Connacht

| Connaught Connacht[1] | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

| Coordinates: 53°47′N 9°03′W / 53.78°N 9.05°WCoordinates: 53°47′N 9°03′W / 53.78°N 9.05°W | ||

| State |

| |

| Counties |

Galway Leitrim Mayo Roscommon Sligo | |

| Government | ||

| • Teachta Dála |

12 Fine Gael TDs 3 Fianna Fáil TDs 2 Labour Party TDs 2 Independent TDs 1 Sinn Féin TD | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 17,788 km2 (6,867 sq mi) | |

| Population (2011)[2] | ||

| • Total | 542,547 | |

| ISO 3166 code | IE-C | |

| Patron Saint: Kieran the Younger[3] | ||

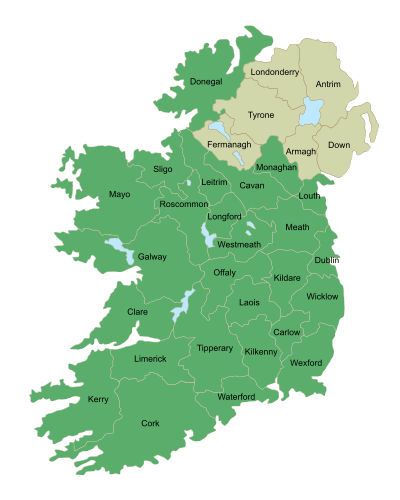

Connacht or Connaught[1] /ˈkɒnəkt/[4] (Irish: Connacht[1] or Cúige Chonnacht) is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the west of the country. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" (in Irish: rí ruirech).

The province of Connacht has the greatest number of native Irish speakers at between 5–10% (40,000–55,000) of the population. There are several important Irish-speaking areas in Counties Galway and Mayo.

Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes. In later centuries, local government legislation has seen further sub-division of the historic counties. The province of Connacht has no official function for local government purposes, but it is an officially recognised subdivision of the Irish state. It is listed on ISO-3166-2 as one of the four provinces of Ireland and "IE-C" is attributed to Connacht as its country sub-division code. Along with counties from other provinces, Connacht lies in the Midlands-North-West constituency for elections to the European Parliament.

Irish language

The Irish language is spoken in the Gaeltacht areas of Counties Mayo and Galway, the largest being in the west of County Galway. The Galway Gaeltacht is the largest Irish-speaking region in Ireland covering Cois Fharraige, parts of Connemara, Conamara Theas, Aran Islands, Dúithche Sheoigeach and Galway City Gaeltacht. Irish-speaking areas in County Mayo can be found in Iorras, Acaill and Tourmakeady. According to the 2011 census Irish is spoken outside of the education system on a daily basis by 14,600 people.[2]

There are between 40,000–55,000 Irish speakers in the province, over 30,000 in Galway and more than 6,000 in Mayo. There is also the 4,265 attending the 18 Gaelscoils (Irish language primary schools) and three Gaelcholáiste (Irish language secondary schools) outside the Gaeltacht across the province. Between 7% and 10% of the province are either native Irish speakers from the Gaeltacht, in Irish medium education or native Irish speakers who no longer live in Gaeltacht areas but still live in the province.

See also:

Geography and political divisions

The province is divided into five counties; Galway, Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon and Sligo. It is the smallest of the four Irish provinces, with a population of 542,547. Galway is the only city.

Physical geography

The highest point of Connacht is Mweelrea (814 m), in County Mayo. The largest island in Connacht (and Ireland) is Achill. The biggest lake is Lough Corrib.

Much of the west coast (e.g. Connemara and Erris) is ruggedly inhospitable and not conducive for agriculture. It contains the main mountainous areas in Connacht, including the Twelve Bens, Maumturks, Mweelrea, Croagh Patrick, Nephin Beg, Ox Mountains, and Dartry Mountains.

