Computer font

A computer font (or font) is an electronic data file containing a set of glyphs, characters, or symbols such as dingbats. Although the term font first referred to a set of metal type sorts in one style and size, since the 1990s it is generally used to refer to a scalable set of digital shapes that may be printed at many different sizes.

There are three basic kinds of computer font file data formats:

- Bitmap fonts consist of a matrix of dots or pixels representing the image of each glyph in each face and size.

- Outline fonts (also called vector fonts) use Bézier curves, drawing instructions and mathematical formulae to describe each glyph, which make the character outlines scalable to any size.

- Stroke fonts use a series of specified lines and additional information to define the profile, or size and shape of the line in a specific face, which together describe the appearance of the glyph.

Bitmap fonts are faster and easier to use in computer code, but non-scalable, requiring a separate font for each size. Outline and stroke fonts can be resized using a single font and substituting different measurements for components of each glyph, but are somewhat more complicated to render on screen than bitmap fonts, as they require additional computer code to render the outline to a bitmap for display on screen or in print. Although all types are still in use, most fonts seen and used on computers are outline fonts.

A raster image can be displayed in a different size only with some distortion, but renders quickly; outline or stroke image formats are resizable but take more time to render as pixels must be drawn from scratch each time they are displayed.

Fonts are designed and created using font editors. Fonts specifically designed for the computer screen and not printing are known as screen fonts.

Fonts can be monospaced (i.e., every character is plotted a constant distance from the previous character that it is next to, while drawing) or proportional (each character has its own width). However, the particular font-handling application can affect the spacing, particularly when doing justification.

Font types

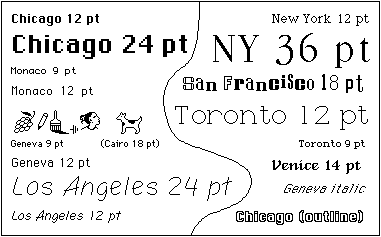

Bitmap fonts

A bitmap font is one that stores each glyph as an array of pixels (that is, a bitmap). It is less commonly known as a raster font. Bitmap fonts are simply collections of raster images of glyphs. For each variant of the font, there is a complete set of glyph images, with each set containing an image for each character. For example, if a font has three sizes, and any combination of bold and italic, then there must be 12 complete sets of images.

Advantages of bitmap fonts include:

- Extremely fast and simple to render

- Unscaled bitmap fonts always give exactly the same output

- Easier to create than other kinds.

The primary disadvantage of bitmap fonts is that the visual quality tends to be poor when scaled or otherwise transformed, compared to outline and stroke fonts, and providing many optimized and purpose-made sizes of the same font dramatically increases memory usage. The earliest bitmap fonts were only available in certain optimized sizes such as 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 18, 24, 36, 48, 72, and 96 points, with custom fonts often available in only one specific size, such as a headline font at only 72 points.

The limited processing power and memory of early computer systems forced exclusive use of bitmap fonts. Improvements in hardware have allowed them to be replaced with outline or stroke fonts in cases where arbitrary scaling is desirable, but bitmap fonts are still in common use in embedded systems and other places where speed and simplicity are considered important.

Bitmap fonts are used in the Linux console, the Windows recovery console, and embedded systems. Older dot matrix printers used bitmap fonts; often stored in the memory of the printer and addressed by the computer's print driver. Bitmap fonts may be used in cross-stitch.

To draw a string using a bitmap font, means to successively output bitmaps of each character that the string comprises, performing per-character indentation.

Monochrome fonts vs. fonts with shades of gray

Digital bitmap fonts (and the final rendering of vector fonts) may use monochrome or shades of gray. The latter is anti-aliased. When displaying a text, typically an operating system properly represents the "shades of gray" as intermediate colors between the color of the font and that of the background. However, if the text is represented as an image with transparent background, "shades of gray" require an image format allowing partial transparency.

