Composition (combinatorics)

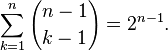

In mathematics, a composition of an integer n is a way of writing n as the sum of a sequence of (strictly) positive integers. Two sequences that differ in the order of their terms define different compositions of their sum, while they are considered to define the same partition of that number. Every integer has finitely many distinct compositions. Negative numbers do not have any compositions, but 0 has one composition, the empty sequence. Each positive integer n has 2n−1 distinct compositions.

A weak composition of an integer n is similar to a composition of n, but allowing terms of the sequence to be zero: it is a way of writing n as the sum of a sequence of non-negative integers. As a consequence every positive integer admits infinitely many weak compositions (if their length is not bounded). Adding a number of terms 0 to the end of a weak composition is usually not considered to define a different weak composition; in other words, weak compositions are assumed to be implicitly extended indefinitely by terms 0.

To further generalize, an A-restricted composition of an integer n, for a subset A of the (nonnegative or positive) integers, is an ordered collection of one or more elements in A whose sum is n.[1]

Examples

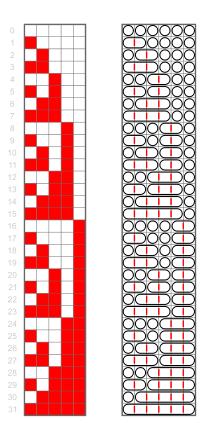

1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1

2 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1

1 + 2 + 1 + 1 + 1

. . .

1 + 5

6

1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1

2 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1

3 + 1 + 1 + 1

. . .

3 + 3

6

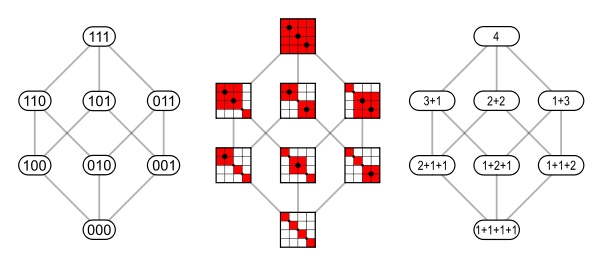

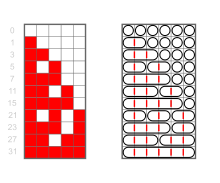

The sixteen compositions of 5 are:

- 5

- 4 + 1

- 3 + 2

- 3 + 1 + 1

- 2 + 3

- 2 + 2 + 1

- 2 + 1 + 2

- 2 + 1 + 1 + 1

- 1 + 4

- 1 + 3 + 1

- 1 + 2 + 2

- 1 + 2 + 1 + 1

- 1 + 1 + 3

- 1 + 1 + 2 + 1

- 1 + 1 + 1 + 2

- 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1.

Compare this with the seven partitions of 5:

- 5

- 4 + 1

- 3 + 2

- 3 + 1 + 1

- 2 + 2 + 1

- 2 + 1 + 1 + 1

- 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1.

It is possible to put constraints on the parts of the compositions. For example the five compositions of 5 into distinct terms are:

- 5

- 4 + 1

- 3 + 2

- 2 + 3

- 1 + 4.

Compare this with the three partitions of 5 into distinct terms:

- 5

- 4 + 1

- 3 + 2.

Number of compositions

Conventionally the empty composition is counted as the sole composition of 0, and there are no compositions of negative integers. There are 2n−1 compositions of n ≥ 1; here is a proof:

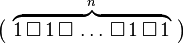

Placing either a plus sign or a comma in each of the n − 1 boxes of the array

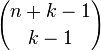

produces a unique composition of n. Conversely, every composition of n determines an assignment of pluses and commas. Since there are n − 1 binary choices, the result follows. The same argument shows that the number of compositions of n into exactly k parts is given by the binomial coefficient  . Note that by summing over all possible number of parts we recover 2n−1 as the total number of compositions of n:

. Note that by summing over all possible number of parts we recover 2n−1 as the total number of compositions of n:

For weak compositions, the number is  , since each k-composition of n + k corresponds to a weak one of n by the rule [a + b + ... + c = n + k] → [(a − 1) + (b − 1) + ... + (c − 1) = n].

, since each k-composition of n + k corresponds to a weak one of n by the rule [a + b + ... + c = n + k] → [(a − 1) + (b − 1) + ... + (c − 1) = n].

For A-restricted compositions, the number of compositions of n into exactly k parts is given by the extended binomial (or polynomial) coefficient ^k](../I/m/4a4c8fabcd7ccf7db341a68300dc6223.png) .[2]

.[2]

See also

Stars and bars (combinatorics)

References

- ↑ Heubach, Silvia; Mansour, Toufik (2004). "Compositions of n with parts in a set". Congressus Numerantium 168: 33–51.

- ↑ Eger, Steffen (2013). "Restricted weighted integer compositions and extended binomial coefficients". Journal of Integer Sequences 16.

- Heubach, Silvia; Mansour, Toufik (2009). Combinatorics of Compositions and Words. Discrete Mathematics and its Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-7267-9. Zbl 1184.68373.