Craven

| Craven | ||

|---|---|---|

| Non-metropolitan district | ||

|

View of south Settle from Castlebergh | ||

| ||

Shown within North Yorkshire | ||

| Coordinates: 53°57′N 2°01′W / 53.95°N 2.02°W | ||

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | |

| Constituent country | England | |

| Region | Yorkshire and the Humber | |

| Ceremonial county | North Yorkshire | |

| Admin. HQ | Skipton | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Craven District Council | |

| • Leadership: | Alternative - Sec.31 | |

| • Executive: | Conservative | |

| • MPs: | Julian Smith | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 454 sq mi (1,177 km2) | |

| Area rank | 18th | |

| Population (2011 est.) | ||

| • Total | 55,500 | |

| • Rank | Ranked 315th | |

| • Density | 120/sq mi (47/km2) | |

| Time zone | Greenwich Mean Time (UTC+0) | |

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time (UTC+1) | |

| ONS code |

36UB (ONS) E07000163 (GSS) | |

| Ethnicity |

96.1% White 2.0% S.Asian[1] | |

| Website | cravendc.gov.uk | |

Craven is a local government district of North Yorkshire, England centred on the market town of Skipton. In 1974, Craven district was formed as the merger of Skipton urban district, Settle Rural District and most of Skipton Rural District, all in the West Riding of Yorkshire. It comprises the upper reaches of Airedale, Wharfedale, Ribblesdale, and includes most of the Aire Gap and Craven Basin.

The name Craven is much older than the modern district, and encompassed a larger area. This history is also reflected in the way the term is still commonly used, for example by the Church of England.

History

Craven: “The exact extent of it we nowhere find”

Craven has been the name of this district throughout recorded history.[3] Its extent in the 11th century can be deduced from The Domesday Book but its boundaries now differ according to whether considering administration, taxation or religion.[4]

Etymology

The derivation of the name Craven is uncertain, yet a Celtic origin related to the word for garlic (craf in Welsh) has been suggested[5] as has the proto-Celtic *krab- suggesting scratched or scraped in some sense[6] and even an alleged pre-Celtic word cravona, supposed to mean a stony region.[7] In civic use the name Craven or Cravenshire had given way to that of Staincliffe before 1166 yet the Archdeaconry remained Craven throughout.[8]

Prehistory

The first datable evidence of human life in Craven is ca 9000 BC: a hunter's harpoon point carved out of an antler found in Victoria Cave. Most traces of the Mesolithic nomadic hunters are the flint barbs they set into shafts. Extensive finds of these microliths lie around Malham Tarn and Semerwater. Flint does not occur in the Dales, the nearest outcrop is in East Yorkshire. On higher ground microliths are found near springs at the tree line at 500 m (1,600 ft) indicating campsites close to the open hunting grounds. The valley woodlands were inhabited by deer, boar and aurochs, the higher ground was open grassland that fed herds of reindeer, elk and horse. No permanent settlements have been found of that age, hunting here was seasonal, returning to the plains in winter.[9]

After 5000 BC long-distance trade is indicated by the distribution of stone axes. Lithic analysis can identify their quarry source as Langdale in central Cumbria and most finds are in Ribblesdale and Airedale indicating that Craven was their trade route through the Pennines.[9]

Neolithic farmers permanently settled in Craven, bringing domesticated livestock and used those stone axes to clear woodlands, probably by slash-and-burn, to increase areas for grazing[9] and crops.

Roman occupation

In the first century the Romans, having trouble controlling the Brigantes in the Yorkshire Dales, built forts at strategic points. In Craven one fort, possibly named Olenacum,[10] is at Elslack 53°56′27″N 2°06′58″W / 53.94078°N 2.1160°W.[11] Through this fort passes a Roman road linking two other forts: Bremetennacum at Ribchester Lancashire and another at Ilkley Yorkshire. Archaeologists describe the road as running north-east up Ribblesdale about 0.6 miles (1 km) east of Clitheroe, then bending eastwards near 53°53′35″N 2°20′29″W / 53.893°N 2.3413°W, then about 0.6 miles (1 km) north of Barnoldswick to pass into Airedale through the low 144 m (472 ft) pass near Thornton-in-Craven.[12][13]

Anglo-Saxon

To collect the Danegeld in 991–1016 the Anglo-Saxons divided their territory into tax districts. The Wapentakes of Staincliffe and Ewcross covered the region we call Craven but also areas beyond it such as the Forest of Bowland in Lancashire; and Sedbergh in Cumbria to the North.[14] The Church was still using these areas in the 16th century.

Norman Conquest

The farmlands were progressively taken from the Anglo-Scandinavian farmers and given by the King to selected Normans. The previous and subsequent landowners were recorded in the Domesday Book along with the area of the ploughland.

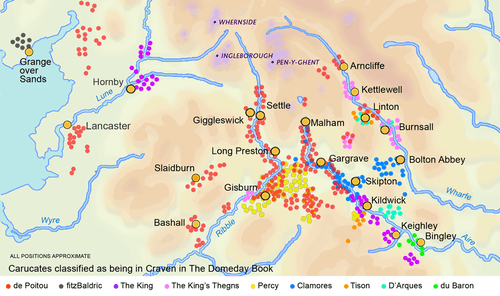

The Domesday Book

The Great Domesday Book[15][16] of 1086 did not use the later Wapentake district names in this part of England, as it usually did, but instead used the name Craven. The Book included lands further west than any later description: Melling, Wennington and Hornby[17] on the River Lune in Lonsdale and even Holker near Grange over Sands in Cumbria.

