Combinatorial proof

In mathematics, the term combinatorial proof is often used to mean either of two types of mathematical proof:

- A proof by double counting. A combinatorial identity is proven by counting the number of elements of some carefully chosen set in two different ways to obtain the different expressions in the identity. Since those expressions count the same objects, they must be equal to each other and thus the identity is established.

- A bijective proof. Two sets are shown to have the same number of members by exhibiting a bijection, i.e. a one-to-one correspondence, between them.

The term "combinatorial proof" may also be used more broadly to refer to any kind of elementary proof in combinatorics. However, as Glass (2003) writes in his review of Benjamin & Quinn (2003) (a book about combinatorial proofs), these two simple techniques are enough to prove many theorems in combinatorics and number theory.

Example

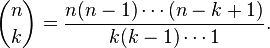

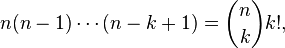

An archetypal double counting proof is for the well known formula for the number  of k-combinations (i.e., subsets of size k) of an n-element set:

of k-combinations (i.e., subsets of size k) of an n-element set:

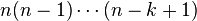

Here a direct bijective proof is not possible: because the right-hand side of the identity is a fraction, there is no set obviously counted by it (it even takes some thought to see that the denominator always evenly divides the numerator). However its numerator counts the Cartesian product of k finite sets of sizes n, n − 1, ..., n − k + 1, while its denominator counts the permutations of a k-element set (the set most obviously counted by the denominator would be another Cartesian product k finite sets; if desired one could map permutations to that set by an explicit bijection). Now take S to be the set of sequences of k elements selected from our n-element set without repetition. On one hand, there is an easy bijection of S with the Cartesian product corresponding to the numerator  , and on the other hand there is a bijection from the set C of pairs of a k-combination and a permutation σ of k to S, by taking the elements of C in increasing order, and then permuting this sequence by σ to obtain an element of S. The two ways of counting give the equation

, and on the other hand there is a bijection from the set C of pairs of a k-combination and a permutation σ of k to S, by taking the elements of C in increasing order, and then permuting this sequence by σ to obtain an element of S. The two ways of counting give the equation

and after division by k! this leads to the stated formula for  . In general, if the counting formula involves a division, a similar double counting argument (if it exists) gives the most straightforward combinatorial proof of the identity, but double counting arguments are not limited to situations where the formula is of this form.

. In general, if the counting formula involves a division, a similar double counting argument (if it exists) gives the most straightforward combinatorial proof of the identity, but double counting arguments are not limited to situations where the formula is of this form.

The benefit of a combinatorial proof

Stanley (1997) gives an example of a combinatorial enumeration problem (counting the number of sequences of k subsets S1, S2, ... Sk, that can be formed from a set of n items such that the subsets have an empty common intersection) with two different proofs for its solution. The first proof, which is not combinatorial, uses mathematical induction and generating functions to find that the number of sequences of this type is (2k −1)n. The second proof is based on the observation that there are 2k −1 proper subsets of the set {1, 2, ..., k}, and (2k −1)n functions from the set {1, 2, ..., n} to the family of proper subsets of {1, 2, ..., k}. The sequences to be counted can be placed in one-to-one correspondence with these functions, where the function formed from a given sequence of subsets maps each element i to the set {j | i ∈ Sj}.

Stanley writes, “Not only is the above combinatorial proof much shorter than our previous proof, but also it makes the reason for the simple answer completely transparent. It is often the case, as occurred here, that the first proof to come to mind turns out to be laborious and inelegant, but that the final answer suggests a simple combinatorial proof.” Due both to their frequent greater elegance than non-combinatorial proofs and the greater insight they provide into the structures they describe, Stanley formulates a general principle that combinatorial proofs are to be preferred over other proofs, and lists as exercises many problems of finding combinatorial proofs for mathematical facts known to be true through other means.

The difference between bijective and double counting proofs

Stanley does not clearly distinguish between bijective and double counting proofs, and gives examples of both kinds, but the difference between the two types of combinatorial proof can be seen in an example provided by Aigner & Ziegler (1998), of proofs for Cayley's formula stating that there are nn − 2 different trees that can be formed from a given set of n nodes. Aigner and Ziegler list four proofs of this theorem, the first of which is bijective and the last of which is a double counting argument. They also mention but do not describe the details of a fifth bijective proof.

The most natural way to find a bijective proof of this formula would be to find a bijection between n-node trees and some collection of objects that has nn − 2 members, such as the sequences of n − 2 values each in the range from 1 to n. Such a bijection can be obtained using the Prüfer sequence of each tree. Any tree can be uniquely encoded into a Prüfer sequence, and any Prüfer sequence can be uniquely decoded into a tree; these two results together provide a bijective proof of Cayley's formula.

An alternative bijective proof, given by Aigner and Ziegler and credited by them to André Joyal, involves a bijection between, on the one hand, n-node trees with two designated nodes (that may be the same as each other), and on the other hand, n-node directed pseudoforests. If there are Tn n-node trees, then there are n2Tn trees with two designated nodes. And a pseudoforest may be determined by specifying, for each of its nodes, the endpoint of the edge extending outwards from that node; there are n possible choices for the endpoint of a single edge (allowing self-loops) and therefore nn possible pseudoforests. By finding a bijection between trees with two labeled nodes and pseudoforests, Joyal's proof shows that Tn = nn − 2.

Finally, the fourth proof of Cayley's formula presented by Aigner and Ziegler is a double counting proof due to Jim Pitman. In this proof, Pitman considers the sequences of directed edges that may be added to an n-node empty graph to form from it a single rooted tree, and counts the number of such sequences in two different ways. By showing how to derive a sequence of this type by choosing a tree, a root for the tree, and an ordering for the edges in the tree, he shows that there are Tnn! possible sequences of this type. And by counting the number of ways in which a partial sequence can be extended by a single edge, he shows that there are nn − 2n! possible sequences. Equating these two different formulas for the size of the same set of edge sequences and cancelling the common factor of n! leads to Cayley's formula.

Related concepts

- The principles of double counting and bijection used in combinatorial proofs can be seen as examples of a larger family of combinatorial principles, which include also other ideas such as the pigeonhole principle.

- Proving an identity combinatorially can be viewed as adding more structure to the identity by replacing numbers by sets; similarly, categorification is the replacement of sets by categories.

References

- Aigner, Martin; Ziegler, Günter M. (1998), Proofs from THE BOOK, Springer-Verlag, pp. 141–146, ISBN 3-540-40460-0.

- Benjamin, Arthur T.; Quinn, Jennifer J. (2003), Proofs that Really Count: The Art of Combinatorial Proof, Dolciani Mathematical Expositions 27, Mathematical Association of America, ISBN 978-0-88385-333-7.

- Glass, Darren (2003), Read This: Proofs that Really Count, Mathematical Association of America.

- Stanley, Richard P. (1997), Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume I, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics 49, Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–12, ISBN 0-521-55309-1.