cree), Ininîmowin (Eastern Swampy Cree), and nēhinawēwin (Western Swampy Cree).

Origin and diffusion

Cree is believed to have begun as a dialect of the Proto-Algonquian language spoken 2,500 to 3,000 years ago in the original Algonquian homeland, an undetermined area thought to be near the Great Lakes. The speakers of the proto-Cree language are thought to have moved north, and diverged rather quickly into two different groups on each side of James Bay, after which time, the eastern group began to diverge into separate dialects, whereas the western grouping probably broke into distinct dialects much later.[6] After this point it is very difficult to make definite statements about how different groups emerged and moved around, because there are no written works in the languages to compare, and descriptions by Europeans are not systematic; as well, Algonquian people have a tradition of bilingualism and even of outright adopting a new language from neighbours.[7]

A traditional view among 20th-century anthropologists and historians of the fur trade posits that the Western Woods Cree and the Plains Cree (and therefore their dialects) did not diverge from other Cree peoples before 1670 CE, when the Cree expanded out of their homeland near James Bay due to access to European firearms. By contrast, James Smith of the Museum of the American Indian stated in 1987 that the weight of archeological and linguistic evidence puts the Cree far west as the Peace River Region of Alberta before European contact.[8]

Dialect criteria

The Cree dialect continuum can be divided by many criteria. Dialects spoken in northern Ontario and the southern James Bay, Lanaudière, and Mauricie regions of Quebec make a distinct difference between /ʃ/ (sh as in she) and /s/, while those to the west (where both are pronounced /s/) and east (where both are pronounced either /ʃ/ or /h/) do not. In several dialects, including northern Plains Cree and Woods Cree, the long vowels /eː/ and /iː/ have merged into a single vowel, /iː/. In the Quebec communities of Chisasibi, Whapmagoostui, and Kawawachikamach, the long vowel /eː/ has merged with /aː/.

However, the most transparent phonological variation between different Cree dialects are the reflexes of Proto-Algonquian *l in the modern dialects, as shown below:

| Dialect | Location | Reflex of *l |

Word for "Native person" ← *elenyiwa |

Word for "You" ← *kīla |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plains Cree | SK, AB, BC, NT | y | iyiniw | kīya |

| Woods Cree | MB, SK | ð/th | iðiniw/ithiniw | kīða/kītha |

| Swampy Cree | ON, MB, SK | n | ininiw | kīna |

| Moose Cree | ON | l | ililiw | kīla |

| Atikamekw | QC | r | iriniw | kīr |

| Northern East Cree | QC | y | iyiyiw | čīy |

| Southern East Cree | QC | y | iyiyū/iyinū | čīy |

| Kawawachikamach Naskapi | QC | y | iyiyū | čīy |

| Western Innu | QC | l | ilnu | čīl |

| Eastern Innu | QC, NL | n | innu | čīn |

The Plains Cree, speakers of the y dialect, refer to their language as nēhiyawēwin, whereas Woods Cree speakers say nīhithawīwin, and Swampy Cree speakers say nēhinawēwin. This is similar to the alternation in the Siouan languages Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota.

Another important phonological variation among the Cree dialects involves the palatalisation of Proto-Algonquian *k: East of the Ontario-Quebec border (except for Atikamekw), Proto-Algonquian *k has changed into /tʃ/ or /ts/ before front vowels. See the table above for examples in the *kīla column.

Very often the Cree dialect continuum is divided into two languages: Cree and Montagnais. Cree includes all dialects which have not undergone the *k > /tʃ/ sound change (BC–QC) while Montagnais encompasses the territory where this sound change has occurred (QC–NL). These labels are very useful from a linguistic perspective but are confusing as East Cree then qualifies as Montagnais. For practical purposes, Cree usually covers the dialects which use syllabics as their orthography (including Atikamekw but excluding Kawawachikamach Naskapi), the term Montagnais then applies to those dialects using the Latin script (excluding Atikamekw and including Kawawachikamach Naskapi). The term Naskapi typically refers to Kawawachikamach (y-dialect) and Natuashish (n-dialect).

