Corallite

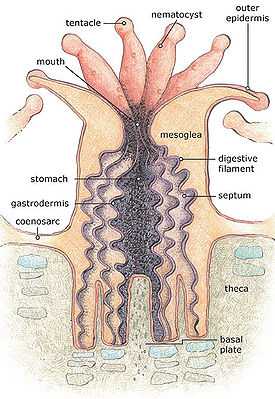

A corallite is the skeletal cup, formed by an individual stony coral polyp, in which the polyp sits and into which it can retract. The cup is composed of aragonite, a crystalline form of calcium carbonate, and is secreted by the polyp. Corallites vary in size, but in most colonial corals they are less than 3 mm (0.12 in) in diameter.[1] The vertical blades inside the corallite are known as septa and in some species, these ridges continue outside the corallite wall as costae.[2] Where there is no corallite wall, the blades are known as septocostae. The septa, costae and septocostae may have ornamentation in the form of teeth and may be thick, thin or variable in size. Sometimes there are paliform lobes, in the form of rods or blades, rising from the inner margins of the septa. These may form a neat circle called the paliform crown. The septa do not usually unite in the centre of the corallite, instead they form a columella, a tangled mass of intertwined septa, or a dome-shaped or pillar-like projection. In the living coral, the lower part of the polyp is in intimate contact with the corallite, and has radial mesenteries between the septa which increase the surface area of the body cavity and aid digestion. The septa, palliform lobes and costae can often be seen through the coenosarc, the layer of living tissue that covers the coenosteum or skeleton of the coral.[3][4]

In colonial species, when the corallites each have a surrounding wall, the colony is said to be plocoid. When the walls are tall and tubular, the colony is phaceloid, and when several polyps share a common wall, the colony is cerioid. Sometimes the polyps are in valleys on the surface of solid corals, they are then known as meandroid.[5] Branching corals have two forms of corallites, axial and radial. The axial corallites tend to be shallow and are found near the tips of the branches while the radial corallites are on the sides of the branches. Corallites can be rounded or polygonal and may be inclined (tilted obliquely to one side).[3]

As long as the colony is alive, the polyps and coenosarc deposit further calcium carbonate under the coenosarc, thus deepening the corallites. Each polyp has a fixed adult size and, when it is beginning to get submerged in the corallite, it secretes a new floor (tabula) beneath itself. Over time, a series of floors builds up below the living polyps, resulting in a thickening and lateral expansion of the coral.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

- ↑ Sprung, Julian (1999). Corals: A quick reference guide. Ricordea Publishing. pp. 220–223. ISBN 1-883693-09-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Corallite". Coral Hub. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- ↑ "The polyp skeleton". Corals of the World. Australian Institute of Marine Science. 2013. Retrieved 2015-04-22.

- ↑ "Colony formation". Corals of the World. Australian Institute of Marine Science. 2013. Retrieved 2015-04-22.