The historic northwestern boundary of Craven is much disputed. One faction declares that before the Norman Conquest the North of England from coast to coast was administered from York and named The Kingdom of York. By 1086 the Normans had designated only one county in the North of England and that was Yorkshire. One may assume thereby that the Norman Yorkshire of 1086 was much the same as the Kingdom of York of 1065; and the Domesday Book supports this. However the opposing faction proposes that the first Yorkshire was smaller, much as it was up till 1974, and that Amounderness, Cartmel, Furness, Kendale, Copeland and Lonsdale were attached to it in the Domesday Book merely for administrative convenience.[18][19][20][21]

Also the Domesday Book does not describe the width of Craven at all, for only arable land was noted. Ploughing is a minor part of Craven agriculture, and cultivators then had been reduced by the Harrying of the North. Most of Craven is uncultivable moorland and the valley bottoms are usually boggy, shady frost-hollows, with soils of glacial boulder clay very heavy to plough. So ploughing was limited to well-drained moderate slopes. The higher slopes are so full of rock debris that grazing oxen is still the primary living in Craven, with some sheep marginal.[22] Because grazing land was not tallied in the Domesday Book the full areas of the estates of the manors can only be induced[16]

The areas of ploughland were counted in carucates and oxgangs: one carrucate being eight oxgangs and one oxgang varying from fifteen to twenty acres. This vagueness comes from an oxgang signifying the land one ox could plough and that varied with the heaviness of the local soil. A carucate was the area that could be managed with team of eight oxen.

In 1086 Roger of Poitou was Tenant-in-chief of the western side of Craven: Ribblesdale and the Pendle valley.[23] In 1092 he was granted also Lonsdale to defend Morecambe Bay against Scottish raiding parties.

Soon after Henry I of England's succession to the crown in 1100 arose a rebellion of men with a variety of grievances. Several Yorkshire lords were involved and suffered confiscation of their estates. In Craven these were Roger the Poitevin, Erneis of Burun and Gilbert Tison. The King conducted a reorganization of Yorkshire by establishing men more skilled in government. Shortly after 1102 the castleries in Cravenshire were divided between the House of Romille and the House of Percy. The King was clearly intent that Cravenshire should retain a compact structure for he added-in estates from his own demesne. The result was two partially interwoven castleries incorporating nearly all the land in Craven. The Percy estates were mainly concentrated in Ribble Valley with their castle at Gisburn while the Romilles dominated upper Wharfedale and upper Airedale with their fortress at Skipton Castle.[24]

14th century

Craven was still suffering from Scottish raiders for example in 1318 they severely damaged churches as far south as Kildwick.[25]

In 1377, in the form of Poll Tax records, the earliest surviving detailed statistics of Craven were collected. From them we can compare the income brackets of various occupations, and the relative worth of villages.[26] The records list every hamlet and village using the wapentake system.[27] The Wapentakes of Staincliffe and Ewcross cover Craven but also areas beyond such as Sedburgh to the North. Young King Richard II had commanded that poll tax to pay off the debts he'd inherited from the Hundred Years' War. Its first application in 1377 was a flat rate and the second of 1379 was a sliding scale from 1 groat (4p pence) to 4 marks. But the third tax of 1381 of 4 groats (1 shilling) and up was applied corruptly and led to the Great Rising of 1381.

16th century

The Deanery of Craven had similar boundaries to the Wapentake of Staincliffe and so included the following areas which are not in the modern secular district of Craven:

- A large part of what is now the City of Bradford, namely the parishes Keighley, Addingham, and the Silsden and Steeton with Eastburn parts of the parish of Kildwick. However all of Bingley and part of Ilkley, though never part of Staincliffe Wapentake, were within Craven and are also now within Bradford. (They were in the upper division of the Wapentake of Skyrack.)

- The northern section of the modern Lancashire District of Ribble Valley, including Gisburn in Craven, and the Bowland Forest parishes of Bolton by Bowland, Slaidburn and Great Mitton, the latter including Waddington, West Bradford, and Grindleton. (Sawley, while not technically in the old Deanery, is also in this geographical area.)

- The north-eastern section of the modern Lancashire District of Pendle, including Barnoldswick, Bracewell, and the part of the old parish of Thornton in Craven which includes Earby and Kelbrook

17th century hearth tax

These valuable records also define the area by wapentakes. This tax was introduced by the government of Charles II at a time of serious fiscal emergency, and collection continued until repealed by William and Mary in 1689. Under its terms each liable householder was to pay one shilling for each hearth within their property, due twice annually at the equinoxes, Michaelmas (29 September) and Lady Day (25 March). The Yorkshire records of all three ridings are now completely transcribed, analyzed and available free online[28]

History of agriculture

Sheep

The hills and slopes of Craven are greatly involved in the history of sheep particularly in the history of wool. After 5000 BC the Neolothic farming movement introduced domesticated sheep,[9]:19 but the Roman occupation of Britain introduced advanced sheep husbandry to Britain and made wool into a national industry. Craven was made accessible by major roads from Ribchester up Ribblesdale and from York through Ilkley. The extent of a Roman villa farm excavated at Gargrave implies it practiced grazing on nearby moorland.[9]:39 By 1000 AD England and Spain were recognized as the pinnacles of European sheep wool production. About 1200 AD scientific treatises on agricultural estate management began to circulate amongst the Cistercian monasteries in the Yorkshire dales. These indicated the way to greatest profit was to produce wool for export.[29]

“The famous monasteries under the steep, wooded banks of Yorkshire dales began the movement that in the course of four or five hundred years converted most of North England and Scotland from unused wilderness into sheep-run.”

Fountains Abbey strongly affected Craven in upper Wharfedale, Airedale and Littondale. In 1200 the Abbey owned 15,000 sheep in various locations and traded directly with Italian merchants. On the limestone fells it held extensive sheep runs managed by granges located at valley heads to access both the moors and the rough pasture of valley sides. Many granges developed into hamlets. The Fountains’ sheep administrative centre was at Outgang Hill, Kilnsey.[9]:60 By 1320 Bolton Priory’s flock at Malham was about 2,750 and it built extensive sheep farm buildings there. Accounts show that a quarter of its cheese was sheep’s cheese, and that most of the Priory’s came from wool sales.[9]:71 It also developed fulling, sorting and grading into industries.[9]:95 Feudal Lords began to imitate monastic management methods for their own estates[29]:95 and in 1350 when the Black Death killed-off half the rent-paying farmers they had the bailiffs substitute sheep-pasture for tillage. The export of wool to the Flanders looms, and the concurrent growth of cloth manufacture in England, aided by Edward III's importation of Flemish weavers to teach his people the higher skill of the craft, made demand for all the wool that English flocks could supply.[29]:314 As the profitability of wool further increased some landowners converted all arable land into sheep pasture by evicting whole villages. Over 370 deserted medieval villages have been unearthed in Yorkshire.[30][30]:146 Henry VIII in 1539 suppressed the Monasteries and sold Littondale and the Bolton Priory's estates in lower Wharefedale and Airedale to Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland and Lord of Skipton.[9]:61 By 1600 the wool trade was the primary source of tax revenue for Queen Elizabeth I. Britain’s success made it a major influence in the development and spread of sheep husbandry worldwide.

