College football

College football is gridiron football played by teams of student athletes fielded by American universities, colleges, and military academies, or Canadian football played by teams of student athletes fielded by Canadian universities. It was through college football play that American football rules first gained popularity in the United States.

History

Rugby Football in England and Canada

Modern North American football has its origins in various games, all known as "football", played at public schools in England in the mid-19th century. By the 1840s, students at Rugby School were playing a game in which players were able to pick up the ball and run with it, a sport later known as Rugby football. The game was taken to Canada by British soldiers stationed there and was soon being played at Canadian colleges.

The first documented gridiron football match was a game played at University College, a college of the University of Toronto, November 9, 1861. One of the participants in the game involving University of Toronto students was (Sir) William Mulock, later Chancellor of the school. A football club was formed at the university soon afterward, although its rules of play at this stage are unclear.

In 1864, at Trinity College, also a college of the University of Toronto, F. Barlow Cumberland and Frederick A. Bethune devised rules based on rugby football. Modern Canadian football is widely regarded as having originated with a game played in Montreal, in 1865, when British Army officers played local civilians. The game gradually gained a following, and the Montreal Football Club was formed in 1868, the first recorded non-university football club in Canada.

First American college football game

The first intercollegiate football game played under the rules that would eventually become modern American football rules occurred between Princeton University and Rutgers University (which was called Rutgers College at the time) on November 6, 1869. However, this game was far more like soccer than modern American football. The completion of the first ever American football season came as a result of only two total games being played.

The Princeton-Rutgers game took place on College Field, which is now the site of the College Avenue Gymnasium at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers won by a score of 6 "runs" to Princeton's 4.[1][2] The 1869 game between Rutgers and Princeton is the first documented game of intercollegiate "football" ever played between two American colleges, and because of this, Rutgers refers to itself as The Birthplace of College Football. It came two years before the founding of the Rugby Football Union in England, even though rugby had been codified 24 years before this in 1845 and played by many schools, universities, and clubs. Although the Rutgers-Princeton game was undoubtedly different from what we know today as American football, it was the forerunner of what evolved into American football. Another similar game took place between Rutgers and Columbia University in 1870.

Less than six years after that first game, a game that more closely resembled modern American football occurred between Harvard University and Tufts University on June 4, 1875. Though Harvard vs. Tufts is regarded as the first intercollegiate American football game between US teams, a game played by roughly the same rules (the so-called "Boston Rules") occurred between Harvard and McGill University of Montreal in 1874.[3] Harvard, who was trying to get away from the soccer-like game that many schools played, set out to find another school who played a game similar to the one they did. This first game was a lot like rugby but much closer to modern day football than soccer. After the captains of the two teams met, they quickly realized that the games each school played were still different. In a compromise, the teams decided to play two different games, one under each team's set of rules. On May 14, Harvard won the game under their rules, and on the following day, May 15, the game under McGill's rules ended in a scoreless tie. Harvard would eventually go on to fully adopt the McGill version of the game that included more carrying of the ball and also used an oblong ball that was easier to carry and throw.[EBSCOhost 1] An 1869 game of intercollegiate "football" between Rutgers and Princeton is often cited as the first intercollegiate American football game, however it was an unfamiliar ancestor of today's college football, as it was played under 6-year-old soccer-style Association rules.[4]

Rugby is adopted by American colleges

Rutgers, Princeton and Columbia met on October 20, 1873 at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City to agree on a set of rules and regulations that would allow them to play a form of football that was essentially Association football (today often called "soccer" in the US) in character. Harvard University turned down an invitation to join this group because they preferred to play a rougher version of football called "the Boston Game" in which the kicking of a round ball was the most prominent feature though a player could run with the ball, pass it, or dribble it (known as “babying”). The man with the ball could be tackled, although hitting, tripping, “hacking” (shin-kicking) and other unnecessary roughness was prohibited. There was no limit to the number of players, but there were typically ten to fifteen per side.

