Constructed wetland

A constructed wetland (CW) is an artificial wetland created as a new or restored habitat for native and migratory wildlife, for anthropogenic discharge such as wastewater, stormwater runoff, or sewage treatment, for land reclamation after mining, refineries, or other ecological disturbances such as required mitigation for natural areas lost to a development.

Constructed wetlands serve mainly a purpose of treating contaminated water.[1] They are engineered systems that use natural functions of vegetation, soil, and organisms to treat different water streams. Depending on the type of (waste-)water stream that has to be treated the system has to be adjusted accordingly which means that pre- or post-treatments might be necessary.

Natural wetlands act as a biofilter, removing sediments and pollutants such as heavy metals from the water, and constructed wetlands can be designed to emulate these features.

Terminology

Many terms are used to denote constructed wetlands, such as reed beds, soil infiltration beds, constructed treatment wetlands, treatment wetlands, etc. Beside "engineered" wetlands, the terms of "man-made" or "artificial" wetlands are often found as well.[2] A biofilter has some similarities with a constructed wetland, but is usually without plants.

However, the term of constructed wetlands can also be used to describe restored and recultivated land that was destroyed in the past through draining and converting into farmland, or mining.

Overview

.jpg)

.jpg)

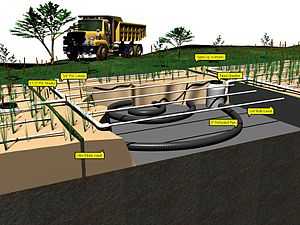

A constructed wetland is an engineered sequence of water bodies designed to filter and treat waterborne pollutants found in sewage, industrial effluent or storm water runoff. Constructed wetlands are used for sewage treatment in particular or wastewater treatment in general. They can be used together with septic tanks[3] as primary treatment, Imhoff tanks or screens in order to separate the solids from the liquid effluent. Some designs however are being used to act as primary treatment as well.[4]

Constructed wetlands can also be used to treat greywater only, and can be incorporated into an ecological sanitation approach.

Vegetation in a wetland provides a substrate (roots, stems, and leaves) upon which microorganisms can grow as they break down organic materials. This community of microorganisms is known as the periphyton. The periphyton and natural chemical processes are responsible for approximately 90 percent of pollutant removal and waste breakdown. The plants remove about seven to ten percent of pollutants, and act as a carbon source for the microbes when they decay. Different species of aquatic plants have different rates of heavy metal uptake, a consideration for plant selection in a constructed wetland used for water treatment. Constructed wetlands are of two basic types: subsurface flow and surface flow wetlands.

Many regulatory agencies list treatment wetlands as one of their recommended "best management practices" for controlling urban runoff.

Types

The main two constructed wetlands types are:

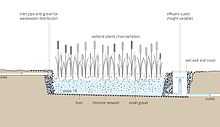

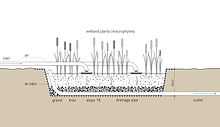

- Subsurface flow constructed wetland - this wetland can be either with vertical flow (the effluent moves vertically, from the planted layer down through the substrate and out) or with horizontal flow (the effluent moves horizontally, parallel to the surface)

- Surface flow constructed wetland

Both types are placed in a basin with a substrate. In most cases, the bottom is lined with either a polymer geomembrane, concrete or clay (when there is appropriate clay type) in order to protect the water table and surrounding grounds. The substrate can be either gravel—generally limestone or pumice/volcanic rock, depending on local availability, sand or a mixture of various sizes of media (for vertical flow constructed wetlands).

Subsurface flow wetland

Subsurface flow wetlands can be further classified as horizontal flow and vertical flow constructed wetlands. In the vertical flow constructed wetland, the effluent moves vertically from the planted layer down through the substrate and out. In the horizontal flow CW the effluent moves horizontally, parallel to the surface. Vertical flow CWs are considered to be more efficient with less area required compared to horizontal flow CWs. However, they need to be interval-loaded and their design requires more know-how while horizontal flow CWs can receive wastewater continuously and are easier to build.[2]

Subsurface flow wetlands move effluent (household wastewater, agricultural, paper mill wastewater [6][7] or, in rarer cases, mining runoff, tannery or meat processing wastes, or storm drains, or other water to be cleansed) through a sand medium on which plants are rooted. A gravel medium (generally limestone or volcanic rock lavastone) can be used as well and is mainly deployed in horizontal flow systems though it does not work as efficiently as sand.[2] Subsurface wetlands are less hospitable to mosquitoes, (as there is no water exposed to the surface) whose populations can be a problem in surface flow constructed wetlands. Subsurface flow systems have the advantage of requiring less land area for water treatment than surface flow. Since subsurface flow systems serve basically to clean water, surface flow wetlands can be more suitable for wildlife habitat.

Constructed subsurface flow wetlands are meant as secondary water treatment systems which means that the effluent needs to pass a primary treatment which effectively removes solids. Such a primary treatment can consist of sand and grit removal, grease trap, compost filter, septic tank, Imhoff tank, Baffled tank, or upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor.[2] The following treatment is based on different biological and physical processes like filtration, adsorption or nitrification. Most important is the biological filtration through a biofilm of aerobic or facultative bacteria. Coarse sand in the filter bed provides a surfaces for microbial growth and supports the adsorption and filtration processes. For those microorganisms the oxygen supply needs to be sufficient. The efficiency of the aerobic treatment depends on the ration between biological oxygen demand (BOD) which is a measure for the organic matter and the oxygen supply which is determined by the design of the CW.[2]

The French System combines primary and secondary treatment of raw wastewater. The effluent passes various filter beds whose grain size is getting smaller (from gravel to sand).[2]