In more modern times the Industrial Revolution brought factory production of wool cloth to towns further down Airedale and many Craven families, made redundant by agricultural machinery, moved south to work in the worsted mills. However in 1966 the price of wool fell by 40% due to the increased popularity of synthetic fibres. Farmers complain it now costs more to shear a sheep than you can get for its wool and the result is reduced flocks. Although the tough wool of hill sheep is still used for carpet weaving, sheep breeding is now mostly for lambs to sell on for fattening for meat in low pastures.[31]:25

Forestry

Woodlands are an important component of the landscape and are crucial to scenic beauty. The small surviving areas of ancient woodland have high biodiversity value. However the Pennines are now notably lacking in trees despite archaeological evidence showing 90% was woodlands before human settlement. Palynology indicates the decline in trees coincided with the increase in grasses in Neolithic times caused by direct clearance for pasture and by overgrazing.

Since sheep are grazers not browsers they do not affect mature trees however they devour all their seedlings. With a much narrower face than cattle they crop plants very close to the ground and with continuous grazing can overgraze land rapidly. Ancient Common Grazing rights made it impossible to actively grow trees, even for fuel, because coppicing requires enclosure to protect re-growth from sheep.[9]:94

From 2002 to 2008 a Yorkshire Dales National Park program encouraged sheep farmers to switch uplands livestock from sheep to cattle since they do not graze so intensively. Traditional breeds such as Blue Greys and Belted Galloways can survive the harsh winters and live off the rough grasses just as well a sheep.[32] Until December 2013 The National Park Farming and Forestry Improvement Scheme is offering grants to help farming, forestry and horticultural businesses become more efficient, more profitable and resilient whilst reducing the impact of farming on the environment.[33]

Since 1968 some moorland has been reforested by the Forestry Commission.[30]:132 Since 2005 the collection of indigenous seeds and propagation produced saplings for planting schemes that began in 2010. Between 2007 and 2013 The Dales Woodland Restoration Programme[34] funded the creation of 450 hectares of new native woodland, almost all on privately owned land.[35]

Cattle

In the 16th and 17th centuries Longhorn cattle prevailed in Craven. Good quality bulls were bought communally to improve the livestock on the common land beside each village. In the 18th century they crossbred with Shorthorns; fully grown crossbreeds weighed 420–560 pounds.

Some graziers of the Craven highlands also visited Scotland, for example Oban, Lanark and Stirling, to purchase stock to be brought down the drove roads to the cattle-rearing district. In the summer of 1745 the celebrated Mr Birtwhistle had 20,000 head driven from the northernmost parts of Scotland to Great Close near Malham,[36]:53 a distance of ca 300 miles (483 km).

In modern times dairy farming has predominated. After the 1970s Holstein Friesians became the most popular breed.[37]

Crops

Pollen analysis shows that the peak of arable agriculture in Craven was 320-410 AD. But outbreaks of pestilence in the 6th century and in the 7-8th century resulted in a shift away from ploughing to grazing. However, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the Danish Viking settlers “were engaged in ploughing and making a living for themselves.”[9]:47 Cultivation lynchet terraces and ridge-and-furrow fields of the Middle Ages are visible alongside many villages particularly in Wharfedale and Malhamdale[9]:69 and tithe records show they grew crops of oats, barley and wheat[36]:21 and in rotation, beans and peas.[9]:71 But the wool boom of the 16th century caused most arable land to be turned into pasture. In the 18th century miller’s records show they had to import wheat to grind and sell as flour[36]:21 but the farmers still grew oats for it formed the principle article of their subsistence, some made into bread and puddings[38] but mostly cooked as oatcakes.

“We were browt up on haverbreead and cheese”

Administration

In the 18th century the national Board of Agriculture commissioned a survey of agriculture in the region with a view of improving it. This was published to the public in 1793 as General view of the Agriculture of the West Riding of Yorkshire[39] a 140-page book detailing every factor. The wide variety of soil composition resulted in tithes ranging from 6 shillings up to 3 pounds per acre and farms leasing from 50 to 500 pounds per year. It details by parish quantities of cattle and crop produced, their rotation and market value. The report recommended more wheat and turnips; more sheep and of better breed; criticized poor drainage and design of farm buildings and taught principles of farm management.

Average wages then paid to employees were 12 pounds per annum with victuals and drink; and to temporary labourers 2 shillings and sixpence per day with beer. Hours of work in winter were “dawn till dark” and in harvest time “six till six, with one hour for dinner and another for drinking”. The author shows concern for their virtue and welfare.

Government

Parliamentary Constituency

Since 1983 Craven has been in the Parliamentary Constituency of Skipton & Ripon. This constituency is considered one of the safest seats in England with a long history of Conservative representation. The Member of Parliament was: John Watson 1983 to 1987; David Curry 1987 to 2010; Julian Smith 2010 to —.

