Coffee palace

The term Coffee Palace was primarily used in Australia to describe the temperance hotels which were built during the period of the 1880s[1] although there are references to the term also being used, to a lesser extent, in the United Kingdom. They were hotels that did not serve alcohol, built in response to the temperance movement and, in particular, the influence of the Independent Order of Rechabites in Australia. James Munro was a particularly vocal member of this movement. Coffee Palaces were often multi-purpose or mixed use buildings which included a large number of rooms for accommodation as well as ballrooms and other function and leisure facilities.

The beginnings of the movement were in 1879, with the first coffee palace companies founded in the cities of Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide. The movement in particular flourished in Melbourne in the 1880s when a land boom that followed the Victorian gold rush created an environment in which it was the construction of lavish buildings and richly ornamental high Victorian architecture, often designed in the fashionable Free Classical or Second Empire styles to attract patrons. Many of the larger establishments were bestowed prestigious names such as "Grand" or "Royal" in order to appeal to the wealthier classes.

Coffee palaces were popular in the coastal seaside resorts and for inner city locations attracting catering for families as well as interstate and overseas visitors.

Ironically as the temperance movement's influence waned, many of these coffee palaces applied for liquor licences. Many have since been either converted into hotels or demolished; however, some significant examples still survive.

Australia

Victoria

Melbourne

- Collingwood Coffee Palace. 232 Smith Street, Collingwood (now in Fitzroy) (1879 – constructed as a four storey building) (demolished - though two levels of the facade remain atop a Woolworths supermarket)

- Brunswick Coffee Palace, Brunswick (1879)[2]

- The Coffee Palace. Flinders Street. (1880)[3]

- Victoria Coffee Palace. Collins Street East (1880 - began as the Victoria Club) (demolished)

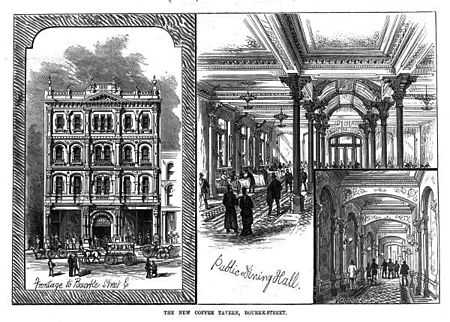

- Melbourne Coffee Palace. Bourke Street. (1881)

- Grand Coffee Palace (1883) (later named Windsor)

- Gladstone House Coffee Palace, North Melbourne

- The Biltmore, Albert Park (1887)

- Victoria, Albert Park

- The George, St Kilda (1887)

- Mentone Coffee Palace, Mentone (1887) (Later Kilbreda Girl's School)

- Auburn Hotel, Auburn (1888)

- St Kilda Coffee Palace, St Kilda

- Prince of Wales Coffee Palace

- Federal Coffee Palace. Corner of Collins and King Streets, Melbourne (1888) (demolished 1972)

- Garand Open House, Melbourne (demolished)

- Parer's Crystal Cafe. 103 Bourke Street, Melbourne (demolished)

- Burke & Wills Coffee Palace. Corner of Collins and Russell Streets, Melbourne (demolished)

- Queen's Coffee Palace. 1 Rathdowne Street, Carlton (demolished 1970)

- Hawthorn Coffee Palace, Hawthorn (demolished)

- Moris's (West Melbourne) Coffee Palace, West Melbourne (demolished)

- Sandringham House, Sandringham (demolished)

- James' Coffee Palace, Williamstown (demolished)

- Prahran Coffee Palace, Prahran, Victoria[4]

-

Hotel Windsor (formerly the Grand Coffee Palace)

-

Victoria Hotel – now private apartments

-

The George, St Kilda – now private apartments

-

Auburn Hotel

-

St Kilda Coffee Palace – now backpackers hostel

-

Mentone Coffee Palace – now Kilbreda Girl's School

-

Collingwood Coffee Palace in 1879

-

Melbourne Coffee Palace in 1882

-

Hawthorn Coffee Palace in 1887

-

Federal Coffee Palace in 1889

-

Queens Coffee Palace in 1889

Ballarat

- Reid's Coffee Palace (1886)

- Victoria Coffee Palace.[5] Cnr Lydiard and Doveton Crescent. Soldiers Hill. (demolished)

-

Reid's Coffee Palace, Ballarat

Bendigo

- Sandhurst Coffee Palace (demolished)

- Central Coffee Palace (demolished)

-

Sandhurst Coffee Palace in 1890

Queenscliff

- Palace (1879)

- Baillieu (1881) (later renamed Ozone Hotel)

- Vue Grande (1883)

- Queenscliff Hotel (1887)