Killary Harbour, one of only three fjords in Ireland, is located at the foot of Mweelrea. Connemara National Park is in County Galway. The Aran Islands, featuring prehistoric forts such as Dún Aonghasa, have been a regular tourist destination since the 19th century.

Inland areas such as east Galway, Roscommon and Sligo have enjoyed greater historical population density due to better agricultural land and infrastructure.

Rivers and lakes include the River Moy, River Corrib, the Shannon, Lough Mask, Lough Melvin, Lough Allen and Lough Gill.

The largest urban area in Connacht is Galway, with a population of 76,778. Other large towns in Connacht are Sligo (19,452), Castlebar (12,318) and Ballina (11,086).

Largest settlements (2011)

| # | Settlement | County | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Galway | County Galway | 76,778 |

| 2 | Sligo | County Sligo | 20,000 |

| 3 | Castlebar | County Mayo | 12,318 |

| 4 | Ballina | County Mayo | 10,361[5] |

| 5 | Tuam | County Galway | 8,242 |

| 6 | Ballinasloe | County Galway | 6,659 |

| 7 | Roscommon | County Roscommon | 5,693 |

| 8 | Westport | County Mayo | 5,543[5] |

| 9 | Loughrea | County Galway | 5,062 |

| 10 | Oranmore | County Galway | 4,799 |

| 11 | Carrick-on-Shannon | County Leitrim | 3,980 |

| 12 | Claremorris | County Mayo | 3,979 |

| 13 | Athenry | County Galway | 3,950 |

Name

The name Connacht comes from the medieval ruling dynasty, the Connacht, later Connachta, whose name means "descendants of Conn", from the mythical king Conn of the Hundred Battles. Originally Connacht was a singular collective noun, but it came to be used only in the plural Connachta, partly by analogy with plural names of other dynastic territories like Ulaid and Laigin, and partly because the Connachta split into different branches.[6] Before the Connachta dynasty, the province (cúige, "fifth") was known as Cóiced Ol nEchmacht. In Modern Irish, the province is usually called Cúige Chonnacht, "the Province of Connacht", where Chonnacht is plural genitive case with lenition of the C to Ch.

The usual English spelling in Ireland since the Gaelic revival is Connacht, the spelling of the disused Irish singular. The official English spelling during English and British rule was the anglicisation Connaught, pronounced /kɒnɔːt/ or /kɒnət/.[7] This was used for the Connaught Rangers in the British Army; in the title of Queen Victoria's son Arthur, Duke of Connaught; and the Connaught Hotel, London, named after the Duke in 1917. Usage of the Connaught spelling is now in decline. State bodies use Connacht, for example in Central Statistics Office census reports since 1926,[8] and the name of the Connacht–Ulster European Parliament constituency of 1979–2004,[9][10][11] although Connaught occurs in some statutes.[12][13] Among newspapers, the Connaught Telegraph (founded 1830) retains the anglicised spelling in its name, whereas the Connacht Tribune (founded 1909) uses the Gaelic.

Politics

Connacht–Ulster was one of the Republic of Ireland's four regional constituencies for elections to the European Parliament until it was superseded in 2004 by the constituency of North-West.

Sport in Connacht

Association football

Men's teams

- Galway United F.C. in the League of Ireland Premier Division

- Sligo Rovers F.C. in the League of Ireland Premier Division

Women's teams

- Castlebar Celtic W.F.C. in the National League

- Galway W.F.C. in the National League

Basketball

Men's teams

- Maree Basketball in Division 1 of the Irish League

- Moycullen Basketball in Division 1 of the Irish League

Women's teams

- NUIG Mystics in Division 1 of the Irish League

Rugby union

Men's teams

- Connacht Rugby in the Pro12

- Buccaneers RFC in the All-Ireland League

- Galway Corinthians RFC in the All-Ireland League

- Galwegians RFC in the All-Ireland League

- Sligo RFC in the All-Ireland League

Women's teams

- Connacht Rugby in the Irish Inter-Provincial Championship

- Galwegians RFC in Division 1 of the All-Ireland League

- Sligo RFC in Division 2 North of the All-Ireland League

History

Early history

Up to the early historic era, Connacht then included County Clare, and was known as Cóiced Ol nEchmacht. It is said that the Fir Bolg ruled all of Ireland right before the Tuatha Dé Danann arrived. When the Fir Bolg were defeated, the Tuatha Dé Danann were so touched by the courage of their enemy that they would give them a quarter of Ireland. They chose Connacht.

