Connecticut Colony

| Colony of Connecticut | |||||

| Colony of England (1636–1707) Colony of Great Britain (1707–76) | |||||

| |||||

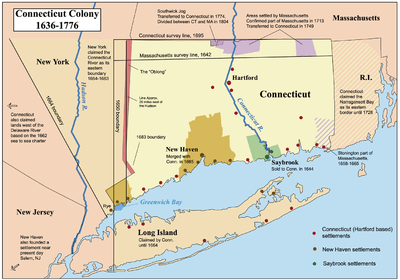

A map of the Connecticut, New Haven, and Saybrook colonies. | |||||

| Capital | Hartford (1636–1776) New Haven (joint capital with Hartford, 1701–76) | ||||

| Languages | English, Mohegan-Pequot, Quiripi | ||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||

| Legislature | General Court of the Colony of Connecticut | ||||

| History | |||||

| - | Established | 1636 | |||

| - | Independence | 1776 | |||

| Currency | Pound sterling | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in North America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settlement for a Puritan congregation. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English had permanently gained control of the colony later in the year of 1636. The colony was later the scene of a bloody and raging war between the English and Native Americans, known as the Pequot War. It played a significant role in the establishment of self-government in the New World with its refusal to surrender local authority to the Dominion of New England, an event known as the Charter Oak incident which occurred at Jeremy Adams' inn & tavern.

Two other English colonies in the present-day state of Connecticut were merged into the Colony of Connecticut: Saybrook Colony in 1644 and New Haven Colony in 1662.

Leaders

Thomas Hooker, a prominent Puritan minister, and Governor John Haynes of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who led 100 people to present day Hartford in 1636, are often considered the founders of the Connecticut colony. The sermon Hooker delivered to his congregation on the principles of government on May 31, 1638 influenced those who would write the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut later that year. The Fundamental Orders may have been drafted by Roger Ludlow of Windsor, the only trained lawyer living in Connecticut in the 1630s, and were transcribed into the official record by the secretary, Thomas Welles.

The Rev. John Davenport and merchant Theophilus Eaton are considered the founders of the New Haven Colony, which would be absorbed into Connecticut Colony in the 1660s.

In the colony's early years, the governor could not serve consecutive terms. Thus, for twenty years, the governorship often rotated between John Haynes and Edward Hopkins, both of whom were from Hartford. George Wyllys, Thomas Welles, and John Webster, also Hartford men, sat in the governor's chair for brief periods in the 1640s and 1650s.

John Winthrop the Younger of New London, the son of the founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, played an important role in consolidating separate settlements on the Connecticut River into a single colony; and he served as Governor of Connecticut from 1659 to 1675. Winthrop was also instrumental in obtaining the colony's 1662 charter, which incorporated New Haven into Connecticut. His son, Fitz-John Winthrop, would also govern the colony for ten years, starting in 1698.

Roger Ludlow was an Oxford-educated lawyer and former Deputy Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who petitioned the General Court for rights to settle the area. Ludlow led the March Commission in settling disputes over land rights. He is credited as drafting the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1650) in collaboration with Hooker, Winthrop, and others. Ludlow was the first Deputy Governor of Connecticut.

William Leete of Guilford served as governor of New Haven Colony before that colony's merger into Connecticut, and as governor of Connecticut following John Winthrop, Jr's death in 1675. He is the only man to serve as governor of both New Haven and Connecticut.

Robert Treat of Milford served as governor of the colony both prior to and after its inclusion in Sir Edmund Andros's Dominion of New England. His father, Richard Treat, was one of the original patentees of the colony.

The colony enjoyed a string of strong governors in the 18th century, many being re-elected yearly until they died. Upon the death of Fitz-John Winthrop, Gurdon Saltonstall, Winthrop's minister in New London, was elected governor. Saltonstall was the only minister to serve as governor of Connecticut, and he belies the common misconception that Puritan clergy could not hold political office. Upon Saltonstall's death, Deputy Governor Joseph Talcott of Hartford became governor. Deputy Governor Jonathan Law of Milford succeeded to the position of governor upon Talcott's death. When Jonathan Law died, Deputy Governor Roger Wolcott of Windsor became governor. Wolcott, the father of Declaration of Independence signer Oliver Wolcott, was voted out of office in 1754 for his role in the Spanish Ship Case. Wolcott's successor, Thomas Fitch of Norwalk, guided the colony through the Seven Years' War, but was, himself, voted out of office in 1766 for not being strong enough in his repudiation of the Stamp Act. William Pitkin of Hartford (now East Hartford), the man who defeated Fitch, was a leader in the Sons of Liberty and also the cousin of former governor Roger Wolcott. Pitkin died in office in 1769, and was replaced by Deputy Governor Jonathan Trumbull, a merchant from Lebanon. Trumbull, also a supporter of the Sons of Liberty, continued to be elected governor throughout the American Revolutionary War and retired as governor in 1784, the year after the signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which granted the United States its independence from Great Britain.