Scaling

Bitmap fonts look best at their native pixel size. Some systems using bitmap fonts can create some font variants algorithmically. For example, the original Apple Macintosh computer could produce bold by widening vertical strokes and oblique by shearing the image. At non-native sizes, many text rendering systems perform nearest-neighbor resampling, introducing rough jagged edges. More advanced systems perform anti-aliasing on bitmap fonts whose size does not match the size that the application requests. This technique works well for making the font smaller but not as well for increasing the size, as it tends to blur the edges. Some graphics systems that use bitmap fonts, especially those of emulators, apply curve-sensitive nonlinear resampling algorithms such as 2xSaI or hq3x on fonts and other bitmaps, which avoids blurring the font while introducing little objectionable distortion at moderate increases in size.

The difference between bitmap fonts and outline fonts is similar to the difference between bitmap and vector image file formats. Bitmap fonts are like image formats such as Windows Bitmap (.bmp), Portable Network Graphics (.png) and Tagged Image Format (.tif or .tiff), which store the image data as a grid of pixels, in some cases with compression. Outline or stroke image formats such as Windows Metafile format (.wmf) and Scalable Vector Graphics format (.svg), store instructions in the form of lines and curves of how to draw the image rather than storing the image itself.

A "trace" program can follow the outline of a high-resolution bitmap font and create an initial outline that a font designer uses to create an outline font useful in systems such as PostScript or TrueType. Outline fonts scale easily without jagged edges or blurriness.

Bitmap font formats

- Portable Compiled Format (PCF)

- Glyph Bitmap Distribution Format (BDF)

- Server Normal Format (SNF)

- DECWindows Font (DWF)

- Sun X11/NeWS format (BF, AFM)

- Microsoft Windows bitmapped font (FON)

- Amiga Font, ColorFont, AnimFont

- ByteMap Font (BMF)

- PC Screen Font (PSF)

- Packed bitmap font bitmap file for TeX DVI drivers (PK)

Outline fonts

Outline fonts or vector fonts are collections of vector images, consisting of lines and curves defining the boundary of glyphs. Early vector fonts were used by vector monitors and vector plotters using their own internal fonts, usually with thin single strokes instead of thick outlined glyphs. The advent of desktop publishing brought the need for a universal standard to integrate the graphical user interface of the first Macintosh and laser printers. The term to describe the integration technology was WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get). The universal standard was (and still is) Adobe PostScript. Examples are PostScript Type 1 and Type 3 fonts, TrueType and OpenType.

The primary advantage of outline fonts is that, unlike bitmap fonts, they are a set of lines and curves instead of pixels; they can be scaled without causing pixellation. Therefore, outline font characters can be scaled to any size and otherwise transformed with more attractive results than bitmap fonts, but require considerably more processing and may yield undesirable rendering, depending on the font, rendering software, and output size. Even so, outline fonts can be transformed into bitmap fonts beforehand if necessary. The converse transformation is considerably harder, since bitmap fonts requires heuristic algorithm to guess and approximate the corresponding curves if the pixels do not make a straight line.

Outline fonts have a major problem, in that Bézier curves cannot be rendered accurately onto a raster display (such as most computer monitors and printers), and their rendering can change shape depending on the desired size and position.[1] Measures such as font hinting have to be used to reduce the visual impact of this problem, which require sophisticated software that is difficult to implement correctly. Many modern desktop computer systems include software to do this, but they use considerably more processing power than bitmap fonts, and there can be minor rendering defects, particularly at small font sizes. Despite this, they are frequently used because people often consider the processing time and defects to be acceptable when compared to the ability to scale fonts freely.

Outline font formats

Type 1 and Type 3 fonts

Type 1 and Type 3 fonts were developed by Adobe for professional digital typesetting. Using PostScript, the glyphs are outline fonts described with cubic Bezier curves. Type 1 fonts were restricted to a subset of the PostScript language, and used Adobe's hinting system, which used to be very expensive. Type 3 allowed unrestricted use of the PostScript language, but didn't include any hint information, which could lead to visible rendering artifacts on low-resolution devices (such as computer screens and dot-matrix printers).

