Convex optimization

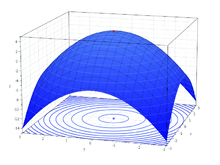

Convex minimization, a subfield of optimization, studies the problem of minimizing convex functions over convex sets. The convexity property can make optimization in some sense "easier" than the general case - for example, any local minimum must be a global minimum.

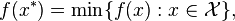

Given a real vector space  together with a convex, real-valued function

together with a convex, real-valued function

defined on a convex subset  of

of  , the problem is to find any point

, the problem is to find any point  in

in  for which the number

for which the number  is smallest, i.e., a point

is smallest, i.e., a point  such that

such that

for all

for all  .

.

The convexity of  makes the powerful tools of convex analysis applicable. In finite-dimensional normed spaces, the Hahn–Banach theorem and the existence of subgradients lead to a particularly satisfying theory of necessary and sufficient conditions for optimality, a duality theory generalizing that for linear programming, and effective computational methods.

makes the powerful tools of convex analysis applicable. In finite-dimensional normed spaces, the Hahn–Banach theorem and the existence of subgradients lead to a particularly satisfying theory of necessary and sufficient conditions for optimality, a duality theory generalizing that for linear programming, and effective computational methods.

Convex minimization has applications in a wide range of disciplines, such as automatic control systems, estimation and signal processing, communications and networks, electronic circuit design, data analysis and modeling, statistics (optimal design), and finance. With recent improvements in computing and in optimization theory, convex minimization is nearly as straightforward as linear programming. Many optimization problems can be reformulated as convex minimization problems. For example, the problem of maximizing a concave function f can be re-formulated equivalently as a problem of minimizing the function -f, which is convex.

Convex optimization problem

An optimization problem (also referred to as a mathematical programming problem or minimization problem) of finding some  such that

such that

where  is the feasible set and

is the feasible set and  is the objective, is called convex if

is the objective, is called convex if  is a closed convex set and

is a closed convex set and  is convex on

is convex on  .

[1]

[2]

.

[1]

[2]

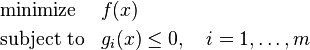

Alternatively, an optimization problem of the form

is called convex if the functions  are convex.[3]

are convex.[3]

Theory

The following statements are true about the convex minimization problem:

- if a local minimum exists, then it is a global minimum.

- the set of all (global) minima is convex.

- for each strictly convex function, if the function has a minimum, then the minimum is unique.

These results are used by the theory of convex minimization along with geometric notions from functional analysis (in Hilbert spaces) such as the Hilbert projection theorem, the separating hyperplane theorem, and Farkas' lemma.

Standard form

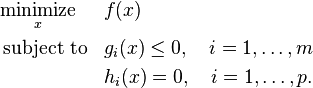

Standard form is the usual and most intuitive form of describing a convex minimization problem. It consists of the following three parts:

- A convex function

to be minimized over the variable

to be minimized over the variable

- Inequality constraints of the form

, where the functions

, where the functions  are convex

are convex - Equality constraints of the form

, where the functions

, where the functions  are affine. In practice, the terms "linear" and "affine" are often used interchangeably. Such constraints can be expressed in the form

are affine. In practice, the terms "linear" and "affine" are often used interchangeably. Such constraints can be expressed in the form  , where

, where  is a column-vector and

is a column-vector and  a real number.

a real number.

A convex minimization problem is thus written as

Note that every equality constraint  can be equivalently replaced by a pair of inequality constraints

can be equivalently replaced by a pair of inequality constraints  and

and  . Therefore, for theoretical purposes, equality constraints are redundant; however, it can be beneficial to treat them specially in practice.

. Therefore, for theoretical purposes, equality constraints are redundant; however, it can be beneficial to treat them specially in practice.

Following from this fact, it is easy to understand why  has to be affine as opposed to merely being convex. If

has to be affine as opposed to merely being convex. If  is convex,

is convex,  is convex, but

is convex, but  is concave. Therefore, the only way for

is concave. Therefore, the only way for  to be convex is for

to be convex is for  to be affine.

to be affine.

Examples

The following problems are all convex minimization problems, or can be transformed into convex minimizations problems via a change of variables:

- Least squares

- Linear programming

- Convex quadratic minimization with linear constraints

- Quadratically constrained Convex-quadratic minimization with convex quadratic constraints

- Conic optimization

- Geometric programming

- Second order cone programming

- Semidefinite programming

- Entropy maximization with appropriate constraints

Lagrange multipliers

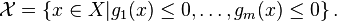

Consider a convex minimization problem given in standard form by a cost function  and inequality constraints

and inequality constraints  , where

, where  . Then the domain

. Then the domain  is:

is:

The Lagrangian function for the problem is

- L(x,λ0,...,λm) = λ0f(x) + λ1g1(x) + ... + λmgm(x).

