Clint Eastwood in the 1960s

| |

This article is part of a series on Clint Eastwood |

|---|---|

In the 1960s, Clint Eastwood rose to fame in the Dollars Trilogy which would break him into mainstream cinema in the United States.

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

In late 1963, an offer was made to Eastwood's co-star Eric Fleming on Rawhide to star in an Italian made western, originally to be named The Magnificent Stranger (A Fistful of Dollars) to be directed in a remote region of Spain by a relative unknown at the time, Sergio Leone. However, the money was not much, and Fleming always set his sights high on Hollywood stardom, and rejected the offer immediately.[1] A variety of actors, including Charles Bronson, Steve Reeves, Richard Harrison, Frank Wolfe, Henry Fonda, James Coburn and Ty Hardin[2] were considered for the main part in the film,[3] and the producers established a list of lesser-known American actors, and asked the aforementioned Richard Harrison for advice. Harrison had suggested Clint Eastwood, whom he knew could play a cowboy convincingly. Harrison later said: "Maybe my greatest contribution to cinema was not doing Fistful of Dollars, and recommending Clint for the part".[4]

Leone watched Rawhide upon the advice of Claudia Sartori, an agent working at the William Morris Agency in Rome. He viewed Episode 91, Incident of the Black Sheep, dubbed into Italian.[1] Leone intended to focus on Fleming, but claimed to find entirely distracted, watching Eastwood. Leone said, "What fascinated me about Clint, above all, was his external appearance. I noticed the lazy, laidback way he just came on and stole every single scene from Fleming. His laziness is what came over so clearly."[1] However, Leone's claim that he was entirely distracted by watching Eastwood is somewhat contradicted by the fact that, after Fleming turned down the role, he was urged by Sartori to rewatch the episode and to concentrate on Eastwood.[5]

An offer was made to Eastwood through Irving Leonard. However, Ruth Marsh of the Marsh Agency, who had supported Clint since the 1950s, and his wife Maggie, conspired to manoeuvre past Leonard, when he had refused the funds to provide a reel of Eastwood in Rawhide to the Italian producers.[5] They sent a reel to Jolly Film and agent Filippo Fortini, who had agency contacts with actor Philippe Hersent, the husband of writer Geneviève Hersent and the Italian intermediary of the Marsh Agency.[5] Eastwood initially thought the same as Fleming. After all he was already in a Western and was tired of it, and wanted to take months off to play golf and relax.[5] However, he was urged to read the script: a lone stranger rides into a Mexican frontier town, controlled and fought over by two gangs, and double-crosses them by playing them off against each other, while accepting money from both sides. After just ten pages, Eastwood recognised that the script was based on Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo. Eastwood had initially described the dialogue as "atrocious", but thought the storyline was an intelligent one.[5] Seeing potential, Irving Leonard cut Fortini out of the deal, so that the William Morris Agency would receive credit.[6] The agreement offered Clint $15,000, an air ticket and paid expenses for 11 weeks of filming.[6] Eastwood saw it as an opportunity to escape Rawhide and the states and saw it as a paid vacation and signed the contract which also threw in a bonus of a Mercedes automobile upon completion.[6]

