Coluber constrictor foxii

| Coluber constrictor foxii | |

|---|---|

| |

| blue racer | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Subfamily: | Colubrinae |

| Genus: | Coluber |

| Species: | C. constrictor |

| Subspecies: | C. c. foxii |

| Trinomial name | |

| Coluber constrictor foxii (Baird & Girard, 1853) | |

| Synonyms | |

Coluber constrictor foxii, commonly known as the blue racer, is a subspecies of Coluber constrictor, a species of nonvenomous, colubrid snakes commonly referred to as the eastern racers.

Distribution

Blue racers prefer open and semi-open habitat, savanna, old field shoreline, and edge habitats. It is likely that a mosaic of these habitats is required to fulfill the ecological needs of C. c. foxii.

In the United States: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Oregon, Washington, and Iowa are now the only states with extant populations of blue racer. The last reliable record of the blue racer on mainland Canada was in Ontario in 1983. On Pelee Island in Ontario, the blue racer is restricted to the eastern two thirds of the island.

Description

Blue racers often have creamy white ventral scales, dull grey to brilliant blue lateral scales, and pale brown to dark grey dorsums. They also have characteristic black masks, relatively large eyes, and often have brownish-orange rostral scales (snouts). Unlike adults, hatchlings and yearlings (first full active season) have dorsal blotches that fade completely by the third year; however, juvenile patterning is still visible on the venter until late in the snake's third season.

The blue racer is one of Ontario's largest snakes, reaching 90 cm to 152 cm snout-to-vent length (SVL). The largest documented specimen captured on Pelee Island was 138 cm SVL. Although there has been some controversy regarding the designation of C.c. foxii as a subspecies distinct from C.c. flaviventris (the yellow-bellied racers), most recent authorities agree that the subspecies C.c. foxii is valid.[1]

Behavior/Adaptability

Blue racers seem to be relatively intolerant of high levels of human activity and for most of the active season they remain in areas of low human density. Evidence to suggest this comes largely from radio telemetry data from both blue racers and eastern fox snakes that inhabited the same general areas on Pelee Island (although studies were not conducted concurrently). In contrast to blue racers, fox snakes were often found under front porches, in barns/garages, and in the foundations of houses; whereas, most (but not all) blue racers were observed in more "natural" settings. Therefore, blue racers are more confined to areas with minimal anthropogenic activity. Campbell and Perrin also noted that racers were among the first snakes to disappear from suburban areas.[1]

Blue racers are active foragers.The younger snakes may consume crickets and other insects, whereas adults feed primarily on rodents, songbirds, and snakes. Adults engage in both terrestrial and arboreal foraging. Blue racers are diurnally active. Probable natural predators of adult blue racers include the larger birds of prey (e.g., red-tailed hawk, northern harrier, great horned owl) and carnivorous mammals such as raccoons, foxes, and coyotes. Dogs and feral house cats are known to kill and/or harass juvenile blue racers. The eggs and young are likely vulnerable to a wider variety of avian and mammalian predators.[1]

Reproduction

The blue racer is oviparous and average clutch size for seven females is 14.7 ± 2.53. Females can reproduce annually, but biennial cycles are likely more common. Males can mature physiologically at 11 months but do not have the opportunity to mate until their second full year; similarly, females may mature at 24 months but are not be able to reproduce until the following year. Mating begins in April and continues throughout May. Females oviposit in late June and eggs hatch from mid-August to late-September. The most common nesting microhabitats used by female blue racers are fallen decaying logs; however, eggs are also laid under large rocks, and in mounds of decaying organic matter. Intra- and interspecific (with eastern fox snake) communal nest sites have been documented and appear to be relatively common.[1]

Conservation

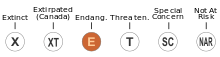

The snake has not yet been assessed for the IUCN Red List in terms of conservation, but is listed as endangered in Canada by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada.[1] It is listed as a species of special concern in the state of Wisconsin[2]

The blue racer has been on Ontario's Endangered Species List since 1971. Consequently, habitat determined to be critical to the snake's persistence is protected (from destruction or significant alteration) under Ontario's Endangered Species Act (ESA). In 1998, blue racer "habitat" on Pelee Island was spatially delineated (primarily utilizing mark-recapture and radio telemetry data collected from 1990–1998), and formally identified for the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). Subsequent to the spatial delineation (or mapping) of this habitat, the OMNR determined that these lands should be protected from destruction or human interference as is required under the ESA. The habitat protection afforded by the ESA has significant land use implications, particularly because a substantial percentage of blue racer habitat identified occurs on private lands. Unfortunately, implementing a program to effectively protect endangered species habitat on private lands has been extremely difficult.Several areas known to harbour blue racers and the important microhabitats used by them (e.g., hibernacula) are formally protected on Pelee Island. Lighthouse Point Provincial Nature Reserve and the Stone Road Alvar Complex (owned and managed by the Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Essex Region Conservation Authority, and Nature Conservancy Canada) are the two most important protected areas for the blue racer.[1]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coluber constrictor. |

- COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Canada

- Racer - Coluber constrictor — Species account from the Iowa Reptile and Amphibian Field Guide

- University of Michigan, Animal Diversity Web: Coluber constrictor

- Species Coluber constrictor at The Reptile Database