County Council

North Yorkshire County Council administers an area of 8,654 square kilometres (3,341 sq mi), the largest county in England. It is a non-metropolitan county that operates a cabinet-style council in Northallerton. The 72 councillors therein elect a council leader who appoints up to 9 councillors to form the executive cabinet.[40]

District Divisions

Craven, for representation on North Yorkshire County Council, is divided into seven Divisions and each returns one councillor.[41]

- Airedale[42]

- Mid-Craven[43]

- North Craven[44]

- Ribblesdale[45]

- Skipton East[46]

- Skipton West[47]

- South Craven[48]

District Council

Elections to Craven District Council are held in three out of every four years, with one third of the 30 seats on the council being elected at each election. Since the first election to the council in 1973 the council has alternated between periods when no party had overall control and times when the Conservatives had a majority, apart from a 2-year period between 1996 and the 1998 election when the Liberal Democrats had a majority. After no party had a majority since 2001, the Conservatives regained overall control at the 2010 election and have held it since.[49] After the July 2014 Skipton West by-election the council is composed of the following councillors:-

| Party | Councillors | |

| Conservative Party | 18 | |

| Independent | 9 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 2 | |

| Labour Party | 1 | |

District Council wards

There are 76 Civil Parishes in Craven

They are grouped into 19 Wards. The Wards are represented by 30 councillors; eight wards by one councilor and eleven by two councilors. The wards are:

- Aire Valley with Lothersdale Ward : Parishes of Bradleys Both, Cononley, Farnhill, Kildwick, Lothersdale (two councilors)

- Barden Fell Ward : Parishes of Appletreewick, Barden, Beamsley, Bolton Abbey, Bordley, Burnsall, Cracoe, Draughton, Hazlewood-with-Storiths, Halton East, Hetton, Rylstone, Thorpe.

- Bentham Ward : Parishes of Bentham and Burton-in-Lonsdale (two councilors)

- Cowling Ward : Parish of Cowling.

- Embsay with Eastby Ward : Parish of Embsay with Eastby.

- Gargrave and Malhamdale Ward : Parishes of Airton, Bank Newton, Calton, Coniston Cold, Eshton, Flasby-with-Winterburn, Gargrave, Hanlith, Kirkby Malham, Malham, Malham Moor, Otterburn, Scosthrop, Stirton-with-Thorlby (two councilors)

- Glusburn Ward : Parish of Glusburn and Cross Hills (two councilors)

- Grassington Ward : Parishes of Grassington, Hebden, Hartlington, Linton.

- Hellifield and Long Preston Ward : Parishes of Hellifield, Long Preston, Nappa, Swinden.

- Ingleton and Clapham Ward : Parishes of Austwick, Clapham-cum-Newby, Ingleton, Lawkland, Thornton-in-Lonsdale. (two councilors)

- Penyghent Ward : Parishes of Giggleswick, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Stainforth.

- Settle and Ribble Banks Ward : Parishes of Halton West, Langcliffe, Rathmell, Settle, Wigglesworth (two councilors)

- Skipton East Ward : Parish of Skipton (two councilors)

- Skipton North Ward : Parish of Skipton (two councilors)

- Skipton South Ward : Parish of Skipton (two councilors)

- Skipton West Ward : Parish of Skipton (two councilors)

- Sutton-in-Craven Ward : Parish of Sutton-in-Craven (two councilors)

- Upper Wharfedale Ward : Parishes of Arncliffe, Buckden, Conistone-with-Kilnsey, Halton Gill, Hawkswick, Kettlewell-with-Starbotton, Linton, Threshfield.

- West Craven Ward : Parishes of Broughton, Carleton, Elslack, Martons Both, Thornton-in-Craven.[50]

Allied Organizations

Craven District Council allies with other organizations:[51]

- North Yorkshire County is a two tier local authority area, with NYCC being the top and Craven District Council the bottom tier. Whilst CDC is responsible for providing some services NYCC is responsible for others.[52]

- The Leeds City Region is the economic area comprising Craven, Harrogate, York, Bradford, Leeds, Selby, Calderdale, Kirklees, Wakefield and Barnsley. LCR members work together in fields such as transport, housing and spatial planning.[53]

- North Yorkshire Strategic Partnership is a partnership of public sector, private sector and voluntary organizations in Craven working together to meet the needs of the communities.[54]

- North Yorkshire Children's Trust, part of the NYSP, represents all those agencies that working with children and young people across the county. NYCT promotes the five national Every Child Matters outcomes for children.[55]

- York and North Yorkshire Cultural Partnership brings together a number of Yorkshire agencies that bring the benefits of culture to quality of life and economic regeneration. This partnership is working together to deliver the York and North Yorkshire Cultural Strategy 2009–2014.[56]

- Welcome to Yorkshire works to improves what the region has to offer tourists.[57]

Other Cravens

West Craven

In the 1974 government reorganization of the shire districts some towns were lost to Lancashire but because of cultural history some of them, all now part of the borough of Pendle, came to be known as West Craven. These are Barnoldswick, Earby, Sough, Kelbrook, Salterforth and Bracewell and Brogden. (Other more westerly parts of Craven which became parts of Ribble Valley in modern Lancashire such as Gisburn, are not normally referred to as part of West Craven.)

Archdeaconry of Craven

The Anglican Church Archdeaconry number 542 is named Craven and has four Deaneries: Ewecross, Bowland, Skipton and South Craven.[58] Ecclesiastic Craven is much larger than the civic District of Craven; in particular northern Ewecross is in Cumbria county, lower South Craven is in West Yorkshire, and south-west Bowland is in Lancashire county. The Church of England has considered changing their boundary of Bowland to match that of civic Lancashire[59]

Deanery of South Craven

The Deanery of South Craven is much bigger than the council election division of South Craven, for the Deanery of South Craven comprises 20 parishes: Cononley, Cowling, Cross Roads cum Lees, Cullingworth, Denholme, East Morton, Harden, Haworth, Ingrow, Kildwick, Newsholme, Oakworth, Oxenhope, Riddlesden, Sildsden, Steeton with Eastburn, Sutton-in-craven, Thwaites Brow, Utley, Wilsden. The Civic boundaries further contrast in that only Bradley, Cowling, Kildwick and Sutton-in-craven are in North Yorkshire, the other 16 are in West Yorkshire.

Towns

The largest town in Craven is Skipton. Other major population centres in the region include High Bentham, Settle, Grassington. The expanded villages of Sutton-in-Craven, Cross Hills and Glusburn are now considered one urban conglomerate.

