Council of Pisa

The Council of Pisa was an unrecognized ecumenical council of the Catholic Church held in 1409 that attempted to end the Western Schism by deposing Benedict XIII (Avignon) and Gregory XII (Rome). Instead of ending the Western Schism, the Council elected a third papal claimant, Alexander V, who would be succeeded by John XXIII.

Preliminaries

The cardinals of the reigning pontiffs being greatly dissatisfied, both with the pusillanimity and nepotism of Gregory XII and the obstinacy and bad will of Benedict XIII, resolved to make use of a more efficacious means, namely a general council. The French king, Charles V, had recommended this, at the beginning of the schism, to the cardinals assembled at Anagni and Fondi in revolt against Urban VI, and on his deathbed he had expressed the same wish (1380). It had been upheld by several councils, by the cities of Ghent and Florence, by the University of Oxford and University of Paris, and by the most renowned doctors of the time, for example: Henry of Langenstein ("Epistola pacis", 1379, "Epistola concilii pacis", 1381); Conrad of Gelnhausen ("Epistola Concordiæ", 1380); Jean de Charlier de Gerson (Sermo coram Anglicis); and especially the latter's master, Pierre d'Ailly, the eminent Bishop of Cambrai, who wrote of himself: "A principio schismatis materiam concilii generalis primus … instanter prosequi non timui" (Apologia Concilii Pisani, in Paul Tschackert). Encouraged by such men, by the known dispositions of King Charles VI and of the University of Paris, four members of the Sacred College of Avignon went to Leghorn where they arranged an interview with those of Rome, and where they were soon joined by others. The two bodies thus united were resolved to seek the union of the Church in spite of everything, and thenceforth to adhere to neither of the competitors. On 2 and 5 July 1408, they addressed to the princes and prelates an encyclical letter summoning them to a general council at Pisa on 25 March 1409. To oppose this project Benedict convoked a council at Perpignan while Gregory assembled another at Aquilea, but those assemblies met with little success, hence to the Council of Pisa were directed all the attention, unrest, and hopes of the Catholic world. The Universities of Paris, Oxford, and Cologne, many prelates, and the most distinguished doctors, like d'Ailly and Gerson, openly approved the action of the revolted cardinals. The princes on the other hand were divided, but most of them no longer relied on the good will of the rival popes and were determined to act without them, despite them, and, if needs were, against them.

Meeting of the Council

On the Feast of the Annunciation, four patriarchs, 22 cardinals and 80 bishops assembled in the Cathedral of Pisa under the presidency of Cardinal de Malesset, Bishop of Palestrina. Among the clergy were the representatives of 100 absent bishops, 87 abbots with the proxies of those who could not come to Pisa, 41 priors and generals of religious orders, and 300 doctors of theology or canon law. The ambassadors of all the Christian kingdoms completed the assembly. Judicial procedure began at once. Two cardinal deacons, two bishops, and two notaries approached the church doors, opened them, and in a loud voice, in the Latin tongue, called upon the rival pontiffs to appear. No one replied. "Has anyone been appointed to represent them?" they added. Again there was silence. The delegates returned to their places and requested that Gregory and Benedict be declared guilty of contumacy. On three consecutive days this ceremony was repeated, and throughout the month of May testimonies were heard against the claimants, but the formal declaration of contumacy did not take place until the fourth session. In defence of Gregory, a German embassy unfavourable to the project of the assembled cardinals went to Pisa (15 April) at the instance of Rupert, King of the Romans. John, Archbishop of Riga, brought several objections before the council, but in general the German delegates aroused hostility and were compelled to flee the city. Carlo Malatesta, Prince of Rimini, adopted a different approach, defending Gregory's cause as a man of letters, an orator, a politician, and a knight, but was still unsuccessful. Benedict refused to attend the council in person, but his delegates arrived very late (14 June), and their claims aroused the protests and laughter of the assembly. The people of Pisa threatened and insulted them. The Chancellor of Aragon was listened to with little favour, while the Archbishop of Tarragona made a rash declaration of war. Intimidated, the ambassadors, among them Boniface Ferrer, Prior of the Grande Chartreuse, secretly left the city and returned to their master.