Having never met Leone in advance, Eastwood arrived in Rome in May 1964 [actually, more likely in March or April 1964, since Eastwood was scheduled to shoot a scene ("interno miniera") with Josef Egger on April 2 at Grotte di Salone (Rome), and, furthermore, a candid photo of him and Marianna Koch, announcing the shooting on the film, appeared in the April 2 issue of the Italian newspaper L'Unita; see booklet (pages 44–45) accompanying the Per un pugno di dollari (collector's edition versione restaurata) Blu-ray disk AND see http://archivio.unita.it/[]] and was met by the Marsh agency contact there, writer Geneviève Hersent, rather than Fortini, along with Leone's assistants and a few journalists.[6] Eastwood met Leone later that day. Leone showed distaste for Eastwood's all-American style of dress, but was more impressed with meeting him in the flesh than seeing him on TV. Leone recollected, "Clint arrived, dressed with exactly the same bad taste as American students. I didn't care. It was his face and his way of walking that I was interested in".[7] Eastwood was instrumental in creating the Man With No Name character's distinctive visual style, that would appear throughout the Dollars trilogy. He had brought with him black jeans, purchased from a shop on Hollywood Boulevard, which he had bleached out and roughened up, a hat from a Santa Monica wardrobe firm, a leather bracelet and two Indian leather cases with two serpents,[7][8] and the trademark black cigars came from a Beverly Hills shop, though Eastwood himself is a non-smoker and hated the smell of cigar smoke.[9] Leone decided to use them in the film, and heavily emphasised the "look" of the mysterious stranger to appear in the film. Leone commented, "The truth is that I needed a mask more than an actor, and Eastwood at the time only had two facial expressions: one with the hat, and one without it".[8][10] Eastwood said about playing the Man With No Name character in the film,

"I wanted to play it with an economy of words and create this whole feeling through attitude and movement. It was just the kind of character I had envisioned for a long time, keep to the mystery and allude to what happened in the past. It came about after the frustration of doing Rawhide for so long. I felt the less he said the stronger he became and the more he grew in the imagination of the audience.[11]

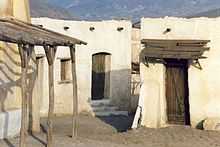

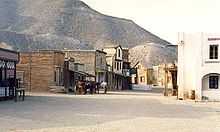

The first interiors for the film were shot at the Cinecittà studio on the outskirts of Rome, before quickly moving to a small village in Andalucia, Spain in an area also used for filming Lawrence of Arabia (1962) a few years earlier.[12] This would become a benchmark in the development of the spaghetti westerns. Leone would successfully create a new icon of a western hero, depicting a more lawless and desolate world than in traditional westerns. The trilogy would also redefine the stereotypical American image of a western hero and cowboy, creating a character gunslinger and bounty hunter, which was more of an anti hero than a hero and with a distinct moral ambiguity, unlike traditional heroes of western cinema in the United States, such as John Wayne.

Since the film was an Italian/German/Spanish co-production, there were major language barriers on the set. Eastwood mostly communicated with the Italian cast and crew through stuntman Benito Stefanelli, who acted as an interpreter for the production. The cast and crew stayed on location in Spain for nearly eleven weeks, during which Eastwood's wife Maggie came over for a visit. She found time to take a break in Toledo, Segovia and Madrid and regularly read Time magazine.[13]

Promoting A Fistful of Dollars was difficult, because no major distributor wanted to take a chance on a faux-Western and an unknown director. The film ended up being released in September, which is typically the worst month for sales. The film was shunned by the Italian critics, who gave it extremely negative reviews. However, at a grassroots level, its popularity spread, and it grossed $4 million in Italy, about three billion lire. American critics felt quite differently from their Italian counterparts, with Variety praising it as "a James Bondian vigor and tongue-in-cheek approach that was sure to capture both sophisticates and average cinema patrons".[14] The release of the film was delayed in the United States, because distributors feared being sued by Kurosawa. As a result, it was not shown in American cinemas until 1967.[14] This made it difficult for the American public or Hollywood to understand what was happening to Clint in Italy at the time. An American actor making films in Italy met with considerable prejudice, and was seen in Hollywood as taking a step backward, rather than a career development.[14]

For a Few Dollars More (1965)

