Cleveland Elementary School shooting (San Diego)

| Cleveland Elementary School shooting | |

|---|---|

| Location | San Diego, California |

| Date | January 29, 1979 |

| Target | Students and faculty at Cleveland Elementary School |

Attack type | School shooting, murder |

| Weapons | Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic .22 caliber rifle |

| Deaths | 2 |

Non-fatal injuries | 9 |

| Perpetrator | Brenda Spencer |

The Cleveland Elementary School shooting took place on January 29, 1979, in San Diego, California. Shots were fired at a public elementary school. The principal and a custodian were killed. Eight children and a police officer were injured. A 16-year-old girl, Brenda Spencer,[1] who lived in a house across the street from the school, was convicted of the shootings. Tried as an adult, Spencer pled guilty to two counts of murder and assault with a deadly weapon, and was given an indefinite sentence. She is currently in prison.

A reporter got through to Spencer after the shooting while she was still in the house. He reported asking Spencer why she carried out the shooting. She answered: "I don't like Mondays".[2] Spencer later said she did not recall making the remark.

Brenda Spencer

| Brenda Spencer | |

|---|---|

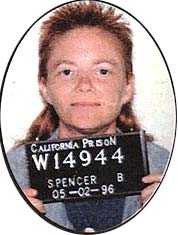

Spencer in 1996 | |

| Born |

Brenda Ann Spencer April 3, 1962 San Diego, California |

| Parent(s) |

Wallace Spencer Dot Spencer |

Brenda Ann Spencer (born April 3, 1962) lived in the San Carlos neighborhood of San Diego, California in a house across the street from Grover Cleveland Elementary School, San Diego Unified School District.[3] Aged 16, she was 5'2", unusually thin, and had bright red hair.[4][5][6] Acquaintances said Spencer expressed hostility toward policemen, had talked about shooting one, and had talked of doing something big to get on TV.[2][5] Although Spencer showed exceptional ability in photography, winning first prize in a Humane Society competition, she was generally uninterested in school and one teacher recalled frequently inquiring if she was awake in class. Later, during tests while she was in custody, it was discovered Spencer had an injury to the temporal lobe of her brain. It was attributed to an accident on her bicycle.[7]

After her parents separated, she lived with her father, Wallace Spencer, in virtual poverty; they slept on a single mattress on the living room floor, with empty alcohol bottles throughout the house.[8][9] Spencer is said to have self-identified as "having been gay from birth."[10]

In early 1978, staff at a facility for problem pupils, which Spencer had been referred to due to truancy, informed her parents that she was suicidal. That summer Spencer, who was known to hunt birds in the neighborhood, was arrested for shooting out the windows of Cleveland Elementary with a BB gun, and burglary.[2] In December a psychiatric evaluation arranged by her probation officer recommended Spencer be admitted to a mental hospital due to her depressed state, but her father refused to give permission. For Christmas 1978 he gave her a Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic .22 caliber rifle with a telescopic sight and 500 rounds of ammunition.[9][11] Spencer later said: "I asked for a radio and he bought me a gun." When asked why he might have done that, she answered, "I felt like he wanted me to kill myself."[10][12]

Shooting

On the morning of Monday, January 29, 1979, Spencer began shooting from her home at children who were waiting outside Cleveland Elementary School for principal Burton Wragg to open the gates.[3] She injured eight children. Wragg was killed while trying to help the children. Custodian Mike Suchar was killed while trying to pull Wragg to safety.[11] A police officer responding to a call for assistance during the incident was wounded in the neck as he arrived.[11]

After firing thirty rounds of ammunition, Spencer barricaded herself inside her home for several hours. While there, she had a telephone conversation with a journalist who reported that she had said "I don't like Mondays" in reply to his question why she had done it. She also spoke with police negotiators, telling them those she had shot had made easy targets, and that she was going to "come out shooting."[11] Spencer has been repeatedly reminded of these statements at parole hearings.[13] Ultimately, she surrendered.[10][11] Police officers found beer and whiskey bottles cluttered around the house, but said Spencer did not appear to be intoxicated at the time of her arrest.[11]

Spencer was cited as the inspiration for the song "I Don't Like Mondays", written by Bob Geldof for his band the Boomtown Rats, which was released later that year.[14] Geldof and his band were in San Diego performing at The Roxy Theater, a small movie theater and concert hall in the Pacific Beach part of town, on February 27, 1979, and the preliminary legal proceedings against Spencer were headlining local news broadcasts. I Don't Like Mondays was also the title of a 2006 television documentary about the event.[15]

Imprisonment of Spencer

Spencer was tried as an adult, and pleaded guilty to two counts of murder and assault with a deadly weapon. She was sentenced to 25 years to life. In prison Spencer was diagnosed as an epileptic and received medication to treat epilepsy and depression. While at the California Institution for Women in Chino, California, she worked repairing electronic equipment.[16][17]