Harvard's decision not to join the Yale-Rutgers-Princeton-Columbia association meant that they needed to look further afield to find football opponents so when a challenge from Canada’s McGill University rugby team in Montreal was issued to Harvard, they accepted. It was agreed that two games would be played on Harvard’s Jarvis baseball field in Cambridge, Massachusetts on May 14 and 15, 1874: one to be played under Harvard rules, another under the stricter rugby regulations of McGill. Harvard beat McGill in the "Boston Game" on the Thursday and held McGill to a 0-0 tie on the Friday. The Harvard students took to the rugby rules and adopted them as their own,[5] travelling to Montreal to play a further game of rugby in the Fall of the same year winning by three tries to nil.

Harvard then played Tufts University on June 4, 1875, again at Jarvis Field. Jarvis Field was at the time a patch of land at the northern point of the Harvard campus, bordered by Everett and Jarvis Streets to the north and south, and Oxford Street and Massachusetts Avenue to the east and west. The game was won by Tufts 1-0[6] and a report of the outcome of this game appeared in the Boston Daily Globe of June 5, 1875. In this game each side fielded eleven men, participants were allowed to pick up the inflated egg-shaped ball and run with it and the ball carrier was stopped by knocking him down or "tackling" him. A photograph of the 1875 Tufts team which hangs in the College Football Hall of Fame commemorates this match as the generally accepted first intercollegiate football game between two US institutions.[7]

In 1876 at Massasoit House in Springfield, Massachusetts, Harvard persuaded Princeton and Columbia to adopt an amalgam of rugby's laws and the rules that they were then playing, thus forming the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA). Yale initially refused to join this association because of a disagreement over the number of players to be allowed per team (relenting in 1879) and Rutgers were not invited to the meeting. The rules that they agreed upon were essentially those of rugby union at the time with the exception that points be awarded for scoring a try, not just the conversion afterwards (extra point). Incidentally, rugby was to make a similar change to its scoring system 10 years later.

Rugby becomes American football

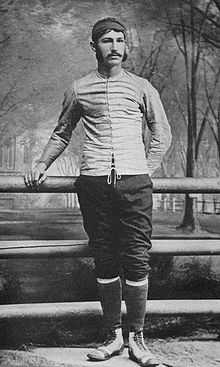

Walter Camp, known as the "Father of American Football", is credited with changing the game from a variation of rugby into a unique sport. Camp, who was a rugby coach, decided to come up with a new set of rules to create a game that was completely different. Camp is responsible for pioneering the play from scrimmage with initially uncontested possession for the team starting with the ball (earlier games featured a rugby scrum where possession was contested) and was also the one who decided that teams should have 4 downs to advance the ball ten yards. Camp was responsible for the eleven-man team.[EBSCOhost 1] Camp also had a hand in popularizing the game. He published numerous articles in publications such as Collier's Weekly and Harper's Weekly, and he chose the first College Football All-America Team.

Formation of the NCAA

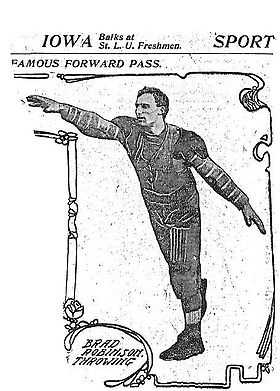

College football increased in popularity through the remainder of the 19th century. It also became increasingly violent. Between 1890 and 1905, 330 college athletes died as a direct result of injuries sustained on the football field. These deaths could be attributed to the mass formations and gang tackling that characterized the sport in its early years. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt organized a meeting among thirteen school leaders at the White House to find solutions to make the sport safer for the athletes. Because the college officials could not agree upon a change in rules, it was decided over the course of several subsequent meetings that an external governing body should be responsible. Resulting from this conference was the formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States in 1906. The IAAUS was the original rule making body of college football, but would go on to sponsor championships in other sports. The IAAUS would get its current name of National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), in 1910 which still sets rules governing the sport.[8] The rules committee considered widening the playing field to "open up" the game, but Harvard Stadium (the first large permanent football stadium) had recently been built at great expense; it would be rendered useless by a wider field. The rules committee legalized the forward pass instead. The first legal pass was thrown by Bradbury Robinson on September 5, 1906, playing for coach Eddie Cochems, who developed an early but sophisticated passing offense at Saint Louis University. Another rule change banned "mass momentum" plays (many of which, like the infamous "flying wedge", were sometimes literally deadly).