Overloading peaks should not cause performance problems while continuous overloading lead to a loss of treatment capacity through too much suspended solids, sludge or fats. Subsurface flow wetlands need maintenance, such as regular checking of the pretreatment process, of pumps, of influent loads and distribution on the filter bed.[2]

For urban applications the area requirement of a subsurface flow CW might be a limiting factor compared to conventional municipal wastewater treatment plants. However, there are attempts to build them on the roof of buildings. High rate aerobic treatment processes like activated sludge plants, trickling filters, rotating discs, submerged aerated filters or membrane bioreactor plants require less space. The advantage of subsurface flow CWs compared to those technologies is their operational robustness which is particularly important in developing countries and countries in transition. The fact that CWs do not produce secondary sludge is another advantage in cases where adequate secondary sludge disposal is missing.[2]

Plantings of reedbeds are popular in European constructed subsurface flow wetlands. Other plants are cattails (Typha spp.) and sedges.

The costs of subsurface flow CWs mainly depend on the costs of sand with which the bed has to be filled. Another factor is the cost of land.

The quality of the effluent is determined by the design and should be customized for the intended reuse application (like irrigation or toilet flushing) or disposal and comply with the specific regulations for the respective country.

Especially in warm and dry climates the effects of evapotranspiration and precipitation are significant. In cases of water loss, a vertical flow CW is preferable to a horizontal because of an unsaturated upper layer and a shorter retention time.

The effluent can have a yellowish or brownish colour if domestic wastewater or blackwater is treated. Treated greywater usually does not tend to have a colour. Concerning pathogen levels, treated greywater meets the standards of pathogen levels for safe discharge to surface water. Treated domestic wastewater might need a tertiary treatment, depending on the intended reuse application.[2]

Surface flow wetland

Surface flow wetlands, also known as free water surface constructed wetlands, imitate naturally occurring processes in marshes or swamps. As the effluent moves above the soil the particles in the effluent settle, pathogens are destroyed and nutrients are used by plants and organisms. Those types are mainly used as tertiary treatment or even after such one.[5] Blackwater which has a high pathogen load needs to be pretreated in order to not accumulate pathogen solids and garbage.

Pathogens are destroyed by natural decay, predation from higher organisms, sedimentation and UV irradiation since the water is exposed to direct sunlight. The soil layer below the water is anaerobic but the roots of the plants release oxygen around them, this allows complex biological and chemical reactions.

Surface flow wetlands can be supported by a wider variety of soil types including bay mud and other silty clays.

Plants such as Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and Pontederia spp. are used worldwide (although Typha and Phragmites are highly invasive). Recent research in use of constructed wetlands for subarctic regions has shown that buckbeans (Menyanthes trifoliata) and pendant grass (Arctophila fulva) are also useful for metals uptake.

However, surface flow constructed wetlands may encourage mosquito breeding. They may also have high algae production that lowers the effluent quality and due to open water surface mosquitos and odours, it is more difficult to integrate them in an urban neighbourhood.

Hybrid systems

A combination of different types of constructed wetlands is possible to use the specific advantages of each system.[2]

Hybrid systems for example aerate the water after it exits the final reedbed using cascades such as Flowforms before holding the water in a shallow pond.[8] Also, primary treatments as septic tanks, and different types of pumps as grinder pumps may also be added.[9]

Contaminants removal

Overview

Physical, chemical, and biological processes combine in wetlands to remove contaminants from wastewater. An understanding of these processes is fundamental not only to designing wetland systems but to understanding the fate of chemicals once they enter the wetland. Theoretically, wastewater treatment within a constructed wetland occurs as it passes through the wetland medium and the plant rhizosphere. A thin film around each root hair is aerobic due to the leakage of oxygen from the rhizomes, roots, and rootlets.[10] Aerobic and anaerobic micro-organisms facilitate decomposition of organic matter. Microbial nitrification and subsequent denitrification releases nitrogen as gas to the atmosphere. Phosphorus is coprecipitated with iron, aluminium, and calcium compounds located in the root-bed medium.[11][12][13][14][15] Suspended solids filter out as they settle in the water column in surface flow wetlands or are physically filtered out by the medium within subsurface flow wetland cells. Harmful bacteria and viruses are reduced by filtration and adsorption by biofilms on the rock media in subsurface flow and vertical flow systems.

Nitrogen removal

The dominant forms of nitrogen in wetlands that are of importance to wastewater treatment include organic nitrogen, ammonia, ammonium, nitrate, nitrite, and nitrogen gases. Inorganic forms are essential to plant growth in aquatic systems but if scarce can limit or control plant productivity.[16] Total Nitrogen refers to all nitrogen species. Wastewater nitrogen removal is important because of ammonia’s toxicity to fish if discharged into watercourses. Excessive nitrates in drinking water is thought to cause methemoglobinemia in infants, which decreases the blood's oxygen transport ability. The UK has experienced a significant increase in nitrate concentration in groundwater and rivers.[17]

Organic nitrogen

Mitsch & Gosselink define nitrogen mineralisation as "the biological transformation of organically combined nitrogen to ammonium nitrogen during organic matter degradation".[18] This can be both an aerobic and anaerobic process and is often referred to as ammonification. Mineralisation of organically combined nitrogen releases inorganic nitrogen as nitrates, nitrites, ammonia and ammonium, making it available for plants, fungi and bacteria.[18] Mineralisation rates may be affected by oxygen levels in a wetland.[15]

Ammonia removal

The formation of ammonia (NH

3) occurs via the mineralisation or ammonification of organic matter under either anaerobic or aerobic conditions.[19] The ammonium ion (NH+

