Complexification

In mathematics, the complexification of a real vector space V is a vector space VC over the complex number field obtained by formally extending scalar multiplication to include multiplication by complex numbers. Any basis for V over the real numbers serves as a basis for VC over the complex numbers.

Formal definition

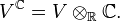

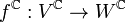

Let V be a real vector space. The complexification of V is defined by taking the tensor product of V with the complex numbers (thought of as a two-dimensional vector space over the reals):

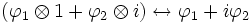

The subscript R on the tensor product indicates that the tensor product is taken over the real numbers (since V is a real vector space this is the only sensible option anyway, so the subscript can safely be omitted). As it stands, VC is only a real vector space. However, we can make VC into a complex vector space by defining complex multiplication as follows:

More generally, complexification is an example of extension of scalars – here extending scalars from the real numbers to the complex numbers – which can be done for any field extension, or indeed for any morphism of rings.

Formally, complexification is a functor VectR → VectC, from the category of real vector spaces to the category of complex vector spaces. This is the adjoint functor – specifically the left adjoint – to the forgetful functor VectC → VectR from forgetting the complex structure.

Basic properties

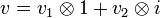

By the nature of the tensor product, every vector v in VC can be written uniquely in the form

where v1 and v2 are vectors in V. It is a common practice to drop the tensor product symbol and just write

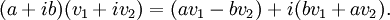

Multiplication by the complex number a + ib is then given by the usual rule

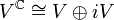

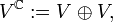

We can then regard VC as the direct sum of two copies of V:

with the above rule for multiplication by complex numbers.

There is a natural embedding of V into VC given by

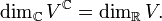

The vector space V may then be regarded as a real subspace of VC. If V has a basis {ei} (over the field R) then a corresponding basis for VC is given by {ei ⊗ 1} over the field C. The complex dimension of VC is therefore equal to the real dimension of V:

Alternatively, rather than using tensor products, one can use this direct sum as the definition of the complexification:

where  is given a linear complex structure by the operator J defined as

is given a linear complex structure by the operator J defined as  where J encodes the data of "multiplication by i". In matrix form, J is given by:

where J encodes the data of "multiplication by i". In matrix form, J is given by:

This yields the identical space – a real vector space with linear complex structure is identical data to a complex vector space – though it constructs the space differently. Accordingly,  can be written as

can be written as  or

or  identifying V with the first direct summand. This approach is more concrete, and has the advantage of avoiding the use of the technically involved tensor product, but is ad hoc.

identifying V with the first direct summand. This approach is more concrete, and has the advantage of avoiding the use of the technically involved tensor product, but is ad hoc.

Examples

- The complexification of real coordinate space Rn is complex coordinate space Cn.

- Likewise, if V consists of the m×n matrices with real entries, VC would consist of m×n matrices with complex entries.

- The complexification of quaternions is the biquaternions.

- The complexification of the split-complex numbers is the tessarines.

Complex conjugation

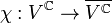

The complexified vector space VC has more structure than an ordinary complex vector space. It comes with a canonical complex conjugation map:

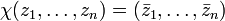

defined by

The map χ may either be regarded as a conjugate-linear map from VC to itself or as a complex linear isomorphism from VC to its complex conjugate  .

.

Conversely, given a complex vector space W with a complex conjugation χ, W is isomorphic as a complex vector space to the complexification VC of the real subspace

In other words, all complex vector spaces with complex conjugation are the complexification of a real vector space.

For example, when W = Cn with the standard complex conjugation

the invariant subspace V is just the real subspace Rn.

Linear transformations

Given a real linear transformation f : V → W between two real vector spaces there is a natural complex linear transformation

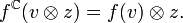

given by

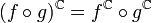

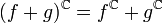

The map fC is naturally called the complexification of f. The complexification of linear transformations satisfies the following properties

In the language of category theory one says that complexification defines an (additive) functor from the category of real vector spaces to the category of complex vector spaces.

The map fC commutes with conjugation and so maps the real subspace of VC to the real subspace of WC (via the map f). Moreover, a complex linear map g : VC → WC is the complexification of a real linear map if and only if it commutes with conjugation.

As an example consider a linear transformation from Rn to Rm thought of as an m × n matrix. The complexification of that transformation is exactly the same matrix, but now thought of as a linear map from Cn to Cm.

Dual spaces and tensor products

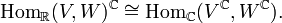

The dual of a real vector space V is the space V* of all real linear maps from V to R. The complexification of V* can naturally be thought of as the space of all real linear maps from V to C (denoted HomR(V,C)). That is,

The isomorphism is given by

where φ1 and φ2 are elements of V*. Complex conjugation is then given by the usual operation

Given a real linear map φ : V → C we may extend by linearity to obtain a complex linear map φ : VC → C. That is,

This extension gives an isomorphism from HomR(V,C)) to HomC(VC,C). The latter is just the complex dual space to VC, so we have a natural isomorphism:

More generally, given real vector spaces V and W there is a natural isomorphism

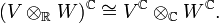

Complexification also commutes with the operations of taking tensor products, exterior powers and symmetric powers. For example, if V and W are real vector spaces there is a natural isomorphism

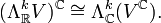

Note the left-hand tensor product is taken over the reals while the right-hand one is taken over the complexes. The same pattern is true in general. For instance, one has

In all cases, the isomorphisms are the “obvious” ones.

See also

- Extension of scalars – general process

- Linear complex structure

References

- Paul Halmos (1958, 1974) Finite-Dimensional Vector Spaces, p 41 and §77 Complexification, pp 150–153, Springer, ISBN 0-387-90093-4 .

- Ronald Shaw (1982) Linear Algebra and Group Representations, v. 1, §1.5.4 Complexification and realification, pp 40–2 & §5.5.2 Complexification p 196, Academic Press ISBN 0-12-639201-3 .

- Roman, Steven (2005). Advanced Linear Algebra. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 135 ((2nd ed.) ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-24766-1.