Concubinage

| Relationships |

|---|

|

Types |

|

Activities |

|

Endings |

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship in which a person engages in an ongoing sexual relationship with another person to whom they are not or cannot be married. The inability to marry may be due to a multiplicity of factors, such as differences in social rank status, an extant marriage, religious prohibitions, professional ones (for example Roman soldiers) or a lack of recognition by appropriate authorities. The woman in such a relationship is referred to as a concubine. Historically, concubinage was frequently voluntary by the woman or her family, as it provided a measure of economic security for the woman involved.

While long-term sexual relationships instead of marriage have become increasingly common in the Western world over the last few decades, these are generally not termed concubinage.

Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece, the practice of keeping a slave concubine (Greek pallakis) was little recorded but appears throughout Athenian history. The law prescribed that a man could kill another man caught attempting a relationship with his concubine for the production of free children, which suggests that a concubine's children were not granted citizenship.[1] While references to the sexual exploitation of maidservants appear in literature, it was considered disgraceful for a man to keep such women under the same roof as his wife.[2] Some interpretations of hetaera have held they were concubines when one had a permanent relationship with a single man.[3]

Ancient Roman concubinae and concubini

Concubinage was an institution practiced in ancient Rome that allowed a man to enter into an informal but recognized relationship with a woman (concubina, plural concubinae) who was not his wife, most often a woman whose lower social status was an obstacle to marriage. Concubinage was "tolerated to the degree that it did not threaten the religious and legal integrity of the family".[4] It was not considered derogatory to be called a concubina, as the title was often inscribed on tombstones.[5]

A concubinus was a young male slave sexually exploited by his master as a sexual partner. See homosexuality in ancient Rome. The sexual abuse of a slave boy by an adult abuser was permitted. These relations, however, were expected to play a secondary role to marriage, within which institution an adult male demonstrated his masculine authority as head of the household (paterfamilias). In one of his epithalamiums, Catullus (fl. mid-1st century BC) assumes that the young bridegroom has a concubinus who considers himself elevated above the other slaves, but who will be set aside as his master turns his attention to marriage and family life.[6]

In the Bible

Among the Israelites, men commonly acknowledged their concubines, and such women enjoyed the same rights in the house as legitimate wives.[7]

The concubine may not have commanded the same respect and inviolability as the wife. In the Levitical rules on sexual relations, the Hebrew word that is commonly translated as "wife" is distinct from the Hebrew word that means "concubine". However, on at least one other occasion the term is used to refer to a woman who is not a wife - specifically, the handmaiden of Jacob's wife.[8] In the Levitical code, sexual intercourse between a man and a wife of a different man was forbidden and punishable by death for both persons involved.[9][10] Since it was regarded as the highest blessing to have many children, wives often gave their maids to their husbands if they were barren, as in the cases of Sarah and Hagar, and Rachel and Bilhah. The children of the concubine often had equal rights with those of the wife;[7] for example, King Abimelech was the son of Gideon and his concubine.[11] Later biblical figures such as Gideon, and Solomon had concubines in addition to many childbearing wives. For example, the Books of Kings say that Solomon had 700 wives and 300 concubines.[12]

The account of the unnamed Levite [13][14] shows that the taking of concubines was not the exclusive preserve of Kings or patriarchs in Israel during the time of the Judges and that the rape of a concubine was completely unacceptable to the Israelite nation and led to a civil war. In the story, the Levite appears to be an ordinary member of the tribe dedicated to the worship of God, who was undoubtedly dishonoured both by the unfaithfulness of his concubine and her abandonment of him. However, after four months, he decides to follow her back to her family home to persuade her to return to him. Her father seeks to delay his return and he does not leave early enough to make the return journey in a single day. The hospitality he is offered at Gibeah, the way in which his host's daughter is offered to the townsmen and the circumstances of his concubine's death at their hands describe a lawless time where visitors are both welcomed and threatened in equal measure. The most disturbing aspect of this account is that both the Levite and his (male) host seek to protect themselves by offering their womenfolk to their aggressors for sex, in exchange for their own safety. The Levite acts in a way that indicates that he believes that the multiple rape of his unfaithful concubine is preferable to the violation of the virginity of his host's daughter or a sexual assault on his own person. In the morning, the Levite appears to be quite indifferent to the condition of his concubine and expects her to resume the journey but she is dead. He dismembers her body and distributes her (body parts) throughout the nation of Israel as a terrible message. This outrages and revolts the Israelite tribesmen who then wreak total retribution on the men of Gibeah and the surrounding tribe of Benjamin when they support them, killing them without mercy and burning all their towns. The inhabitants of (the town of) Jabesh Gilead are then slaughtered as a punishment for not joining the eleven tribes in their war against the Benjamites and their four hundred unmarried daughters given in forced marriage to the six hundred Benjamite survivors. Finally, the two hundred Benjamite survivors who still have no wives are granted a mass marriage by abduction by the other tribes.