4) is the primary form of mineralized nitrogen in most flooded wetland soils. This ion forms when ammonia combines with water.[18]

Upon formation, several pathways are available to the ammonium ion. It can be absorbed by plants and algae and converted back into organic matter, or the ammonium ion can be electrostatically held on negatively charged surfaces of soil particles.[18] At this point, the ammonium ion can be prevented from further oxidation because of the anaerobic nature of wetland soils. Under these conditions the ammonium ion is stable and it is in this form that nitrogen predominates in anaerobic sediments typical of wetlands.[15][20]

Most wetland soils have a thin aerobic layer at the surface. As an ammonium ion from the anaerobic sediments diffuses upward into this layer it converts to nitrite or nitrified.[21] An increase in the thickness of this aerobic layer results in an increase in nitrification.[15] This diffusion of the ammonium ion sets up a concentration gradient across the aerobic-anaerobic soil layers resulting in further nitrification reactions.[15][21]

Nitrification is the biological conversion of organic and inorganic nitrogenous compounds from a reduced state to a more oxidized state.[22] Nitrification is strictly an aerobic process in which the end product is nitrate (NO−

3); this process is limited when anaerobic conditions prevail.[15] Nitrification will occur readily down to 0.3 ppm dissolved oxygen.[19] The process of nitrification (1) oxidizes ammonium (from the sediment) to nitrite (NO−

2), and then (2) nitrite is oxidized to nitrate (NO−

3).

Two different bacteria are required to complete this oxidation of ammonium to nitrate. Nitrosomonas sp. oxidizes ammonium to nitrite via reaction (1), and Nitrobacter sp. oxidizes nitrite to nitrate via reaction (2).[19]

Denitrification is the biochemical reduction of oxidized nitrogen anions, nitrate (NO−

3) and nitrite (NO−

2) to produce the gaseous products nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N

2O) and nitrogen gas (N

2), with concomitant oxidation of organic matter.[22] The general sequence is as follows:

NO−

3 → NO−

2 → NO → N

2O → N

2

The end products, N

2O and N

2 are gases that re-enter the atmosphere. Denitrification occurs intensely in anaerobic environments but also in aerobic conditions.[23] Oxygen deficiency causes certain bacteria to use nitrate in place of oxygen as an electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic matter.[15] Denitrification is restricted to a narrow zone in the sediment immediately below the aerobic-anaerobic soil interface.[18][24] Denitrification is considered to be the predominant microbial process that modifies the chemical composition of nitrogen in a wetland system and the major process whereby nitrogen is returned to the atmosphere (N2).[15][25] To summarize, the nitrogen cycle is completed as follows: ammonia in water, at or near neutral pH is converted to ammonium ions; the aerobic bacterium Nitrosomonas sp. oxidizes ammonium to nitrite; Nitrobacter sp. then converts nitrite to nitrate. Under anaerobic conditions, nitrate is reduced to relatively harmless nitrogen gas that enters the atmosphere.

Ammonia removal from domestic sewage

In a review of 19 surface flow wetlands it was found that nearly all reduced total nitrogen.[26] A review of both surface flow and subsurface flow wetlands concluded that effluent nitrate concentration is dependent on maintaining anoxic conditions within the wetland so that denitrification can occur and that subsurface flow wetlands were superior to surface flow wetlands for nitrate removal. The 20 surface flow wetlands reviewed reported effluent nitrate levels below 5 mg/L; the 12 subsurface flow wetlands reviewed reported effluent nitrate ranging from <1 to < 10 mg/L.[27] Results obtained from the Niagara-On-The-Lake vertical flow systems show a significant reduction in both total nitrogen and ammonia (> 97%) when primary treated effluent was applied at a rate of 60L/m²/day. Calculations showed that over 50% of the total nitrogen going into the system was converted to nitrogen gas. Effective removal of nitrate from the sewage lagoon influent was dependent on medium type used within the vertical cell as well as water table level within the cell.[28]

Ammonia removal from mine water

Constructed wetlands have been used to remove ammonia from mine drainage. In Ontario, Canada, drainage from the polishing pond at the Campbell Mine flows by gravity through a 9.3 hectare surface flow constructed wetland during the ice-free season.[29] Ammonia is removed by approximately 95% on inflows of up to 15,000 cubic metres (530,000 cu ft)/day during the summer months, while removal rates decrease to 50-70% removal during cold months. This ammonia was oxidized to nitrate, which was immediately and quantitatively removed in the wetland. Surprisingly, and contrary to Reed (see above), anoxic conditions were not necessary for nitrate removal, which occurred as readily on leaf and detritus biofilm as it did in sediments. Other contaminants, including copper, are also removed in the wetland, such that the final discharge is fully detoxified. Campbell became one of the first gold mines in Ontario to produce a completely non-toxic discharge, as determined by acute and chronic toxicity tests. At the Ranger Uranium Mine, in Australia, ammonia is removed in "enhanced" natural wetlands (rather than fully engineered constructed wetlands), along with manganese, uranium and other metals.

Other mines use natural or constructed wetlands to remove nitrogenous compounds from contaminated mine water, including cyanide (at the Jolu and Star Lake Mines, using natural muskeg and wetlands) and nitrate (demonstrated at the Quinsam Coal Mine). Wetlands were also proposed to remove nitrogenous compounds (present as blasting residues) from diamond mines in Northern Canada. However, land application is equally effective and is easier to implement than a constructed wetland.