Even after the emergence of the professional National Football League (NFL), college football remained extremely popular throughout the U.S.[9] Although the college game has a much larger margin for talent than its pro counterpart, the sheer number of fans following major colleges provides a financial equalizer for the game, with Division I programs – the highest level – playing in huge stadiums, six of which have seating capacity exceeding 100,000. In many cases, college stadiums employ bench-style seating, as opposed to individual seats with backs and arm rests. This allows them to seat more fans in a given amount of space than the typical professional stadium, which tends to have more features and comforts for fans. (Only two stadiums owned by U.S. colleges or universities—Papa John's Cardinal Stadium at the University of Louisville and FAU Stadium at Florida Atlantic University—consist entirely of chairback seating.)

College athletes, unlike players in the NFL, are not permitted by the NCAA to be paid salaries. Colleges are only allowed to provide non-monetary compensation such as athletic scholarships that provide for tuition, housing, and books.[10]

Official rules and notable rule distinctions

Although rules for the high school, college, and NFL games are generally consistent, there are several minor differences. The NCAA Football Rules Committee determines the playing rules for Division I (both Bowl and Championship Subdivisions), II, and III games (the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) is a separate organization, but uses the NCAA rules).

- A pass is ruled complete if one of the receiver's feet is inbounds at the time of the catch. In the NFL both feet must be inbounds.

- A player is considered down when any part of his body other than the feet or hands touches the ground or when the ball carrier is tackled or otherwise falls and loses possession of the ball as he contacts the ground with any part of his body, with the sole exception of the holder for field goal and extra point attempts. In the NFL a player is active until he is tackled or forced down by a member of the opposing team (down by contact).

- The clock stops after the offense completes a first down and begins again—assuming it is following a play in which the clock would not normally stop—once the referee says the ball is ready for play. In the NFL the clock does not explicitly stop for a first down.

- Overtime was introduced in 1996, eliminating ties. When a game goes to overtime, each team is given one possession from its opponent's twenty-five yard line with no game clock, despite the one timeout per period and use of play clock. The team leading after both possessions is declared the winner. If the teams remain tied, overtime periods continue, with a coin flip determining the first possession. Possessions alternate with each overtime, until one team leads the other at the end of the overtime. Starting with the third overtime, a one point PAT field goal after a touchdown is no longer allowed, forcing teams to attempt a two-point conversion after a touchdown. (In the NFL overtime is decided by a 15-minute sudden-death quarter, and regular season games can still end in a tie if neither team scores. Overtime for regular season games in the NFL began with the 1974 season. In the post-season, if the teams are still tied, teams will play additional overtime periods until either team scores.)

- Extra point tries are attempted from the three-yard line. The NFL uses the two-yard line. This counts as one point. Teams can also go for "the two-point conversion" which is when a team will line up at the three-yard line and try to score. If they are successful, they receive two points, if they are not, then they receive zero points. The two-point conversion was not implemented in the NFL until 1994, but it had been previously used in the old American Football League (AFL) before it merged with the NFL in 1970.

- The defensive team may score two points on a point-after touchdown attempt by returning a blocked kick, fumble, or interception into the opposition's end zone. In addition, if the defensive team gains possession, but then moves backwards into the endzone and is stopped, a one point safety will be awarded to the offense, although, unlike a real safety, the offense kicks off, opposed to the team charged with the safety. This college rule was added in 1988. In the NFL, a conversion attempt ends when the defending team gains possession of the football.