Dialect groups

The Cree dialects can be broadly classified into nine groups. From west to east:

| ISO-3 code and name | Linguasphere code and name[9] | Moseley[10] | dialect type | additional comments | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *l | *k(i) | *š | *ē | ||||||||||

| cre Cree (generic) | crk Plains Cree | 62-ADA-a Cree | 62-ADA-aa Plains Cree | Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi | Western Cree | Plains Cree | y | k | s | ē | (southern) | Divided to Southern Plains Cree (Nēhiyawēwin) and Northern Plains Cree (Nīhiyawīwin or Nīhiyawīmowin). In the Northern dialect, ē has merged into ī. | |

| y | k | s | ī | (northern) | |||||||||

| cwd Woods Cree (Nīhithawīwin) | 62-ADA-ab Woods Cree | Wood Cree | th | k | s | ī | In this dialect ē has merged into ī. | ||||||

| (r)\th | k | s | ī | Missinipi Cree (Nīhirawīwin). Also known as "Rocky Cree". Historical r have transitioned to th and have merged into Woods Cree. While Woods Cree proper have hk, Missinipi Cree have sk, e.g., Woods Cree mihkosiw v. Missinipi Cree miskosiw : "he/she is red". | |||||||||

| csw Swampy Cree (Nēhinawēwin) | 62-ADA-ac Swampy Cree, West (Ininīmowin) | Swampy Cree | n | k | s | ē | Eastern Swampy Cree, together with Moose Cree, also known as "West Main Cree," "Central Cree," or "West Shore Cree." In the western dialect, š has merged with s. Western Swampy Cree also known as "York Cree;" together with Northern Plains Cree and Woods Cree, also known as "Western Woodland Cree." | ||||||

| 62-ADA-ad Swampy Cree, East (Ininiwi-Išikišwēwin) | n | k | š | ē | |||||||||

| crm Moose Cree (Ililīmowin) | 62-ADA-ae Moose Cree | Moose Cree | n\l | k | š | ē | (upland) | Together with the Eastern Swampy Cree, also known as "West Main Cree," "Central Cree," or "West Shore Cree." In Swampy Cree influenced areas, some speakers use n instead of l, e.g., upland Moose Cree iliniw v. lowland Moose Cree ililiw : "human". | |||||

| l | k | š | ē | (lowland) | |||||||||

| crl Northern East Cree (Īyyū Ayimūn) | 62-ADA-af Cree, East | Eastern Cree | East Cree | y | k\č | š | ā | Also known as "James Bay Cree" or "East Main Cree". The long vowels ē and ā have merged in the northern dialect but are distinct in the southern. Southern East Cree is divided between coastal (southwestern) and inland (southeastern) varieties. Also, the inland southern dialect has lost the distinction between s and š. Here, the inland southern dialect falls in line with the rest of the Naskapi groups where both phonemes have become š. Nonetheless, the people from the two areas easily communicate. In the northern dialect, ki is found in situations were short unaccented vowel a transitioned to i without changing the k to č. | |||||

| crj Southern East Cree (Īynū Ayimūn) | 62-ADA-ag Cree, Southeast | y | č | š | ē | (coastal) | |||||||

| y | č | š~s | ē | (inland) | |||||||||

| nsk Naskapi | 62-ADA-b Innu | 62-ADA-ba Mushau Innuts | 62-ADA-baa Koksoak | Naskapi | y | č | š~s | ā | Western Naskapi (Kawawachikamach) | ||||

| 62-ADA-bab Davis Inlet | n | č | š~s | ā | Eastern Naskapi (Mushuau Innu or Natuashish) | ||||||||

| moe Montagnais | 62-ADA-bb Uashau Innuts + Bersimis | 62-ADA-bbe Pointe Bleue | Montagnais | l | č | š | ē | Western Montagnais (Lehlueun); also known as the "Betsiamites dialect" | |||||