Phosphorus removal

Phosphorus occurs naturally in both organic and inorganic forms. The analytical measure of biologically available orthophosphates is referred to as soluble reactive phosphorus (SR-P). Dissolved organic phosphorus and insoluble forms of organic and inorganic phosphorus are generally not biologically available until transformed into soluble inorganic forms.[18]

In freshwater aquatic ecosystems phosphorus is typically the major limiting nutrient. Under undisturbed natural conditions, phosphorus is in short supply. The natural scarcity of phosphorus is demonstrated by the explosive growth of algae in water receiving heavy discharges of phosphorus-rich wastes. Because phosphorus does not have an atmospheric component, unlike nitrogen, the phosphorus cycle can be characterized as closed. The removal and storage of phosphorus from wastewater can only occur within the constructed wetland itself. Phosphorus may be sequestered within a wetland system by:

- The binding of phosphorus in organic matter as a result of incorporation into living biomass,

- Precipitation of insoluble phosphates with ferric iron, calcium, and aluminium found in wetland soils.[18]

Biomass plants incorporation

Higher plants in wetland systems may be viewed as transient nutrient storage compartments absorbing nutrients during the growing season and releasing them at senescence.[30][31] Generally, plants in nutrient-rich habitats accumulate more nutrients than those in nutrient-poor habitats, a phenomenon referred to as luxury uptake of nutrients.[30] Aquatic vegetation may play an important role in phosphorus removal and, if harvested, extend the life of a system by postponing phosphorus saturation of the sediments.[30][32][33] Vascular plants may account for only a small amount of phosphorus uptake with only 5 to 20% of the nutrients detained in a natural wetland being stored in harvestable plant material. Bernard and Solsky also reported relatively low phosphorus retention, estimating that a sedge (Carex sp.) wetland retained 1.9 g of phosphorus per square meter of wetland.[31][34] Bulrushes (Scirpus sp.) in a constructed wetland system receiving secondarily treated domestic wastes contained 40.5% of the total phosphorus influent. The remaining 59.0% was found to be stored in the gravel substratum.[34] Phosphorus removal in a surface flow wetland treatment system planted with one of Scirpus sp., Phragmites sp. or Typha sp. was investigated by Finlayson and Chick (1983).

Phosphorus removal of 60%, 28%, and 46% were found for Scirpus sp., Phragmites sp. and Typha sp. respectively. This may prove to be a low estimate. Vascular plants are a major phosphorus storage compartment accounting for 67.3% of the influent phosphorus.[32] Plant adsorption may reach 80% phosphorus removal.[35]

Only a small proportion (<20%) of phosphate removal by constructed wetlands can be attributed to nutritional uptake by bacteria, fungi and algae.[36] The lack of seasonal fluctuation in phosphorus removal rates suggests that the primary mechanism is bacterial and alga fixation.[37] However, this mechanism may be temporary, because the microbial pool is small and quickly becomes saturated at which point the soil medium takes over as the major contributor to phosphate removal.[38]

Plants create a unique environment at the biofilm's attachment surface. Certain plants transport oxygen which is released at the biofilm/root interface, perhaps adding oxygen to the wetland system.[39] Plants also increase soil or other root-bed medium hydraulic conductivity. As roots and rhizomes grow they are thought to disturb and loosen the medium, increasing its porosity, which may allow more effective fluid movement in the rhizosphere. When roots decay they leave behind ports and channels known as macropores which are effective in channeling water through the soil.[40]

Whether or not wetland systems act as a phosphorus sink or source seems to depend on system characteristics such as sediment and hydrology. There seems to be a net movement of phosphorus into the sediment in many lakes.[41] In Lake Erie as much as 80% of the total phosphorus is removed from the waters by natural processes and is presumably stored in the sediment. Marsh sediments high in organic matter act as sinks.[21] Phosphorus release from a marsh exhibits a cyclical pattern. Much of the spring phosphorus release comes from high phosphorus concentrations locked up in the winter ice covering the marsh; in summer the marsh acts as a phosphorus sponge.[21] Phosphorus is exported from the system following dieback of vascular plants.[42] Phosphorus concentrations in water are reduced during the growing season due to plant uptake but decomposition and subsequent mineralisation of organic matter releases phosphorus over the winter and accounts for the higher winter phosphorus concentrations in the marsh.[18][21]

Retention by soils or root-bed media

Two types of phosphate retention mechanisms may occur in soils or root-bed media: chemical adsorption onto the medium[43] and physical precipitation of the phosphate ion.[44] Both result from the attraction between phosphate ion and ions of Al, Fe or Ca [43][45] and terminates with formation of various iron phosphates (Fe-P), aluminum phosphates (Al-P) or calcium phosphates (Ca-P).[13]

Oxidation-reduction potential (ORP, formally reported as E

h) of soil or water is a measure of its ability to reduce or oxidize chemical substances and may range between -350 and +600 millivolts (mV). Though redox potential does not affect phosphorus' oxidation state, redox potential is indirectly important because of its effect on iron solubility (through reduction of ferric oxides). Severely reduced conditions in the sediments may result in phosphorus release,[46] Typical wetland soils may have an E

h of -200 mV.[47] Under these reduced conditions Fe3+

(Ferric iron) in insoluble ferric oxides may be reduced to soluble Fe2+

(Ferrous iron). Any phosphate ion bound to the ferric oxide may be released back into solution as it dissolves[14][44] However, the Fe2+

diffusing in the water column may be re-oxidized to Fe3+

and re-precipitated as an iron oxide when it encounters oxygenated surface water. This precipitation reaction may remove phosphate from the water column and deposit it back on the surface of sediments .[22] Thus, there can be a dynamic uptake and release of phosphorus in sediments that is governed by the amount of oxygen in the water column. A well documented occurrence in the hypolimnion of lakes is the release of soluble phosphorus when conditions become anaerobic.[48][49] This phenomenon also occurs in natural wetlands. Oxygen concentrations of less than 2.0 mg/l result in the release of phosphorus from sediments.[50][51]

Phosphorus removal from domestic sewage

Adsorption to binding sites within sediments was the major phosphorus removal mechanism in the surface flow constructed wetland system at Port Perry, Ontario[52] Release of phosphorus from the sediments occurred when anaerobic conditions prevailed. The lowest wetland effluent phosphorus levels occurred when oxygen levels of the overlying water column were above 1.0 mg / L. Removal efficiencies for total phosphorus were 54-59% with mean effluent levels of 0.38 mg P/L. Wetland effluent phosphorus concentration was higher than influent levels during the winter months.

