Convective heat transfer

Convective heat transfer, often referred to simply as convection, is the transfer of heat from one place to another by the movement of fluids. Convection is usually the dominant form of heat transfer in liquids and gases. Although often discussed as a distinct method of heat transfer, convective heat transfer involves the combined processes of conduction (heat diffusion) and advection (heat transfer by bulk fluid flow).

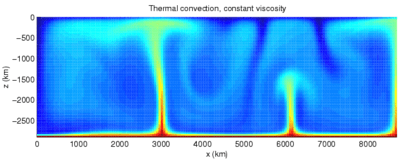

The term convection can sometimes refer to transfer of heat with any fluid movement, but advection is the more precise term for the transfer due only to bulk fluid flow. The process of transfer of heat from a solid to a fluid, or the reverse, is not only transfer of heat by bulk motion of the fluid, but diffusion and conduction of heat through the still boundary layer next to the solid. Thus, this process without a moving fluid requires both diffusion and advection of heat, a process that is usually referred to as convection. Convection that occurs in the earth's mantle causes tectonic plates to move.

Convection can be "forced" by movement of a fluid by means other than buoyancy forces (for example, a water pump in an automobile engine). Thermal expansion of fluids may also force convection. In other cases, natural buoyancy forces alone are entirely responsible for fluid motion when the fluid is heated, and this process is called "natural convection". An example is the draft in a chimney or around any fire. In natural convection, an increase in temperature produces a reduction in density, which in turn causes fluid motion due to pressures and forces when fluids of different densities are affected by gravity (or any g-force). For example, when water is heated on a stove, hot water from the bottom of the pan rises, displacing the colder denser liquid, which falls. After heating has stopped, mixing and conduction from this natural convection eventually result in a nearly homogeneous density, and even temperature. Without the presence of gravity (or conditions that cause a g-force of any type), natural convection does not occur, and only forced-convection modes operate.

The convection heat transfer mode comprises one mechanism. In addition to energy transfer due to specific molecular motion (diffusion), energy is transferred by bulk, or macroscopic, motion of the fluid. This motion is associated with the fact that, at any instant, large numbers of molecules are moving collectively or as aggregates. Such motion, in the presence of a temperature gradient, contributes to heat transfer. Because the molecules in aggregate retain their random motion, the total heat transfer is then due to the superposition of energy transport by random motion of the molecules and by the bulk motion of the fluid. It is customary to use the term convection when referring to this cumulative transport and the term advection when referring to the transport due to bulk fluid motion.[1]

Overview

Convection is the transfer of thermal energy from one place to another by the movement of fluids. Although often discussed as a distinct method of heat transfer, convection describes the combined effects of conduction and fluid flow or mass exchange.

Two types of convective heat transfer may be distinguished:

- Free or natural convection: when fluid motion is caused by buoyancy forces that result from the density variations due to variations of thermal temperature in the fluid. In the absence of an external source, when the fluid is in contact with a hot surface, its molecules separate and scatter, causing the fluid to be less dense. As a consequence, the fluid is displaced while the cooler fluid gets denser and the fluid sinks. Thus, the hotter volume transfers heat towards the cooler volume of that fluid.[2] Familiar examples are the upward flow of air due to a fire or hot object and the circulation of water in a pot that is heated from below.

- Forced convection: when a fluid is forced to flow over the surface by an external source such as fans, by stirring, and pumps, creating an artificially induced convection current.[3]

Internal and external flow can also classify convection. Internal flow occurs when a fluid is enclosed by a solid boundary such when flowing through a pipe. An external flow occurs when a fluid extends indefinitely without encountering a solid surface. Both of these types of convection, either natural or forced, can be internal or external because they are independent of each other. The bulk temperature, or the average fluid temperature, is a convenient reference point for evaluating properties related to convective heat transfer, particularly in applications related to flow in pipes and ducts.

For a visual experience of natural convection, a glass filled with hot water and some red food dye may be placed inside a fish tank with cold, clear water. The convection currents of the red liquid may be seen to rise and fall in different regions, then eventually settle, illustrating the process as heat gradients are dissipated.

Newton's law of cooling

Convection-cooling is sometimes called "Newton's law of cooling"[4] in cases where the heat transfer coefficient is independent or relatively independent of the temperature difference between object and environment. This is sometimes the case, but is not guaranteed to be so. The heat transfer coefficient is often relatively independent of temperature in purely conduction-type cooling, but becomes a function of the temperature in classical natural convective heat transfer. In this case, Newton's law only approximates the result when the temperature changes are relatively small. Another situation with temperature-dependent transfer coefficient is radiative heat transfer.

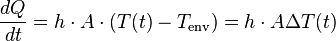

Newton's law, which (as noted) requires a constant heat transfer coefficient, states that the rate of heat loss of a body is proportional to the difference in temperatures between the body and its surroundings. The rate of heat transfer in such circumstances is derived below:[5]

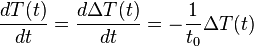

Newton's cooling law is a solution of the differential equation given by Fourier's law:

where

is the thermal energy in joules

is the thermal energy in joules is the heat transfer coefficient (assumed independent of T here) (W/m2 K)

is the heat transfer coefficient (assumed independent of T here) (W/m2 K) is the heat transfer surface area (m2)

is the heat transfer surface area (m2) is the temperature of the object's surface and interior (since these are the same in this approximation)

is the temperature of the object's surface and interior (since these are the same in this approximation) is the temperature of the environment; i.e. the temperature suitably far from the surface

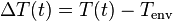

is the temperature of the environment; i.e. the temperature suitably far from the surface is the time-dependent thermal gradient between environment and object

is the time-dependent thermal gradient between environment and object

The heat transfer coefficient h depends upon physical properties of the fluid and the physical situation in which convection occurs. Therefore, a single usable heat transfer coefficient (one that does not vary significantly across the temperature-difference ranges covered during cooling and heating) must be derived or found experimentally for every system that can be analyzed using the presumption that Newton's law will hold.