- The two-minute warning is not used in college football, except in rare cases where the scoreboard clock has malfunctioned and is not being used.

- There is an option to use instant replay review of officiating decisions. Division I FBS (formerly Division I-A) schools use replay in virtually all games; replay is rarely used in lower division games. Every play is subject to booth review with coaches only having one challenge. In the NFL, only scoring plays, turnovers, the final 2:00 of each half and all overtime periods are reviewed, and coaches are issued two challenges (with the option for a 3rd if the first two are successful).

- Starting in the 2012 season, the ball is placed on the 25-yard line following a touchback on a kickoff. At all other levels of football, plus all other touchback situations under NCAA rules, the ball is placed on the 20.

- Among other rule changes in 2007, kickoffs were moved from the 35-yard line back five yards to the 30-yard line, matching a change that the NFL had made in 1994. Some coaches and officials questioned this rule change as it could lead to more injuries to the players as there will likely be more kickoff returns.[11] The rationale for the rule change was to help reduce dead time in the game.[12] The NFL returned its kickoff location to the 35-yard line effective in 2011; college football did not do so until 2012.

- Several changes were made to college rules in 2011, all of which differ from NFL practice:[13]

- If a player is penalized for unsportsmanlike conduct for actions that occurred during a play ending in a touchdown by that team, but before the goal line was crossed, the touchdown will be nullified. In the NFL, the same foul would result in a penalty on the conversion attempt or ensuing kickoff, at the option of the non-penalized team.

- If a team is penalized in the final minute of a half and the penalty causes the clock to stop, the opposing team now has the right to have 10 seconds run off the clock in addition to the yardage penalty. The NFL has a similar rule in the final minute of the half, but it applies only to specified violations against the offensive team. The new NCAA rule applies to penalties on both sides of the ball.

- Players lined up outside the tackle box—more specifically, those lined up more than 7 yards from the center—will now be allowed to block below the waist only if they are blocking straight ahead or toward the nearest sideline.

- On placekicks, no offensive lineman can now be engaged by more than two defensive players. A violation will be a 5-yard penalty.

Organization

College teams mostly play other similarly sized schools through the NCAA's divisional system. Division I generally consists of the major collegiate athletic powers with larger budgets, more elaborate facilities, and (with the exception of a few conferences such as the Pioneer Football League) more athletic scholarships. Division II primarily consists of smaller public and private institutions that offer fewer scholarships than those in Division I. Division III institutions also field teams, but do not offer any scholarships.

Football teams in Division I are further divided into the Bowl Subdivision (consisting of the largest programs) and the Championship Subdivision. The Bowl Subdivision has historically not used an organized tournament to determine its champion, and instead teams compete in post-season bowl games. (That will change with the debut of the four-team College Football Playoff in 2015.)

Teams in each of these four divisions are further divided into various regional conferences.

Several organizations operate college football programs outside the jurisdiction of the NCAA:

- The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics has jurisdiction over more than 80 college football teams, mostly in the midwest.

- The National Junior College Athletic Association has jurisdiction over two-year institutions. (California's two-year institutions are not under NJCAA jurisdiction and only compete for state championships.)

- Club football, a sport in which student clubs run the teams instead of the colleges themselves, is overseen by two organizations: the National Club Football Association and the Intercollegiate Club Football Federation. The two competing sanctioning bodies have some overlap, and several clubs are members of both organizations.

- The Collegiate Sprint Football League governs nine teams, all in the northeast. Its primary restriction is that all players must weigh less than the average college student (that threshold is set, as of 2015, at 172 pounds).

A college that fields a team in the NCAA is not restricted from fielding teams in club or sprint football, and several colleges field two teams, a varsity (NCAA) squad and a club or sprint squad (no schools, as of 2014, field both club and sprint teams at the same time).

Coaching

National championships

- College football national championships in NCAA Division I FBS - Overview of systems for determining national champions at the highest level of college football from 1869 to present.