The phosphorus removed in a VF wetland in Australia over a short term was stored in the following wetland components in order of decreasing importance: substratum> macrophyte >biofilm, but over the long term phosphorus storage was located in macrophyte> substratum>biofilm components. Medium iron-oxide adsorption provides additional removal for some years.[53]

A comparison of phosphorus removal efficiency of two large-scale, surface flow wetland systems in Australia which had a gravel substratum to laboratory phosphorus adsorption indicated that for the first two months of wetland operation, the mean phosphorus removal efficiency of system 1 and 2 was 38% and 22%, respectively. Over the first year a decline in removal efficiencies occurred. During the second year of operation more phosphorus came out than was put in. This release was attributed to the saturation of phosphorus binding sites. Close agreement was found between the phosphorus adsorption capacity of the gravel as determined in the laboratory and the adsorption capacity recorded in the field.

The phosphorus adsorption capacity of a subsurface flow constructed wetland system containing a predominantly quartz gravel in the laboratory using the Langmuir adsorption isotherm was 25 mg P/g gravel.[32] Close agreement between calculated and realized phosphorus adsorption was found. The poor adsorption capacity of the quartz gravel implied that plant uptake and subsequent harvesting were the major phosphorus removal mechanism.[54]

Metals removal

Constructed wetlands have been used extensively for the removal of dissolved metals and metalloids. Although these contaminants are prevalent in mine drainage, they are also found in stormwater, landfill leachate and other sources (e.g., leachate or FDG washwater at coal-fired power plants), for which treatment wetlands have been constructed for mines,[55] and other applications.[56]

Mine water—Acid drainage removal

A seminal publication was a 1994 report from the US Bureau of Mines [57] described the design of wetlands for treatment of acid mine drainage from coal mines. This report replaced the existing trial-and-error process with a strong scientific approach. This legitimized this technology and was followed in treating other contaminated waters.

Designs

Design characteristics

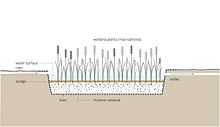

- Surface flow Constructed Wetlands: characterized by the horizontal flow of wastewater across the roots of the plants. They are being phased out due to the large land-area requirements to purify water—20 square metres (220 sq ft) per person—and the increased smell and poor purification in winter.[4]

- Subsurface flow Constructed Wetlands: the flow of wastewater occurs between the roots of the plants and there is no water surfacing (kept below gravel). As a result the system is more efficient, doesn't attract mosquitoes, is less odorous and less sensitive to winter conditions. Also, less area is needed to purify water—5–10 square metres (54–108 sq ft). A downside to the system are the intakes, which can clog easily, although some larger sized gravel will often bypass this problem.[4][58] For large applications, they are often used in combination with vertical flow constructed wetlands. In warm climate, for organic loaded sewage, they require about 3.5 m2 / 150 L for black and grey water combined, with an average water level of 0.50 m. In cold climate they will require the double size (7 m2/150 L). For blackwater treatment only, they will require 2 m2 /50 L in warm weather.

- Vertical flow Constructed Wetlands: these are similar to subsurface flow constructed wetlands but the flow of water is vertical instead of horizontal and the water goes through a mix of media (generally four different granulometries), it requires less space than SF but is dependent on an external energy source. Intake of oxygen into the water is better (thus bacteria activity increased), and pumping is pulsed to reduce obstructions within the intakes. The increased efficiency requires only 3 square metres (32 sq ft) of space per person.[4]

Plants and other organisms

Plants

.jpg)

.jpg)

Although the majority of constructed wetland designers have long relied principally on Typhas and Phragmites, both species are extremely invasive, although effective. The field is currently evolving however towards greater biodiversity.

In North America, cattails (Typha latifolia) are common in constructed wetlands because of their widespread abundance, ability to grow at different water depths, ease of transport and transplantation, and broad tolerance of water composition (including pH, salinity, dissolved oxygen and contaminant concentrations). Elsewhere, Common Reed (Phragmites australis) are common (both in blackwater treatment but also in greywater treatment systems to purify wastewater). In self-purifying water reservoirs (used to purify rainwater) however, certain other plants are used as well. These reservoirs firstly need to be dimensioned to be filled with 1/4 of lavastone and water-purifying plants to purify a certain water quantity.[59]

They include a wide variety of plants, depending on the local climate and location. Plants are usually indigenous in that location for ecological reasons and optimum workings. Plants that supply oxygen and shade are also added in to complete the ecosystem.

