Coltivirus

| Coltivirus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group III (dsRNA) |

| Order: | Unassigned |

| Family: | Reoviridae |

| Subfamily: | Spinareovirinae |

| Genus: | Coltivirus |

| Type species | |

| Colorado tick fever virus | |

| Species | |

|

Colorado tick fever virus | |

Coltivirus is a genus of viruses (belonging to the Reoviridae family) that infects vertebrates, invertebrates, and plants. It includes the causative agent of Colorado tick fever.[1] Colorado tick fever virus can cause a fever, chills, headache, photophobia, myalgia, arthralgia, and lethargy. Children, in particular, may develop a hemorrhagic disease. Leukopenia with both lymphocytes and neutrophils is very common for Colorado tick fever virus. In either case, the infection can lead to encephalitis or meningitis.[2]

What is Coltivirus?

Coltivirus is a genus of viruses. Viruses are intracellular parasites that do not have the necessary means to reproduce on their own, so they have to hijack the machinery of a host cell instead. Only then can they synthesize their viral proteins and make progeny. There are two types of viruses, distinguished by their type of genetic material. DNA viruses have genomes consisting of deoxyribonucleic acid (or DNA), while RNA viruses, like Coltivirus, have an RNA (ribonucleic acid) genome.[3]

General Description

The name “Coltivirus” is derived from the main member in the family, the Colorado tick fever virus (“Colorado tick”). Coltivirus is in the family Reoviridae, which contains eight genera. Orthoreovirus, Orbivirus, Coltivirus, Rotavirus, Aquareovirus, Cypovirus, Phytoreovirus, and Fijivirus.[4] Coltivirus and Orbivirus together contain about 109 serotypes, and only four of these cause human disease.[4] Ticks are the main vectors of Coltiviruses (5). The type species of Coltivirus is Colorado tick fever virus, but European Eyach virus is another member of the genus.[5] Colorado tick fever was originally recorded in the 19th century, and today it is one of the most common tick-borne diseases in the United States.[2]

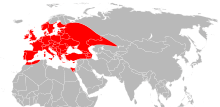

The European Eyach virus and the Colorado tick fever virus are known relatives due to cognate genes, 55% to 88% of amino acid similarity, and similarities at the microscopic level that cannot be distinguished.[5] To find these similarities, a genome sequence analysis was completed.[6] One theory of how the European Eyach virus is proposed to have come about in Europe is by the migration of lagomorphs from North America over fifty million years ago.[5] Since then, the virus took on some differences, and is now considered its own species of virus. European Eyach virus was isolated in 1976 from Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe and in 1981 from the same species along with Ixodes ventalloi in 1981.

Other Characteristics

Morphology and Physiology of the Virus

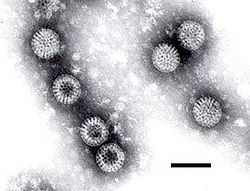

The Coltivirus virions are about 60-80 nanometers in diameter and are not enveloped, and are generally a spherical shape with icosahedral symmetry. Each virion has two concentric capsid shells surrounding a core of about 50 nanometers in diameter. The surface of the particle is relatively smooth.[6] The virus loses its infectivity when the surrounding fluid becomes acidic, around a pH of three, but is stable when the pH is between seven and eight. It also stops being a threat when the temperature becomes about fifty-five degrees Celsius.[6]

Genome and Genomic Organization

Coltiviruses have twelve segments of linear, double-stranded RNA. When the genome is processed with gel electrophoresis, the segments migrate as three class sizes (three bands). Each segment is replicated, and the largest segment encodes RNA polymerase.[6] Locations of other proteins along the genome have yet to be determined.

Pathogenesis and Viral Reproduction

Coltiviruses replicate in the cytoplasm in cells of both arthropods and vertebrates, but they are only transmitted by the arthropods.[4] When the virus replicates, the virion outer shell has to be removed in order for RNA polymerase to be activated to continue the replication of the virion’s RNA. Reassortment of the RNA segments in progeny is common, and this plays a role in some of the genetic diversity between the serotypes. Sometimes, this can lead to fast changes in the properties of the viruses.[4]

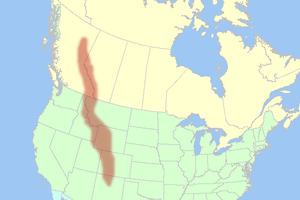

The main species of Coltivirus, Colorado tick fever virus (CTF), infects the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni). This species of tick can be found in areas with shrubs, lightly wooded locations, grasslands, and on hiking or biking trails. All life stages of this tick can infect vertebrates with Colorado tick fever virus (larva, nymph, and adult). Unfortunately, mature D. andersoni prefer to feed on medium or large mammals that are walking around the knee-high plants.[7] Often times, this infection takes place when the tick larvae feed on rodents, like squirrels, that are already infected with virus. The tick’s saliva then contains the virus, and it becomes infectious for life. The adult tick then transmits the virus to humans through a bite, where it infects bone marrow cells.[4]