| 62-ADA-bbd Escoumains | |||||||||||||

| 62-ADA-bbc Bersimis | |||||||||||||

| 62-ADA-bbb Uashaui Innuts | n | č | š | ē | Western Montagnais (Nehlueun), but sometimes called "Central Montagnais" or "Piyekwâkamî dialect" | ||||||||

| 62-ADA-bba Mingan | n | č | š | ē | Eastern Montagnais (Innu-aimûn) | ||||||||

| atj Atikamekw (Nehirâmowin) | 62-ADA-c Atikamekw | 62-ADA-ca Manawan | Western Cree (cont'd) | Attikamek | r | k | š | ē | |||||

| 62-ADA-cb Wemotaci | |||||||||||||

| 62-ADA-cc Opitciwan | |||||||||||||

Phonology

This table is made to show all possible consonant phonemes that may be included in a Cree language.

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Stop | p | t | t͡s | t͡ʃ | k | ||

| Fricative | ð | s | ʃ | h | |||

| Approximant | ɹ | j | w | ||||

| Lateral | l |

Syntax

Like many Native American languages, Cree features a complex polysynthetic morphology and syntax. A common grammatical feature in Cree dialects, in terms of sentence structure, is non-regulated word order. Word order is not governed by a specific set of rules or structure; instead, “subjects and objects are expressed by means of inflection on the verb”.[11] Subject, Verb, and Object (SVO) in a sentence can vary in order, for example, SVO, VOS, OVS, and SOV.[11][12]

Obviation is also a key aspect of the Cree language(s). In a sense, the obviative can be defined as any third-person ranked lower on a hierarchy of discourse salience than some other (proximate) discourse-participant. “Obviative animate nouns, [in the Plains Cree dialect for instance], are marked by [a suffix] ending –a, and are used to refer to third persons who are more peripheral in the discourse than the proximate third person”.[13] For example:

- Sam wâpam-ew Susan-a

- Sam see-3SG Susan-3OBV

- "Sam sees Susan"

The suffix -a marks Susan as the obviative, or ‘fourth’ person, the person furthest away from the discourse.[11]

Another distinct feature of the Cree language is what could be understood as gender, similar to the French language’s genders of male and female nouns. Cree defines nouns as being animate or inanimate. There is no distinct rule governing the classification of animacy or inanimacy, rather, it is learned through immersive language acquisition.[11] A Cree word can be very long, and express something that takes a series of words in English. For example, the Plains Cree word for "school" is kiskinohamātowikamikw, "know.CAUS.APPLICATIVE.RECIPROCAL.place" or the "knowing-it-together-by-example place".

Written Cree

Writing systems

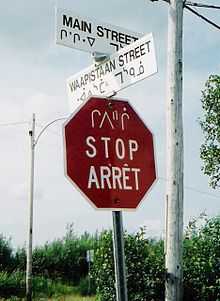

Cree dialects, except for those spoken in eastern Quebec and Labrador, are traditionally written using Cree syllabics, a variant of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics, but can be written with the Latin script as well. Both writing systems represent the language phonetically. Cree is always written from left to right horizontally.[14] The easternmost dialects are written using the Latin script exclusively. The dialects of Plains Cree, Woods Cree, and Swampy Cree use Western Cree syllabics and the dialects of East Cree, Moose Cree, and Naskapi use Eastern Cree syllabics. In this syllabic system, each symbol, which represents a consonant, can be written four ways, each direction representing its corresponding vowel.[14] Some dialects of Cree have up to seven vowels, so additional diacritics are placed after the syllabic to represent the corresponding vowels. Finals represent stand-alone consonants.[14]