Leone hired Eastwood to star in the second film of what would become a trilogy, For a Few Dollars More (1965). Leone was convinced that Jolly Film were withholding his share of the profits. He sued them and joined forces with producer Alberto Grimaldi, who founded the Produzioni Europee Associate (PEA) film company.[14] The company gave Leone a larger $350,000 budget to make the next film. Screenwriter Luciano Vincenzoni was brought in to write the script, which he wrote in nine days: two bounty hunters (Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef) pursuing a drug-addicted criminal (Volontè), planning to rob an impregnable bank.[15] Eastwood was given $50,000 in advance and a first-class plane ticket, but was not looking forward to having the cigar in his mouth again. At times, it made him feel sick during the first film.[15] For a Few Dollars More was shot in the spring and summer of 1965. Again, interiors of the film were shot at the Cinecittà studio in Rome, before they moved to Spain. During the filming Eastwood became close friends with screenwriter Vincenzoni, enjoyed his Italian cooking and attracted a lot of attention from his female guests.[16] Vincenzoni was very important in bringing the films to the states. He was fluent in English, and accompanied Leone to a cinema in Rome to show the new film to United Artist executives Arthur Krim and Arnold Picker, who showed much excitement about the film. An agreement was made with them, to purchase the rights to the film and a third film (which was yet to be written, let alone made) in advance, in the states for $900,000, advancing $500,000 up front and the right to half of the profits.[17][18]

Trouble brewed with Rawhide back in the United States. Eric Fleming quit the series (which lasted just thirteen more episodes without him). It faced increasing competition from the new World War II series Combat!, which eventually led to the demise of the series in January 1966. Eastwood met with producer Dino De Laurentiis in New York City and agreed to star in a non-Western five-part anthology production named Le Streghe or The Witches opposite Dino's wife, actress Silvana Mangano.[19] Eastwood travelled to Rome in late February 1966 and accepted the fee of $20,000 and a new Ferrari.[19] Acclaimed director Vittorio De Sica was hired to direct Eastwood's segment, called A Night Like Any Other. It was only nineteen minutes long and involved Clint playing a lazy husband, stuck in a stale marriage, who refuses to go and see A Fistful of Dollars in the cinema with his wife, preferring to stay home.[20] Meanwhile his wife dreams of having a fit, active husband who dances like Fred Astaire and is fantastic at making love.[20] Eastwood's installment only took a few days to shoot. It was not received well by critics, who described it as like "no other performance of his, is quite so 'un-Clintlike' ", with the New York Times disparaging it as a "throwaway De Sica".[20] Following this, Eastwood went to Paris to promote the premiere of A Few Dollars More with De Sica. He was already becoming very popular in France, labelled as the "new Gary Cooper".[20] In Paris, he met Pierre Rissient and had an affair with actress Catherine Deneuve.[20]

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Two months later Eastwood began working on The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, the final film of the Dollars trilogy, in which he again played the mysterious Man With No Name character. Lee Van Cleef was brought in again to play a ruthless fortune seeker, while Eli Wallach, a character actor noted for his appearance in The Magnificent Seven (1960), was hired to play the cunning Mexican bandit "Tuco", although the role was originally written for Volontè, who passed on working with Leone again.[21] The three become involved in a search for a buried cache of confederate gold, buried in a cemetery by a man named Jackson, in hiding as Bill Carson. Eastwood was not initially pleased with the script, and was concerned he might be upstaged by Wallach. He said to Leone, "In the first film I was alone. In the second, we were two. Here, we are three. If it goes on this way, in the next one I will be starring with the American cavalry".[21] Eastwood played hard-to-get in accepting the role, inflating his earnings up to $250,000, another Ferrari and 10% of the profits in the United States, when eventually released there. Eastwood was again encountering publicist disputes, between Ruth Marsh, who urged him to accept the third film of the trilogy, and the William Morris Agency and Irving Leonard, who were unhappy with Marsh's influence on Clint.[21] Eastwood banished Marsh from having any further influence in his career. He was forced to sack her as his business manager, via a letter sent by Frank Wells.[21] For some time after, Eastwood's publicity was handled by Jerry Pam of Gutman and Pam.[22]