The plants used (placed on an area 1/4 of the water mass) are divided in four separate water depth-zones:

- 0–20 cm: Yellow Iris (Iris pseudacorus), Simplestem Bur-reed (Sparganium erectum); may be placed here (temperate climates)

- 40–60 cm: Water Soldier (Stratiotes aloides), European Frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae); may be placed here (temperate climates)

- 60–120 cm: European White Waterlily (Nymphaea alba); may be placed here (temperate climates)

- Below 120 cm: Eurasian Water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum); may be placed here (temperate climates)

The plants are usually grown on coco peat.[60] At the time of implantation to water-purifying ponds, de-nutrified soil is used to prevent unwanted algae and other organisms from taking over.

Fish and bacteria

Locally grown bacteria and non-predatory fish can be added to surface flow constructed wetlands to eliminate or reduce pests, such as mosquitos. The bacteria are usually grown locally by submerging straw to support bacteria arriving from the surroundings. Three types of (non-predatory) fish are chosen to ensure that the fish can coexist: surface; middle-ground swimmers; and bottom swimmers.

Examples of three types (for temperate climates) are:

- Surface swimming fish: Common dace (Leuciscus leuciscus), Ide (Leuciscus idus), common rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus)

- Middle-swimmers: Common roach (Rutilus rutilus)

- Bottom-swimming fish: Tench (Tinca tinca)

Costs

Since constructed wetlands are self-sustaining their lifetime costs are significantly lower than those of conventional treatment systems. Often their capital costs are also lower compared to conventional treatment systems.[1]

Society and Culture

Subsurface flow CWs with sand filter bed have their origin in Europe and are now used all over the world. Subsurface flow CWs with a gravel bed are mainly found in North Africa, South Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand.[2]

Examples

Australia

The Urrbrae Wetland in Australia was constructed for urban flood control and environmental education. International wastewater management programs can be seen from Kolkata (Calcutta), India to Arcata, California, USA.[61]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constructed wetland. |

References

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council (ITRC) (2003): Technical and Regulatory Guidance Document for Constructed Treatment Wetlands.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 Hoffmann, H., Platzer, C., von Münch, E., Winker, M. (2011). Technology review of constructed wetlands - Subsurface flow constructed wetlands for greywater and domestic wastewater treatment. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany

- ↑ "Bio-enhanced Treatment Wetlands (BETS) (Constructed Wetlands)" (PDF). LaGrange County Health Department. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 van Oirschot et al. 2002

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tilley, E., Ulrich, L., Lüthi, C., Reymond, Ph., Zurbrügg, C. Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies - (2nd Revised Edition). Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-906484-57-0.

- ↑ Choudhary et al. (2011) Removal of chlorinated resin and fatty acids from paper mill wastewater through constructed wetland. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 56, 67-71, August.

- ↑ Choudhary et al. (2011) Performance of constructed wetland for the treatment of pulp and paper mill wastewater. Proceedings of World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2011: Bearing Knowledge for Sustainability, Palm Springs, California, USA, p-4856-4865, 22–26 May.

- ↑ Reedbed and Flowform cascade polishing, Sheepdrove Organic Farm, England

- ↑ "Pictures of hybrid reed bed systems". Pure-milieutechniek.be. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ Hammer 1989

- ↑ Hammer 1989, pp. 565–573 Brix, H.; Schierup, H. "Danish experience with sewage treatment in constructed wetlands".

- ↑ Davies & Hart 1990

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Fried & Dean 1955

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sah & Mikkelson 1986

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Patrick & Reddy 1976, pp. 469–472

- ↑ Mitsch & Gosselink 1993

- ↑ Gray, N.F. (1989). Biology of wastewater treatment. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 828.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Mitsch & Gosselink 1986, p. 536

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Keeney 1973

- ↑ Brock & Madigan 1991

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Klopatek 1978

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Wetzel 1983, pp. 255–297

- ↑ Bandurski 1965

- ↑ Nielson et al. 1990

- ↑ Richardson, et al. 1978

- ↑ US EPA, 1988

- ↑ Reed 1995

- ↑ Smith et al. 1997

- ↑

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Guntensbergen, Stearns & Kadlec 1989

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Bernard & Solsky 1976

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Breen 1990

- ↑ Rogers, Breen & Chick 1991

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Sloey, W.E.; Spangler, F.L.; Fetter, Jr, C.W. "Management of freshwater wetlands For nutrient assimilation". pp. 321–340. In Good, Whigham & Simpson 1978

- ↑ Thut 1989

- ↑ Moss 1988

- ↑ Swindell 1990

- ↑ Richardson 1985

- ↑ Pride et al. 1990

- ↑ Conley et al. 1991

- ↑ Kramer, J.R.; Herbes, S.E.; Allen, H.E. (1972). "Phosphorus: analysis of water, biomass, and sediment". In Kramer & Allen 1972, pp. 51–101

- ↑ Simpson, R.L.; Whigham, D.F. "Seasonal patterns of nutrient movement in a freshwater tidal marsh". In Good, Whigham & Simpson 1978, pp. 243–257

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Hsu 1964

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Faulkner, S.P.; Richardson, C.J. (1989). "Physical and chemical characteristics of freshwater wetland soils". In Hammer 1989, pp. 41–131

- ↑ Cole, Olsen & Scott 1953, pp. 352–356

- ↑ Mann 1990, pp. 97–105

- ↑ Hammer 1992, pp. 298

- ↑ Burns, N.M.; Ross, C. (1972). Oxygen-nutrient relationships within the central basin of lake Erie. In Kramer & Allen 1972, pp. 193–250

- ↑ Williams, J.D.H.; Mayer, T. (1972). "Effects of sediment diagenesis and regeneration of phosphorus with special reference to lakes Erie and Ontario". In Kramer & Allen 1972, pp. 281–315

- ↑ Gosselink, J.G.; Turner, R.E. "The role of hydrology in freshwater wetland ecosystems". In Good, Whigham & Simpson 1978, pp. 63–78