For each point x in X that minimizes f over X, there exist real numbers λ0, ..., λm, called Lagrange multipliers, that satisfy these conditions simultaneously:

- x minimizes L(y, λ0, λ1, ..., λm) over all y in X,

- λ0 ≥ 0, λ1 ≥ 0, ..., λm ≥ 0, with at least one λk>0,

- λ1g1(x) = 0, ..., λmgm(x) = 0 (complementary slackness).

If there exists a "strictly feasible point", i.e., a point z satisfying

- g1(z) < 0,...,gm(z) < 0,

then the statement above can be upgraded to assert that λ0=1.

Conversely, if some x in X satisfies 1-3 for scalars λ0, ..., λm with λ0 = 1, then x is certain to minimize f over X.

Methods

Convex minimization problems can be solved by the following contemporary methods:[4]

- "Bundle methods" (Wolfe, Lemaréchal, Kiwiel), and

- Subgradient projection methods (Polyak),

- Interior-point methods (Nemirovskii and Nesterov).

Other methods of interest:

- Cutting-plane methods

- Ellipsoid method

- Subgradient method

- Dual subgradients and the drift-plus-penalty method

Subgradient methods can be implemented simply and so are widely used.[5] Dual subgradient methods are subgradient methods applied to a dual problem. The drift-plus-penalty method is similar to the dual subgradient method, but takes a time average of the primal variables.

Convex minimization with good complexity: Self-concordant barriers

The efficiency of iterative methods is poor for the class of convex problems, because this class includes "bad guys" whose minimum cannot be approximated without a large number of function and subgradient evaluations;[6] thus, to have practically appealing efficiency results, it is necessary to make additional restrictions on the class of problems. Two such classes are problems special barrier functions, first self-concordant barrier functions, according to the theory of Nesterov and Nemirovskii, and second self-regular barrier functions according to the theory of Terlaky and coauthors.

Quasiconvex minimization

Problems with convex level sets can be efficiently minimized, in theory. Yuri Nesterov proved that quasi-convex minimization problems could be solved efficiently, and his results were extended by Kiwiel.[7] However, such theoretically "efficient" methods use "divergent-series" stepsize rules, which were first developed for classical subgradient methods. Classical subgradient methods using divergent-series rules are much slower than modern methods of convex minimization, such as subgradient projection methods, bundle methods of descent, and nonsmooth filter methods.

Solving even close-to-convex but non-convex problems can be computationally intractable. Minimizing a unimodal function is intractable, regardless of the smoothness of the function, according to results of Ivanov.[8]

Convex maximization

Conventionally, the definition of the convex optimization problem (we recall) requires that the objective function f to be minimized and the feasible set be convex. In the special case of linear programming (LP), the objective function is both concave and convex, and so LP can also consider the problem of maximizing an objective function without confusion. However, for most convex minimization problems, the objective function is not concave, and therefore a problem and then such problems are formulated in the standard form of convex optimization problems, that is, minimizing the convex objective function.

For nonlinear convex minimization, the associated maximization problem obtained by substituting the supremum operator for the infimum operator is not a problem of convex optimization, as conventionally defined. However, it is studied in the larger field of convex optimization as a problem of convex maximization.[9]

The convex maximization problem is especially important for studying the existence of maxima. Consider the restriction of a convex function to a compact convex set: Then, on that set, the function attains its constrained maximum only on the boundary.[10] Such results, called "maximum principles", are useful in the theory of harmonic functions, potential theory, and partial differential equations.

The problem of minimizing a quadratic multivariate polynomial on a cube is NP-hard.[11] In fact, in the quadratic minimization problem, if the matrix has only one negative eigenvalue, is NP-hard.[12]

Extensions

Advanced treatments consider convex functions that can attain positive infinity, also; the indicator function of convex analysis is zero for every  and positive infinity otherwise.

and positive infinity otherwise.

Extensions of convex functions include biconvex, pseudo-convex, and quasi-convex functions. Partial extensions of the theory of convex analysis and iterative methods for approximately solving non-convex minimization problems occur in the field of generalized convexity ("abstract convex analysis").

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hiriart-Urruty, Jean-Baptiste; Lemaréchal, Claude (1996). Convex analysis and minimization algorithms: Fundamentals. p. 291.

- ↑ Ben-Tal, Aharon; Nemirovskiĭ, Arkadiĭ Semenovich (2001). Lectures on modern convex optimization: analysis, algorithms, and engineering applications. pp. 335–336.