There are no concubines in the New Testament. Paul, the apostle, emphasises that church leaders should be in monogamous marriages,[15][16] that believers should not have sexual relationships outside marriage.[17] and that unmarried believers should be celibate.[18] Marriage is to reflect the exclusive relationship between the husband (Christ) and wife (his church),[19] described as a "mystery".

In Judaism

In Judaism, concubines are referred to by the Hebrew term pillegesh. The term is a non-Hebrew, non-Semitic loanword derived from the Greek word, pallakis, Greek παλλακίς,[20][21][22] meaning "a mistress staying in house".

According to the Babylonian Talmud,[7] the difference between a concubine and a full wife was that the latter received a marriage contract (Hebrew: ketubbah) and her marriage (nissu'in) was preceded by a formal betrothal (erusin). Neither was the case for a concubine. One opinion in the Jerusalem Talmud argues that the concubine should also receive a marriage contract, but without a clause specifying a divorce settlement.[7]

Certain Jewish thinkers, such as Maimonides, believed that concubines were strictly reserved for kings, and thus that a commoner may not have a concubine. Indeed, such thinkers argued that commoners may not engage in any type of sexual relations outside of a marriage.

Maimonides was not the first Jewish thinker to criticise concubinage. For example, Leviticus Rabbah severely condemns the custom.[23] Other Jewish thinkers, such as Nahmanides, Samuel ben Uri Shraga Phoebus, and Jacob Emden, strongly objected to the idea that concubines should be forbidden.

In the Hebrew of the contemporary State of Israel, the word pillegesh is often used as the equivalent of the English word mistress—i.e., the female partner in extramarital relations—regardless of legal recognition. Attempts have been initiated to popularise pillegesh as a form of premarital, non-marital or extramarital relationship (which, according to the perspective of the enacting person(s), is permitted by Jewish law).[24][25][26]

In China

In China, successful men often had concubines until the practice was outlawed after the Communist Party of China came to power in 1949. For example, it has been documented that Chinese Emperors accommodated thousands of concubines.[27] A concubine's treatment and situation were highly variable and were influenced by the social status of the male to whom she was engaged, as well as the attitude of the wife. The position of the concubine was generally inferior to that of the wife. Although a concubine could produce heirs, her children would be inferior in social status to "legitimate" children. Allegedly, concubines were occasionally buried alive with their masters to "keep them company in the afterlife".[27]

Despite the limitations imposed on Chinese concubines, history and literature offer examples of concubines who achieved great power and influence. For example, in one of the Four Great Classical Novels of China, The Dream of the Red Chamber (believed to be a semi-autobiographical account of author Cao Xueqin's own family life), three generations of the Jia family are supported by one favorite concubine of the Emperor.

Imperial concubines, kept by Emperors in the Forbidden City, were traditionally guarded by eunuchs to ensure that they could not be impregnated by anyone but the Emperor.[27] Lady Yehenara, otherwise known as Dowager Empress Cixi, was arguably one of the most successful concubines in China's history. Cixi first entered the court as a concubine to the Xianfeng Emperor and gave birth to his only surviving son, who would become the Tongzhi Emperor. She would eventually become the de facto ruler of the Manchu Qing Dynasty in China for 47 years after her husband's death.[28]

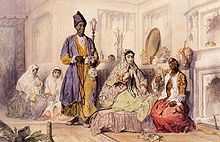

In Islam

Chapter four (Surat-un-Nisa), verse three of the Quran [29] states that a man may be married to a maximum of four women if he can treat them with justice, and if he is unable to be just among plural wives, he may marry only one woman.