Geography

Craven comprises the upper reaches of Airedale, Wharfedale, Ribblesdale and the river Wenning of Lonsdale.

Topography

Craven is a group of valleys. Through Craven the River Aire and River Wharfe flow east to the North Sea; and the River Ribble and River Wenning flow west to the Irish Sea.

To Craven's north stand limestone mountains of up to 736 m (2,415 ft) above mean sea level[60] and to its south lie bleak sandstone moors, that above 275 m (902 ft) grow little but bracken.[61]

Transport can find the Pennines a formidable barrier for roads can be blocked by snow for several days. But Craven makes a sheltered passageway with low passes

Natural vegetation

At the end of the last ice age ca 11,500 years ago plants returned to the bare earth and archaeological palynology can identify their species. The first trees to colonise were willow, birch and juniper, followed later by alder and pine. By 6500 BC temperatures were warmer and woodlands covered 90% of the dales with mostly pine, elm, lime and oak. On the limestone soils the oak was slower to colonize and pine and birch predominated. Around 3000 BC a noticeable decline in tree pollen indicates that Neolithic farmers were clearing woodland to increase grazing for domestic livestock, and studies at Linton Mires and Eshton Tarn find an increase in grassland species in Craven.[9]

On poorly drained impermeable areas of millstone grit, shale or clays the topsoil gets waterlogged in Winter and Spring. Here tree suppression combined with the heavier rainfall results in blanket bog up to 2 m (7 ft) thick. The erosion of peat ca 2010 still exposes stumps of ancient trees.[9]

“In digging it away they frequently find vast fir trees, perfectly sound, and some oaks...”

Vegetation in the Pennines is adapted to subarctic climates, but altitude and acidity are also factors. For example on Sutton Moor the millstone grit’s topsoil below 275 m (902 ft) has a soil ph that is almost neutral, ph 6 to 7, and so grows good grazing. But above 275 m (902 ft) it is acidic, ph 2 to 4, and so can grow only bracken, heather, sphagnum, and coarse grasses[61] such as cottongrass, purple moor grass and heath rush.[31] However dressing it with lime produces better quality grass for sheep grazing. Such is named marginal upland grazing.[61] This suggests that early pastoral farming on millstone grit soil flourished in areas where lime was most easily available.

Demography

- The population is increasing and growing older. By 2020 Craven’s population is projected at 63,400, an increase of 14.2% (2006 based sub-national population projections ONS)[63]

- 95.6% of the Districts population is white British, with ethnic minority (BME) groups making up 4.4% (Mid Year 2006 Population Estimates, Experimental Statistics ONS).

- Young people aged 19 and under make up 22% of the population, those aged 20 to 64 make up 56%, and those aged 65 and over 22% (Mid Year 2008 Population Estimates, ONS)

- 17.23% of the population consider themselves to have a long-term limiting illness or disability (2001 Census Statistics ONS).[51]

Economy

| Sector | Quantity | % |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 213 | 7.2 |

| Construction | 369 | 12.5 |

| Distribution, Hotels and Restaurants | 972 | 32.8 |

| Transport and Communications | 157 | 5.3 |

| Banking, Finance and Insurance | 760 | 25.6 |

| Public Admin, Education and Health | 271 | 9.1 |

| Other | 221 | 7.5 |

Economic forecasts for 2010 show that the Craven District's diverse economy, measured in Gross Value Added (GVA), is worth £1.14 billion ($1.87 billion) Since 1998 the value of the District’s economy has grown by 45%. Craven hosts a variety of small businesses - 72% employ less than four people. Businesses that employ above 50 employees (2.2%) are mostly in the south of the District.

- The visitor economy sector has the largest number of businesses.

- The banking, finance and insurance sector has experienced significant growth since 2003 mainly through the Skipton Building Society group.

- Agriculture and land-based industries form a significant part of the District’s economy, particularly within the remoter areas.

- Manufacturing has declined since 2003 but is still a key sector: Major manufacturers are Johnson & Johnson Wound Management and Angus Fire & Transtechnology.[51][65]

Traditional mainstays

Agriculture

The business of agriculture revolves around the Market towns of Craven:

| Market town | Street market | Farmers | Crops auction | Cattle auction | Other livestock |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bentham | Wed | 1st Sat | - | Wed: primestock[67] | 1st Tues: dairy, sheep, seasonals |

| Ingleton | Fri | inactive | - | - | - |

| Settle | Tues | 2nd Sun | - | - | - |

| Gisburn[68] | - | - | Thur: hay and straw | Thur: prime, dairy, sheep[67] | 1st and 3rd Sat: breeding, store |

| Grassington | inactive | 3rd Sun | inactive | inactive | inactive |

| Skipton | Mon Wed Fri Sat | 1st Sat | Mon: crops and produce | Mon: prime, dairy, sheep[69] | 1st and 3rd Wed: store, pedigree |

AHDB, the national Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board,[70] issues regional reports with constant updates on agricultural output:

- CATTLE: For example at Skipton Auction Mart[71] on one day 108 cattle were sold including 55 prime steers, 53 heifers, 2 young bulls and 21 older heifers (July 2011).[72] In June 2013 the top price by weight was 185.5p/kg for two Aberdeen Angus-cross heifers at £1,075 ($1,681) per head.[73]

- SHEEP: For example at Skipton Auction Mart in one day 985 lambs and 278 ewes/rams were sold (July 2011).[72] In June 2013 the top price by weight for lambs was 240.8p/kg at £94 ($147) per head); rams fetched a top price of £79.50 ($124) per head and sheep averaged £47.10 ($73) per head.[73]

- SHEEP DOGS auctions for working dogs are held seasonally at Skipton[74] and Bentham. The world record price was broken in 2011 with £6,300 ($10,270) for Dewi Fan.[75]

- DAIRY: Traditionally Craven milk is mostly sold as cheese. North Yorkshire in 2008 had 649 holdings with 71,518 dairy cows aged over 2 years. Average annual milk yield is 7,406 litres/cow. Wholesale production of milk for all of North Yorkshire 2009/10 was 488,894,588 litres.[76]