The following tables show the syllabaries of Eastern and Western Cree dialects, respectively:

| Eastern Cree syllabary | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Vowels | Final | ||||||

| ê | i | o | a | î | ô | â | ||

| ᐁ | ᐃ | ᐅ | ᐊ | ᐄ | ᐆ | ᐋ | ||

| p | ᐯ | ᐱ | ᐳ | ᐸ | ᐲ | ᐴ | ᐹ | ᑉ |

| t | ᑌ | ᑎ | ᑐ | ᑕ | ᑏ | ᑑ | ᑖ | ᑦ |

| k | ᑫ | ᑭ | ᑯ | ᑲ | ᑮ | ᑰ | ᑳ | ᒃ |

| c | ᒉ | ᒋ | ᒍ | ᒐ | ᒌ | ᒎ | ᒑ | ᒡ |

| m | ᒣ | ᒥ | ᒧ | ᒪ | ᒦ | ᒨ | ᒫ | ᒻ |

| n | ᓀ | ᓂ | ᓄ | ᓇ | ᓃ | ᓅ | ᓈ | ᓐ |

| s | ᓭ | ᓯ | ᓱ | ᓴ | ᓰ | ᓲ | ᓵ | ᔅ |

| sh | ᔐ | ᔑ | ᔓ | ᔕ | ᔒ | ᔔ | ᔖ | ᔥ |

| y | ᔦ | ᔨ | ᔪ | ᔭ | ᔩ | ᔫ | ᔮ | ᔾ (ᐤ) |

| r | ᕃ | ᕆ | ᕈ | ᕋ | ᕇ | ᕉ | ᕌ | ᕐ |

| l | ᓓ | ᓕ | ᓗ | ᓚ | ᓖ | ᓘ | ᓛ | ᓪ |

| v, f | ᕓ | ᕕ | ᕗ | ᕙ | ᕖ | ᕘ | ᕚ | ᕝ |

| th* | ᕞ | ᕠ | ᕤ | ᕦ | ᕢ | ᕥ | ᕧ | ᕪ |

| w | ᐌ | ᐎ | ᐒ | ᐗ | ᐐ | ᐔ | ᐙ | ᐤ |

| h | ᐦᐁ | ᐦᐃ | ᐦᐅ | ᐦᐊ | ᐦᐄ | ᐦᐆ | ᐦᐋ | ᐦ |

| Western Cree syllabary | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Vowels | Final | ||||||

| ê | i | o | a | î | ô | â | ||

| ᐁ | ᐃ | ᐅ | ᐊ | ᐄ | ᐆ | ᐋ | ||

| p | ᐯ | ᐱ | ᐳ | ᐸ | ᐲ | ᐴ | ᐹ | ᑊ |

| t | ᑌ | ᑎ | ᑐ | ᑕ | ᑏ | ᑑ | ᑖ | ᐟ |

| k | ᑫ | ᑭ | ᑯ | ᑲ | ᑮ | ᑰ | ᑳ | ᐠ |

| c | ᒉ | ᒋ | ᒍ | ᒐ | ᒌ | ᒎ | ᒑ | ᐨ |

| m | ᒣ | ᒥ | ᒧ | ᒪ | ᒦ | ᒨ | ᒫ | ᒼ |

| n | ᓀ | ᓂ | ᓄ | ᓇ | ᓃ | ᓅ | ᓈ | ᐣ |

| s | ᓭ | ᓯ | ᓱ | ᓴ | ᓰ | ᓲ | ᓵ | ᐢ |

| y | ᔦ | ᔨ | ᔪ | ᔭ | ᔩ | ᔫ | ᔮ | ᐩ (ᐝ) |

| th | ᖧ | ᖨ | ᖪ | ᖬ | ᖩ | ᖫ | ᖭ | ‡ |

| w | ᐍ | ᐏ | ᐓ | ᐘ | ᐑ | ᐕ | ᐚ | ᐤ |

| h | ᐦᐁ | ᐦᐃ | ᐦᐅ | ᐦᐊ | ᐦᐄ | ᐦᐆ | ᐦᐋ | ᐦ |

| hk | ᕽ | |||||||

| l | | |||||||

| r | | |||||||

Speakers of various Cree dialects have begun creating dictionaries to serve their communities. Some projects, such as the Cree Language Resource Project (CLRP), are developing an online bilingual Cree dictionary for the Cree language.

