Couette flow

In fluid dynamics, Couette flow is the laminar flow of a viscous fluid in the space between two parallel plates, one of which is moving relative to the other. The flow is driven by virtue of viscous drag force acting on the fluid and the applied pressure gradient parallel to the plates. This type of flow is named in honor of Maurice Marie Alfred Couette, a Professor of Physics at the French university of Angers in the late 19th century.

Simple conceptual configuration

Mathematical description

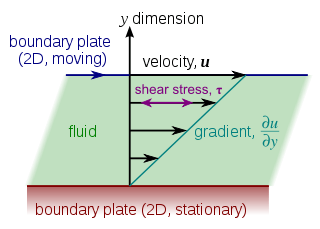

Couette flow is frequently used in undergraduate physics and engineering courses to illustrate shear-driven fluid motion.[1] The simplest conceptual configuration finds two infinite, parallel plates separated by a distance h. One plate, say the top one, translates with a constant velocity u0 in its own plane. Neglecting pressure gradients, the Navier–Stokes equations simplify to

where y is a spatial coordinate normal to the plates and u(y) is the velocity distribution. This equation reflects the assumption that the flow is uni-directional. That is, only one of the three velocity components  is non-trivial. If y originates at the lower plate, the boundary conditions are u(0) = 0 and u(h) = u0. The exact solution

is non-trivial. If y originates at the lower plate, the boundary conditions are u(0) = 0 and u(h) = u0. The exact solution

can be found by integrating twice and solving for the constants using the boundary conditions.

Constant shear

A notable aspect of this model is that shear stress is constant throughout the flow domain.[2] In particular, the first derivative of the velocity, u0/h, is constant. (This is implied by the straight-line profile in the figure.) According to Newton's Law of Viscosity (Newtonian fluid), the shear stress is the product of this expression and the (constant) fluid viscosity.

Couette flow with pressure gradient

A more general Couette flow situation arises when a pressure gradient is imposed in a direction parallel to the plates. The Navier–Stokes equations, in this case, simplify to

where  is the pressure gradient parallel to the plates and

is the pressure gradient parallel to the plates and  is fluid viscosity. Integrating the above equation twice and applying the boundary conditions (same as in the case of Couette flow without pressure gradient) to yield the following exact solution

is fluid viscosity. Integrating the above equation twice and applying the boundary conditions (same as in the case of Couette flow without pressure gradient) to yield the following exact solution

The shape of the above velocity profile depends on the dimensionless parameter

The pressure gradient can be positive (adverse pressure gradient) or negative (favorable pressure gradient).

It may be noted that in the limiting case of stationary plates, the flow is referred to as plane Poiseuille flow with a symmetric (with reference to the horizontal mid-plane) parabolic velocity profile.

Taylor's idealized model

The configuration shown in the figure cannot actually be realized, as two plates cannot extend infinitely in the flow direction. Sir Geoffrey Taylor was interested in shear-driven flows created by rotating co-axial cylinders. In his 1923 paper, Taylor reported the mathematical result (originally derived by Stokes in 1845[3]) that accounts for curvature in the flow direction and has the form[4]

where C1 and C2 are constants that depend on the rotation rates of the cylinders. (Note that r has replaced y in this result to reflect cylindrical rather than rectangular coordinates.) It is clear from this equation that curvature effects no longer allow for constant shear in the flow domain, as shown above. This model is incomplete in that it does not account for near-wall effects in finite-width cylinders, although it is a reasonable approximation if the width is large compared to the space between the cylinders. Generalizations of Taylor's basic model have also been examined. For example, the solution for the time-dependent "start-up" process can be expressed in terms of Bessel functions.[5]

Finite-width model

Taylor's solution accounts for the curvature inherent in the cylindrical devices typically used to create Couette flows, but not the finite nature of the width. A complementary idealization accounts for finiteness, but not curvature. In the figure above, we might think of the "boundary plate" and the "moving plate" as the edges of two cylinders having large radii, say  and

and  , respectively, where

, respectively, where  is only slightly greater than

is only slightly greater than  . In this case, curvature can be neglected locally. The physicist/mathematician Ratip Berker reported a mathematical solution for this configuration in terms of a trigonometric expansion[6]

. In this case, curvature can be neglected locally. The physicist/mathematician Ratip Berker reported a mathematical solution for this configuration in terms of a trigonometric expansion[6]

Wendl's result for physical devices

Actual co-axial cylinder devices used to create Couette flows have both curvature and finite geometry. The latter gives rise to increased drag in the wall region. A mathematical result that accounts for both of these aspects was given only recently by Michael Wendl.[7] His solution takes the form of an expansion of modified (hyperbolic) Bessel functions of the first kind.

See also

References

- ↑ B.R. Munson, D.F. Young, and T.H. Okiishi (2002) Fundamentals of Fluid Mechanics, John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-44250-X.

- ↑ Kundu P and Cohen I. Fluid Mechanics.

- ↑ G.G. Stokes(1845) ``On the theories of the internal friction of fluids in motion and of the equilibrium and motion of elastic solids, in Mathematical and Physical Papers, pp. 102-104, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1880.

- ↑ G.I. Taylor (1923) Stability of a Viscous Liquid Contained between Two Rotating Cylinders, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A 223, 289–343.

- ↑ C.J. Tranter (1968) Bessel Functions with Some Physical Applications, The English Universities Press. (see pp. 115–116).

- ↑ R. Berker (1963) Intégration des équations du mouvement d'un fluide visqueux incompressible, in Handbuch der Physik 8(2), S Flügge (ed.), Springer-Verlag.

- ↑ M.C. Wendl (1999) General Solution for the Couette Flow Profile, Physical Review E 60, 6192–6194.

- Richard Feynman (1964) The Feynman Lectures on Physics: Mainly Electromagnetism and Matter, § 41–6 "Couette flow", Addison–Wesley ISBN 0-201-02117-X .