- ↑ Kramer & Allen 1972

- ↑ Snell 1990

- ↑ Lantzke et al. 1999

- ↑ Lloyd R. Rozema, M.Sc. (excerpt from Master of Science thesis, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, 2000)

- ↑ "Wetlands for Treatment of Mine Drainage". Technology.infomine.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑

- ↑ Hedin, Nairn & Kleinmann 1994

- ↑ "Constructed Wetlands to Treat Wastewater" (PDF). Wastewater Gardens. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ↑ "LavFilters". Retrieved 2008-06-18.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Coconut growing medium used for water purifying plants

- ↑ "Arcata, California Constructed Wetland: A Cost-Effective Alternative for Wastewater Treatment". Ecotippingpoints.org. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

Citations

- Bernard, J.M.; Solsky, B.A. (1976). "Nutrient cycling in a Carex lacustris wetland". Canadian Journal of Botany 55 (6): 630–638. doi:10.1139/b77-077.

- Bhamidimarri, R; Shilton, A.; Armstrong, I.; Jacobsen, P.; Scarlet, D. (1991). "Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: the New Zealand experience". Water Science Technology 24: 247–253.

- Bowmer, K.H. (1987). "Nutrient removal from effluents by an artificial wetland: influence of rhizosphere aeration and preferential flow studied using bromide and dye tracers". Water Research 21 (5): 591–599. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(87)90068-6.

- Breen, P.F. (1990). "A mass balance method for assessing the potential of artificial wetlands for wastewater treatment". Water Research 24 (6): 689–697. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(90)90024-Z.

- Brix, Hans (1994). "Use of constructed wetlands in water pollution control: Historical development, present status, and future perspectives". Water Science & Technology 30 (8): 209–223.

- Burgoon, P.S.; Reddy, T.A. DeBusk. "Domestic wastewater treatment using emergent plants cultured in gravel and plastic substrates".

In Hammer 1989, pp. 536–541

- Burgoon, P.S.; Reddy, K.R.; DeBusk, T.A.; Koopman, Ben (1991). "Vegetated submerged beds with artificial substrates II: N and P removal". Journal of Environmental Engineering 117 (4): 408–422. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(1991)117:4(408).

- Cole, C.V.; Olsen, S.R.; Scott, C.O. (1953). "The nature of phosphate sorption by calcium carbonate". Soil Science Society of America Proceedings 410.

- Cole, Stephen (1998). "The emergence of treatment wetlands". Environmental Science & Technology 32 (9): 218–223. doi:10.1021/es9834733.

- Conway, T.E.; Murtha, J. M. (1989). "The Iselin marsh pond meadow In Hammer 1989, pp. 139–140".

- Davies, T.H.; Hart, B.T. (1990). "Use of aeration to promote nitrification in reed beds treating wastewater". Advanced Water Pollution Control 11: 77–84. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-040784-5.50012-7. ISBN 9780080407845.

- Finlayson, M.C.; Chick, A.J. (1983). "Testing the significance of aquatic plants to treat abattoir effluent". Water Research 17: 15–422.

- Fried, M.; Dean, L.A. (1955). "Phosphate retention by iron and aluminum in cation exchange systems". Soil Science Society of America Proceedings: 143–47.

- Good, R.E.; Whigham, D.F.; Simpson, R.L., eds. (1978). Freshwater wetlands, ecological processes and management potential. New York: Academic Press.

- Gelt, Joe (1997). "Constructed Wetlands: Using Human Ingenuity, Natural Processes to Treat Water, Build Habitat". ARROYO 9 (4).

- Guntensbergen, G.R.; Stearns, F.; Kadlec, J.A. (1989). "Wetland vegetation". In Hammer 1989, pp. 73–88

- Hammer, D.A. (1992). "Creating freshwater wetlands Lewis Publishers". Chelsea, MI.

- Hammer, D.A., ed. (1989). Constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment. Chelsea, Michigan: Lewis publishers.

- Hammer, D.A.; Bastion, R.K. (1989). "Wetlands ecosystems: Natural water purifiers?". In Hammer 1989, pp. 5–20

- Hedin, R.S.; Nairn, R.W.; Kleinmann, R.L.P. (1994). "Passive treatment of coal mine drainage". Information Circular (Pittsburgh, PA.: U.S. Bureau of Mines) (9389).

- Herskowitz, J. (1986). "Listowell artificial marsh project report" (128 RR,). Ontario Ministry of the Environment project. p. 253.

- Hoffmann, H.; Platzer, C.; von Münch, E.; Winker, M. (2011). "Technology review of constructed wetlands - Subsurface flow constructed wetlands for greywater and domestic wastewater treatment". Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany.

- Hsu, P.H. (1964). "Adsorption of phosphate by aluminum and iron in soils". Soil Science Society of America Proceedings 9: 474–478.

- Jenssen, P.D., T.; Maehlum, T. Zhu; Warner, W.S. (1992). "Cold-climate constructed wetlands". Aas, Norway: JORDFORSK Centre for Soil and Environmental Research, N-1432.

- Kadlec, R.H. (1989). "Hydrologic factors in wetland water treatment". In Hammer 1989, pp. 21– 40

- Kadlec, R. H. (1995). "Wetland treatment at Listowel (revisited) unpublished".

- Klopatek, J.M. (1978). "Nutrient dynamics of Freshwater Riverine marshes and the role of emergent macrophytes". In Good, Whigham & Simpson 1978, pp. 195–217

- Kotz, J.C.; Purcell, K.F. (1987). "Chemistry and chemical reactivity". New York, N.Y.: CBS College Publishing.