- ↑ Boyd/Vandenberghe, p. 7

- ↑ For methods for convex minimization, see the volumes by Hiriart-Urruty and Lemaréchal (bundle) and the textbooks by Ruszczyński, Bertsekas, and Boyd and Vandenberghe (interior point).

- ↑ Bertsekas

- ↑ Hiriart-Urruty & Lemaréchal (1993, Example XV.1.1.2, p. 277) discuss a "bad guy" constructed by Arkadi Nemirovskii.

- ↑ In theory, quasiconvex programming and convex programming problems can be solved in reasonable amount of time, where the number of iterations grows like a polynomial in the dimension of the problem (and in the reciprocal of the approximation error tolerated):

Kiwiel, Krzysztof C. (2001). "Convergence and efficiency of subgradient methods for quasiconvex minimization". Mathematical Programming (Series A) 90 (1) (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer). pp. 1–25. doi:10.1007/PL00011414. ISSN 0025-5610. MR 1819784. Kiwiel acknowledges that Yuri Nesterov first established that quasiconvex minimization problems can be solved efficiently.

- ↑ Nemirovskii and Judin

- ↑ Convex maximization is mentioned in the subsection on convex optimization in this textbook: Ulrich Faigle, Walter Kern, and George Still. Algorithmic principles of mathematical programming. Springer-Verlag. Texts in Mathematics. Chapter 10.2, Subsection "Convex optimization", pages 205-206.

- ↑ Theorem 32.1 in Rockafellar's Convex Analysis states this maximum principle for extended real-valued functions.

- ↑ Sahni, S. "Computationally related problems," in SIAM Journal on Computing, 3, 262--279, 1974.

- ↑ Quadratic programming with one negative eigenvalue is NP-hard, Panos M. Pardalos and Stephen A. Vavasis in Journal of Global Optimization, Volume 1, Number 1, 1991, pg.15-22.

References

- Bertsekas, Dimitri P.; Nedic, Angelia; Ozdaglar, Asuman (2003). Convex Analysis and Optimization. Belmont, MA.: Athena Scientific. ISBN 1-886529-45-0.

- Bertsekas, Dimitri P. (2009). Convex Optimization Theory. Belmont, MA.: Athena Scientific. ISBN 978-1-886529-31-1.

- Bertsekas, Dimitri P. (2015). Convex Optimization Algorithms. Belmont, MA.: Athena Scientific. ISBN 978-1-886529-28-1.

- Boyd, Stephen P.; Vandenberghe, Lieven (2004). Convex Optimization (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83378-3. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- Borwein, Jonathan, and Lewis, Adrian. (2000). Convex Analysis and Nonlinear Optimization. Springer.

- Hiriart-Urruty, Jean-Baptiste, and Lemaréchal, Claude. (2004). Fundamentals of Convex analysis. Berlin: Springer.

- Hiriart-Urruty, Jean-Baptiste; Lemaréchal, Claude (1993). Convex analysis and minimization algorithms, Volume I: Fundamentals. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences] 305. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. xviii+417. ISBN 3-540-56850-6. MR 1261420.

- Hiriart-Urruty, Jean-Baptiste; Lemaréchal, Claude (1993). Convex analysis and minimization algorithms, Volume II: Advanced theory and bundle methods. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences] 306. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. xviii+346. ISBN 3-540-56852-2. MR 1295240.

- Kiwiel, Krzysztof C. (1985). Methods of Descent for Nondifferentiable Optimization. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-15642-0.

- Lemaréchal, Claude (2001). "Lagrangian relaxation". In Michael Jünger and Denis Naddef. Computational combinatorial optimization: Papers from the Spring School held in Schloß Dagstuhl, May 15–19, 2000. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2241. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 112–156. doi:10.1007/3-540-45586-8_4. ISBN 3-540-42877-1. MR 1900016.

- Nesterov, Y. and Nemirovsky, A. (1994). 'Interior Point Polynomial Methods in Convex Programming. SIAM

- Nesterov, Yurii. (2004). Introductory Lectures on Convex Optimization, Kluwer Academic Publishers

- Rockafellar, R. T. (1970). Convex analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ruszczyński, Andrzej (2006). Nonlinear Optimization. Princeton University Press.

External links

- Stephen Boyd and Lieven Vandenberghe, Convex optimization (book in pdf)

- EE364a: Convex Optimization I and EE364b: Convex Optimization II, Stanford course homepages

- 6.253: Convex Analysis and Optimization, an MIT OCW course homepage

- Brian Borchers, An overview of software for convex optimization

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||