Sites such as the Céide Fields, Knocknarea, Listoghil, Carrowkeel Megalithic Cemetery and Rathcroghan, all demonstrate intensive occupation of Connacht far back into prehistory.

Enigmatic artefacts such as the Turoe stone and the Castlestrange stone, whatever their purpose, denote the ambition and achievement of those societies, and their contact with the La Tène culture of mainland Europe.

In the early historic era (c. 400-c.500), Ol nEchmacht was not a single unified kingdom. It instead comprised dozens of major and minor túath; rulers of larger túath (Maigh Seóla, Uí Maine, Aidhne and Máenmaige) were accorded high kingly status, while peoples such as the Gailenga, Corco Moga and Senchineoil were lesser peoples given the status of Déisi. All were termed kingdoms, but according to a graded status, denoting each according the likes of lord, count, earl, king.

Some of the more notable peoples included the following:

- Auteini – County Roscommon/County Galway

- Conmaicne – west coast, and northern areas of, County Galway

- Dartraige – north-west County Leitrim

- Delbhna – south County Roscommon, and both sides of the Lough Corrib

- Erdini – County Leitrim/County Cavan

- Fir Craibe – County Clare (then part of Connacht) and south-west Galway

- Fir Domnann – west coast of Mayo

- Gamhanraigh – North Mayo

- Nagnatae – County Sligo

- Soghain – most of east-central County Galway

- Tuatha Taiden – east Galway and south Roscommon

For an extensive list of nations known to have resided in Connacht during this era, see Cóiced Ol nEchmacht.

By the 5th century, the pre-historic tribal polities were giving way to dynasties. Older nations such as the Auteini and Nagnatae – recorded by Ptolemy (c. AD 90–c. 168) in Geography – gave way to dynastic hereditary rule. This is demonstrated in the noun moccu in names such as Muirchu moccu Machtheni, which indicated a person was of the Machtheni people. As evidenced by kings such as Mac Cairthinn mac Coelboth (died 446) and Ailill Molt (died c. 482), even by the 5th century the gens was giving way to kinship all over Ireland, as both men were identified as of the Uí Enechglaiss and Uí Fiachrach dynasties, not of tribes. By 700, moccu had been entirely replaced by mac and hua (later Mac and Ó).

During the mid-8th century, what is now County Clare was absorbed into Thomond by the Déisi Tuisceart. It has remained a part of the province of Munster ever since.

The name Connacht arose from the most successful of these early dynasties, The Connachta. By 1050, they had extended their rule from Rathcroghan in north County Roscommon to large areas of what are now County Galway, County Mayo, County Sligo, County Leitrim. The dynastic term was from then on applied to the overall geographic area containing those counties, and has remained so ever since.

See also:

- Cath Maige Mucrama – epic concerning a battle that took place between Athenry and Clarenbridge

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis – concerning pre-Gaelic languages of Ireland

- Esker Riada – used as one of the principal prehistoric Irish roadways, the Sli Mor,

- Hibernia – Ireland in Greek and Roman accounts

- Insular art – post-Roman native art of Ireland and Great Britain

- Medb – legendary Queen of Connacht

- Táin Bó Cúailnge – Irish epic, partly set in Connacht

- Táin Bó Flidhais – Irish epic, set in Erris

- Trícha cét – Gaelic territorial unit

- Túath – Gaelic social/political division

The Kingdom of Connacht

The most successful sept of the Connachta were the Ó Conchobair of Síol Muireadaigh. They derived their surname from Conchobar mac Taidg Mór (c.800–882), from whom all subsequent Ó Conchobair Kings of Connacht descended.

