Cochinchina Campaign

| Cochinchina Campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Capture of Saigon by the French and Spanish expeditionary forces, by Antoine Léon Morel-Fatio. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Several dozen French and Spanish warships Around 3,000 French and Spanish regulars and colonial infantry by the end of the war 1 American sloop-of-war 50 American Sailors and Marines | 10,000+ infantry | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

236 killed 337 wounded | 471 killed | ||||||||

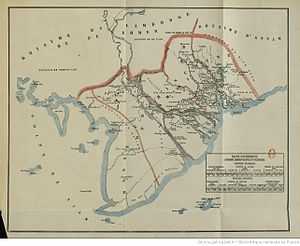

The Cochinchina campaign (French: Campagne de Cochinchine; Spanish: Expedición franco-española a Cochinchina; Vietnamese: Chiến dịch Nam Kỳ; 1858–1862), fought between the French and Spanish on one side and the Vietnamese on the other, began as a limited punitive campaign and ended as a French war of conquest. The war concluded with the establishment of the French colony of Cochinchina, a development that inaugurated nearly a century of French colonial dominance in Vietnam.

Background

The French had few pretexts to justify their imperial ambitions in Indochina. In the early years of the 19th century some Frenchmen believed that the Vietnamese emperor Gia Long owed the French a favour for the help French troops had given him in 1802 against his Tây Sơn enemies, but it soon became clear that the Gia Long felt no more bound to France than he did to China, which had also provided help. Gia Long felt that as the French government did not honour their agreement to assist him in the civil war—the Frenchmen who helped him were volunteers and adventurers not government units—he was not obliged to give them favours. Certainly, he and his successor Minh Mạng flirted with the French. Although the Vietnamese soon learned to reproduce the elaborate Vaubanesque fortresses that had been built at the end of the 18th century by French engineers, and no longer needed French technical assistance in the art of fortification, they were still interested in buying French cannon and rifles. But this limited contact with the French counted for little. Neither Gia Long nor Minh Mạng had any intention of coming under French influence.

But the French were not prepared to be brushed off quite so easily. As so often during the era of European colonial expansion, religious persecution created a reason for intervention. French missionaries had been active in Vietnam since the 17th century, and by the middle of the 19th century there were perhaps 300,000 Roman Catholic converts in Annam and Tonkin. Most of their bishops and priests were either French or Spanish. Most Vietnamese disliked and suspected this sizeable Christian community and its foreign leaders. The French, conversely, began to feel responsible for their safety. Harassment of the Christians eventually provided France with a respectable pretext for attacking Vietnam. The tension built up gradually. During the 1840s, persecution or harassment of Catholic missionaries in Vietnam by the Vietnamese emperors Minh Mạng and Thiệu Trị evoked only sporadic and unofficial French reprisals. The decisive step towards the establishment of a French colonial empire in Indochina was not taken until 1858.[1] In 1857, the Vietnamese emperor Tự Đức (r. 1848–83) executed two Spanish Catholic missionaries. This was neither the first nor the last such incident, and on previous occasions the French government had overlooked such provocations. But this time, Tự Đức's timing was inopportune, as it coincided with the Second Opium War. France and Britain had just despatched a joint military expedition to the Far East to chastise China, with the result that the French had troops on hand with which to intervene in Annam. In November 1857, Napoleon III of France authorised Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly to send a punitive expedition to Vietnam. In September 1858, a joint French and Spanish expedition landed at Tourane (Da Nang) and captured the town.[2]

Tourane and Saigon

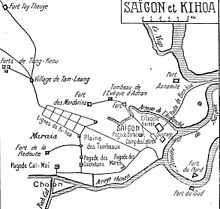

The allies expected an easy victory, but the war did not at first go as planned. The Vietnamese Christians did not rise in support of the French (as the missionaries had been confidently predicting they would), Vietnamese resistance was more stubborn than had been expected, and the French and Spanish found themselves besieged in Tourane by a Vietnamese army under the command of Nguyễn Tri Phương. The Siege of Tourane lasted for nearly three years, and although there was little fighting disease took a heavy toll of the allied expedition. The garrison of Tourane was reinforced from time to time, and occasionally mounted local attacks against the Vietnamese positions, but was unable to break the siege.[3] In October 1858, shortly after his capture of Tourane, Rigault de Genouilly cast around for somewhere else to strike the Vietnamese. Realising that the French garrison at Tourane was unlikely to achieve anything useful, he weighed up the possibility of action in either Tonkin or Cochinchina. He considered and rejected the possibility of an expedition to Tonkin, which would require a large-scale uprising by the Christians to have any chance of success, and in January 1859 proposed to the navy ministry an expedition against Saigon in Cochinchina, a city of considerable strategic significance as a source of food for the Vietnamese army. The expedition was approved, and in early February, leaving capitaine de vaisseau Thoyon at Tourane with a small French garrison and two gunboats, Rigault de Genouilly sailed south for Saigon. On 17 February 1859, after forcing the river defences and destroying a series of forts and stockades along the Saigon river, the French and Spanish captured Saigon. French marine infantry stormed the enormous Citadel of Saigon, while Filipino troops under Spanish command threw back a Vietnamese counterattack. The allies were not strong enough to hold the citadel, and on 8 March 1859 blew it up and set fire to its rice magazines. In April, Rigault de Genouilly returned to Tourane with the bulk of his forces to reinforce Thoyon's hard-pressed garrison, leaving capitaine de frégate Bernard Jauréguiberry (the future French navy minister) at Saigon with a Franco-Spanish garrison of around 1,000 men.[4]