Under the terms of her indeterminate sentence, in 1993 Spencer became eligible for hearings to consider her suitability for parole. In practice very few with any conviction on a charge of murder were able to obtain parole in California before 2011.[18] She has been unsuccessful at four Board of Parole Hearings. At the first hearing Spencer said she had hoped police would shoot her, and that she had been a user of alcohol and drugs at the time of the crime; which contradicted the results of drug tests done when she was taken into custody. In her 2001 hearing, Spencer for the first time said her father had been subjecting her to beatings and sexual abuse; he said the allegations were not true. The parole board chairman said that, as she had not previously told any prison staff about the allegations, he doubted whether they were true.[19] In 2005, a San Diego Deputy District Attorney cited an incident of self-harm (branding words on her skin with hot wire) from four years earlier as showing Spencer was psychotic and unfit to be released.[16] In 2009 the board again refused her application for parole, and ruled it would be 10 years before she would be considered again.[20][21]

Aftermath

Almost exactly 10 years after the events at Cleveland Elementary, there was another shooting at another school named Cleveland Elementary, this one in Stockton, California. Five students were killed and 30 were injured. The event was a grim reminder to survivors of the 1979 shooting, who described themselves as "shocked, saddened, horrified" by the eerie similarities to their own traumatic experience.[22]

San Diego's Cleveland Elementary School was closed in 1983, along with a dozen other schools around the city, due to declining enrollment. In the ensuing decades, it was leased to several different charter and private schools.[23] The site currently houses the Magnolia Science Academy, a public charter middle school serving students in grades 6-8.[24]

Other arguments

Laura L. Lovett, a founding co-editor of the Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth and an associate professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, argued in a CNN opinion essay that the San Diego shooting was overlooked by society because the perpetrator was a female. Lovett said that society can learn from cases of attacks instigated by women.[25]

References

- ↑ NOTE: Although she is often referred to in the press as Brenda Ann Spencer, authoritative sources such as the state of California and her defense attorneys call her Brenda Spencer without the middle name. See talk page.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "School Sniper Bragged Of "Something Big To Get On TV"". AP. January 30, 1979. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "School Shooter Brenda Spencer Denied Parole". CBS 8 news. Aug 21, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ↑ January 30, 1979 Los Angeles Times "Lonely Girl Conceals Violent Fantasy"

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Sniping suspect had a grim goal". The Milwaukee Journal. January 29, 1979. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of School Crime and Violence - Page 454

- ↑ School Shootings: International Research, Case Studies, and Concepts, By Thorsten. Seeger, Peter. Sitzer. Page 251-253

- ↑ The Milwaukee Journal - Jan 29, 1979

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 School Shootings, 2013, Nils Böckler, Thorsten Seeger, Peter Sitzer, Wilhelm Heitmeyer

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 School Shootings, 2013, By Nils Böckler, Thorsten Seeger, Peter Sitzer, Wilhelm Heitmeyer Page 257

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 "Sniping Suspect Had a Grim Goal". The Milwaukee Journal. January 30, 1979. pp. Pt. I, 4. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ↑ "'I Don't Like Mondays'". Boomtown Rats.co.uk. 2003. Retrieved February 29, 2012., with details about the case.

- ↑ School Shootings, 2013, By Nils Böckler, Thorsten Seeger, Peter Sitzer, Wilhelm Heitmeyer Page 250 and 257

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara (September 29, 2005). "Urban Legends Reference Pages: Music (I Don't Like Mondays)". Snopes.com. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ↑ "I Don't Like Mondays (TV 2006)". IMDb. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 San Diego Reader, March 10, 2005

- ↑ School Shootings, 2013, By Nils Böckler, Thorsten Seeger, Peter Sitzer, Wilhelm Heitmeyer Page 257

- ↑ In California, Victims’ Families Fight for the Dead, NYT August 19, 2011

- ↑ School Shootings, 2013, by Nils Böckler, Thorsten Seeger, Peter Sitzer, Wilhelm Heitmeyer Page 248

- ↑ Staff (June 19, 2001). "Parole Denied in School Shooting". Associated Press (via USA Today). Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Staff (August 13, 2009). "School Shooter Brenda Spencer Denied Parole". KFMB-TV. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ↑ Granberry, Michael (January 19, 1989). "Victims of San Diego School Shooting Are Forced to Cope Again 10 Years Later". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Closed Public School Sites in San Carlos". kuraoka.org. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "Home page". Magnolia Science Academy. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ Lovett, Laura L. (December 21, 2012). "Opinion: Female Mass Shooter Can Teach Us About Adam Lanza". In America (blog of CNN). Retrieved December 22, 2012.

External links

- "The Boomtown Rats - I Don't Like Mondays". Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2013.