Class logic

Class logic is a logic in its broad sense, whose objects are called classes. In a narrower sense, one speaks of a class of logic only if classes are described by a property of their elements. This class logic is thus a generalization of set theory, which allows only a limited consideration of classes.

Class logic in the strict sense

The first class logic in the strict sense was created by Giuseppe Peano in 1889 as the basis for his arithmetic (Peano Axioms). He introduced the class term, which formally correctly describes classes through a property of their elements. Today the class term is denoted in the form {x|A(x)}, where A(x) is an arbitrary statement, which all class members x meet. Peano axiomatized the class term for the first time and used it fully. Gottlob Frege also tried establishing the arithmetic logic with class terms in 1893; Bertrand Russell discovered a conflict in it in 1902 which became known as Russell's paradox. As a result, it became generally known that you can not safely use class terms.

To solve the problem, Russell developed his type theory from 1903 to 1908, which allowed only a very much restricted use of class terms. In the long term she not prevailed but, but more comfortable and more powerful, 1907 initiated by Ernst Zermelo set theory. Not a class logic in the narrower sense, but in its present form (ZF or NBG) because it does not axiomatize the class term, but used only in practice as a useful notation. Willard Van Orman Quine described a set theory New Foundations (NF) in 1937, oriented not at Cantor, or Zermelo-Fraenkel, but on the theory of types. In 1940 Quine advanced NF to Mathematical Logic (ML). Since the antinomy of Burali-Forti was derived in the first version of ML,[1] Quine clarified ML, retaining the widespread use of classes, and took up a proposal by Hao Wang[2] introducing in 1963 in his theory of {x|A(x)} as a virtual class, so that classes are although not yet full-fledged terms, but sub-terms in defined contexts.[3]

After Quine, Arnold Oberschelp developed the first fully functional modern axiomatic class logic starting in 1974. It is a consistent extension of predicate logic and allows the unrestricted use of class terms (such as Peano).[4] It uses all classes that produce antinomies of naive set theory as a term. This is possible because the theory assumes no existence axioms for classes. It presupposes in particular any number of axioms, but can also take those and syntactically correct to formulate in the traditionally simple design with class terms. For example, the Oberschelp set theory developed the Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory within the framework of class logic.[5] Three principles guarantee that cumbersome ZF formulas are translatable into convenient classes formulas; guarantee a class logical increase in the ZF language they form without quantities axioms together with the axioms of predicate logic an axiom system for a simple logic of general class.[6]

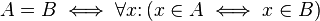

The principle of abstraction (Abstraktionsprinzip) states that classes describe their elements via a logical property:

The principle of extensionality (Extensionalitätsprinzip ) describes the equality of classes by matching their elements and eliminates the axiom of extensionality in ZF:

The principle of comprehension (Komprehensionsprinzip) determines the existence of a class as an element:

Bibliography

- Giuseppe Peano: Arithmetices principia. Nova methodo exposita. Corso, Torino u. a. 1889 (Auch in: Giuseppe Peano: Opere scelte. Band 2. Cremonese, Rom 1958, S. 20–55).

- G. Frege: Grundgesetze der Arithmetik. Begriffsschriftlich abgeleitet. Band 1. Pohle, Jena 1893.

- Willard Van Orman Quine: New Foundations for Mathematical Logic, in: American Mathematical Monthly 44 (1937), S. 70-80.

- Willard Van Orman Quine: Set Theory and its Logic. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1963 (Deutsche Übersetzung: Mengenlehre und ihre Logik (= Logik und Grundlagen der Mathematik. Bd. 10). Vieweg, Braunschweig 1973, ISBN 3-548-03532-9).

- Arnold Oberschelp: Elementare Logik und Mengenlehre (= BI-Hochschultaschenbücher 407–408). 2 Bände. Bibliographisches Institut, Mannheim u. a. 1974–1978, ISBN 3-411-00407-X (Bd. 1), ISBN 3-411-00408-8 (Bd. 2).

- Albert Menne Grundriß der formalen Logik (= Uni-Taschenbücher 59 UTB für Wissenschaft). Schöningh, Paderborn 1983, ISBN 3-506-99153-1 (Renamed Grundriß der Logistik starting with 5th Edition – The book shows, among other calcului, a possible application of calculus to class logic, based on the propositional and predicate calculus and carried the basic terms of formal systems to class logic. It also discusses briefly the paradoxes and type theory).

- Jürgen-Michael Glubrecht, Arnold Oberschelp, Günter Todt: Klassenlogik. Bibliographisches Institut, Mannheim u. a. 1983, ISBN 3-411-01634-5.

- Arnold Oberschelp: Allgemeine Mengenlehre. BI-Wissenschafts-Verlag, Mannheim u. a. 1994, ISBN 3-411-17271-1.

References

- ↑ John Barkley Rosser: Burali-Forti paradox. In: Journal of Symbolic Logic, Band 7, 1942, p. 1-17

- ↑ Hao Wang: A formal system for logic. In: Journal of Symbolic Logic, Band 15, 1950, p. 25-32

- ↑ Willard Van Orman Quine: Mengenlehre und ihre Logik. 1973, S. 12.

- ↑ Arnold Oberschelp: Allgemeine Mengenlehre. 1994, p. 75 f.

- ↑ The advantages of the class logic are shown in a comparison of ZFC in class logic and predicate logic form in: Arnold Oberschelp: Allgemeine Mengenlehre. 1994, p. 261.

- ↑ Arnold Oberschelp, p. 262, 41.7. The axiomatization is much more complicated, but here is reduced to a book-end to the essentials.