Islam considers every human free from birth (Deen-al-Fitrah).[30] Concubines were common in pre-Islamic era and when Islam arrived, it had a society with concubines. Islam never encouraged concubines but accepted pre-existing concubines as social members and encouraged gradual elimination of this practice through manumission and marriages. Children of concubines were declared legitimate as children born in wedlock, and the mother of a free child was considered free upon the death of the male partner. A concubine was expected to maintain her chastity in the same manner as a free woman; however, the penalty to be exacted by the Shari'a for a convicted transgression was half that of a free woman. The expectation of a wife to adorn herself and be attentive to the man's desires, which is a formal part of Islamic adab (religiously prescribed comportment) did not extend to concubines.

Ancient times

In ancient times, Islam imposed very strict checks on how a woman became a concubine in order to prevent misuse. In ancient times, two sources for concubines were permitted under an Islamic regime. Primarily, non-Muslim women taken as prisoners of war were made concubines as happened after the Battle of Bani Qariza.[31] Alternately, in ancient (Pagan/Pre-Islamic) times, sale and purchase of human slaves was a socially legal exercise. However, Islam encouraged their manumission in general. On embracing Islam, it was encouraged to manumit slave women or bring them into formal marriage (Nikah).

Modern times

According to the rules of Islamic Fiqh, what is halal (permitted) by Allah in the Quran cannot be altered by any authority or individual. Therefore, although the concept of concubinage is halal, concubines are mostly no longer available in this modern era nor allowed to be sold or purchased in accordance with the latest human rights standards. However, as change of existing Islamic law is impossible, a concubine in this modern era must be given all the due rights that Islam had preserved in the past.

It is further clarified that all domestic and organizational female employees are not concubines in this era and hence sex is forbidden with them unless Nikah (formal marriage) [32] or mut'ah[33] (temporary marriage - which only Shi'ah Islam permits) is committed through the proper channels. The Sunni scholars also do not allow mut'ah, or temporary marriage. Although sometimes the two are confused, Mut'ah is not concubinage.

In the United States

When slavery became institutionalized in the North American colonies, white men, whether or not they were married, sometimes took enslaved women as concubines, most often against the will of the woman. Marriage between the races was prohibited by law in the colonies and the later United States. Many colonies and states also had laws against miscegenation, or any interracial relations. From 1662 the Colony of Virginia, followed by others, incorporated into law the principle that children took their mother's status, i.e., the principle of partus sequitur ventrem. All children born to enslaved mothers were born into slavery, regardless of their father's status or ancestry.[34] This led to generations of mixed-race slaves, some of whom were otherwise considered legally white (one-eighth or less African, equivalent to a great-grandparent) before the American Civil War.

In some cases, men had long-term relationships with enslaved women, giving them and their mixed-race children freedom and providing their children with apprenticeships, education and transfer of capital. In other cases, the men did nothing for the women except in a minor way. Such arrangements were more prevalent in the South during the antebellum years.

Historians widely believe that the widower Thomas Jefferson, both before and during his presidency of the United States in the early 19th century, had an intimate relationship of 38 years with his mixed-race slave Sally Hemings and fathered all of her six children of record.[35] He freed all four of her surviving children as they came of age. The Hemingses were the only slave family to go free from Monticello. The children were seven-eighths European in ancestry and legally white. Three entered the white community as adults. A 1998 DNA study showed a match between the Jefferson male line and a male descendant of Sally Hemings.[35]