Filming began at the Cinecittà studio in Rome in mid-May 1966, including the opening scene between Clint and Wallach, when The Man With No Name captures Tuco for the first time and sends him to jail.[22] The production then moved on to Spain's plateau region, near Burgos in the north, which would double for the extreme deep south of the United States. The western scenes were again shot in Almeria in the south.[23] This time, the production required more elaborate sets, including a town under cannon fire, an extensive prison camp and an American Civil War battlefield. For the climax, several hundred Spanish soldiers were employed to build a cemetery with several thousand grave stones to resemble an ancient Roman circus.[23] Top Italian cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli was brought in the shoot the film. He was prompted by Leone to pay more attention to light, than in the previous two films. Ennio Morricone composed the score once again. Leone was instrumental in asking Morricone to compose a track for the final Mexican stand-off scene in the cemetery, asking him to compose what felt like "the corpses were laughing from inside their tombs", and asked Delli Colli to creating a hypnotic whirling effect, interspersed with dramatic extreme close ups, to give the audience the impression of a visual ballet.[23]

Wallach and Eastwood flew to Madrid together. Between shooting scenes, Eastwood would relax and practice his golf swing.[24] One day, during the filming of the scene in which the bridge is blown up with dynamite, Eastwood, suspicious of explosives, urged his co-star Wallach to retreat up to the hilltop, saying, "I know about these things. Stay as far away from special effects and explosives as you can".[25] Just minutes later, crew confusion over saying "Vaya!", which was meant to be the signal for the explosion, but which a crew member had said without thinking to turn the cameras on, resulted in a premature explosion, resulting in the bridge having to be rebuilt.[25] The bridge was rebuilt for free by the Spanish army, that gallantly assumed responsibility, but the expense of redoing the scene and other costs, resulted in the film exceeding its budget by $300,000.

By the end of the film, Eastwood had finally had enough of Leone's perfectionist directorial traits. Leone, often forcefully, insisted on shooting scenes from many different angles, paying attention to the most minute of details; which would often exhaust the actors.[24] Leone, a glutton, was also a source of amusement for his excesses. Eastwood found a way to deal with the stresses of being directed by him by making jokes about him, and nicknamed him "Yosemite Sam" for his bad temperament.[24] Eastwood would never be directed by Leone again, later turning down the role as Harmonica in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Leone had personally flown to Los Angeles to give Eastwood the script. The role eventually went to Charles Bronson.[26] Years later, Leone would exact his revenge upon Clint, during the filming of Once Upon a Time in America (1984), when he described Eastwood's abilities as an actor as being like a block of marble or wax and inferior to the acting abilities of Robert De Niro, saying, "Eastwood moves like a sleepwalker between explosions and hails of bullets, and he is always the same - a block of marble. Bobby first of all is an actor, Clint first of all is a star. Bobby suffers, Clint yawns."[27]

The Dollars trilogy was not shown in the United States until 1967. A Fistful of Dollars opened in January, For a Few Dollars More in May and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly in December 1967.[28] Some twenty minutes were cut from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, particularly many scenes involving Lee Van Cleef, although Eastwood's remained intact. The trilogy was publicised as James Bond-type entertainment. All three films were successful in American cinemas, and turned Eastwood into a major film star in 1967, particularly the The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, which eventually collected $8 million in rental earnings.[28] However, upon release, all three were generally given bad reviews by critics (despite select American critics, who had seen the films in Italy, previously having positive outlooks) and marked the beginning of Eastwood's battle to win the respect of American film critics.[26] Judith Crist described A Fistful of Dollars as "cheapjack" while Newsweek described For a Few Dollars More as "excruciatingly dopey". The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was similarly panned by most critics upon US release. Renata Adler of the New York Times describing it as "the most expensive, pious and repellent movie in the history of its peculiar genre".[26] Variety commented that it is "a curious amalgam of the visually striking, the dramatically feeble and the offensively sadistic".[26] However, while Time highlighted the wooden acting, especially Eastwood's, critics such as Vincent Canby and Bosley Crowther of the New York Times highly praised Eastwood's coolness playing the tall, lone stranger. Leone's unique style of cinematography was widely acclaimed, even by some critics who disliked the acting.[26]

Post-Dollars Trilogy: A new American film star (1967–1969)