Two thirds of Craven lie within the Yorkshire Dales National Park where traditional landscape preservation is required[51][77]

Quarrying

Silurian gritstone is quarried along the North Craven Fault above Ingleton and in Ribblesdale. Lower Carboniferous Great Scar Limestone is quarried in those areas and also near Grassington. Carboniferous reef limestone is quarried around Skipton.[78]

Employment

| Occupation | % |

|---|---|

| Sales and customer service | 6 |

| Personnel services | 7 |

| Process: Plant | 8 |

| Administration | 10 |

| Elementary | 12 |

| Professional occupations | 12 |

| Associate Professionals | 12 |

| Skilled Trades | 16 |

| Managers and senior officials | 17 |

| Sector | Quantity | % |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 362 | 1.4 |

| Manufacturing | 2,602 | 9.8 |

| Construction | 1,759 | 6.6 |

| Distribution, Hotels and Restaurants | 7,383 | 27.8 |

| Transport and Communications | 781 | 2.9 |

| Banking, Finance and Insurance | 7,522 | 28.3 |

| Public Administration, Education and Health | 5,357 | 20.1 |

| Other | 825 | 3.1 |

In 2008 there were 26,591 employed; 22% were self-employed. In 2010 each Full Time Equivalent (FTE) employee contributed £40,311 to the District’s economy, representing an increase in productivity of 21.9% since 1998; an annual increase of 1.8%. The value of output per capita (estimated to be £19,703) has increased by 32% since 1998.[65]

Transport

The district is free from motorways. It was shown a national detailed Land Use Survey by the Office for National Statistics in 2005 that Craven has the least proportion of land taken up by roads of any district in England: 0.7%. This compared with a maximum of over 20% in four London boroughs and the City of London.[80]

Passes

Transport can find the Pennines a formidable barrier for roads can be blocked by snow for several days. Craven is of great significance for the North of England for by its topography provides low-altitude passes through "the backbone of England". They were especially significant for the railway and canal builders. The lowest passes through the Pennines are:

- The Airedale to Ribblesdale pass near Barnoldswick is 144 m (472 ft) at Thornton-in-Craven 53°56′03″N 2°09′46″W / 53.93413°N 2.16276°W

- The Airedale to Ribblesdale pass near Settle is 160 m (525 ft) just East of Hellifield 54°00′00″N 2°10′00″W / 54.00000°N 2.16667°W a point labelled Aire Gap on some maps.[81]

- The Airedale to Pendle Water pass near Colne is 165 m (541 ft) at Foulridge 53°52′36″N 2°10′35″W / 53.8768°N 2.176420°W also sometimes called Aire Gap

- The Ribblesdale to Londsdale pass near Settle is 166 m (545 ft) at Giggleswick Scar 54°04′27″N 2°19′05″W / 54.074167°N 2.318056°W[60]

The nearest alternative pass through the Pennines is Stainmore Gap (Eden-Tees)[82] to the North, but that is not in Craven’s league for it climbs to 420 m (1,378 ft) and its climate is classed as sub-arctic in places.[83]

The nearest low-level routes across the country are over 62 miles (100 km) away: the 228 m (748 ft) Tyne Gap to the north, or the A619 road in Derbyshire to the south.[60]

Main Routes

- A59 road: York, Harrogate, Skipton, Barnoldswick, Clitheroe, Preston, Liverpool

- A65 road: Ilkley, Skipton, Settle, Ingleton, Kendal

- A629 road: Skipton, Keighley, Halifax, Huddersfield, Rotherham

- A56 road: Earby, Colne, M65 motorway, Burnley, Manchester, Chester

- Train: Skipton railway station to Leeds on the Airedale Line

- Train: Skipton railway station to Morecambe on the "Little" North Western Railway

- Train: Settle railway station to Carlisle or Leeds on Settle-Carlisle Railway

A59 York–Liverpool

The A59 road runs along the southern edge of Airedale to Ribblesdale. It runs about 0.62 miles (1 km) north of a disused Roman road through Craven that took the lowest pass through Thornton-in-Craven.

A56 Skipton–Chester

The route now known as the A56—-M65 first developed c.1773–1816 as the Leeds and Liverpool Canal to carry heavy industrial goods like masonry stone, limestone, and coal.[84] The planned route into Ribblesdale was via a lower level pass but the industrial revolution in Nelson and Colne made it seem more profitable to change their route to Foulridge near Colne despite it being the highest pass.

A629 and A65 Keighley–Kendal

The route of the A65 road is perhaps the oldest for it follows a Neolithic trade route for stone axes from central Cumbria. By the 18th century the principal exports were cattle and most imports came on ninety pack horses from Kendal.[85] The cost of that for heavy goods was prohibitive[86] so the textile industrialist of Settle campaigned that the road from Keighley to Kendal be made passable to wheeled vehicles[85] and in 1753 the Keighley and Kendal Turnpike Trust was founded. By 1840 passenger stagecoaches ran daily[86] but in 1878 Parliament abolished all Turnpikes and set up County Councils; and the management of the main roads was transferred to them.[86]:p.7

By 1968 traffic had so increased in volume that it necessitated the rebuilding of the A629 and A65. The Skipton northern bypass of 1981 cost £16.4 million. The Kildwick bypass was completed in 1988.[87]

Education

Educational attainment

The proportion of the working age population with high levels educational attainment is above the national average, and 40% of the District’s residents have managerial and professional occupations. Also Lantra's Landskills offers workshops in efficiency and profitability in agriculture, horticulture and forestry with up to 70% funding. Caven is covered in Farm Business Support and Development and Yorkshire Rural Training Network.[88] Yet from 2004 to 2009 there was generally a decline in attainment of about 12% and the number of people in the District with no qualifications increased by 1.8%. Such people have reduced employment options, however Craven College[89] in Skipton is one of the largest Further Education Colleges in North Yorkshire and provides an outreach service to rural areas.[51]

Museums

Craven Museum & Gallery[90] in Skipton is one of three museums in the district. It has obtained funding to deliver various projects:

- The Phoenix Project; delivered in partnership with the three other museums in Craven increased accessibility of collections.