In Louisiana and former French territories, a formalized system of concubinage called plaçage developed. European men took enslaved or free women of color as mistresses after making arrangements to give them a dowry, house or other transfer of property, and sometimes, if they were enslaved, offering freedom and education for their children.[36] A third class of free people of color developed, especially in New Orleans.[36][37] Many became educated, artisans and property owners. French-speaking and practicing Catholics, who combined French and African-American culture, created an elite between the whites of European descent and the masses of slaves.[36] Today descendants of the free people of color are generally called Louisiana Creole people.[36]

See also

- Cicisbeo

- Cohabitation

- Common-law marriage

- Courtesan

- Cullagium

- Free Union

- Harem

- Ma malakat aymanukum

- Monogamy

- Monogamy in Christianity

- Morganatic marriage

- Mistress (lover)

- Paramour

- Pilegesh

- Polygamy

- Polyamory

- Polygyny

- Romeo and Juliet

- Slavery in the United States

References

- ↑ James Davidson. Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. p. 98. ISBN 0-312-18559-6.

- ↑ James Davidson. Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-312-18559-6.

- ↑ James Davidson. Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. p. 101. ISBN 0-312-18559-6.

- ↑ Grimal, Love in Ancient Rome (University of Oklahoma Press) 1986:111.

- ↑ Kiefer, Sexual Life in Ancient Rome (Kegan Paul International) 2000:50.

- ↑ Catullus, Carmen 61; Amy Richlin, "Not before Homosexuality: The Materiality of the cinaedus and the Roman Law against Love between Men", Journal of the History of Sexuality 3.4 (1993), pp. 534–535.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Staff (2002–2011). "PILEGESH (Hebrew, ; comp. Greek, παλλακίς).". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ Genesis 30:4

- ↑ Leviticus 20:10

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:22

- ↑ Judges 8:31

- ↑ 1 Kings 11:1-3

- ↑ Judges 19

- ↑ Judges 20

- ↑ Timothy&verse=3:2&src= 1 Timothy 3:2

- ↑ Timothy&verse=3:12&src= 1 Timothy 3:12

- ↑ Corinthians&verse=3:1-2&src= 1 Corinthians 3:1-2

- ↑ Corinthians&verse=3:8-9&src= 1 Corinthians 3:8-9

- ↑ Ephesians 5:31-32

- ↑ Michael Lieb, Milton and the culture of violence, p.274, Cornell University Press, 1994

- ↑ Agendas for the study of Midrash in the twenty-first century, Marc Lee Raphael, p.136, Dept. of Religion, College of William and Mary, 1999

- ↑ Nicholas Clapp, Sheba: Through the Desert in Search of the Legendary Queen, p.297, Houghton Mifflin, 2002

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah, 25

- ↑ Matthew Wagner (16 March 2006). "Kosher sex without marriage". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ Adam Dickter, "ISO: Kosher Concubine", New York Jewish Week, December 2006

- ↑ Suzanne Glass, "The Concubine Connection", The Independent, London 20 October 1996

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "Concubines of Ancient China". Beijing Made Easy. Beijing Made Easy. 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ Sterling Seagrave, Peggy Seagrave (1993). Dragon lady: the life and legend of the last empress of China. Vintage Books.

- ↑ Al-Quran Chapter 4, Verse 3

- ↑ Al-Quran, Chapter 5

- ↑ Majlisi, M. B. (1966). Hayat-ul-Qaloob, Volume 2, Translated by Molvi Syed Basharat Hussain Sahib Kamil, Imamia Kutub Khana, Lahore, Pakistan

- ↑ Nikah.com Information: Definitiion of Nikah (Islamic marriage)

- ↑ Motahhari M. "The rights of woman in Islam, fixed-term marriage and the problem of the harem". Al-islam.org website. Accessed 15 March 2014.

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 17

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account", Monticello Website, Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved 22 June 2011. Quote: "Ten years later [referring to its 2000 report], TJF and most historians now believe that, years after his wife's death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston Hemings."

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Helen Bush Caver and Mary T. Williams, "Creoles", Multicultural America, Countries and Their Cultures Website. Retrieved 3 Feb 2009

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619–1865, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, pp. 82-83

External links

| Look up concubine in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Servile Concubinage

Works related to Concubinage at Wikisource

Works related to Concubinage at Wikisource