Conchobar was a nominal vassal of Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid, High King of Ireland (died 862). He married Máel Sechnaill's daughter, Ailbe, and had sons Áed mac Conchobair (died 888), Tadg mac Conchobair (died 900) and Cathal mac Conchobair (died 925), all of whom subsequently reigned. Conchobar and his sons's descendants expanded the power of the Síl Muiredaig south into Ui Maine, west into Iar Connacht, and north into Uí Fiachrach Muaidhe and Bréifne.

By the reign of Áed in Gai Bernaig (1046–1067), Connacht's kings ruled much what is now the province. Yet the Ó Conchobair's contended for control with their cousins, the Ua Ruairc of Uí Briúin Bréifne. Four Ua Ruairc's achieved rule of the kingdom – Fergal Ua Ruairc (956–967), Art Uallach Ua Ruairc (1030–1046, Áed Ua Ruairc(1067–1087) and Domnall Ua Ruairc (1098–1102. In addition, the usurper Flaithbertaigh Ua Flaithbertaigh gained the kingship in 1092 by the expedient of blinding King Ruaidrí na Saide Buide. After 1102 the Ua Ruairc's and Ua Flaithbertaigh's were subborned and confined to their own kingdoms of Bréifne and Iar Connacht. From then till the death of the last king in 1474, the kingship was held exclusively by the Ó Conchobair's.

The single most substantial sub-kingdom in Connacht was Uí Maine, which at it maximum extant enclosed central and south County Roscommon, central, east-central and south County Galway, along with the territory of Lusmagh in Munster. Their rulers bore the surname Ó Cellaigh.

Though the Ó Cellaigh's were never elevated to the provincial kingship, Ui Maine existed as a semi-independent kingdom both before and after the demise of the Connacht kingship. Notable rulers of Ui Maine included

- Máine Mór (c. 357?–407?)

- Marcán mac Tommáin (died 653)

- Tadhg Mór Ua Cellaigh (reigned 985–1014)

- Conchobar Maenmaige Ua Cellaigh (r.1145–1180)

- Tadhg Ó Cellaigh (died 1316)

- William Buidhe Ó Cellaigh (c.1349-c.1381)

- Maelsechlainn mac Tadhg Ó Cellaigh (reigned c. 1499–1511)

Kings and High Kings

Under kings Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair (1088–1156) and his son Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair (c.1120–1198) Connacht became one of the five dominant kingdoms on the island. Tairrdelbach and Ruaidrí became the first men from west of the Shannon to gain the title Ard-Rí na hÉireann (High King of Ireland). In the latter's case, he was recognised all over the island in 1166 as Rí Éireann, or King of Ireland.

Tairrdelbach was highly innovative, building the first stone castles in Ireland, and more controversially, introducing the policy of primogeniture to a hostile Gaelic polity. Castles were built in the 1120s at Galway (where he based his fleet), Dunmore, Sligo and Ballinasloe, where he dug a new six-mile canal to divert the river Suck around the castle of Dun Ló. Churches, monasteries and dioceses were re-founded or created, works such as the Corpus Missal, the High Cross of Tuam and the Cross of Cong were sponsored by him.

Tairrdelbach annexed the Kingdom of Mide; its rulers, the Clann Cholmáin, became his vassals. This brought two of Ireland's five main kingdoms under the direct control of Connacht. He also asserted control over Dublin, which was even then recognised as the national (political).

His son, Ruaidrí, became king of Connacht "without any opposition" in 1156. One of his first acts as king was arresting three of his twenty-two brothers, "Brian Breifneach, Brian Luighneach, and Muircheartach Muimhneach" to prevent them from usurping him. He blinded Brian Breifneach as an extra precaution.