Eastwood spent much of late 1966 and 1967 dubbing the English-language version of the films and being interviewed, which left him feeling angry and frustrated.[27] Stardom brought more roles in the "tough guy" mold. Irving Leornard gave him a script to a new film, the American revisionist western Hang 'Em High, a cross between Rawhide and Leone's westerns, written by Mel Goldberg and produced by Leonard Freeman.[27] However, the William Morris Agency wanted him to star in a bigger picture, Mackenna's Gold with a cast of notable actors such as Gregory Peck, Omar Sharif and Telly Savalas. Eastwood, however, did not approve, and preferred the script for Hang 'Em High. He had one complaint, which he voiced to the producers, about the scene before the first hanging, where the hero is attacked by enemies. Eastwood believed that the scene would not be suitable in a saloon. They eventually agreed to introduce a whore scene, in which the attack takes place afterwards, as Eastwood enters the bar.[29] Eastwood signed for the film, for a salary of $400,000 and 25% of the net earnings to the film, playing the character of Cooper, a man accused by vigilantes of a cow baron's murder,lynched and left for dead and later seeking revenge.[29]

With the wealth generated by the Dollars trilogy, Leonard helped set up a new production company for Eastwood, Malpaso Productions, something he had long yearned for. It was named after a river on Eastwood's property in Monterey County.[30] Leonard became the company's president and arranged for Hang 'Em High to be a joint production with United Artists.[30] Directors Robert Aldrich and John Sturges were considered for the director's helm, but on the request of Eastwood, old friend Ted Post was brought in to direct, against the wishes of producer Leonard Freeman, who Eastwood had urged away.[31] Post was important in casting for the film. He arranged for Inger Stevens, of The Farmer's Daughter fame, to play the role of Rachel Warren. She had not heard of Eastwood or Sergio Leone at the time, but took an instant liking to Clint and accepted.[31] Pat Hingle, Dennis Hopper, Ed Begley, Bruce Dern and James MacArthur were also cast. Filming began in June 1967, in the Las Cruces area of New Mexico.[31] Additional scenes were shot at White Sands. Interiors were shot in MGM studios. Eastwood had considerable leeway in the production, especially in the script, which was altered in parts, such as the dialogue and setting of the barroom scene, to his liking.[32] The film became a major success after release in July 1968 and with an opening day revenue of $5,241 in Baltimore alone, it became the biggest United Artists opening in history, exceeding all of the James Bond films at that time.[33] It debuted at number five on Variety's weekly survey of top films, and had made its costs back within two weeks of screening.[33] It was widely praised by critics, including Arthur Winsten of the New York Post who described Hang 'Em High as "A Western of quality, courage, danger and excitement".[32]

Meanwhile, before Hang 'Em High had been released, Eastwood had set to work on Coogan's Bluff, a project which saw him reunite with Universal Studios after an offer of $1 million, more than doubling his previous salary.[33] Jennings Lang was responsible for the deal, a former agent of a director called Don Siegel, a Universal contract director who was invited to direct Eastwood's second major American film. Eastwood was not familiar with Siegel's work but Lang arranged for them to meet at Clint's residence in Carmel. Eastwood had now seen three of Siegel's earlier films and was impressed with his directing and the two became natural friends, forming a close partnership over five films in the years that followed.[34] The idea for Coogan's Bluff originated in early 1967 as a TV series and the first draft was drawn up by Herman Miller and Jack Laird, screenwriters for Rawhide.[35] It is about a character called Sheriff Walt Coogan, a lonely deputy sheriff working in New York City.