- College Football Playoff - 4 team playoff system for determining national champions at the highest level of college football beginning in 2014.

- Bowl Championship Series - The primary method of determining the national champion at the highest level of college football from 1998-2013; preceded by the Bowl Alliance (1995-1997) and the Bowl Coalition (1992-1994).

- NCAA Division I Football Championship[14] - playoff for determining the national champion at the second highest level of college football, Division I FCS, from 1978 to present.

- NCAA Division I FCS Consensus Mid-Major Football National Championship - awarded by poll from 2001- to 2007 for a subset of the second highest level of play in college football, FCS.

- NCAA Division II National Football Championship - playoff for determining the national champion at the third highest level of college football from 1973 to present.

- NCAA Division III National Football Championship - playoff for determining the national champion at the fourth highest level of college football from 1973 to present.

- NAIA National Football Championship -playoff for determining the national champions of college football governed by the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics.

- NJCAA National Football Championship - playoff for determining the national champions of college football governed by the National Junior College Athletic Association.

- CSFL Championship - Champions of the Collegiate Sprint Football League, a weight restricted football sport.

Team maps

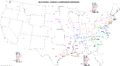

Updated Map of NCAA FBS Schools

-

Map of Division I (A) FBS

-

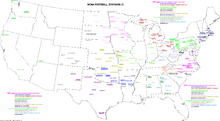

Map of Division I (AA) FCS

-

Map of NCAA Division II

-

Map of NCAA Division III

-

Map of NAIA

-

Map of NJCAA

-

Map of CCCAA

Playoff games

Starting in the 2014 season, four Division I FBS teams will be selected at the end of regular season to compete in a playoff for the FBS national championship. The College Football Playoff will replace the Bowl Championship Series, which had been used as the selection method to determine the national championship game participants starting in the 1998 season.

At the Division I FCS level, the teams participate in a 24-team playoff (most recently expanded from 20 teams in 2013) to determine the national championship. Under the current playoff structure, the top eight teams are all seeded, and receive a bye week in the first round. The highest seed receives automatic home field advantage. Starting in 2013, non-seeded teams can only host a playoff game if both teams involved are unseeded; in such a matchup, the schools must bid for the right to host the game. Selection for the playoffs is determined by a selection committee, although usually a team must have a 7-4 record to even be considered. Losses to an FBS team count against their playoff eligibility, while wins against a Division II opponent do not count towards playoff consideration. Thus, only Division I wins (whether FBS, FCS, or FCS non-scholarship) are considered for playoff selection. The Division I National Championship game is held in Frisco, Texas.

Division II and Division III of the NCAA also participate in their own respective playoffs, crowning national champions at the end of the season. The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics also holds a playoff.

Bowl games

Unlike other college football divisions and most other sports—collegiate or professional—the Football Bowl Subdivision, formerly known as Division I-A college football, has historically not employed a playoff system to determine a champion. Instead, it has a series of postseason "bowl games". The annual National Champion in the Football Bowl Subdivision is then instead traditionally determined by a vote of sports writers and other non-players.

This system has been challenged often, beginning with an NCAA committee proposal in 1979 to have a four-team playoff following the bowl games.[15] However, little headway was made in instituting a playoff tournament until 2014, given the entrenched vested economic interests in the various bowls. Although the NCAA publishes lists of claimed FBS-level national champions in its official publications, it has never recognized an official FBS national championship; this policy will continue even after the establishment of the College Football Playoff (which will not be directly run by the NCAA) in 2014. As a result, the official Division I National Champion is the winner of the Football Championship Subdivision, as it is the highest level of football with an NCAA-administered championship tournament.

The first bowl game was the 1902 Rose Bowl, played between Michigan and Stanford; Michigan won 49-0. It ended when Stanford requested and Michigan agreed to end it with 8 minutes on the clock. That game was so lopsided that the game was not played annually until 1916, when the Tournament of Roses decided to reattempt the postseason game. The term "bowl" originates from the shape of the Rose Bowl stadium in Pasadena, California, which was built in 1923 and resembled the Yale Bowl, built in 1915. This is where the name came into use, as it became known as the Rose Bowl Game. Other games came along and used the term "bowl", whether the stadium was shaped like a bowl or not.

