Convention of Chuenpee

| Convention of Chuenpee | |||||||||||

|

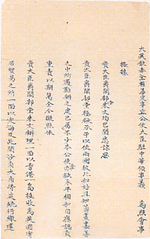

Page one of the convention | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 穿鼻草約 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 穿鼻草约 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Convention of Chuenpee[1] (also spelt Chuenpi or Chuanbi) signed in Guangdong, China, was one of the initial attempts to bring the First Opium War between the Qing dynasty and the United Kingdom to an end. It was drafted in 1841, but not formally ratified due to disagreements between the two parties.[2]

Background

In January 1841, Plenipotentiary Captain Charles Elliot proposed to Qishan, the Governor of Guangdong Province, that a convention be held to end hostilities during the First Opium War. Since the meeting took place close to the Bocca Tigris or Bogue at Shajiao Fort (沙角炮台), also known as Chuanbi fort in Chinese, the convention is commonly known as the Chuanbi Convention. It was held on 20 January in the aftermath of the Second Battle of Chuenpee on 7 January.

Terms

On 20 January, Charles Elliot issued a circular announcing "the conclusion of preliminary arrangements" between Qishan and himself involving the following conditions:[3]

- The cession of the island and harbour of Hong Kong to the British crown. All just charges and duties to the empire upon the commerce carried on there to be paid as if the trade were conducted at Whampoa.

- An indemnity to the British government of six millions of dollars, one million payable at once, and the remainder in equal annual instalments ending in 1846.

- Direct official intercourse between the countries upon equal footing.

- The trade of the port of Canton to be opened within ten days after the Chinese new-year, and to be carried on at Whampoa till further arrangements are practicable at the new settlement.

Other terms that were agreed upon were the restoration of the islands of Chuenpee and Tycocktow to the Chinese, and the evacuation of Chusan, which the British had captured in July 1840.[4] The convention specifically allowed the Qing government to continue collecting tax at Hong Kong, which was the main sticking point that led to the disagreement according to British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston.[2]

Aftermath

News of the agreed terms was sent to England aboard the steamship Enterprise, which left China on 23 January.[5] On the same date, the Canton Free Press published the opinion of British residents in China regarding the cession of Hong Kong:

We consider that, for an independent British settlement, no situation can possibly be more favourably chosen than that of Hong-Kong. The island itself is of little extent ... but it forms, with the neighbouring lands, one of the finest ports existing ... Hong Kong would, we doubt not, in a very short time, become a place of very considerable trade, were its possession by the British not clogged with the condition that the same duties at Whampoa are to be paid there; which, in our estimation, destroys at once all the benefits that might be expected to trade there.[6]

Although Qishan intended to sign the treaty, he had not received formal approval from the Daoguang Emperor and never signed it. When the emperor found out about the treaty, he dismissed Qishan from his position. The British government was also dissatisfied with the treaty and removed Elliot from his position. Many of the terms of the treaty, such as the cession of Hong Kong, were included in the Treaty of Nanking in 1842.

Image gallery

-

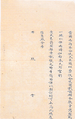

Page two of the convention

-

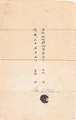

Page three

-

Page four, signed by Charles Elliot

See also

- Sino-British relations

- Possession Point, the area is where Commodore James Bremer, commander-in-chief of the British forces in China, took formal possession of Hong Kong on 26 January 1841

References

Notes

- ↑ Hoe, Susanna; Roebuck, Derek (1999). The Taking of Hong Kong: Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters. Routledge. p. xviii. ISBN 0-7007-1145-7. "Elliot wrote Chuenpee for what some have written Chuenpi and is called Chuanbi in pinyin".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Courtauld, Caroline; Holdsworth, May; Vickers, Simon (1997). The Hong Kong Story. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-590353-6.

- ↑ The Chinese Repository (1841). Volume 10. p. 63.

- ↑ The London Gazette: p. 1423. 3 June 1841. Issue 19984.

- ↑ Eitel, E. J. (1895). Europe in China: The History of Hongkong from the Beginning to the Year 1882. p. 163.

- ↑ Martin, Robert Montgomery (May–August 1841). "Colonial Intelligence". The Colonial Magazine and Commercial-Maritime Journal. Volume 5. p. 108.

Sources

- Lecture notes from Dr. Poon Suk-wah, Lingnan University, Hong Kong.