Economic and social history

The economy began with subsistence farming in the 17th century, and developed with greater diversity and an increased focus on production for distant markets, especially the British colonies in the Caribbean. The American Revolution cut off imports from Britain, and stimulated a manufacturing sector that made heavy use of the entrepreneurship and mechanical skills of the people. In the second half of the 18th century, difficulties arose from the shortage of good farmland, periodic money problems, and downward price pressures in the export market. In agriculture there was a shift from grain to animal products.[1] The colonial government from time to time attempted to promote various commodities such as hemp, potash, and lumber as export items to bolster its economy and improve its balance of trade with Great Britain.[2]

Connecticut's domestic architecture included a wide variety of house forms. They generally reflected the dominant English heritage and architectural tradition.[3]

See also

Further reading

- Andrews, Charles M. The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements, volume 2 (1936) pp 67–194, by leading scholar

- Atwater, Edward Elias (1881). History of the Colony of New Haven to Its Absorption Into Connecticut. author. to 1664

- Burpee, Charles W. The story of Connecticut (4 vol 1939); detailed narrative in vol 1-2

- Clark, George Larkin. A History of Connecticut: Its People and Institutions (1914) 608 pp; based on solid scholarship online

- Federal Writers' Project. Connecticut: A Guide to its Roads, Lore, and People (1940) famous WPA guide to history and to all the towns online

- Fraser, Bruce. Land of Steady Habits: A Brief History of Connecticut (1988), 80 pp, from state historical society

- Hollister, Gideon Hiram (1855). The History of Connecticut: From the First Settlement of the Colony to the Adoption of the Present Constitution. Durrie and Peck., vol. 1 to 1740s

- Jones, Mary Jeanne Anderson. Congregational Commonwealth: Connecticut, 1636-1662 (1968)

- Roth, David M. and Freeman Meyer. From Revolution to Constitution: Connecticut, 1763-1818 (Series in Connecticut history) (1975) 111pp

- Sanford, Elias Benjamin (1887). A history of Connecticut.; very old textbook; strongest on military history, and schools

- Taylor, Robert Joseph. Colonial Connecticut: A History (1979); standard scholarly history

- Trumbull, Benjamin (1818). Complete History of Connecticut, Civil and Ecclesiastical. very old history; to 1764

- Van Dusen, Albert E. Connecticut A Fully Illustrated History of the State from the Seventeenth Century to the Present (1961) 470pp the standard survey to 1960, by a leading scholar

- Van Dusen, Albert E. Puritans against the wilderness: Connecticut history to 1763 (Series in Connecticut history) 150pp (1975)

- Zeichner, Oscar. Connecticut's Years of Controversy, 1750-1776 (1949)

Specialized studies

- Buell, Richard, Jr. Dear Liberty: Connecticut's Mobilization for the Revolutionary War (1980), major scholarly study

- Bushman, Richard L. (1970). From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. Harvard University Press.

- Collier, Christopher. Roger Sherman's Connecticut: Yankee Politics and the American Revolution (1971)

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Economic Development in Colonial and Revolutionary Connecticut: An Overview," William and Mary Quarterly (1980) 37#3 pp. 429–450 in JSTOR

- Daniels, Bruce Colin. The Connecticut town: Growth and development, 1635-1790 (Wesleyan University Press, 1979)

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Democracy and Oligarchy in Connecticut Towns-General Assembly Officeholding, 1701-1790" Social Science Quarterly (1975) 56#3 pp: 460-475.

- Fennelly, Catherine. Connecticut women in the Revolutionary era (Connecticut bicentennial series) (1975) 60pp

- Grant, Charles S. Democracy in the Connecticut Frontier Town of Kent (1970)

- Hooker, Roland Mather. The Colonial Trade of Connecticut (1936) online; 44pp

- Lambert, Edward Rodolphus (1838). History of the Colony of New Haven: Before and After the Union with Connecticut. Containing a Particular Description of the Towns which Composed that Government, Viz., New Haven, Milford, Guilford, Branford, Stamford, & Southold, L. I., with a Notice of the Towns which Have Been Set Off from "the Original Six.". Hitchcock & Stafford.

- Main, Jackson Turner. Connecticut Society in the Era of the American Revolution (pamphlet in the Connecticut bicentennial series) (1977)

- Pierson, George Wilson. History of Yale College (vol 1, 1952) scholarly history

- Selesky Harold E. War and Society in Colonial Connecticut (1990) 278 pp.

- Taylor, John M. The Witchcraft Delusion in Colonial Connecticut, 1647-1697 (1969) online

- Trumbull, James Hammond (1886). The memorial history of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633-1884. E. L. Osgood., 700pp

Historiography

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Antiquarians and Professionals: The Historians of Colonial Connecticut," Connecticut History (1982), 23#1, pp 81–97.

- Meyer, Freeman W. "The Evolution of the Interpretation of Economic Life in Colonial Connecticut," Connecticut History (1985) 26#1 pp 33–43.

References

- ↑ Bruce C. Daniels, "Economic Development in Colonial and Revolutionary Connecticut: An Overview," William and Mary Quarterly (1980) 37#3 pp. 429-450 in JSTOR

- ↑ P. Bradley Nutting, "Colonial Connecticut's Search for a Staple: A Mercantile Paradox," New England Journal of History (2000) 57#1 pp 58-69.

- ↑ Ann Y. Smith, "A New Look at the Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut," Connecticut History (2007) 46#1 pp 16-44

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Colony of Connecticut. |

Archival collections

- Guide to the Connecticut Colony Land Deeds. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

Other

- Colonial Connecticut Records: The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, 1636-1776

- Colonial Connecticut Town Nomenclature

- Connecticut Constitutionalism, 1639-1789

- Timeline of Colonial Connecticut History

Coordinates: 41°43′05″N 72°45′05″W / 41.71803°N 72.75146°W