Clint Eastwood in the 1970s

| |

This article is part of a series on Clint Eastwood |

|---|---|

In the 1970s, Clint Eastwood's acting career was at its peak.

Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970)

In 1970, Eastwood starred in the western, Two Mules for Sister Sara with Shirley MacLaine. The film, directed by Siegel, is a story about an American mercenary who gets mixed up with a prostitute disguised as a nun and aid a group of Juarista rebels during the puppet reign of Emperor Maximilian in Mexico.[1][2] The story was initially written by Budd Boetticher, who was later sacked and replaced with Albert Maltz to revise the script.[3] The film saw Eastwood embody the tall mysterious stranger once more, unshaven, wearing a serape-like vest and smoking a cigar and the film score was composed by Morricone.[4] Although the film had Leonesque dirty Hispanic villains, the film was considerably less crude and more sardonic than those of Leone.[5] The role of Sister Sara was initially offered to Elizabeth Taylor during the filming of Where Eagles Dare (Taylor then being the wife of Richard Burton) but Taylor had to turn down the role because she wanted to shoot in Spain where Burton was filming his latest movie.[5] Although Sister Sara was supposed to be Mexican, they eventually cast Shirley MacLaine although they were initially unconvinced with her pale complexion.[6] Both Siegel and Eastwood felt intimidated by her on set, and Siegel described Clint's co-star as, "It's hard to feel any great warmth to her. She's too unfeminine and has too much balls. She's very, very hard."[7] Two Mules for Sister Sara marked the last time that Eastwood would receive second billing for a film and it would be 25 years until he risked being overshadowed by a leading lady again in The Bridges of Madison County (1995).

The film, which took four months to shoot and cost around $4 million to make,[8] received moderate reviews, and Roger Greenspun of the New York Times reported, "I'm not sure it is a great movie, but it is very good and it stays and grows on the mind the way only movies of exceptional narrative intelligence do".[7]Stanley Kauffman described the film as "an attempt to keep old Hollywood alive- a place where nuns can turn out to be disguised whores, where heroes can always have a stick of dynamite under their vests, where every story has not one but two cute finishes. Its kind of The African Queen gone west".[9][10]The New York Times in its book, The New York Times Guide to the Best 1000 Movies Ever Made included Two Mules for Sister Sara in its top 1000 films of all time.[11]

Kelly's Heroes (1970)

Later in 1970 he appeared in the World War II movie, Kelly's Heroes with Donald Sutherland and Telly Savalas. The film, which stars Eastwood as one of a group of Americans who steal a fortune in bullion from the Nazis, combined tough-guy action with offbeat humor. It was the last non-Malpaso film that Clint agreed to appear in.[12] The filming commenced in July 1969 and was shot on location in Yugoslavia and London.[8] Directed by Brian G. Hutton, the film involved hundreds of extras and dangerous special effects. The climax to the film echoes that of his Dollars films when he advances in lockstep on a German Tiger tank on the street of a small European town, with a Morricone-esque soundtrack by Lalo Schifrin.[8] The film received mostly a positive reception and its anti-war sentiments were recognized.[12] The film has a respectable 83% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[13]

The Beguiled (1971)

In the winter of 1969-70, Eastwood and Siegel began planning his next film, The Beguiled. Jennings Lang was inspired by the 1966 novel by Thomas P. Cullinan and in passing the book to Eastwood he was engrossed throughout the night in reading the tale of a wounded Union soldier held captive by the sexually repressed matron of a southern girls' school.[14] This was the first of several films where Eastwood has agreed to storylines where he is the centre of female attention, including minors.[14] Albert Maltz, who had worked on Two Mules for Sister Sara was brought in to draft the script, but disagreements in the end led to a revision of the script by Claude Traverse, who although uncredited, led to Maltz being credited under a pseudonym.[15] The film, according to Siegel, deals with the themes of sex, violence and vengeance and addressed "the basic desire of women to castrate men".[16] Jeanne Moreau was considered for the role of the domineering headmistress Martha Farnsworth, but in the end the role went to acclaimed Broadway actress Geraldine Page, and actresses Elizabeth Hartman, Jo Ann Harris, Darlene Carr, Mae Mercer and Pamelyn Ferdin were cast in supporting roles. The film received major recognition in France, and was proposed by Pierre Rissient to the Cannes Film Festival, and while agreed to by Eastwood and Siegel, the producers declined.[17] It would be widely screened in France later and is considered one of Eastwood's finest works by the French.[18] Although the film reached number two on Variety's chart of top grossing films, it was poorly marketed and in the end grossed less than $1 million, earning over four times less than Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song did at the same time and falling to below 50 in the charts within two weeks of release.[17] According to Eastwood and Jennings Lang, the film, aside from being poorly publicized, flopped due to Clint being "emasculated in the film".[17] Eastwood said of his role in The Beguiled:

"Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino play losers very well. But my audience like to be in there vicariously with a winner. That isn't always popular with critics. My characters have sensitivity and vulnerabilities, but they're still winners. I don't pretend to understand losers. When I read a script about a loser I think of people in life who are losers and they seem to want it that way. It's a compulsive philosophy with them. Winners tell themselves, I'm as bright as the next person. I can do it. Nothing can stop me."[17]