The capture of Saigon proved to be as hollow a victory for the French and Spanish as their earlier capture of Tourane. Jauréguiberry's small force, which suffered substantial losses in a surprise attack on a Vietnamese fortification to the west of Saigon on 21 April 1859, was forced to remain behind its defences thereafter. Meanwhile, the French government was distracted from its Far Eastern ambitions by the outbreak of the Austro-Sardinian War, which tied down large numbers of French troops in Italy. In November 1859, Rigault de Genouilly was replaced by Admiral François Page, who was instructed to obtain a treaty protecting the Catholic faith in Vietnam but not to seek any territorial gains. Page opened negotiations on this basis in early November, but without result. The Vietnamese, aware of France's distraction in Italy, refused these moderate terms and spun out the negotiations in the hope that the allies would cut their losses and abandon the campaign altogether. On 18 November 1859 Page bombarded and captured the Kien Chan forts at Tourane, but this allied tactical victory failed to change the stance of the Vietnamese negotiators. The war continued into 1860.[5] During the second half of 1859 and throughout 1860, the French were unable to substantially reinforce the garrisons of Tourane and Saigon. Although the Austro-Sardinian War soon ended, by early 1860 the French were again at war with China, and Page had to divert most of his forces to support Admiral Léonard Charner's China expedition. In April 1860, Page left Cochinchina to join Charner at Canton. Meanwhile, in March 1860, a Vietnamese army around 4,000 strong began to besiege Saigon. The defence of Saigon was entrusted to capitaine de vaisseau d'Ariès. The Franco-Spanish force in Saigon, only 1,000 men strong, had to support a siege by greatly superior numbers from March 1860 to February 1861. Realising that they could not hold both Saigon and Tourane, the French evacuated the garrison of Tourane in March 1860, bringing the Siege of Tourane to an inglorious end.[6]

Ky Hoa and Mỹ Tho

Although the French had evacuated Tourane, they successfully held out in Saigon for the remainder of 1860. But they were not strong enough to break the Vietnamese siege of Saigon. The military stalemate was only broken in early 1861, as a result of the ending of the war with China. Admirals Charner and Page were now free to return to Cochinchina and resume the campaign around Saigon. A naval armada of 70 ships under Charner's command and 3,500 soldiers under the command of General de Vassoigne were transferred from northern China to Saigon. Charner's squadron, the most powerful French naval force seen in Vietnamese waters before the creation of the French Far East Squadron on the eve of the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885), included the steam frigates Impératrice Eugénie and Renommée (Charner and Page's respective flagships), the corvettes Primauguet, Laplace and Du Chayla, eleven screw-driven despatch vessels, five first-class gunboats, seventeen transports and a hospital ship. The squadron was accompanied by half a dozen armed lorchas purchased in Macao.[7] With this powerful reinforcement, the allies eventually began to gain the upper hand. On 24 and 25 February 1861, the French and Spanish in Saigon successfully assaulted the Vietnamese siege lines, defeating marshal Nguyễn Tri Phương's besieging Vietnamese army in the battle of Ky Hoa. The Vietnamese fought bitterly to defend their positions, and allied casualties were considerable.[8]