- The Archaeology in the Landscape project, targeting young people, families and the disadvantaged, delivers events, workshops, demonstrations and education programmes to 3,460 young people and over 17,000 adults.

- The Young Archaeologists Club programme delivered museum education to approx 3,000 students 2009–2010.

As part of the projects above Craven Museum & Gallery staff worked with both the Museum of North Craven Life, The Folly in Settle[91] and the Grassington Folk Museum.[51][92]

Arts

Craven District supports arts through music, theatre, dance, literature, visual arts and festivals. Funding from the Arts Council England (Yorkshire) alone totalled £435,811 between 2006 and 2009. Grants from other sources including the Gulbenkian Fund and Esme Fairburn Trust totalling well over an additional £160,000.[51] A new exhibition gallery was opened in 2005 at Craven Museum & Gallery,[93] Skipton, which now hosts a programme of exhibitions each year.

Sport

Craven Council opened the Craven Pool and Fitness Centre in 2003 and extended it in 2007. The Centre reached the semi-finals in the Best Semi Best Sports Project category of The National Lottery Awards. The Craven Active Sports Network develops opportunities for participation in sport and active recreation, sourcing funding for a variety of projects throughout the District, totaling over £14.5 million in 2001–2011. The National Sport Unlimited Scheme, delivering a programme of sporting activity to 1205 young people and teenagers, brought in £45,000 of external funding.[51]

Notable people

In 1665 Lady Anne Clifford, 14th Baroness de Clifford, owned and restored Skipton Castle.

In 1518 William Craven of Appletreewick was born to a modest family in Appletreewick near Skipton. At age 14 was sent to London to apprentice to a Watling Street Tailor. He qualified in 1569 and made such a fine impression that in 1600 he was made Alderman of Bishopgate; in 1601 he was chosen Lord Mayor of London; and in 1603 was knighted by James I. He is sometimes referred to as "Aptrick's Dick Whittington" suggesting that the story of Dick Whittington is based on his life.[94] William made benefactions to Craven, founding the school in Burnsall.[95]

One of William’s sons, John Craven, founded the famous Craven Scholarships at Oxford and Cambridge Universities and in 1647 left many large charitable bequests to Craven towns including Burnsall and Skipton.

In 1660 William's first son William Craven was made the first Earl of Craven by Charles II. However, that title was eponyminous for the estate was Uffington Berkshire so he was in no sense a lord of Craven Yorkshire.

Gallery

-

River Wenning passing The Punch Bowl in Low Bentham

-

View of High Bentham from the Heritage Trail

-

View of Settle from Castlebergh, a 300 feet (91 m) limestone crag

-

View back across the Ribble to Giggleswick Scar

-

Gargrave's milestone on the Keighley and Kendal Turnpike, 1753 – 1878

-

The River Aire at Gargrave

-

View of Skipton from Skipton Moor

-

Kildwick Bridge west side built 1305-1313 with ribbed vaulting

References

- ↑ "Resident Population Estimates by Ethnic Group (Percentages); Mid-2005 Population Estimates". National Statistics Online. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ↑ Cox, Thomas (1731). "Magna Britannia et Hibernia Antiqua Nova'". Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ↑ "Institute for Name Studies". English Place-Name Society. Retrieved 25 August 2010. Note: Select the Thorton in Craven entry.

- ↑ Genuki Yorkshire Maps

- ↑ Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names, Oxford (1960)

- ↑ Wood, P N (1996). "On the little British kingdom of Craven". Northern History 32.

- ↑ Mills, David (2011). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019960908X.

- ↑ Skaife, Robert; Ellis, A.S. (2012) [1896]. Domesday Book for Yorkshire (new ed.). Ulan Press. ASIN B00AUI62HW.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 White, Robert (2005) [1997]. The Yorkshire Dales, A landscape Through Time (new ed.). Ilkley, Yorkshire: Great Northern Books. ISBN 1-905080-05-0.

- ↑ Roman Britain.org. Retrieved August 2012

- ↑ Ordnance Survey Map OL2 Yorkshire Dales Southern and Western areas ISBN 978-0-319-24068-7

- ↑ Ordnance Survey Map OL41 Forest of Bowland & Ribblesdale ISBN 978-0-319-24071-7

- ↑ Google Earth

- ↑ The genealogical region of Craven, see map on p.2

- ↑ Domesday Book, National Archives

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Labs of the national archives, Domesday on a map

- ↑ The Domesday Book Online, Lancashire Retrieved November 2010

- ↑ Palliser, D.M. (1922). "An introduction to the Yorkshire Domesday". Yorkshire Domesday (London: Alecto Historical Editions): 4–5.

- ↑ Thorn, F.R. (1922). "Hundreds and Wapentakes". Yorkshire Domesday (London: Alecto Historical Editions): 55–60.

- ↑ Hey, D. (1986). Yorkshire from AD 1000 (London): 4. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Roffe, D.R. (1991). "The Yorkshire Summary: a Domesday satellite". Northern History, A Review of the History of the North of England and the Borders 27: 257.

- ↑ R Hindley, the History of Oxenhope, pub 1996 Retrieved November 2010.

- ↑ Roger of Poitou is associated with 632 places after the Conquest Open Domesday, The first free online copy of Domesday Book Retrieved March 2012

- ↑ Dalton, Paul (1994). Conquest, Anarchy a & Lordship: Yorkshire 1066-1154. UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521524644.

- ↑ Overend, Harry (2003). "Kildwick Parish Church". Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ Speight, Harry (1892). The Craven and north-west Yorkshire highlands. pp. 29–60.