On July 21, 1970, Eastwood's father died of a heart attack, unexpectedly at the age of 64.[19] It came as a shock to Eastwood as his grandfather had lived to 92 and had a profound impact on Eastwood's life, described by Fritz Manes as "the only bad thing that ever happened to him in his life". After this, Eastwood had a greater sense of urgency on set and retains this speed and efficiency onset to this day.[20] He became increasingly concerned with health and fitness after his father's death, refusing to drink hard liquor (although he still regularly drank cold beer and opened a pub, The Hog's Breath Inn in Carmel in 1971[21]) and adopting a rigorous health regime.[20]

Play Misty for Me (1971)

1971 proved to be a professional turning point in Eastwood's career.[22] Before Irving Leonard had died, the last film they had discussed at Malpaso was to give Eastwood the artistic control that he desired and make his directorial debut in Play Misty for Me.[19] The script was originally thought of by Jo Heims, a former model and dancer turned secretary and was polished off by Dean Riesner.[19] Heim's story involves a jazz disc jockey named Dave (Eastwood) who has a casual affair with Evelyn (Jessica Walter), one of his listeners who had been calling the radio station repeatedly at night asking him to play her favourite song, Erroll Garner's Misty. When Dave ends their relationship the female fan becomes possessive and then violent, turning into a crazed murderess.[20] The idea of another lover's interest with a level-headed girlfriend Tobie added to the plot was a suggestion by Sonia Chernus, an editor who had originally been there when Eastwood initially was spotted for Rawhide.[20] The storyline was originally set in Los Angeles, but under Eastwood's insistence, the film was shot in the more comfortable surroundings of the Carmel area, where he could shoot scenes at the local radio station, bars and restaurants and at friends' houses.[20] Filming commenced in Monterey in September 1970 and although this was Eastwood's debut, Siegel stood by and frequent collaborators of Siegel's, such as cinematographer Bruce Surtees, editor Carl Pingitore and composer Dee Barton, made up part of the filming team.[23] The rights to the song Misty were obtained after Eastwood saw Garner at the [[<ref>Concord Summer Festival</ref>]] in 1970 and he later paid $2,000 for the use of the song The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face by Roberta Flack.[23]

"I will never win an Oscar and do you know why? First of all, because I'm not Jewish. Secondly, because I make too much money for those old farts in the Academy. Thirdly, and most importantly, because I don't give a fuck"

Meticulous planning and efficient directorship by Eastwood saw the film fall nearly $50,000 short of its $1 million budget and the film was completed four or five days ahead of schedule.[23] Rissient successfully arranged for Play Misty for Me to premiere in October 1971 and for it to premiere at the San Francisco Film Festival and was widely released in the November.[25] The film was highly acclaimed by critics, with critics such as Jay Cocks in Time, Andrew Sarris in the Village Voice and Archer Winsten in the New York Post all praising Eastwood's directorial skills and the film, including his performance in the scenes with Walter.[25]

Dirty Harry (1971)

The script to Dirty Harry was originally written by Harry Julian and Rita M. Fink, a story about a hard-edged New York City police inspector Harry Callahan, determined to stop a psychotic killer by any means at his disposal.[26] The script was presented to Eastwood by Jennings Lang and the rights to the film were bought by Warner Brothers. Irvin Kershner was originally intended as director as was Frank Sinatra to play the character but he had reportedly grown unhappy with the script, although withdrew officially because of a hand injury.[26] While Play Misty for Me was attractive to Eastwood, "by the sadness of the character", he signed up for Dirty Harry and this was reported in the press in December 1970 that Malpaso would be producing the film in a joint venture with Warner Brothers.[27] Many locations in the script were altered and moved to San Francisco. One evening Eastwood and Siegel had been watching the San Francisco 49ers in the Kezar Stadium in the last game of the season and thought the eerie Greek amphitheatre like setting would be an excellent location for shooting one of the scenes where Callahan encounters the psychopathic killer Scorpio.[27]

A railway trestle crossing over Sir Francis Drake Boulevard would be used in the finale. Andy Robinson, whom Eastwood had seen in a play called Subject to Fits, was cast as the killer Scorpio, whose unkempt appearance fit the bill for a mentally ill hippie.[28] Past collaborators Surtees, Pingitore and Schifrin were once again hired, with Schifrin composing many of the jazz tracks to the film. Glenn Wright, Eastwood's costume designer since Rawhide was responsible for creating Callahan's distinctive old-fashioned brown and yellow checked jacket to emphasise his strong values in pursuing crime.[28] Filming for Dirty Harry began in April 1971 and involved some risky stunts, with much footage shot at night and filming the city of San Francisco aerially which the film series is renowned for.[28] Dirty Harry is arguably Eastwood's most memorable character and the lines that Callahan utters when addressing a wounded bank robber are often cited amongst the most memorable in cinematic history (see box).

"I know what you're thinking — 'Did he fire six shots or only five?' Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I've kinda lost track myself. But, being as this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you've got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?"