After Siegel and Eastwood had agreed to work together, Howard Rodman and three other writers were hired to devise a new script, as the new team scouted for locations, including New York and the Mojave desert.[34] However, Eastwood surprised the team one day by calling an abrupt meeting and professed to strongly disliking the script, which by now had gone through seven drafts, preferring Herman Miller's original concept.[34] This experience would also shape Eastwood's distaste for redrafting scripts in his later career.[34] Eastwood and Siegel decided to hire a new writer, Dean Riesner, who had written for Siegel in the Henry Fonda TV film Stranger on the Run some years previously. As Riesner drew up a new script, Eastwood was unwilling to communicate with the screenwriter, until one day, Riesner criticized one of the scenes which Eastwood had liked, which involved Coogan having sex with a girl called Linny Raven, in the hope that she would take him to her boyfriend". According to Riesner, Eastwood's " face went white and gave me one of those Clint looks".[36] The two soon reconciled their differences and worked on the script, with Eastwood having considerable input. Don Stroud was cast as the psychopathic criminal Coogan was chasing, Lee J. Cobb as the disagreeable New York City Police Department lieutenant, Susan Clark as a probation officer who falls for Coogan, and Tisha Sterling played the drug-addicted lover of Don Stroud's character.[36] Filming began in November 1967, even before the full script had been finalized.[36] The film was controversial for its portrayal of violence, but it launched a collaboration between Eastwood and Siegel that lasted more than ten years, and set the prototype for the macho hero that Eastwood would play in the Dirty Harry films. Coogan's Bluff also became the first collaboration with Argentine composer Lalo Schifrin, who would later compose the jazzy score to several of Eastwood's films in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly the Dirty Harry film series.

Eastwood was paid $850,000 in 1968 for the war epic Where Eagles Dare opposite Richard Burton.[37] However, Eastwood initially expressed that the script drawn up by Alistair Mclean was "terrible" and was "all exposition and complications".[37] The film was about a World War II squad parachuting into a Gestapo stronghold in the mountains, reachable only by cable car, with Burton playing the squad's commander and Eastwood his right-hand man. He was also cast as Two-Face in the Batman television series, but the series was cancelled before he played the part.

In 1969, Eastwood branched out, by starring in his only musical, Paint Your Wagon. He and fellow non-singer Lee Marvin played gold miners who share the same wife (played by Jean Seberg). Production for the film was plagued with bad weather and delays and the future of the director's career (Joshua Logan) was in doubt.[38] It was extremely high budget for this period, and eventually exceeded $20 million.[38] Although the film received mixed reviews, it was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.

Shortly before Christmas 1969, Eastwood's longtime business manager Irving Leonard died, aged 53. This came as a shock. He was replaced as Malpaso by an old friend. Bob Daley became important in production and under the terms of Leonard's will, Roy Kaufman and Howard Bernstein would assume responsibility of the company finances.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 McGillagan (1999), p.126

- ↑ Relive the thrilling days of the Old West in film | TahoeBonanza.com.

- ↑ A Fistful of Dollars.

- ↑ Richard Harrison interview.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 McGillagan (1999), p.127

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 McGillagan (1999), p.128

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McGillagan (1999), p.129

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 McGillagan (1999), p.131

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.132

- ↑ (Italian only) http://www.cinemadelsilenzio.it/index.php?mod=interview&id=17

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.133

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.134

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.137

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 McGillagan (1999), p.144

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McGillagan (1999), p.145

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.146

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.148

- ↑ Frayling, Christopher (2000). Sergio Leone: Something To Do With Death. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-16438-2.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 McGillagan (1999), p.150

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 McGillagan (1999), p.151

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 McGillagan (1999), p.152

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 McGillagan (1999), p.153

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 McGillagan (1999), p.154

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 McGillagan (1999), p.155

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 McGillagan (1999), p.156

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 McGillagan (1999), p.158

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 McGillagan (1999), p.159

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 McGillagan (1999), p.157

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 McGillagan (1999), p.160-1

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 McGillagan (1999), p.162

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 McGillagan (1999), p.163

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 McGillagan (1999), p.164

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 McGillagan (1999), p.165

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 McGillagan (1999), p.167

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.166

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 McGillagan (1999), p.169

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 McGillagan (1999), p.172

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 McGillagan (1999), p.173

- ↑ McGillagan (1999), p.177

Bibliography

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.