TrueType fonts

TrueType is a font system originally developed by Apple Inc. It was intended to replace Type 1 fonts, which many felt were too expensive. Unlike Type 1 fonts, TrueType glyphs are described with quadratic Bezier curves. It is currently very popular and implementations exist for all major operating systems.

OpenType fonts

OpenType is a smartfont system designed by Adobe and Microsoft. OpenType fonts contain outlines in either the TrueType or Type 1 (actually CFF) format together with a wide range of metadata.

Stroke-based fonts

A glyph's outline is defined by the vertices of individual stroke paths, and the corresponding stroke profiles. The stroke paths are a kind of topological skeleton of the glyph. The advantages of stroke-based fonts over outline fonts include reducing number of vertices needed to define a glyph, allowing the same vertices to be used to generate a font with a different weight, glyph width, or serifs using different stroke rules, and the associated size savings. For a font developer, editing a glyph by stroke is easier and less prone to error than editing outlines. A stroke-based system also allows scaling glyphs in height or width without altering stroke thickness of the base glyphs. Stroke-based fonts are heavily marketed for East Asian markets for use on embedded devices, but the technology is not limited to ideograms.

Commercial developers included Agfa Monotype (iType), Type Solutions, Inc. (owned by Bitstream Inc.) (Font Fusion (FFS), btX2), Fontworks (Gaiji Master), which have independently developed stroke-based font types and font engines.

Although Monotype and Bitstream have claimed tremendous space saving using stroke-based fonts on East Asian character sets, most of the space saving comes from building composite glyphs, which is part of the TrueType specification and does not require a stroke-based approach.

Stroke-based font formats

METAFONT uses a different sort of glyph description. Like TrueType, it is a vector font description system. It draws glyphs using strokes produced by moving a polygonal or elliptical pen approximated by a polygon along a path made from cubic composite Bézier curves and straight line segments, or by filling such paths. Although when stroking a path the envelope of the stroke is never actually generated, the method causes no loss of accuracy or resolution. The method Metafont uses is more mathematically complex because the parallel curves of a Bézier can be 10th order algebraic curves.[2]

In 2004, DynaComware developed DigiType, a stroke-based font format. In 2006, the creators of the Saffron Type System announced a representation for stroke-based fonts called Stylized Stroke Fonts (SSFs) whith the aim of providing the expressiveness of traditional outline-based fonts and the small memory footprint of uniform-width stroke-based fonts (USFs).[3]

See also

- Adobe Systems, Inc. v. Southern Software, Inc., a United States district court case regarding copyright protection for computer fonts

- Apple Advanced Typography

- Kerning

- List of fonts

- Font hinting

- Fontlab

- OpenType

- Smartfont

- Typeface

- Typesetting

- Intellectual property protection of typefaces

- TeX, LaTeX, and MetaPost

- Saffron Type System, a high-quality anti-aliased text-rendering engine

- Unicode typefaces

- Web typography, explains methods of font embedding into websites

References

- ↑ Stamm, Beat (1998-03-25). "The raster tragedy at low resolution".

- ↑ Mark Kilgard (10 April 2012). "Vector Graphics & Path Rendering". p. 28.

- ↑ Jakubiak, Elena J.; Perry, Ronald N.; Frisken, Sarah F. An Improved Representation for Stroke-based Fonts. SIGGRAPH 2006.

External links

- Finding Fonts FAQ (Microsoft)

- Font Technologies chapter of the LDP's Font-HOWTO

- Microsoft's font guide

- Font Browser

- Glossary of Font Terms Over 50 entries with helpful diagram

- History and technology of computer fonts, Annals of the History of Computing, IEEE, Apr-Jun 1998, Vol. 20, Issue 2, pages 30-34, ISSN 1058-6180

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||