The film has been cited with inventing the "loose-cannon cop genre" that is imitated to this day. Eastwood's tough, no-nonsense portrayal of Dirty Harry touched a cultural nerve with many who were fed up with crime in the streets. The film was released at a time (1970–71) when there were prevalent reports of local and federal police committing atrocities and overstepping their authority by entrapment and obstruction of justice.[29] Americans needed a hero, a winner at a time when the authorities were losing the battle against crime.[29] After release in December 1971, Dirty Harry proved a phenomenal success which would be go on to become Siegel's highest grossing film and the start of a series of films which is arguably Eastwood's signature role, with fans demanding more. Although some critics, including Jay Cocks of Time, praised his performance as Dirty Harry, describing him as "giving his best performance so far, tense, tough, full of implicit identification with his character",[30] the film was widely criticized because of Eastwood's portrayal of the ruthless cop. Feminists in particular were outraged by the film, and at the 1971 Oscar telecast, protested outside holding up banners which read messages such as "Dirty Harry is a Rotten Pig".[31] Many critics expressed concern with what they saw as bigotry, with Newsweek describing the film as "a right-wing fantasy", Variety as "a specious, phony glorification of the police and police brutality with a superhero whose antics become almost satire" and a raging review by Pauline Kael of The New Yorker who accused Eastwood of a "single-minded attack against liberal values".[31] Several people accused him of racism in the decision to cast four African-Americans as the bank robbers.[32] Eastwood dismissed the political outrage, claiming that Callahan was just obeying a higher moral authority, and said, "some people are so politically oriented, when they see cornflakes in a bowl, they get some complex interpretation out of it."[32]

Joe Kidd (1972)

Around this time, Eastwood was offered the role of James Bond following the departure of Sean Connery, but turned it down due to his belief that the character should be played by an English actor.[33] Eastwood next starred in the loner Western Joe Kidd, released in 1972. He was given the script by Jennings Lang, written by novelist Elmore Leonard. Originally called The Sinola Courthouse Raid, it was about a character inspired by Reies Lopez Tijerina, an ardent supporter of Robert F. Kennedy, known for storming a courthouse in Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico in an incident in June 1967, taking hostages and demanding that the Hispanic people be granted their ancestral lands back to them. Leonard depicted Tijerina in his story, a man he named Luis Chama, as an egomaniac, a role which went to actor John Saxon. Robert Duvall was cast as Frank Harlan, a ruthless land owner who hires Eastwood's character, a former frontier guide named Joe Kidd, to track down the culprits and scare them away. Don Stroud, who Eastwood had starred alongside in Coogan's Bluff, was cast as another sour villain who encounters Joe Kidd. Under the director's helm of John Sturges, who had directed acclaimed westerns such as The Magnificent Seven (1960), filming began in Old Tucson in November 1971, overlapping with another film production, John Huston's The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, which was just wrapping up shooting.[34] Outdoor sequences to the film were shot near June Lake, east of the Yosemite National Park.[34]

The actors were initially uncertain with the strength of the three main characters in the film and how the hero Joe Kidd would come across.[35]

"I think it is a very good performance in context. Like so many Western heroes, Joe Kidd figures even in his own time as an anachronism — powerful through his instincts mainly, and through the ability of everybody else, whether in rage or gratitude, to recognize in him a quality that must be called virtue. The great value of Clint Eastwood in such a position is that he guards his virtue very cannily, and in the society of "Joe Kidd", where the men still manage to tip their hats to the ladies, but just barely, all the Eastwood effects and mannerisms suggest a carefully preserved authenticity."

According to writer Leonard, the initial slow development between the three was probably because the cast were so initially awestruck by having Sturges direct that they surrendered authority to him.[35] Eastwood was far from in perfect health during the film and suffered symptoms that relayed the possibility of a bronchial infection and suffered several panic attacks, falsely reported in the media as him having an allergy to horses.[37] During production, the script for the finale was altered when producer Bob Daley jokingly said that a train should crash through the barroom in the climax and he was taken seriously by cast and crew and they thought it was a great idea.[34] Joe Kidd received a mixed reception. For instance Roger Greenspunof The New York Times thought the film overall was nothing remarkable and had foolish symbolism and what he suspected was sloppy editing, but praised Eastwood's performance (see box).

Eastwood had now starred in an astonishing ten films in a four-year period and a headline published in the Motion Picture Herald in 1972 read, 'Eastwood Topples John Wayne', who only had one release that year; The Cowboys.[38]

High Plains Drifter (1973)