Punctuation

Cree does not use the period (.) at the end of sentences when syllabics are used. Instead, either a full-stop glyph (᙮) or a double m-width space is used between words to signal the transition from one sentence to the next. In addition, Cree does not use the question mark (?). For instance, in the Plains Cree dialect, to indicate a question, the suffix -cî can be included in the sentence:[11]

- John cî kîmîcisow

- 3rd person sing--interrogative marker--past tense marker--verb--3rd person suffix

- Did John eat?

Additionally, interrogatives (where, when, what, why, who) can be used.[11]

Contact languages

Cree is also a component language in two contact languages, Michif and Bungi. Both languages were spoken by members of the Métis, the Voyageurs, and European settlers of Western Canada and parts of the Northern United States.

Michif is a mixed language which combines Cree with French. For the most part, Michif uses Cree verbs, question words, and demonstratives while using French nouns. Michif is unique to the Canadian prairie provinces as well as to North Dakota and Montana in the United States.[15] Michif is still spoken in central Canada and in North Dakota.

Bungi is a dialect of Scottish English with substrate influences from Cree and Ojibwe.[16] Some French words have also been incorporated into its lexicon. This language flourished at and around the Red River Settlement (modern day location of Winnipeg, Manitoba) by the mid to late 1800s.[17] Bungi is now virtually extinct.[16]

Many Cree words also became the basis for words in the Chinook Jargon trade language used until some point after contact with Europeans.

Cree has also been incorporated into two other mixed languages within Canada. The Oji-Cree language (also Severn Ojibwe), spoken in parts of Manitoba and western Ontario, is a mixed language of Cree and Ojibwe, and the Nehipwat language, which is a blending of Cree with Assiniboine. Nehipwat is found only in a few southern Saskatchewan reserves and is now nearing extinction. Nothing is known of its structure.[18]

Legal status

The social and legal status of Cree varies across Canada. Cree is one of the eleven official languages of the Northwest Territories, but is only spoken by a small number of people there in the area around the town of Fort Smith.[5] It is also one of two principal languages of the new regional government of Eeyou Istchee/Baie-James Territory in Northern Quebec, the other being French.[19]

Study and teaching

In many areas, Cree is a vibrant community language spoken by large majorities and taught in schools through immersion and second-language programmes. In other areas, its use has declined dramatically. Cree is one of the least endangered aboriginal languages in North America, but is nonetheless at risk since it possesses little institutional support in most areas.

In 2013, free Cree language electronic books for beginners became available for Alberta language teachers.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Statistics Canada: 2006 Census

- ↑ Official Languages of the Northwest Territories (map)

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Northwest Territories Official Languages Act, 1988 (as amended 1988, 1991–1992, 2003)

- ↑ Rhodes and Todd, "Subarctic Algonquian Languages" in Handbook of North American Indians: Subarctic, p. 60

- ↑ Rhodes and Todd, 60-61

- ↑ Smith, James G. E. (August 1987). "The Western Woods Cree: Anthropological Myth and Historical Reality". American Ethnologist 14 (3): 434–48. doi:10.1525/ae.1987.14.3.02a00020.

The weight of evidence now indicates that the Cree were as far west as the Peace River long before the advent of the European fur traders, and that post-contact social organization was not drastically affected by the onset of the fur trade.

- ↑ Linguasphere code 62-ADA is called "Cree+Ojibwa net", listing four divisions of which three are shown here—the fourth division 62-ADA-d representing the Ojibwe dialects, listed as "Ojibwa+ Anissinapek".

- ↑ Moseley, Christopher. 2007. Encyclopedia of World's Endangered Languages. ISBN 0-203-64565-0

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Thunder,Dorothy

- ↑ Dahlstrom, introduction

- ↑ Dahlstrom pp. 11

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Ager, Simon: Omniglot, Cree Syllabary

- ↑ Bakker and Papen p. 295

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bakker and Papen p. 304

- ↑ Carter p. 63

- ↑ Bakker and Papen p. 305

- ↑ Agreement on Governance in the Eeyou Istchee James Bay Territory Between the Crees of Eeyou Istchee and the Gouvernement du Québec, 2012

- ↑ Betowski, Bev. "E-books show kids the colour of Cree language". University of Alberta News & Events. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

Bibliography

- Ahenakew, Freda, Cree Language Structures: A Cree Approach. Pemmican Publications Inc., 1987. ISBN 0-919143-42-3

- Bakker, Peter and Robert A. Papen. “Michif: A Mixed Language based on French and Cree”. Contact Languages: A Wider Perspective. Ed. Sarah G. Thomason. 17 vols. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Co. 1997. ISBN 1-55619-172-3.