Formulas and correlations are available in many references to calculate heat transfer coefficients for typical configurations and fluids. For laminar flows, the heat transfer coefficient is rather low compared to turbulent flows; this is due to turbulent flows having a thinner stagnant fluid film layer on the heat transfer surface.[6] However, note that Newton's law breaks down if the flows should transition between laminar or turbulent flow, since this will change the heat transfer coefficient h which is assumed constant in solving the equation.

Newton's law behavior also requires that internal heat conduction within the object be large in comparison to the loss/gain of heat by surface transfer (conduction and/or convection). This allows use of the so-called lumped capacitance model. Again these conditions may not be true (see heat transfer). When internal conduction is rapid as compared with surface heat transfer rates, and Newton's law can be used, the temperature at any time will always be relatively uniform throughout the volume of the object, although of course this single temperature will change exponentially, as time progresses.

Also, an accurate formulation for temperatures may require analysis based on changing heat transfer coefficients at different temperatures, a situation frequently found in free-convection situations, and which precludes accurate use of Newton's law. Assuming these are not problems, then the solution can be given if heat transfer within the object is considered to be far more rapid than heat transfer at the boundary (so that there are small thermal gradients within the object). This condition, in turn, allows the heat in the object to be expressed as conduction.

A correction to Newton's law concerning larger temperature differentials was made in 1817 by Dulong and Petit,[7] who also formulated the Dulong–Petit law concerning the molar specific heat capacity of a crystal.

Solution in terms of object heat capacity

If the entire body is treated as lumped capacitance thermal energy reservoir, with a total thermal energy content which is proportional to simple total heat capacity  , and

, and  , the temperature of the body, or

, the temperature of the body, or  , it is expected that the system will experience exponential decay with time in the temperature of a body.

, it is expected that the system will experience exponential decay with time in the temperature of a body.

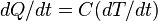

From the definition of heat capacity  comes the relation

comes the relation  . Differentiating this equation with regard to time gives the identity (valid so long as temperatures in the object are uniform at any given time):

. Differentiating this equation with regard to time gives the identity (valid so long as temperatures in the object are uniform at any given time):  . This expression may be used to replace

. This expression may be used to replace  in the first equation which begins this section, above. Then, if

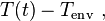

in the first equation which begins this section, above. Then, if  is the temperature of such a body at time

is the temperature of such a body at time  , and

, and  is the temperature of the environment around the body:

is the temperature of the environment around the body:

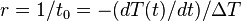

where  is a positive constant characteristic of the system, which must be in units of

is a positive constant characteristic of the system, which must be in units of  , and is therefore sometimes expressed in terms of a characteristic time constant

, and is therefore sometimes expressed in terms of a characteristic time constant  given by:

given by:  . Thus, in thermal systems,

. Thus, in thermal systems,  . (The total heat capacity

. (The total heat capacity  of a system may be further represented by its mass-specific heat capacity

of a system may be further represented by its mass-specific heat capacity  multiplied by its mass

multiplied by its mass  , so that the time constant

, so that the time constant  is also given by

is also given by  ).

).

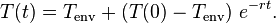

The solution of this differential equation, by standard methods of integration and substitution of boundary conditions, gives:

If:

-

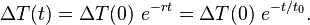

is defined as :

is defined as :  where

where  is the initial temperature difference at time 0,

is the initial temperature difference at time 0,

then the Newtonian solution is written as:

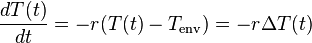

This same solution is more immediately apparent if the initial differential equation is written in terms of  , as a single function of time to be found, or "solved for."

, as a single function of time to be found, or "solved for."

References

- ↑ Incropera DeWitt VBergham Lavine 2007, Introduction to Heat Transfer, 5th ed., pg. 6 ISBN 978-0-471-45727-5

- ↑ http://biocab.org/Heat_Transfer.html Biology Cabinet organization, April 2006, “Heat Transfer”, Accessed 20/04/09

- ↑ http://www.engineersedge.com/heat_transfer/convection.htm Engineers Edge, 2009, “Convection Heat Transfer”,Accessed 20/04/09

- ↑ based on a work by Newton published anonymously as "Scala graduum Caloris. Calorum Descriptiones & signa." in Philosophical Transactions, 1701, 824–829; ed. Joannes Nichols, Isaaci Newtoni Opera quae exstant omnia, vol. 4 (1782), 403–407.

- ↑ Louis C. Burmeister, (1993) “Convective Heat Transfer”, 2nd ed. Publisher Wiley-Interscience, p 107 ISBN 0-471-57709-X, 9780471577096, Google Book Search. Accessed 20-03-09

- ↑ http://www.engineersedge.com/heat_transfer/convection.htm Engineers Edge, 2009, “Convection Heat Transfer”,Accessed 20/03/09

- ↑ Whewell, William (1866). History of the Inductive Sciences from the Earliest to the Present Times.

See also

- Heat transfer coefficient

- Heisler Chart

- Thermal conductivity