1973 proved another benchmark to Eastwood when he directed his first western, High Plains Drifter. Under a joint production between Malpaso and Universal, the script was created by Ernest Tidyman, an acclaimed writer who had won an Oscar for Best Screenplay for The French Connection.[38] Dean Riesner collaborated and came up with the final plot; a tall, mysterious stranger arrives in a brooding Western town where the people share a guilty secret. They hire the stranger to defend the town against three felons soon to be released but fail to recognise that they once killed this stranger in a brutal whipping and that his reappearance is supernatural. The ghostly stranger forces the people to paint the town red and names it "Hell" and seeks revenge. Holes in the plot were filled in with black humor and allegory, influenced by Sergio Leone.[38] Henry Bumstead was brought in the design the eerie set, set on the shores of Mono Lake, Bruce Sartees as the cinematographer and Dee Barton composing the equally eerie score which ranged from typical Morricone type grandeur to horror-esque shrilling. High Plains Drifter would be the first of six movies Eastwood made with friend Geoffrey Lewis. The revisionist film received a mixed reception from critics but was a major box office success. A number of critics thought Eastwood's directing was as a derivative as it was expressive with Arthur Knight in Saturday Review remarking that Clint had "absorbed the approaches of Siegel and Leone and fused them with his own paranoid vision of society".[39] Jon Landau of Rolling Stone concurred, remarking that it is his thematic shallowness and verbal archness which is where the film fell apart, yet he expressed approval of the dramatic scenery and cinematography.[39]

Breezy (1973) (director only)

Elmore Leonard had proposed the idea of a film about an artichoke farmer who refused to surrender to a criminal syndicate trying to squeeze his profits. Eastwood had read the twenty five pages outlined by Leonard and refused the offer, despite him setting the film around Castroville, near Carmel.[40] Instead, Eastwood turned his attention towards a script written by Jo Heims about a love blossoming between a middle-aged man and a teenage girl, Breezy. Heims had originally intended Clint to play the starring role of the realtor Frank Harmon, a bitter divorced man who falls in love with the young Breezy. Whilst Eastwood confessed to "understanding the Frank Harmon character" he believed he was too young at that stage to play Harmon.[41] That part would go to William Holden, twelve years Eastwood's senior and Clint decided to direct the picture. During casting for the film, Eastwood met Sondra Locke for the first time, an actress who would play a major role in many of his films for the next ten years and an important figure in his life.[41] Locke, who was 26 at this time, was considered too old for the Breezy part and after much auditioning, a young dark-haired actress named Kay Lenz, who had recently appeared in American Graffiti, was cast. According to friends of Clint, he became infatuated with Lenz during this period.[42] Filming for Breezy began in the November of 1972 in Los Angeles. With Surtees occupied elsewhere, Frank Stanley was brought in the shoot the picture, the first of four films he would shoot for Malpaso.[42] The film was shot very quickly and efficiently and in the end went $1 million under budget and finished three days before schedule.[42] The film was not a major success, it barely reached the Top 50 before disappearing and was only made available on video in 1998.[43] Nor was it received particularly well by critics. Some critics, including Eastwood's biographer Richard Schnickel believed that the sexual content of the film and love scenes were too soft to be memorable for such a potentially scandalous relationship between Harmon and Breezy, commenting that, "it is not a sexy movie. Once again, Eastwood was too polite in his eroticism."[43]

Magnum Force (1973)

After the filming of Breezy had finished, Warner Brothers announced that Eastwood had agreed to reprise his role as Detective Harry Callahan in a sequel to Dirty Harry, running under the title, Vigilance. Writer John Milius came up with a storyline in which a group of rogue young officers in the San Francisco Police Force systematically exterminate the city's worst criminals, portraying the idea that there are worse cops than Dirty Harry.[44] David Soul, Tim Matheson, Robert Urich and Kip Niven were cast as the young vigilante cops.[45] Milius was a gun aficionado and political conservative and the film would extensively feature gun shooting in practice, competition and on the job.[45] Given this strong theme in the film, the title was soon changed to Magnum Force in deference to the .44 Magnum that Harry liked to use. Milius thought it was important to remind the audiences of the original film by incorporating the line "Do ya feel lucky?", repeated in the opening credits and with Dirty Harry once again eating a hot dog but this time foiling an airplane hijacking at the airport.[45] With Milius committed to filming Dillinger, Michael Cimino was later hired to revise the script, overlooked by Ted Post, who was to direct. Frank Stanley was hired as cinematographer and Lalo Schifrin once again conducted the score and filming commenced in late April 1973.[45] During filming Eastwood encountered numerous disputes with Post over who was calling the shots in directing the film, and Eastwood failed to authorize two important scenes directed by Post in the film because of time and expenses, one of them was at the climax to the film with a long shot of Eastwood on his motorcycle and he confronts the rogue cops.[46] Eastwood was intent, like with many of his films on shooting it as smoothly as possible, often refusing to do retakes over certain scenes insisted on by Post who later remarked, "A lot of the things he said were based on pure, selfish ignorance, and showed that he was the man who controlled the power. By Magnum Force Clint's ego began applying for statehood".[46] Post remained bitter with Eastwood for many years and claims disagreements over the filming affected his career afterwards.[47] According to director of photography Rexford Metz, "Eastwood would not take the time to perfect a situation. If you've got seventy percent of a shot worked out, that's sufficient for him, because he knows his audience will accept it."[46] Although the film was a major success after release, grossing $58.1 million in the U.S. alone, a new record for Eastwood, it was not a critical success. New York Times critics such as Nora Sayre criticized the often contradictory moral themes of the film and Frank Rich believed it "was the same old stuff".[47]Pauline Kael, a harsh critic of Eastwood for many years mocked his performance as Dirty Harry, commenting that, "He isn't an actor, so one could hardly call him a bad actor. He'd have to do something before we could consider him bad at it. And acting isn't required of him in Magnum Force.[47]

Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)

In 1973, Eastwood teamed with Jeff Bridges in the buddy action caper Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. The idea for the film was originally devised by Stan Kamen of the William Morris Agency, but was written by Michael Cimino who had previously written for Magnum Force, the previous year and would direct the picture.[48] The film is a road movie about a Korean War veteran turned bank robber Thunderbolt (Eastwood) who teams with a young con man drifter, Lightfoot (Bridges) who try to stay ahead of the vengeful ex-members of his gang (George Kennedy and Geoffrey Lewis) in the search for a cash deposit abandoned from an old heist. Given that for Eastwood this was an offbeat film, Franks Wells of Warner Brothers refused to back Malpaso in the production, leaving him to turn to United Artists and producer Bob Daley.[49] Frank Stanley was brought in as photographer with Dee Barton scoring the film as he had previously done on many of Clint's films. Although Eastwood generally refused to spend much time in scouting for locations, particularly unfamiliar ones, Cimino and Daley travelled extensively around the Big Sky Country in Montana for thousands of miles and eventually decided on the Great Falls area and to shoot the film in the towns of Ulm, Hobson, Fort Benton, Augusta and Choteau and surrounding mountainous countryside.[49] Filming for Thunderbolt and Lightfoot was shot between July and September 1973 and unusually for an Eastwood film, Cimino took a high number of retakes of scenes to perfect it.[49] On release in spring 1974, the film was praised for its offbeat comedy mixed with high suspense and tragedy and Eastwood's acting performance was noted by critics to the extent that Clint himself believed it was Oscar worthy.[50] Many critics widely believed that he was overshadowed by Jeff Bridges who stole the show in his performance as Lightfoot, and when he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, Eastwood was reportedly fuming at his own lack of Academy Award recognition.[50] Despite critical acclaim, the film was only a modest success at the box office, earning $32.4 million.[51] Eastwood was unhappy with the way that United Artists had produced the film and swore "he would never work for United Artists again", and the scheduled two film deal between Malpaso and UA was cancelled.[51]

The Eiger Sanction (1975)

The Eiger Sanction was based on a critically acclaimed spy novel by Trevanian. The rights to the film were bought by Universal as early as 1972, soon after the book was published, and was originally a Richard Zanuck and David Brown production.[51] Paul Newman was intended to the role of Jonathan Hemlock (Eastwood), an assassin turned college art professor who decides to return to his former profession for one last sanction in return for a rare Picasso painting; he must climb the Eiger face in Switzerland and perform the deed under perilous conditions. After reading the script, Newman declined, because he believed the film was too violent.[51] With initial concerns over early scripts, in February 1974, Eastwood contacted novelist Warren Murphy (known for his The Destroyer assassin series) in Connecticut asking for assistance despite him having never read the book or having ever written for a film before.[52] Murphy read the novel and agreed to write the script but was not happy with the tone of the novel which he believed was patronizing to its readers.[52] A first draft created by Murphy emerged in late March and a revised script was completed a month later.[53] George Kennedy, who had recently finished filming Thunderbolt and Lightfoot with Eastwood was cast as Big Ben Bowman, Hemlock's friend and secret adversary, Jack Cassidy cast as the Miles Mellough, and Thayer David as "Dragon," Hemlock's albinistic ex-Nazi boss, who is confined to semi-darkness and kept alive by blood transfusions. After a trip to Las Vegas, Vonetta McGee of Thomasine and Bushrod was cast as the African-American female spy Jemima Brown.[54]

Mike Hoover, an Academy Award nominated professional mountaineer from Jackson, Wyoming was hired to serve as a mountaineering cinematographer and technical adviser during the shoot. He taught Eastwood how to climb over some weeks of preparation in the summer of 1974 in Yosemite, and filming commenced in Grindelwald, Switzerland on August 12, 1974 with an extensive team of professional climbing experts and advisers on board from America, England, Germany, Switzerland and Canada.[54] The team were based at the Kleine Schneidegg Hotel for the entirety of the shoot.[55] Although the Eiger is lower than many other mountains at 13,041 feet, it is documented for its treacherous climbing and means "ogre" in German and has earned its nickname "mörderwall" in German, literally meaning "killer wall".[55] The decision by Eastwood to brave the mountain was strongly disapproved by Dougal Haston, the director of the International School of Mountaineering who warned him of the dangers and that he had lost climbers on the Eiger and even by cameraman Frank Stanley who thought that to climb one of the world's most perilous mountains just to shoot a film was unnecessary.[55] According to camerman Rexford Metz it was a boyhood fantasy of Eastwood's to climb such a mountain and that he got off on displaying such heroic machismo.[56] Despite Haston's warnings, the filming crew suffered a number of accidents. A 27-year old English climber, David Knowles, who was acting as body double and photographer was killed during filming, with Hoover narrowly escaping. The event was a devastating blow to the crew and Eastwood who almost pulled the plug on the project but proceeded because he didn't want to think Knowles had died in vain.[57] Eastwood continued to insist on doing all his own climbing and stunts, despite potentially being just seconds from instant death. Cameraman Frank Stanley would later fall during the shoot but survived and was a wheelchair user for sometime and taken out of action.[58] Stanley, who later managed to complete filming after a delay under pressure from an unsympathetic Eastwood, would later blame Eastwood for the accident due to a lack of preparation, describing him both as a director and an actor as "a very impatient man who doesn't really plan his pictures or do any homework. He figures he can go right in and sail through these things".[59] Stanley was never hired by Eastwood or Malpaso Productions again. Several other accidents and events apparently took place during the filming which were protected from public knowledge by the producers.[57]