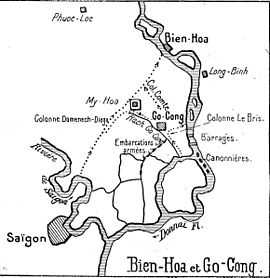

The victory at Ky Hoa allowed the French and Spanish to move to the offensive. In April 1861, Mỹ Tho fell to the French. An assault force under the command of capitaine de vaisseau Le Couriault du Quilio, supported by a small flotilla of gunboats, advanced on Mỹ Tho from the north along the Bao Dinh Ha creek, and between 1 and 11 April destroyed several Vietnamese forts and fought its way along the creek to the environs of Mỹ Tho. Le Couriault de Quilio gave orders for an assault on the town on 12 April, but in the event the assault was not necessary. A flotilla of warships under the command of Admiral Page, who had been sent by Charner to sail up the Mekong River to attack Mỹ Tho by sea, appeared off the town on the same day. Mỹ Tho was occupied by the French on 12 April 1861 without a shot being fired.[9] In March 1861, shortly before the capture of Mỹ Tho, the French again offered terms to Tự Đức. This time the terms were considerably harsher than those offered by Page in November 1859. The French demanded the free exercise of Christianity in Vietnam, the cession of Saigon province, an indemnity of 4 million piastres, freedom of commerce and movement inside Vietnam and the establishment of French consulates. Tự Đức was only prepared to concede on the free exercise of religion, and rejected the other French terms. The war went on, and after the fall of Mỹ Tho the French raised their territorial claims to include Mỹ Tho province as well as Saigon province.[10] Unable to confront the French and Spanish forces in battle, Tự Đức resorted to guerilla warfare, sending his agents into the conquered Vietnamese provinces to organise resistance to the invaders. Charner responded on 19 May by declaring Saigon and Mỹ Tho provinces to be in a state of siege. French columns roved through the Cochinchinese countryside, fanning popular resistance by the brutality with which they treated suspected insurgents. Charner had ordered them not to offer violence to peaceful villagers, but these orders were not always obeyed. The Vietnamese guerillas on occasion posed a serious threat to the French. On 22 June 1861 the French post at Gò Công was attacked, unsuccessfully, by 600 Vietnamese insurgents.[11]

Qui Nhon

The Bombardment of Qui Nhon, was an attack by a United States Navy warship upon a Vietnamese held fort protecting Qui Nhon in Cochinchina. United States forces under James F. Schenck went to Cochinchina to search for missing American citizens but were met with cannon fire upon arriving. In response to the attack the American warship bombarded the fort until it was reduced. The incident occurred during French and Spanish conquest of the nation.

Commander John Schenck was serving with the East India Squadron in June 1861 just before setting sail east to join the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. His last mission in the Far East was to proceed with the paddle steamer sloop USS Saginaw to Qui Nhon. A boat filled with sailors from the American merchant ship Myrtle was reported missing so Flag Officer Frederick K. Engle ordered Schenck to search the area. The Saginaw was armed with one 50-pounder (23 kg), one 32-pounder (15 kg) and two 24-pound rifled guns. She had a complement of fifty officers and enlisted men. Commander Schenck arrived off Qui Nhon of July 30 and prepared to enter the harbor the following day at 1:00 am. He wanted to ask the Vietnamese if they had seen the missing sailors. When the Saginaw was entering the harbor of Qui Nhon on July 31, the nearby fort to the north, mounting a few guns, opened fire at a range of 600 yards.

USS Saginaw 's crew was just putting the anchor down when the first shot burst in the water next to the ship. Surprised, the Americans first raised a white flag to show their friendly intentions but then a second shot was fired along with a third. Trying to get up steam, the Saginaw turned around and withdrew slowly to 900 yards, by which time her crew were at station and ready for action. The American gunners returned fire with one of their 32-pounders and after only about twenty minutes the Vietnamese guns were silenced. A secondary explosion was observed and it was suspected that either the powder magazine of the fort, or one of the guns, blew up and killed their operators. After the explosion no further shots were fired from the fort. However, the Saginaw 's gunners continued their bombardment for another half hour unopposed until the fort was in ruins. American forces suffered no damage or casualties and after the action, communicating with the natives proved fruitless so the Saginaw steamed back to Hong Kong.

The men of Saginaw ultimately did not find the missing American sailors but they did engage in an unprovoked gunnery duel which ended with a clear victory. Commander Schenck went on the serve with distinction at the battles for Fort Fisher during the American Civil War.

Bien Hoa and Vĩnh Long

The Capture of Mỹ Tho was Charner's last military success. He returned to France in the summer of 1861, and was replaced in command of the Cochinchina expedition by Admiral Louis-Adolphe Bonard (1805–67), who arrived in Saigon at the end of November 1861. A mere fortnight after his arrival in Saigon, in reprisal for the loss of the French lorcha Espérance and all her crew in an ambush, Bonard mounted a major campaign to overrun Đồng Nai Province. Biên Hòa, the provincial capital, was captured by the French on 16 December 1861.[12] The French followed up their victory at Biên Hòa by capturing Vĩnh Long on 22 March 1862, in a brief campaign mounted by Admiral Bonard in reprisal for Vietnamese guerilla attacks on French troops around Mỹ Tho. In the most serious of these incidents, on 10 March 1862, a French gunboat leaving Mỹ Tho with a company of infantry aboard suddenly exploded. Casualties were heavy (52 men killed or wounded), and the French were convinced that the gunboat had been sabotaged by insurgents directed by the governors of Vĩnh Long Province.[13] Ten days later, Bonard anchored off Vĩnh Long with a flotilla of eleven despatch vessels and gunboats and a Franco-Spanish landing force of 1,000 troops. In the afternoon and evening of 22 March, the French and Spanish assaulted the Vietnamese batteries entrenched before Vĩnh Long and captured them. On 23 March they entered the citadel of Vĩnh Long. Its defenders retreated to a fortified earthwork at My Cui, 20 kilometres to the west of Mỹ Tho, but two allied columns pursued them and drove them from My Cui while a third cut off their retreat northwards. Vietnamese casualties at Vĩnh Long and My Cui were heavy.[14]