Ruaidrí was compelled to recognise Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn as Ard-Rí, though he went to war with him in 1159. Mac Lochlainn's murder in 1166 left Ruaidrí the unopposed ruler of all Ireland. He was crowned in 1166 at Dublin, "took the kingship of Ireland ...[and was] inaugurated king as honourably as any king of the Gaeidhil was ever inaugurated;" He was the first and last native ruler who was recognised by the Gaelic-Irish as full King of Ireland.

However, his expulsion of Dermot MacMurrough later that year brought about the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Ruaidrí's inept response to events led to rebellion by his sons in 1177, and his deposition by Conchobar Maenmaige Ua Conchobair in 1183.

Ruaidrí died at Cong in 1198, noted as the annals as late "King of Connacht and of All Ireland, both the Irish and the English."

Had the Norman invasion of Ireland not occurred, the Ó Conchobair dynasty may well have established themselves as the royal family of Ireland. The senior head of the clan, the O'Conor Don, is still recognised as the presumptive claimant to the throne of Ireland, should it ever be re-established.

High medieval era

Connacht was first raided by the Anglo-Normans in 1177 but not until 1237 did encastellation begin under Richard Mor de Burgh (c. 1194–1242). New towns were founded (Athenry, Headford, Castlebar) or former settlements expanded (Sligo, Roscommon, Loughrea, Ballymote). Both Gael and Gall acknowledged the supreme lordship of the Earl of Ulster; after the murder of the last earl in 1333, the Anglo-Irish split into different factions, the most powerful emerging as Bourke of Mac William Eighter in north Connacht, and Burke of Clanricarde in the south. They were regularly in and out of alliance with equally powerful Gaelic lords and kings such as Ó Conchobair of Síol Muireadaigh, Ó Cellaigh of Ui Maine and Mac Diarmata of Moylurg, in addition to extraprovincial powers such as Ó Briain of Thomond, FitzGerald of Kildare, Ó Domhnaill of Tír Chonaill.

Lesser lords of both races included Mac Donnchadha, Mac Goisdelbh, Mac Bhaldrin, Mac Siurtain, Ó hEaghra, Ó Flaithbeheraigh, Ó Dubhda, Ó Seachnasaigh, Ó Manacháin, Seoighe, Ó Máille, Ó Ruairc, Ó Madadháin, Bairéad, Ó Máel Ruanaid, Ó hEidhin, Ó Finnaghtaigh, Ó Fallmhain, Breathneach, Mac Airechtaig, Ó Neachtain, Ó hAllmhuráin, Ó Fathaigh.

Independent from both Gael and Gall was the town of Galway, the only significant urban area in the province. After expelling the Burkes of Clanricarde, its inhabitants governed themselves under charter of the king of England. Its merchant families, The Tribes of Galway, traded within Ireland, as well as England, France and Spain till it was reckoned one of Ireland's most eminent towns. It was something of an oddity as it was ruled by a merchant middle class of elected freemen, whereas both Gaelic-Irish and Anglo-Irish lordships were inherited by those of noble blood, or violently seized. Its mayor enjoyed supreme power but only for the length of his office, rarely more than a year. Galway's inhabitants were of mixed descent, its families bearing surnames of Gaelic, French, English, Welsh, Norman and other origins. In contrast to much of the rest of the province, they were literate and multi-lingual and actively sought the protection of the English Crown. They however remained devout Catholics, which displeased the Anglo-Irish administration, and later, the House of Stuart.

Connacht was the site of two of the bloodiest battles in Irish history, the Second Battle of Athenry (1316) and the Battle of Knockdoe (1504). The casualties of both battles were measured in several thousand, unusually high for Irish warfare. A third battle at Aughrim in 1691 resulted in an estimated 10,000 deaths.