Upon its release in May 1975, The Eiger Sanction was panned by most critics. A number of critics criticized Eastwood's performance as Hemlock, who fell short of the sophistication of the character portrayed in the book with Playboy describing the film as "a James Bond reject".[60]Joy Gould Boyum of the Wall Street Journal remarked that, "the film situates villainy in homosexuals, and physically disabled men".[60] Several critics failed to understand the plot and Pauline Kael of New York Magazine described the film as "a total travesty".[60] The film was a commercial failure, receiving only $23.8 million at the box office, although the film has since become a cult classic among rock climbers.[60] Once again Eastwood would blame the production company for the poor earnings and publicity of the film and departed from Universal Studios once again, forming a long-lasting agreement with Warner Brothers through Frank Wells that would transcend over 35 years of cinema and remain intact to this day.[61]

The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

_Town_Site%2C_Utah1.jpg)

The story to The Outlaw Josey Wales was inspired by a 1972 novel by an apparent Native Indian uneducated writer Forrest Carter, originally titled Gone to Texas and later retitled The Rebel Outlaw:Josey Wales. Later it would be revealed that Forrest Carter's identity was fake, and that the real author was Asa Carter, a onetime racist and supporter of Ku Klux Klan school of politics.[62] The script was worked on by Sonia Chernus and producer Bob Daley at Malpaso and Eastwood himself paid some of the money to obtain the screen rights.[62] It would be a Western, and the lead character, Josey Wales, is a rebel southerner who refuses to surrender his arms after the American Civil War and is chased across the old southwest by a group of enforcers. Michael Cimono and Philip Kaufman later overlooked the writing of the script, aiding Chernus. Kaufman wanted the film to stay as close to the story of the novel as possible and retained many of the mannerisms in Josey Wales's character which Eastwood would display on screen such as his distinctive lingo with words like "reckin", "hoss" (instead of "horse") and "ye" (instead of "you") and spitting tobacco juice on animals and victims.[62] The characters of Wales, the Cherokee chief, Navajo squaw and the old settler woman and her daughter all appeared in the novel.[63]

Cinematographer Bruce Surtees, James Fargo and Fritz Manes scouted for locations and eventually found sites in Utah, Arizona and Wyoming even before they saw the final script.[63] Kaufman cast Chief Dan George, who had been nominated for an Academy Award for Supporting Actor in Little Big Man as the old Cherokee Lone Watie. Sondra Locke, a previous Academy Award nominee, was cast by Eastwood against Kaufman's wishes,[64] as the daughter of the old settler woman, Laura Lee. This marked the beginning of a close relationship between Eastwood and Locke that would last six films and the beginning of a raging romance that would last into the late 1980s. The film featured Eastwood's seven-year-old son Kyle Eastwood. With Ferris Webster hired as editor and Jerry Fielding as musical composer.

Principal photography for The Outlaw Josey Wales began in mid-October 1975.[64] A rift between Eastwood and Kaufman developed during the filming. Kaufman insisted on filming with a meticulous attention to detail which caused disagreements with Eastwood, not to mention the attraction the two shared towards Locke and apparent jealousy on Kaufman's part in regards to their emerging relationship.[65] One evening Kaufman insisted on finding a beer can as a prop to be used in a scene but whilst he was absent, Eastwood ordered Surtees to quickly shoot the scene as light was fading and then drove away, leaving Kaufman even before he had returned.[66] Soon after filming moved to Kanab, Utah on October 24, 1975, Kaufman was notoriously fired under Eastwood's command by producer Bob Daley.[67] The sacking caused an outrage amongst the Directors Guild of America and other important Hollywood executives, since the director had completed all of the preproduction and had already worked hard on the film.[67] Pressure mounted on Warner Brothers and Eastwood to back down, and refusal to do so resulted in a fine, reported to be around $60,000 for the violation.[67] Symbolically, this resulted in the Director's Guild passing new legislation, known as 'the Clint Eastwood Rule' in which they reserved the right to impose a major fine on a producer for discharging a director and replacing him with himself.[67] From then on the film was directed by Eastwood himself with Daley second in command, but with Kaufman's planning already in place, the team were able to finish making the film efficiently.