The fall of Vĩnh Long, coming after the loss of Mỹ Tho and Bien Hoa, disheartened the Court of Huế, and in April 1862 Tự Đức let it be known that he was willing to make peace.[15] In May 1862, following preliminary discussions at Huế, the French corvette Forbin sailed to Tourane to receive Vietnamese plenipotentiaries charged with concluding peace. The Vietnamese were given three days to produce their ambassadors. The sequel was described by Colonel Thomazi, the historian of the French conquest of Indochina:

On the third day, an old paddlewheel corvette, the Aigle des Mers, was seen slowly leaving the Tourane river. Her beflagged keel was in a state of dilapidation that excited the laughter of our sailors. It was obvious that she had not gone to sea for many years. Her cannons were rusty, her crew in rags, and she was towed by forty oared junks and escorted by a crowd of light barges. She carried the plenipotentiaries of Tự Đức. Forbin took her under tow and brought her to Saigon, where the negotiations were briskly concluded. On 5 June a treaty was signed aboard the vessel Duperré, moored before Saigon.[16]

The peace

By then the French were not in a merciful mood. What had begun as a minor punitive expedition had turned into a long, bitter and costly war. It was unthinkable that France should emerge from this struggle empty-handed. Tự Đức's minister Phan Thanh Giản signed a treaty with Admiral Bonard and the Spanish representative Colonel Palanca y Gutierrez on 5 June 1862. The Treaty of Saigon required Vietnam to permit the Catholic faith to be preached and practised freely within its territory; to cede the provinces of Biên Hòa, Gia Định and Định Tường and the island of Poulo Condore to France; to allow the French to trade and travel freely along the Mekong River; to open Tourane, Quảng Yên and Ba Lac (at the mouth of the Red River) as trading ports; and to pay an indemnity of a million dollars to France and Spain over a ten-year period. The French placed the three southern Vietnamese provinces under the control of the navy ministry. Thus, casually, was born the French colony of Cochinchina, with its capital at Saigon.[17]

Aftermath

In 1864 the three southern provinces ceded to France were formally constituted as the French colony of Cochinchina. Within three years, France's new colony doubled in size. In 1867 Admiral Pierre de la Grandière forced the Vietnamese to cede the provinces of Châu Đốc, Hà Tiên and Vĩnh Long to France. The Vietnamese emperor Tự Đức initially refused to accept the validity of this cession, but eventually recognized French dominion over the six provinces of Cochinchina in the 1874 Treaty of Saigon, negotiated by Paul-Louis-Félix Philastre after the military intervention of Francis Garnier in Tonkin.[18] The Spanish, who had played a junior role in the Cochinchina campaign, received a share of the indemnity but made no territorial acquisitions in Vietnam. Instead, they were encouraged by the French to seek a sphere of influence in Tonkin. Nothing came of this suggestion, however, and Tonkin ultimately fell under French control also, becoming a French protectorate in 1883.[19] Perhaps the most important factor in Tự Đức's decision to make peace was the threat posed to his authority by a serious uprising in Tonkin led by the Catholic nobleman Le Bao Phung, who claimed descent from the old Lê Dynasty. Although the French and Spanish rejected Le's offer of an alliance against Tự Đức, the insurgents in Tonkin were able to inflict several defeats on Vietnamese government forces. The end of the war with France and Spain allowed Tự Đức to overwhelm the insurgents in Tonkin and restore government control there. Le Bao Phung was eventually captured, tortured and put to death.[20]

Notes

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 25–9

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 29–33

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 38–41

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 33–7

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 40; Histoire militaire, 27

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 37–43

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 45

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 29–31

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 32–3

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 60–61

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 61

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 63–5

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 67-8; Histoire militaire, 35

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 68–9; Histoire militaire, 35–6

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 69–71

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 70

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 69–71

- ↑ Brecher, 179

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 46–7

- ↑ McAleavy, 76–7; Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 36 and 37

References

- Brecher, M., A Study of Crisis (University of Michigan, 1997)

- McAleavy, H., Black Flags in Vietnam: The Story of a Chinese Intervention (New York, 1968)

- Taboulet, G., La geste française en Indochine (Paris, 1956)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine français (Hanoi, 1931)

- Bernard, H., Amiral Henri Rieunier, ministre de la marine - La vie extraordinaire d'un grand marin, 1833-1918 (Biarritz, 2005)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||