- Kramer, J.R.; Allen, H.E., eds. (1972). Nutrients in natural waters John. Toronto: Wiley and Sons.

- Lantzke, I.R.; Mitchell, D.S.; Heritage, A.D.; Sharma, K.P. (1999). "A model controlling orthophosphate removal in planted vertical flow wetlands". Ecological Engineering 12: 93–105. doi:10.1016/S0925-8574(98)00056-1.

- Lemon, E. R.; Smith, I.D. (October 1993). "Sewage waste amendment marsh process (SWAMP) Interim report,".

- Lemon, E.R., G.; Bis.; Braybrook, T.; Rozema, L.; Smith, I. (1997). "Sewage waste amendment marsh process (SWAMP) Final report".

- Mann, R.A. (1990). "Phosphorus removal by constructed wetlands: substratum adsorption". Advanced Water Pollution Control 11 h.

- Mitsch, J.W.; Gosselink, J.G. (1986). Wetlands. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- Moss, B. (1988). "Ecology of freshwater Blackball Scientific Publishers". London.

- Nichols, D.S.; Boelter, D.H. (1982). "Treatment of secondary sewage with a peat-sand filter bed". Journal Environmental Quality 11 (1).

- Niering, W.A. (1988). "Wetlands: Audubon society nature guide". Toronto: Random House of Canada Limited. p. 638.

- Ontario Ministry of the Environment (1994). "Storm water management practices planning and design manual". O.B.C.-Ontario Building Code Act (Queen's Printer for Ontario): 8–14.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Patrick, W.H., Jr.; Reddy, K.R. (1976). "Nitrification-denitrification in flooded soils and water bottoms: dependence on oxygen supply and ammonium diffusion". Journal of Environmental Quality 5.

- Reddy, K.R.; DeBusk, W.F. (1987). Reddy and, K.R.; Smith, W.H., eds. "Nutrient storage capabilities of aquatic and wetland plants". Aquatic plants for water treatment and resource recovery (Magnolia Publishing Inc).

- Reed, S.C. (1986). "In Appropriate Wastewater Management Technologies for Rural Areas Under Adverse Conditions". Tech Press (Halifax, N.S): 207–219.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Reed, S.C. (1991). "Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment". BioCycle (January): 44–49.

- Reed, S.C. (1995). "Natural systems for waste management and treatment". McGraw Hill, Inc.

- Reed, S.C.; Brown, D. (1995). "Subsurface flow wetlands-a performance evaluation". Water Environmental Research 67 (2): 244–248. doi:10.2175/106143095X131420.

- Rogers, K.H.; Breen, P.F.; Chick, A.J. (1991). "Nitrogen removal in experimental wetland treatment systems: evidence for the role of aquatic plants". Research Journal Water Political Control Fed 63: 934–941.

- Rozema, L.R. , G.N.; Bis, T. Braybrook, E, R, Lemon; Smith, I. (1996). "Retention of phosphorus in a Sub-surface flow constructed wetland Presented at: The 31st central Canadian symposium on water pollution research, Burlington, Ontario".

- Sah, R.N.; Mikkelson, D. (1986). "Transformations of inorganic phosphorus during the flooding and draining cycles of soil". American Journal Soil Science 50: 62–67. doi:10.2136/sssaj1986.03615995005000010012x.

- Smith, I.; Bis, G.N.; Lemon, E.R.; Rozema, L.R. (1997). "A thermal analysis of a vertical flow constructed wetland". Water Science Technology 35 (5): 55–62. doi:10.1016/S0273-1223(97)00052-8.

- Snell, D. (1990). "Port Perry artificial marsh sewage treatment system unpublished report".

- Steiner, R.S.; Freeman Configuration and substrate design considerations for constructed wetlands wastewater treatment, R.J. Missing or empty

|title=(help) In Hammer 1989, pp. 363–377 - Tanner, C. C., J. S.; Clayton, John S.; Upsdell, M.P. (199). "Effect of loading rate and planting on treatment of dairy farm wastewater’s in constructed wetlands-II removal of nitrogen phosphorus". Water Research 29: 27–34. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(94)00140-3.

- Thut, N.R. (1989). "Utilisation of artificial marshes for treatment of pulp mill effluents". In Hammer 1989, pp. 239–251

- United States environmental protection agency. (1988). "Design manual: constructed wetlands and aquatic plant systems for municipal wastewater treatment EPA/625/1- 88/022". p. 83.

- van Oirschot, Dion; Zaakvoerder; Rietland; Poppel (2002). "Certificering van plantenwaterzuiveringssystemen" (PDF) (in German). Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- Watson, J.T.; Reed, S.C.; Kadlec, R.H.; Knight, R.L.; Whitehouse, A.E. "Performance expectations and loading rates for constructed wetlands". In Hammer 1989, pp. 319–353

- Weber, L.R. (1990). "Ontario soils Physical, chemical and biological properties and soil management practices—A reprint of Ontario Soils". Guelph, Ontario: Faculty and Staff of the Department of Land Resources Science Ontario Agricultural College University of Guelph.

- Wetzel, R.G. (1983). Limnology. Orlando, Florida: Saunders college publishing.

- University of Alaska Agriculture and Forestry Station (2005). "Wetlands and wastewater treatment in Alaska". Agroborealis 36 (2).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constructed wetland. |

- American Society of Professional Wetland Engineers website—a wetland restoration for habitat and treatment wiki

- U.S.EPA: Constructed Wetlands resources website—United States Environmental Protection Agency

- EPA Constructed Wetlands resources—Handbook, studies and related resources

- Publications on constructed wetlands in the library of the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||