Cousin problems

In mathematics, the Cousin problems are two questions in several complex variables, concerning the existence of meromorphic functions that are specified in terms of local data. They were introduced in special cases by P. Cousin in 1895. They are now posed, and solved, for any complex manifold M, in terms of conditions on M.

For both problems, an open cover of M by sets Ui is given, along with a meromorphic function fi on each Ui.

First Cousin problem

The first Cousin problem or additive Cousin problem assumes that each difference

- fi − fj

is a holomorphic function, where it is defined. It asks for a meromorphic function f on M such that

- f − fi

is holomorphic on Ui; in other words, that f shares the singular behaviour of the given local function. The given condition on the fi − fj is evidently necessary for this; so the problem amounts to asking if it is sufficient. The case of one variable is the Mittag-Leffler theorem on prescribing poles, when M is an open subset of the complex plane. Riemann surface theory shows that some restriction on M will be required. The problem can always be solved on a Stein manifold.

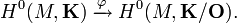

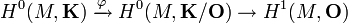

The first Cousin problem may be understood in terms of sheaf cohomology as follows. Let K be the sheaf of meromorphic functions and O the sheaf of holomorphic functions on M. A global section ƒ of K passes to a global section φ(ƒ) of the quotient sheaf K/O. The converse question is the first Cousin problem: given a global section of K/O, is there a global section of K from which it arises? The problem is thus to characterize the image of the map

By the long exact cohomology sequence,

is exact, and so the first Cousin problem is always solvable provided that the first cohomology group H1(M,O) vanishes. In particular, by Cartan's theorem B, the Cousin problem is always solvable if M is a Stein manifold.

Second Cousin problem

The second Cousin problem or multiplicative Cousin problem assumes that each ratio

- fi/fj

is a non-vanishing holomorphic function, where it is defined. It asks for a meromorphic function f on M such that

- f/fi

is holomorphic and non-vanishing. The second Cousin problem is a multi-dimensional generalization of the Weierstrass theorem on the existence of a holomorphic function of one variable with prescribed zeros.

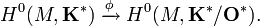

The attack on this problem by means of taking logarithms, to reduce it to the additive problem, meets an obstruction in the form of the first Chern class(See also exponential sheaf sequence). In terms of sheaf theory, let O∗ be the sheaf of holomorphic functions that vanish nowhere, and K∗ the sheaf of meromorphic functions that are not identically zero. These are both then sheaves of abelian groups, and the quotient sheaf K∗/O∗ is well-defined. The multiplicative Cousin problem then seeks to identify the image of quotient map φ

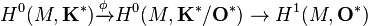

The long exact sheaf cohomology sequence associated to the quotient is

so the second Cousin problem is solvable in all cases provided that H1(M,O∗) = 0. The quotient sheaf K∗/O∗ is the sheaf of germs of Cartier divisors on M. The question of whether every global section is generated by a meromorphic function is thus equivalent to determining whether every line bundle on M is trivial.

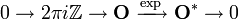

The cohomology group H1(M,O∗), for the multiplicative structure on O∗, can be compared with the cohomology group H1(M,O) with its additive structure by taking a logarithm. That is, there is an exact sequence of sheaves

where the leftmost sheaf is the locally constant sheaf with fiber  . The obstruction to defining a logarithm at the level of H1 is in

. The obstruction to defining a logarithm at the level of H1 is in  , from the long exact cohomology sequence

, from the long exact cohomology sequence

When M is a Stein manifold, the middle arrow is an isomorphism because Hq(M,O) = 0, for  so that a necessary and sufficient condition in that case for the second Cousin problem to be always solvable is that

so that a necessary and sufficient condition in that case for the second Cousin problem to be always solvable is that  .

.

See also

References

- Chirka, E.M. (2001), "Cousin problems", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- Cousin, P. (1895), "Sur les fonctions de n variables", Acta Math. 19: 1–62, doi:10.1007/BF02402869.

- Gunning, Robert C.; Rossi, Hugo (1965), Analytic Functions of Several Complex Variables, Prentice Hall.