"Eastwood is such a taciturn and action-oriented performer that it's easy to overlook the fact that he directs many of his movies -- and many of the best, most intelligent ones. Here, with the moody, gloomily beautiful, photography of Bruce Surtees, he creates a magnificent Western feeling"

Upon its release in August 1976, The Outlaw Josey Wales was widely acclaimed by critics. Many critics and viewers saw Eastwood's role as an iconic one, relating it with much of America's ancestral past and the destiny of the nation after the American Civil War.[69] The film was pre-screened at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities in a six-day conference entitled, Western Movies: Myths and Images. Some 200 film critics, academics and directors including critics Jay Cocks and Arthur Knight and directors such as King Vidor, William Wyler and Howard Hawks were invited to the screening.[69] The film would later appear in Time magazines Top 10 films of the year.[70] Roger Ebert compared the nature and vulnerability of Eastwood's portrayal of Josey Wales with his Man With No Name character in his Dollars westerns and praised the atmosphere of the film. The film was awarded a 97% rating on the critical website Rotten Tomatoes.

The Enforcer (1976)

After The Outlaw Josey Wales, Eastwood was offered the role of Benjamin L. Willard in Francis Coppola's Apocalypse Now but declined as he did not want to spend weeks in the Philippines shooting it.[71] He was offered the part of a platoon leader in Ted Post's Vietnam War film, Go Tell the Spartans. Eastwood refused the part and Burt Lancaster played the character instead.[71] Eastwood was presented with a script called Moving Target which had potential but needed a major rewrite. In the end it was decided to make a third Dirty Harry film. The script, devised by Stirling Silliphant had Harry up against a San Francisco Bay area Symbionese Liberation Army type group, which in real life had terrorized the area in 1974 with ruthless kidnappings and violence, and the film would end in a shoot out at the gang's hideout on Alcatraz island.[72] Eastwood met Silliphant in a restaurant in Tiburon and instantly took a liking to the script, particularly the shoot out and the idea of Callahan having a woman as a police partner, his worst nightmare, a relationship which would gradually blossom during the course of the film and provide a backbone to the film's structure as they encounter different situations, from initial hatred to a fondess of each other and Callahan's genuine sorrow on her being shot in the finale.[73] Silliphant wrote the script throughout late 1975 and early 1976 and delivered his draft to Eastwood in February 1976. Whilst Eastwood approved, he believed there was just a little too much emphasis on relationship rather than action and was concerned the fans might not approve, so Dean Riesner revised the script, keeping the structure but reducing Callahan's lines and placing in more action and making the mayor as the subject of the gang's kidnapping.[73] Kate Moore was originally proposed to play the part of the female cop, but in the end it went to Tyne Daly. Her casting was initially uncertain, given that she turned down the role three times. She objected to the way her character was treated in parts to the film and showed concern that two members of the police force falling in love on the job was problematic, given that they would be putting their lives in jeopardy by not reaching peak efficiency. Daly was permitted to read the drafts of the script developed by Riesner and had significant leeway in the development of her character, although after seeing the film at the premiere was horrified by the extent of the violence.[74][75]

With James Fargo to direct, filming commenced in the San Francisco bay area in the summer of 1976. Eastwood was initially still dubious with the quantity of his lines and preferred a less talkative approach, something perhaps embedded in him by Sergio Leone.[76] He encountered serious difficulties in the bar scene with Harry and Kate (Daly) and the scene had to be shot at least 6 times.[76] The film ended up considerably shorter than the previous Dirty Harry films, and was cut to 95 minutes.[77] Upon release in the fall of 1976, The Enforcer was a major commercial success and grossed a total of $100 million, $60 million in the United States and easily became Eastwood's best selling film to date,[75] earning more than some of his previous films combined. Critically, Eastwood's performance was poorly received and was named "Worst Actor of the Year" by the Harvard Lampoon and the film was criticised for its level of violence.[75] His performance in the third installment was overshadowed by positive reviews given to Daly in her convincing role as the strong-minded female cop.[77] Feminist reviewers in particular gave Daly rave reviews, with Marjorie Rosen remarking that Malpaso "had invented a heroine of steel" and Jean Hoelscher of Hollywood Reporter praising Eastwood for abandoning his ego in casting such as strong female actress in his film.[75]

The Gauntlet (1977)

In 1977, Eastwood directed and starred in The Gauntlet, in which he played a down-and-out cop who falls in love with a prostitute whom he's assigned to escort from Las Vegas to Phoenix in order for her to testify against the mob. Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand were originally cast as the film's stars.[78] Fighting between the two forced them to drop out of the project, with Eastwood and Locke replacing them. References to political corruption and organized crime were depicted in the film. Although a moderate hit with the viewing public, critics were mixed about the film, with many believing it was overly violent. Eastwood's long time nemesis Pauline Kael called it "a tale varnished with foul language and garnished with violence". Roger Ebert, on the other hand, gave it three stars and called it "...classic Clint Eastwood: fast, furious, and funny."[79]David Ansen of Newsweek wrote, "You don't believe a minute of it, but at the end of the quest, it's hard not to chuckle and cheer".[72]

Every Which Way But Loose (1978)