Contrary to common belief, the French element did not prevail either in numbers or influence. There was a unanimity among the 500 members during the month of June, especially noticeable at the fifteenth general session (5 June 1409). When the usual formality was completed with the request for a definite condemnation of Peter de Luna and Angelo Corrario, the Fathers of Pisa returned a sentence until then unexampled in the history of the Church. All were stirred when the Patriarch of Alexandria, Simon de Cramaud, addressed the august meeting: "Benedict XIII and Gregory XII", said he, "are recognised as schismatics, the approvers and makers of schism, notorious heretics, guilty of perjury and violation of solemn promises, and openly scandalising the universal Church. In consequence, they are declared unworthy of the Supreme Pontificate, and are ipso facto deposed from their functions and dignities, and even driven out of the Church. It is forbidden to them henceforward to consider themselves to be Supreme Pontiffs, and all proceedings and promotions made by them are annulled. The Holy See is declared vacant and the faithful are set free from their promise of obedience." This grave sentence was greeted with joyful applause, the Te Deum was sung, and a solemn procession was ordered next day, the Feast of Corpus Christi. All the members appended their signatures to the decree, and the schism seemed to be at an end. On 15 June the cardinals met in the archiepiscopal palace of Pisa to elect a new pope. The conclave lasted eleven days. Few obstacles intervened from outside to cause delay. Within the council, it is said, there were intrigues for the election of a French pope, but, through the influence of the energetic and ingenious Cardinal Cossa, on 26 June 1409, the votes were unanimously cast in the favour of Cardinal Peter Philarghi, who took the name of Pope Alexander V. The new pope announced his election to all the sovereigns of Christendom, receiving expressions of sympathy for himself and for the position of the Church. He presided over the last four sessions of the council, confirmed all the ordinances made by the cardinals after their refusal of obedience to the antipopes, united the two sacred colleges, and subsequently declared that he would work energetically for reform.

List of cardinals participating in the Council of Pisa and in the election of Alexander V

24 cardinals participated in the election of Antipope Alexander V, including 14 cardinals of the obedience of Rome and 10 of the obedience of Avignon.

Cardinals of the Roman obedience

- Enrico Minutoli (created on December 18, 1389) – Cardinal-Bishop of Frascati; Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals; archpriest of the Liberian Basilica; Camerlengo of the Sacred College of Cardinals

- Antonio Caetani (February 27, 1402) – Cardinal-Bishop of Palestrina; Grand penitentiary; archpriest of the Lateran Basilica

- Angelo d'Anna de Sommariva (December 17, 1384) – Cardinal-priest of S. Pudenziana; Protopriest of the Sacred College of Cardinals

- Corrado Caraccioli (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Priest of S. Crisogono; administrator of the see of Mileto

- Francesco Uguccione (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Priest of SS. Quattro Coronati; administrator of the see of Bordeaux

- Giordano Orsini (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Priest of SS. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti

- Giovanni Migliorati (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Priest of S. Croce in Gerusalemme; administrator of the see of Ravenna

- Pietro Filargo (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Priest of SS. XII Apostoli; administrator of the see of Milan

- Antonio Calvi (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Priest of S. Prassede; archpriest of the Vatican Basilica

- Landolfo Maramaldo (December 21, 1381) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Nicola in Carcere Tulliano; Protodeacon of the Sacred College of Cardinals; legate in Perugia

- Rinaldo Brancaccio (December 17, 1384) – Cardinal-Deacon of SS. Vito e Modesto; commendatario of S. Maria in Trastevere

- Baldassare Cossa (February 27, 1402) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Eustachio; legate in Bologna and Romagna

- Oddone Colonna (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Giorgio in Velabro; bishop of Urbino

- Pietro Stefaneschi (June 12, 1405) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria

Cardinals of the obedience of Avignon

- Gui de Malsec (created on December 20, 1375) – Cardinal-Bishop of Palestrina; Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals

- Niccolò Brancaccio (December 18, 1378) – Cardinal-Bishop of Albano

- Jean de Brogny (July 12, 1385) – Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia e Velletri; Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Church