- ↑ ’’Domesday Book: Yorkshire’’ Ian Morris, ed. Morris, Faull, Stinson – Phillimore, 1992

- ↑ Hearth Tax Online, Roehampton University, 2010 Retrieved 24 June 2011

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Trevelyan, O.M., George Macaulay (1953) [1926]. "2, 7". History of England, Volume=One: From the Earliest Times to the Reformation (3 ed.). Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday Anchor Books. pp. 207, 208, 313, 314. ISBN 0-385-09234-2.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Talbot, Rob; Whiteman, Robin (1998). Yorkshire Landscapes. London: Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 0-297-82366-3.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kelsall, Dennis; Kelsall, Jan (2008). The Yorkshire Dales: South and West. Milnthorpe: Cicerone. ISBN 978-1-85284-485-1.:26

- ↑ Limestone Country Project Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority. Retrieved 18 June 2013

- ↑ Farming and Forestry Improvement Scheme Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority. Retrieved 18 June 2013

- ↑ Dales Woodland Restoration Yorkshire Dales Millennium Trust. Retrieved 18 June 2013

- ↑ Trees and Woodlands Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority. Retrieved 18 June 2013

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Hartley, Marie; Ingilby, Joan (1968). Life and Tradition in the Yorkshire Dales. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-498-07668-7. Life and Tradition in the Yorkshire Dales

- ↑ Donkin, Kevin (2006). Circular Walks along the Pennine Way (1 ed.). London: Frances Lincoln Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7112-2665-4.

- ↑ Whitaker, Thomas Dunham (1805). The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, in the county of York. Nichols, Payne etc. ISBN 978-1-241-34269-2.Whitaker’s History of Craven pdf. Skipton Castle Co UK. Retrieved 12 June 2013

- ↑ Rennie; Broun; Shirreff (1793). General view of the Agriculture of the West Riding of Yorkshire. London: W Bulmer & Co.

- ↑ "North Yorkshire County Council Constitution". North Yorkshire County Council. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ↑ "Craven election results". North Yorkshire County Council. June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ Airedale Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ Mid-Craven Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ North Craven Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ Ribblesdale Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ Skipton East Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ Skipton West Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ South Craven Electoral Division map and election results

- ↑ "Craven". BBC News Online. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ "List of the Councillors, Wards and parishes of Craven". Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 51.6 51.7 Craven District Council Adopted Local Plan Craven District Council. Retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ North Yorkshire County Council

- ↑ The Leeds City Region

- ↑ North Yorkshire Strategic Partnership (NYSP)

- ↑ The North Yorkshire Children's Trust

- ↑ York and North Yorkshire Cultural Partnership

- ↑ Welcome to Yorkshire

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 http://www.achurchnearyou.com/ A Church Near You

- ↑ "Church of England report could affect churches across Craven". Craven Herald & Pioneer. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Google Earth Altitudes given by Google Earth maps

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 page 4 and page 5, Marginal Upland Grazing Sutton Moor, Domesday Reloaded, BBC 1986

- ↑ Arthur Young (1771) "A Six Month Tour of the North of England’"

- ↑ "Craven". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Annual Business Inquiry 2008

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Craven District Council Economic Development Unit

- ↑ Daelnet

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Richard Turner & Sons of Bentham and Clitheroe

- ↑ Gisburn is now in Lancashire but is still an auction market for Craven

- ↑ Craven Cattle Marts Ltd of Skipton also have auctions of seasonal livestock on Tues, Wed, Fri and Sat

- ↑ http://www.ahdb.org.uk/ The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board

- ↑ CCM Auctions, Skipton Auction Mart. Retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 EBLEX, the organization for the English beef and Sheep Industry

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Selling prices at Skipton Cattle Market Meat Trade News. Retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ Sheepdog sales reports CCM Auctions, Skipton. Retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ World record price broken again at Skipton working dogs sale. pdf

- ↑ Daryco Org UK Daryco Org UK

- ↑ Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority

- ↑ Wilson, Alfred (1992). Geology of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Grassington: Yorkshire Dales National Park Committee. ISBN 0-905455-34-7.

- ↑ NOMIS local labour force survey, annual population survey 2001

- ↑ Key Statistics: Dwellings; Quick Statistics: Population Density; Physical Environment: Land Use Survey 2005 2011 census

- ↑ Bing Maps Enter "Aire Gap, United Kingdom"

- ↑ Ordnance Survey Explorer Map, OL41, Forest of Bowland and Ribblesdale ISBN 978-0-319-24071-7

- ↑ "Regional mapped climate averages". The Met Office.

- ↑ "The Leeds & Liverpool Canal Society Chronology". Northern Heritage. 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Brayshaw, Thomas; Robinson, Ralph M (1932). The Ancient Parish of Giggleswick. London: Halton and Co.OCR copy by North Craven Historical Research Retrieved 30 September 2012

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Introduction To The Main Roads of Kendale British Historyac.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2012

- ↑ Graham Taylor From Keighley to Skipton – a journey of 1900 years Retrieved 6 January 2012

- ↑ http://www.lantra.co.uk/LandSkills-YH Lantra Landskills Yorkshire and Humber

- ↑ Craven College

- ↑ Craven Museum & Gallery, Skipton Retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ The Museum of North Craven Life in Settle

- ↑ Grassington Folk Museum

- ↑ Craven Museum & Gallery Skipton

- ↑ Peach, Howard (2003). "People: Aptrick's Dick Whittington". Curious tales of Old North Yorkshire. Sigma Leisure. pp. 13–14. ISBN 1-85058-793-0. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ↑ "History of Burnsall School". Retrieved 27 March 2011.

Further reading

- Carr, William (1828). The Dialect of Craven [Horæ momenta Cravenæ]. London: Wm. Crofts. ISBN 978-0-554-43398-1.

- Pontefract, Ella; Hartley, Marie (1938). Wharfedale. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-1-870071-21-5.

- Whitaker, Thomas Dunham (1805). The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, in the county of York. Nichols, Payne etc. ISBN 978-1-241-34269-2.. Viewable online as Whitaker’s History of Craven pdf Skipton Castle Co UK. Retrieved 12 June 2013

External links

- Craven at DMOZ

- Craven District Council

- North Yorkshire County Council

- Craven Museum & Gallery, Skipton

- North Craven Historical Research Group, Settle

- The Craven Herald & Pioneer

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||