In 1978, Eastwood starred in Every Which Way but Loose an uncharacteristic, offbeat comedy role. Eastwood played Philo Beddoe, a trucker and brawler who roamed the American West, searching for a lost love, while accompanying his best brother/manager Orville and his pet orangutan, Clyde. The script, written by Jeremy Joe Kronsberg had been turned down by many other big production companies in Hollywood and most of Eastwood's production team agents all though it was ill advised.[80] Bob Hoyt, with whom Eastwood had contacts through his Malpaso secretary Judy Hoyt, as well as Eastwood's long term friend Fritz Manes, thought it showed promise and eventually convinced Warner Brothers to buy it. An orangutan named Manis was brought in to play Clyde, Geoffrey Lewis as the dimwitted Orville, Beverly D'Angelo as his girlfriend, and Sondra Locke as Lynn Halsey-Taylor, the country and western barroom singer.

Songwriter Snuff Garrett was hired to write songs for the film, including three for Locke's character, something which proved problematic as Locke was not a professional singer.[81] Upon its release, the film was a surprising success and became Eastwood's most commercially successful film at the time and ranks high amongst those of his career to date, becoming the second-highest grossing film of the year.[82] It was panned by the critics, with Variety commenting that, "This film is so awful it's almost as if Eastwood is using it to find out how far he can go - how bad a film he can associate himself with". David Ansen of Newsweek described the film as, "plotless junk heap of moronic gags, sour romance and fatuous fisticuffs.[82]

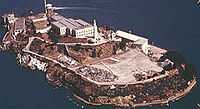

Escape from Alcatraz (1979)

.jpg)

In 1979, Eastwood starred in the fact-based movie Escape from Alcatraz, based on the true story of Frank Lee Morris, who, along with John and Clarence Anglin escaped from the notorious Alcatraz prison in 1962. The inmates dug through the walls with their spoons, made papier-mache dummies as decoys and made a raft out of raincoats and escaped across San Francisco Bay, never to be seen again. The script to the film was written by Richard Tuggle, based on the 1963 non-fiction account by J. Campbell Bruce.[83] Eastwood was drawn to the role as ringleader Frank Morris and agreed to star, providing Don Siegel directed under the Malpaso banner. Siegel insisted that it be a Don Siegel film and out-maneouvered Clint by purchasing the rights to the film for $100,000. This created a rift between the friends, causing Siegel to depart to Paramount, a rival studio.[83] Although their disagreement was later patched up and Siegel agreed for it to be a Malpaso-Siegel production, Siegel would never direct an Eastwood picture again. As Siegel and Tuggle worked on the script, the producers paid $500,000 to restore the decaying prison and recreate the cold atmosphere, although some interiors had to be recreated within the studio. The film was a major success, earning $34 million in the states alone and was widely acclaimed by critics, marking the beginning of a newly found critical praise Eastwood began to receive in the early 1980s. Frank Rich of Time described the film as "cool, cinematic grace", while Stanley Kauffman of The New Republic called it "crystalline cinema".[84]

See also

References

- ↑ Frayling (1992), p. 7

- ↑ Smith (1993), p.76

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.225

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.226

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 McGilligan (1999), p.179

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 181

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 182

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 McGilligan (1999), p.183

- ↑ Kauffman, Stanley (August 1, 1970). "Stanley Kauffman on Films". The New Republic.

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p. 227

- ↑ Canby, Maslin & Nichols (1999)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 184

- ↑ Kelly's Heroes, rottentomatoes.com; accessed June 16, 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 185

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 187

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.186

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 McGilligan (1999), p. 189

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 190

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 192

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 McGilligan (1999), p. 193

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 204

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.196

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 194

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 260

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 McGilligan (1999), p.195

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 205

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 206

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 207

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 209

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 210

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 211

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 212

- ↑ Clint Eastwood as Superman or James Bond? ‘It could have happened,’ he says (updated)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 218

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 217

- ↑ Greenspun, Roger (July 20, 1972). "Joe Kidd (1972)". The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 219

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 221

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 223

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 228

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 229

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 230

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 McGilligan (1999), p.231

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.233

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 McGilligan (1999), p.234

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 235

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 236

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 237

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 239

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 McGilligan (1999), p.240

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 McGilligan (1999), p. 241

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 242

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 243

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 244

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 McGilligan (1999), p. 245

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 248

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 247

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.249

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 250

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 McGilligan (1999), p. 253

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.256

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 McGilligan (1999), p.257

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 258

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 McGilligan (1999), p.261

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.262

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 263

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 McGilligan (1999), p.264

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1976). "The Outlaw Josey Wales". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 266

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 267

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 McGilligan (1999), p.268

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 McGilligan (1999), p.273

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 McGilligan (1999), p.274

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 275

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 McGilligan (1999), p. 278

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 McGilligan (1999), p.276

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 McGilligan (1999), p.277

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 279

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1977). "The Gauntlet". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 293

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 299

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 302

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 McGilligan (1999), p. 304

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p. 307

Daily Review newspaper, Hayward, California. 25 August 1970. Review of Erroll Garner show.https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1891660025710&set=o.212471978792862&type=3&theater

Bibliography

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.