- Pierre Girard (October 17, 1390) – Cardinal-Bishop of Frascati; Grand penitentiary

- Pierre de Thury (July 12, 1385) – Cardinal-Priest of S. Susanna; Protopriest of the Sacred College of Cardinals

- Pedro Fernández de Frías (January 23, 1394) – Cardinal-Priest of S. Prassede

- Amedeo Saluzzo (December 23, 1383) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Maria Nuova; Protodeacon and Camerlengo of the Sacred College of Cardinals

- Pierre Blain (December 24, 1395) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Angelo in Pescheria

- Louis of Bar (December 21, 1397) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Agata; administrator of the see of Langres

- Antonio de Challant (May 9, 1404) – Cardinal-Deacon of S. Maria in Via Lata; administrator of the see of Tarentaise

Judgment of the Council of Pisa

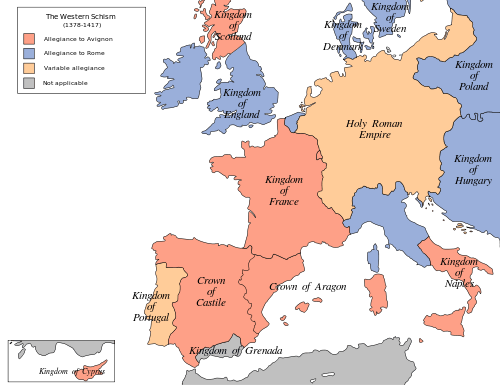

The cardinals considered it their indisputable right to convene a general council to put an end to the schism. The principle behind this was "Salus populi suprema lex esto", i.e. that the safety of and unity of the Church superseded any legal considerations. The behaviour of the two pretenders seemed to justify the council. It was felt that the schism would not end while these two obstinate men were at the head of the opposing parties. There was no undisputed pope who could summon a general council, therefore the Holy See must be considered vacant. There was a mandate to elect an undisputed pope. Famous universities upheld the cardinals' conclusion. However, it was also argued that, if Gregory and Benedict were doubtful, so were the cardinals whom they had created. If the source of their authority was uncertain, so was their competence to convoke the universal Church and to elect a pope. How then could Alexander V, elected by them, have indisputable rights to the recognition of the whole of Christendom? It was also feared that some would make use of this temporary expedient to proclaim the general superiority of the sacred college and of the council to the pope, and to legalize appeals to a future council, which had already commenced under King Philip IV of France. The position of the Church became even more precarious; instead of two heads there were three wandering popes, persecuted and exiled from their capitals. Yet, because Alexander was not elected in opposition to a generally recognized pontiff, nor by schismatic methods, his position was better than that of Clement VII and Benedict XIII, the popes of Avignon. In fact the Pisan pope was acknowledged by the majority of the Church, i.e. by France, England, Portugal, Bohemia, Prussia, a few countries of Germany, Italy, and the County of Venaissin, while Naples, Poland, Bavaria, and part of Germany continued to obey Gregory, and Spain and Scotland remained subject to Benedict.

The Council of Pisa was widely condemned. A violent partisan of Benedict's, Boniface Ferrer, called it "a conventicle of demons". Theodore Urie, a supporter of Gregory, doubted the motives for the gathering at Pisa. St. Antoninus, Thomas Cajetan, Juan de Torquemada, and Odericus Raynaldus all cast doubt on its authority. On the other hand, the Gallican school either approves of it or pleads extenuating circumstances. Noël Alexandre asserts that the council destroyed the schism as far as it could. Bossuet says: "If the schism that devastated the Church of God was not exterminated at Pisa, at any rate it received there a mortal blow and the Council of Constance consummated it." Protestants applaud the council unreservedly, seeing in it "the first step to the deliverance of the world", and greet it as the dawn of the Reformation (Gregorovius). Robert Bellarmine said that the assembly was a general council which was neither approved nor disapproved. It is the original source of all the ecclesiastico-historical events that took place from 1409 to 1414, and opened the way for the Council of Constance.

References

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Council of Pisa". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Council of Pisa". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||