All of Connacht's lordships remained in states of full or semi-independence from other Gaelic-Irish and Anglo-Irish rulers till the late 16th century, when the Tudor conquest of Ireland (c. 1534–1603) brought all under the direct rule of King James I of England. The counties were created from c. 1569 onwards.

Confederate and Williamite Wars

During the 17th century representatives from Connacht played leading roles in Confederate Ireland and during the Williamite War in Ireland. Its main town, Galway, endured several sieges (see Sieges of Galway), while warfare, plague, famine and sectarian massacres killed about a third of the population by 1655.

One of the last battles fought in pre-20th century Ireland occurred in Connacht, the Battle of Aughrim on 12 July 1691.

Early modern era

Connacht was mainly at peace between 1691 and 1798. A population explosion in the early 18th century was curbed by the Irish Famine (1740–1741), which led to many deaths and some emigration. Its memory has been overshadowed by the Great Famine (Ireland) one hundred years later.

The Republic of Connacht had a brief existence as a short-lived French client republic established by the French Revolutionary Army and United Irishmen during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.[14][15] It lasted for about 12 days, from 27 August to 8 September, and comprised the northern part of the province of Connacht.

Learned people from the province in this era included the following:

- Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh, Gaelic scribe, translator, historian and genealogist (fl. 1640-1671).

- Richard Lynch, theologian (1611–1676)

- Ruaidhrí Ó Flaithbheartaigh, chronology and antiquarian (1629-c.1718)

- Francis Martin, Professor of Greek and theologian (1652–1722)

- John Fergus, member of Ó Neachtáin literary circle (c.1700-c.1761)

- Tomás Ó Caiside, soldier and poet (c.1709–1733?)

- Charles O'Conor (historian) (1710–1791)

- Count Patrick D'Arcy, mathematician and soldier (1725–1779)

- Richard Kirwan, scientist (1733–1812)

- Riocard Bairéad, poet (1740–1819)

- William James MacNeven, physician and scientist (1763–1841)

- William Higgins, chemist (1763–1825)

- Antoine Ó Raifteiri bard (1784–1835)

- James Hardiman, folklorist and historian (1792–1855)

- Joseph Patrick Haverty, painter (1794–1864)

- James Curley, astronomer and mathematician (1796–1880)

- Colm de Bhailís, songwriter (1796–1906)

- William Cunningham Blest, medical pioneer (1800–1884

- John Birmingham, Astronomer and geologist (1816–1884

- William Larminie, poet and folklorist (1849–1900)

- Augusta, Lady Gregory, dramatist and arts patron (1852–1932)

- George Moore (novelist) (1852–1933)

- Louis Brennan, inventor (1852–1932)

- Percy French, songwriter, (1854–1920)

- William Butler Yeats, poet (1865–1939)

- Violet Florence Martin, novelist and short story writer (1862–1915)

- Grace Rhys, writer (1865–1929)

- Eva Gore-Booth, dramatist (1870–1926)

- Margaret Burke Sheridan, Opera singer (1889–1958)

The Famine to World War One

Connacht was the worst hit area in Ireland during the Great Famine, in particular counties Mayo and Roscommon. In the Census of 1841, the population of Connacht stood at 1,418,859, highest ever recorded. By 1851, the population had fallen to 1,010,031 and would continue to decline until the late 20th century.

In the Annals of Ulster

Historical references to Connacht are generally accepted from the early 6th century onwards, commencing with the battle of Claenloch between the Ui Fiachrach Aidhne and the Ui Maine. It is though that Claenloch is what is now called Coole Lough, four miles north of Gort, in County Galway.

