Covering system

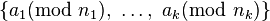

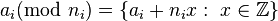

In mathematics, a covering system (also called a complete residue system) is a collection

of finitely many residue classes  whose union contains every integer.

whose union contains every integer.

|

For any arbitrarily large natural number N does there exist an incongruent covering system the minimum of whose moduli is at least N? |

Examples and definitions

The notion of covering system was introduced by Paul Erdős in the early 1930s.

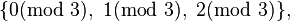

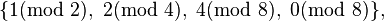

The following are examples of covering systems:

and

and

A covering system is called disjoint (or exact) if no two members overlap.

A covering system is called distinct (or incongruent) if all the moduli  are different (and bigger than 1).

are different (and bigger than 1).

A covering system is called irredundant (or minimal) if all the residue classes are required to cover the integers.

The first two examples are disjoint.

The third example is distinct.

A system (i.e., an unordered multi-set)

of finitely many

residue classes is called an  -cover if it covers every integer at least

-cover if it covers every integer at least

times, and an exact

times, and an exact  -cover if it covers each integer exactly

-cover if it covers each integer exactly  times. It is known that for each

times. It is known that for each

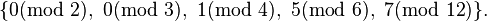

there are exact

there are exact  -covers which cannot be written as a union of two covers. For example,

-covers which cannot be written as a union of two covers. For example,

is an exact 2-cover which is not a union of two covers.

Mirsky–Newman theorem

The Mirsky–Newman theorem, a special case of the Herzog–Schönheim conjecture, states that there is no disjoint distinct covering system. This result was conjectured in 1950 by Paul Erdős and proved soon thereafter by Leon Mirsky and Donald J. Newman. However, Mirsky and Newman never published their proof. The same proof was also found independently by Harold Davenport and Richard Rado.[1]

Primefree sequences

Covering systems can be used to find primefree sequences, sequences of integers satisfying the same recurrence relation as the Fibonacci numbers, such that consecutive numbers in the sequence are relatively prime but all numbers in the sequence are composite numbers. For instance, a sequence of this type found by Herbert Wilf has initial terms

In this sequence, the positions at which the numbers in the sequence are divisible by a prime p form an arithmetic progression; for instance, the even numbers in the sequence are the numbers ai where i is congruent to 1 mod 3. The progressions divisible by different primes form a covering system, showing that every number in the sequence is divisible by at least one prime.

Some unsolved problems

Paul Erdős asked whether for any arbitrarily large N there exists an incongruent covering system the minimum of whose moduli is at least N. It is easy to construct examples where the minimum of the moduli in such a system is 2, or 3 (Erdős gave an example where the moduli are in the set of the divisors of 120; a suitable cover is 0(3), 0(4), 0(5), 1(6), 1(8), 2(10), 11(12), 1(15), 14(20), 5(24), 8(30), 6(40), 58(60), 26(120) ); D. Swift gave an example where the minimum of the moduli is 4 (and the moduli are in the set of the divisors of 2880). S. L. G. Choi proved[2] that it is possible to give an example for N = 20, and Pace P Nielsen demonstrates[3] the existence of an example with N = 40, consisting of more than  congruences.

congruences.

It appears that this problem was solved negatively by Bob Hough, who talked about his work at the Erdős centennial conference in Budapest on July 3 2013.[4] He used the Lovász local lemma to show that there is some maximum N which can be the minimum modulus on a covering system. The proof is in principle effective, though an explicit bound is not given.

In another problem we want that all of the moduli (of an incongruent covering system) be odd. There is a famous unsolved conjecture from Erdős and Selfridge: an incongruent covering system (with the minimum modulus greater than 1) whose moduli are odd, does not exist. It is known that if such a system exists with square-free moduli, the overall modulus must have at least 22 prime factors.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Soifer, Alexander (2008), "Chapter 1. A story of colored polygons and arithmetic progressions", The Mathematical Coloring Book: Mathematics of Coloring and the Colorful Life of its Creators, New York: Springer, pp. 1–9, ISBN 978-0-387-74640-1.

- ↑ S. L. G. Choi (1971). "Covering the set of integers by congruence classes of distinct moduli". Math. Comp. Mathematics of Computation 25 (116): 885–895. doi:10.2307/2004353. JSTOR 2004353.

- ↑ Nielsen, Pace P. (2009). "A covering system whose smallest modulus is 40" (PDF). Journal of Number Theory 129 (3): 640–666. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2008.09.016.

- ↑ Bob Hough (2013). "The least modulus of a covering system". arXiv:1307.0874 [math.NT].

- ↑ Song Guo; Zhi-Wei Sun (14 September 2005). "On odd covering systems with distinct moduli". Adv. Appl. Math. , --187 35 (182). arXiv:math/0412217.

- Guy, Richard K. (2004). Unsolved Problems in Number Theory. Problem Books in Mathematics (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. pp. 383–385. ISBN 0-387-20860-7. Zbl 1058.11001.

External links

- Zhi-Wei Sun: Problems and Results on Covering Systems (a survey) (PDF)

- Zhi-Wei Sun: Classified Publications on Covering Systems (PDF)