At the Division I FBS level, teams must earn the right to be bowl eligible by winning at least 6 games during the season (teams that play 13 games in a season, which is allowed for Hawaii and any of its home opponents, must win 7 games). They are then invited to a bowl game based on their conference ranking and the tie-ins that the conference has to each bowl game. For the 2009 season, there were 34 bowl games, so 68 of the 120 Division I FBS teams were invited to play at a bowl. These games are played from mid-December to early January and most of the later bowl games are typically considered more prestigious.

After the Bowl Championship Series, additional all-star bowl games round out the post-season schedule through the beginning of February.

Division I FBS National Championship Games

Partly as a compromise between both bowl game and playoff supporters, the NCAA created the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) in 1998 in order to create a definitive National Championship game for college football. The series included the four most prominent bowl games (Rose Bowl, Orange Bowl, Sugar Bowl, Fiesta Bowl), while the National Championship game rotated each year between one of these venues. The BCS system was slightly adjusted in 2006, as the NCAA added a fifth game to the series, called the National Championship Game. This allowed the four other BCS bowls to use their normal selection process to select the teams in their games while the top two teams in the BCS rankings would play in the new National Championship Game.

The BCS selection committee used a complicated, and often controversial, computer system to rank all Division 1-FBS teams and the top two teams at the end of the season played for the National Championship. This computer system, which factored in newspaper polls, online polls, coaches' polls, strength of schedule, and various other factors of a team's season, led to much dispute over whether the two best teams in the country were being selected to play in the National Championship Game.

The BCS ended after the 2013 season and, starting in the 2014 season, the FBS national champion will be determined by a four-team playoff known as the College Football Playoff (CFP). A selection committee of college football experts will decide the participating teams. Six major bowl games (the Rose, Sugar, Cotton, Orange, Peach, and Fiesta) will rotate on a three-year cycle as semifinal games, with the winners advancing to the College Football Playoff National Championship. This arrangement is contractually locked in until the 2026 season.

Controversy

College football is a controversial institution within American higher education, where the amount of money involved -- what people will pay for the entertainment provided -- is a corrupting factor within universities that they are usually ill-equipped to deal with.[16][17] According to William E. Kirwan, chancellor of the University of Maryland System and co-director of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, "We've reached a point where big-time intercollegiate athletics is undermining the integrity of our institutions, diverting presidents and institutions from their main purpose."[18] Football coaches often make more than the presidents of their universities which employ them.[19] Athletes are alleged to receive preferential treatment both in academics and when they run afoul of the law.[20] Although in theory football is an extra-curricular activity engaged in as a sideline by students, it generates a substantial profit, from which the athletes receive no direct benefit. There has been serious discussion about making student-athletes university employees to allow them to be paid.[21][22][23][24]

College football outside the United States

Canadian football, which parallels American football, is played by collegiate teams in Canada under the auspices of Canadian Interuniversity Sport. (Unlike in the United States, no junior colleges play football in Canada, and the sanctioning body for junior college athletics in Canada, CCAA, does not sanction the sport.) However, amateur football outside of colleges is played in Canada, such as in the Canadian Junior Football League. Organized competition in American football also exists at the collegiate level in Mexico (ONEFA), the UK (British Universities American Football League), Japan (Japan American Football Association, Koshien Bowl), and South Korea (Korea American Football Association).

Awards

|

See also

References

- ↑ Rutgers Through the Years (timeline), published by Rutgers University (no further authorship information available), accessed 12 January 2007.

- ↑ Tradition at www.scarletknights.com. Published by Rutgers University Athletic Department (no further authorship information available), accessed 10 September 2006.