- Bloomfield, Leonard. Plains Cree Texts. New York: AMS Press, 1974. ISBN 0-404-58166-8

- Carter, Sarah. Aboriginal People and Colonizers of Western Canada to 1900. University of Toronto Press Inc. Toronto: 1999. ISBN 0-8020-7995-4.

- Castel, Robert J., and David Westfall. Castel's English–Cree Dictionary and Memoirs of the Elders Based on the Woods Cree of Pukatawagan, Manitoba. Brandon, Man: Brandon University Northern Teacher Education Program, 2001. ISBN 0-9689858-0-7

- Dahlstrom, Amy. Plains Cree Morphosyntax. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Garland Pub, 1991. ISBN 0-8153-0172-3

- Ellis, C. D. Spoken Cree, Level I, west coast of James Bay. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2000. ISBN 0-88864-347-0

- Hirose, Tomio. Origins of predicates evidence from Plains Cree. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0-415-96779-1

- Junker, Marie-Odile, Marguerite MacKenzie, Luci Salt, Alice Duff, Daisy Moar & Ruth Salt (réds) (2007–2008) Le Dictionnaire du cri de l'Est de la Baie James sur la toile: français-cri et cri-français (dialectes du Sud et du Nord).

- LeClaire, Nancy, George Cardinal, Earle H. Waugh, and Emily Hunter. Alberta Elders' Cree Dictionary = Alperta Ohci Kehtehayak Nehiyaw Otwestamakewasinahikan. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1998. ISBN 0-88864-309-8

- MacKenzie, Marguerite, Marie-Odile Junker, Luci Salt, Elsie Duff, Daisy Moar, Ruth Salt, Ella Neeposh & Bill Jancewicz (eds) (2004–2008) The Eastern James Bay Cree Dictionary on the Web : English-Cree and Cree-English (Northern and Southern dialect).

- Steller, Lea-Katharina (née Virághalmy): Alkalmazkodni és újat adni – avagy „accomodatio“ a paleográfiában In: Paleográfiai kalandozások. Szentendre, 1995. ISBN 963-450-922-3

- Wolfart, H. Christoph. Plains Cree A Grammatical Study. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, new ser., v. 63, pt. 5. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1973. ISBN 0-87169-635-5

- Wolfart, H. C. & Freda Ahenakew, The Student's Dictionary of Literary Plains Cree. Memoir 15, Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics, 1998. ISBN 0-921064-15-2

- Wolvengrey, Arok, ed. nēhiýawēwin: itwēwina / Cree: Words / ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ: ᐃᑗᐏᓇ [includes Latin orthography and Cree syllabics]. [Cree–English English–Cree Dictionary – Volume 1: Cree-English; Volume 2: English-Cree]. Canadian Plains Research Center, 15 October 2001. ISBN 0-88977-127-8

External links

| Cree edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- The Cree-Innu linguistic atlas

- The Cree-Innu linguistic atlas, .pdf

- The Gift of Language and Culture website

- Our Languages: Cree (Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre)

- Languagegeek: Cree—OpenType font repository of aboriginal languages (including Cree).

- CBC Digital Archives—Eeyou Istchee: Land of the Cree

- Path of the Elders – Explore Treaty 9, Aboriginal Cree & First Nations history.

Lessons

Dictionaries

- On-line Eastern James Bay Cree dictionary (covers both Northern and Southern dialects)

- On-line Cree dictionary

- Wasaho Ininiwimowin (Wasaho Cree) Dictionary at Kwayaciiwin Education Resource Centre

E-books

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||