The virus replicates in those bone marrow cells, which disrupts the development and replication of leukocytes (white blood cells), eosinophils, and basophils. Because of this, thrombocytopenia could also a potential result. Erythrocytes, which are enucleated red blood cells, seem to be infected while they are erythroblasts, their nucleated precursor stage.[4] The virus stays in these red blood cells without harming it for up to four months.[6] Here, it is protected from the immune system’s attacks.[2] Antibody to the virus is found only about two weeks after symptoms begin to show, but the virus can still be found in blood cells for about six weeks.[4]

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Colorado Tick Fever Virus (CTFV)

Colorado tick fever virus can cause a fever, chills, headache, photophobia, myalgia, arthralgia, and lethargy. Children, in particular, may develop a hemorrhagic disease. Leukopenia with both lymphocytes and neutrophils is very common for Colorado tick fever virus. In either case, the infection can lead to encephalitis or meningitis.[2]

For diagnosis, the erythrocytes can be isolated by injecting them into a tissue culture and checking to see if they are infected. Also, the antigen for Colorado tick fever virus can be identified using the immunofluorescence microscopy. In this method, the antigens on the surface of the erythrocytes are marked with fluorescence and examined under a fluorescence microscope.[4]

Epidemiology and Control

The distribution of Colorado tick fever virus is in the Rocky Mountain area of the United States at elevations between four and ten thousand feet.[6] Not surprisingly, Colorado tick fever virus can be found in places like California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, British Columbia, and Alberta. This is roughly the same distribution as the tick that transmits the virus, showed in the picture to the right.[4]

The virus circulates between ticks and rodents, with humans being the secondary hosts.[4] People at risk for catching the disease are hikers and campers that are in the risk areas. Also, April, May, and June are when the infections mainly occur, because this is the time when the adult ticks are prevalent in the environment. Unfortunately, this is also when the weather is pleasant for hiking and camping. The best way to avoid getting bitten and catching this disease is wearing long sleeves or pants, avoiding high tick-infested areas, and wearing tick repellent.[4]

Treatment

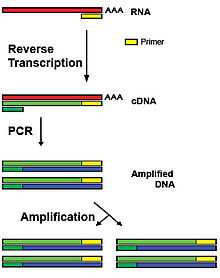

Colorado tick fever virus can be detected in a patient with a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), where even a single virion and its genetic material can be detected.[6] The antigens to the virus can also be detected using immunofluorescence.[4] There is currently no known vaccine or treatment available to treat these Coltiviruses, but 3’-fluors-3’-deoxyadanosine, a nucleoside analog, halts replication of Colorado tick fever virus in vitro.[4]

References

- ↑ Attoui H, Charrel RN, Billoir F, Cantaloube JF, de Micco P, de Lamballerie X (1998). "Comparative sequence analysis of American, European and Asian isolates of viruses in the genus Coltivirus". J. Gen. Virol. 79 (10): 2481–9. PMID 9780055.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Murray, PR, Rosenthal, KS, and Pfaller, MA. (2013). "Coltiviruses and Orbiviruses: Chapter 59.". Medical Microbiology (7 ed.).

- ↑ Lodish, Berk, Kaiser, Krieger, Bretscher, Ploegh, Amon, and Scott (2013). Molecular Biology. W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 160.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12 Kapikian AZ, Shope RE, Baron S editor (1996). "Rotaviruses, reoviruses, coltiviruses, and orbiviruses: Chapter 63.". Medical Microbiology (4 ed.). PMID 21413350.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Attoui H, Mohd Jaafar F, Biagini P, Cantaloube JF, de Micco P, Murphy FA, de Lamballerie X (March 2002). "Genus Coltivirus (family Reoviridae): genomic and morphologic characterization of Old World and New World viruses". ’’Arch Virol’’ 143 (3): 533–61. PMID 11958454.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Attoui H, Mohd Jaafar F, de Micco P, de Lamballerie X. (Nov 2005). "Coltiviruses and seadornaviruses in North America, Europe, and Asia". Emerg Infect Dis 11 (11): 1673–1679. doi:10.3201/eid1111.050868. PMC 3367365. PMID 16318717.

- ↑ University of Rhode Island TickEncounter Resource Center (2014). "Dermacentor andersoni, Rocky Mountain wood tick".