- ↑ "Citing Research, Tufts Claims Football History is on its Side". Boston Globe. 23 September 2004. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ http://www.scarletknights.com/football/history/first-game.asp - note that The Football Association's rules were adopted at the time

- ↑ Infamous 1874 McGill-Harvard game turns 132 at McGill Athletics, published by McGill University (no further authorship information available). This article incorporates text from the McGill University Gazette (April 1874), two issues of The Montreal Gazette (14 May and 19 May 1874). Accessed 29 January 2007.

- ↑ Smith, R.A. "Sports and Freedom: The Rise of Big-Time College Athletics", New York: Oxford University Press, 1988

- ↑ Carzo, Rocco J. "Jumbo Footprints: A History of Tufts Athletics", Medford, MA: Tufts University Gallery, 2005; summarized in Another 'Pass' At History by Tufts University eNews on 27 September 2004. Accessed 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "University of Florida Health Science Center Libraries". Web.ebscohost.com.lp.hscl.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ While Still the Nation's Favorite Sport, Professional Football Drops in Popularity - Baseball and college football are next in popularity at the Harris Interactive website, accessed 28 January 2010.

- ↑ "University of Florida Health Science Center Libraries" (PDF). Journals.humankinetics.com.lp.hscl.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "Kickoffs from 30 yard line could create more returns, injuries". Associated Press. April 16, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ↑ "NCAA Football Rules Committee Votes To Restore Plays While Attempting To Maintain Shorter Overall Game Time". NCAA. 2007-02-14. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ↑ "Series of rules changes approved". ESPN.com. Associated Press. April 15, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ↑ NCAA Division I Football Championship - Official Web Site

- ↑ White, Gordon (January 8, 1979). "N.C.A.A. Committee Urges Football Playoff". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ Steven Salzberg, "Football is corrupting America's universities: it needs to go", Forbes, November 26, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevensalzberg/2011/11/26/football-is-corrupting-americas-universities-it-needs-to-go/

- ↑ Jay Schalin, "Time for universities to punt football", Washington Times, September 1, 2011, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2011/sep/1/time-for-universities-to-punt-football/?page=all

- ↑ Laura Pappano, "How Big-Time Sports Ate College Life", New York Times, January 20, 2012.

- ↑ Jonah Newman, "Coaches, Not Presidents, Top Public-College Pay List", Chronicle of Higher Education, May 16, 2014, http://chronicle.com/blogs/data/2014/05/16/coaches-not-presidents-top-public-college-pay-list/

- ↑ One reference among many: Walt Bogdanich, "A Star Player Accused, and a Flawed Rape Investigation", New York Times, April 16, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/04/16/sports/errors-in-inquiry-on-rape-allegations-against-fsu-jameis-winston.html

- ↑ Gregg Doyel, "Time to pay college football players -- changing times, money say so", CBS Sports, September 25, 2013, http://www.cbssports.com/general/writer/gregg-doyel/23838595/its-time-pay-college-football-players----changing-times-money-say-so

- ↑ Rod Gilmore, "College football players deserve pay for play", ESPN College Football, January 17, 2007, http://sports.espn.go.com/ncf/columns/story?id=2733624

- ↑ Taylor Branch, "The Shame of College Sports", The Atlantic, October, 2011, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/10/the-shame-of-college-sports/308643/

- ↑ Ben Strauss and Marc Tracy, "N.C.A.A. Must Allow Colleges to Pay Athletes, Judge Rules", New York Times, August 8, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/sports/federal-judge-rules-against-ncaa-in-obannon-case.html

See also

- The Invention Of Football. Current Events, 00113492, 11/14/2011, Vol. 111, Issue 8

- Brian M. Ingrassia, The Rise of Gridiron University: Higher Education's Uneasy Alliance with Big-Time Football. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to College football. |

Statistics

- College Football at d1sportsnet.com

- College Football at Sports-Reference.com

- Stassen College Football, comprehensive college football database

- College Football Data Warehouse

- Gridiron History

Rules

Maps

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||