References to the Arts c.1100 to 1700

Literary and historical works were produced in Connacht during these centuries included the Book of Ballymote (c.1391), the Great Book of Lecan (between 1397 and 1418), An Leabhar Breac (c. 1411), Egerton 1782 (early 16th century), and The Book of the Burkes (c.1580). Writers and learned people of the times included:

- Aindileas Ua Chlúmháin, poet, died 1170

- Muireadhach Albanach, Crusader, fl. 1213–1228

- Flann Óge Ó Domhnalláin, ollamh of Connacht, died 1342

- Aed mac Conchbair Mac Aodhagáin, bard, 1330–1359

- Seán Mór Ó Dubhagáin, historian, died 1372

- Murchadh Ó Cuindlis, scribe, fl. 1398–1411

- Giolla Íosa Mór Mac Fhirbhisigh, historian, fl. 1390–1418

- Tadhg Dall Ó hUiginn, poet, murdered 1591

- Baothghalach Mór Mac Aodhagáin, poet, 1550–1600

- Nehemiah Donnellan Archbishop of Tuam, translated New Testament into Irish, died 1609

- Flaithri Ó Maolconaire, theologian, 1560-18 November 1629

- Peregrine Ó Duibhgeannain, scribe of the Annals of the Four Masters, fl. 1627–1636

- Patrick D'Arcy, author of the constitution of Confederate Ireland, 1598–1668

- Mary Bonaventure Browne, religious writer and historian, born after 1610

- Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh, compiler of Leabhar na nGenealach, fl. 1643–1671

- Daibhidh Ó Duibhgheannáin, scribe, compiler, poet, died 1696

- Thomas Connellan, composer, c. 1640/1645–1698

See also

- Galway city

- Connacht Senior Football Championship

- Grace O'Malley

- Kings of Umaill

- Kings of Ui Fiachrach Muaidhe

- Kings of Ui Maine

- Kings of Luighne Connacht

- Kings of Sliabh Lugha

- Corca Fhir Trí

- List of Cities and Towns in Connacht by population

- Coin of Connaught

- The Connaught Rangers

- Duke of Connaught

- Kings of Connacht

- Lords of Connaught

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 ISO 3166-2 Newsletter II-1, 19 February 2010, which gives "Connaught" as the official English name of the Province and "Connacht" as the official Irish name of the Province and cites "Ordnance Survey Office, Dublin 1993" as its source – http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_3166-2_newsletter_ii-1_corrected_2010-02-19.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Province Connacht". Central Statistics Office. 2011.

- ↑ Challoner, Richard. A Memorial of Ancient British Piety: or, a British Martyrology, p. 127. W. Needham, 1761. Accessed 14 March 2013.

- ↑ John Wells

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/documents/census2011vol1andprofile1/Census%202011%20-%20Population%20Classified%20by%20Area.pdf

- ↑ O'Rahilly, T. F. (1942). "Notes, Mainly Etymological". Ériu (Royal Irish Academy) 13: 157.

- ↑ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Pearson Longman. s.v. Connacht; Connaught. ISBN 9781405881173.

- ↑ "Population of Saorstát Éireann and of each Province at each Census since 1881 and the Numbers of Marriages, Births and Deaths Registered in each Intercensal Period since 1871" (PDF). Census 1926 Volume 1 - Population, Area and Valuation of each DED and each larger Unit of Area. CSO. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ "European Assembly Elections Act, 1977, Schedule 2". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ "European Parliament Elections Act, 1993, Section 9". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ "European Parliament Elections Act, 1997, Schedule 3". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ "S.I. No. 91/2014 - Statistics (Carriage of Passengers, Freight and Mail by Air) Order 2013.". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ "S.I. No. 200/1987 - Garda Síochána (Associations) (Superintendents and Chief Superintendents) Regulations, 1987.". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ↑ Beiner, Guy, Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory, University of Wisconsin Press (2007) ISBN 0-299-21824-4 p. 6

- ↑ "County Mayo: An Outline History; Part 3 – 1600 to 1800". Mayo Ireland.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Connacht. |

- http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~irlkik/ihm/connacht.htm#mua

- Census 2011 – Galway Gaeltacht stats

- Census 2011 – Mayo Gaeltacht stats

- Gaeltacht Comprehensive Language Study 2007

- Gaelscoil stats

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||