-

Ozone, Queenscliff

-

Royal, Queenscliff

Other

- Mildura Coffee Palace, Mildura, Victoria

- Ozone Coffee Palace, Warrnambool

- Marnoo Coffee Palace, Marnoo, Victoria

- Wimmera Coffee Palace, Horsham, Victoria[6]

Tasmania

- Imperial (Hobart) Coffee Palace, Hobart, Tasmania (built in two sections, firstly in the 1880s then extended in 1910. Cast iron verandah, balcony and mansard roof were removed during the 1950s and the 1910 extension was demolished in the 1960s)

- Tasmanian Coffee Palace, Hobart, Tasmania, 89 Macquarie St (established in Ingle Hall which was built c1814). Also known as Norman's Coffee Palace, the Orient, and Anderson's. Now home to the Mercury Print Museum.

- Federal (Sutton's) Coffee Palace (later Metropole). Brisbane Street, Launceston, Tasmania (demolished 1976)

-

Launceston Coffee Palace, Brisbane Street

-

The Imperial, Hobart

South Australia

- Grayson's Coffee Palace, Adelaide, South Australia (demolished 1918)

- Coffee Palace, Hindley Street, Adelaide, South Australia (known as Grant's 1908-1919; Wests 1919-)

- Port Pioneer Coffee Palace. Hindley Street, Adelaide. (1879)[7]

New South Wales

- Sydney Coffee Palace, Sydney, New South Wales (founded 1879, rebuilt 1913-1914) (demolished ?)

- Sydney Coffee Palace, Woolloomooloo, New South Wales

- Grand Central Coffee Palace (1880), Sydney

- North Queensland Coffee Palace, George Street, Sydney

- Canberra Coffee Palace, Manly, New South Wales (built 1912, demolished 1955)

- Dorrigo Coffee Palace, [Hickory St, Dorrigo, New South Wales] (burnt down sometime after 1923)

- Bee Hive Coffee Palace, Sydney NSW

- Great Western Coffee Palace, Sydney NSW

- Town Hall Coffee Palace, Sydney NSW

- Johnsons Temperance Coffee Palace. York Street, Sydney. (built 1879)[8]

- Rose and Crown Coffee Palace. Knightsbridge, Sydney.[9]

- Alpine Heritage Motel (built as: Goulburn Coffee Palace) Goulburn, NSW

-

Grand Central Coffee Palace

Queensland

- People's Palace, Brisbane (built 1910-11, still standing 2010)[10]

- Royal George, Nambour, Queensland (built 1911, licenced in 1912 and destroyed by fire on 15 February 1961)

- Hill's Coffee Palace Dalby, Queensland

Western Australia

- Horseshoe Coffee Palace, Perth WA

- Worsleys Coffee Palace, Katanning, Perth WA

- 1904 Wise Directory has 20 coffee palaces listed in Perth and other locations in W.A>[11][12]

United Kingdom

- Douglas Coffee Palace, Douglas, Isle of Man (demolished 1930)[13]

- Newport Street Coffee Palace, Swindon

- Ossington Coffee Palace, Newark-on-Trent

See also

Bibliography

- Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion. Elaine Denby. Reaktion Books, 2002

References

- ↑ Grand Hotels: Reality and Illusion. Elaine Denby. Reaktion Books, 2002. p. 174

- ↑ Australian Town and Country Journal (NSW : 1870 - 1907) Saturday 13 September 1879 p 10 Article

- ↑ South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 - 1900) Saturday 25 September 1880 p 1 Advertising

- ↑ The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954) Saturday 24 January 1880 p 6 Article

- ↑ Ballarat: A Guide to Buildings and Areas, 1851-1940. Jacobs Lewis Vines Architects and Conservation Planners. 1981. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-9593970-0-0. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/72923577 Horsham Times, 9 April 1918 via Trove

- ↑ South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 - 1900) Saturday 14 June 1879 Supplement: Supplement to the South Australian Register. p 7 Advertising

- ↑ The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954) Monday 9 June 1879 p 2 Advertising

- ↑ The South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1858 - 1889) Friday 20 June 1879 p 4 Article

- ↑ "People's Palace (entry 14871)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council.

- ↑ http://www.slwa.wa.gov.au/find/guides/wa_history/post_office_directories/1904 pp.730-731 on 0396.pdf

- ↑ Brady, Wendy (1983) Serfs of the sodden scone: women workers in the West Australian hotel and catering industry, 1900-1925 - in Studies in Western Australian History number 7 (Women in Western Australian history), pp.33-45 - including work in coffee palaces

- ↑ http://www.douglas.gov.im/GalleryShowCat.asp?Cat=Streets&ID=46

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||