Cladogram

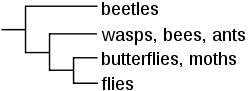

A cladogram (from Greek clados "branch" and gramma "character") is a diagram used in cladistics which shows relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to descendants or how much they have changed; many evolutionary trees can be inferred from a single cladogram.[1][2][3][4][5] A cladogram uses lines that branch off in different directions ending at groups of organisms. There are many shapes of cladograms but they all have lines that branch off from other lines. The lines can be traced back to where they branch off. These branching off points represent a hypothetical ancestor (not an actual entity) which would have the combined traits of the lines above it.[4][6] This hypothetical ancestor might then provide clues about what to look for in an actual evolutionary ancestor. Although traditionally such cladograms were generated largely on the basis of morphological characters, DNA and RNA sequencing data and computational phylogenetics are now very commonly used in the generation of cladograms.

Generating a cladogram

Molecular versus morphological data

The characteristics used to create a cladogram can be roughly categorized as either morphological (synapsid skull, warm blooded, notochord, unicellular, etc.) or molecular (DNA, RNA, or other genetic information).[7] Prior to the advent of DNA sequencing, all cladistic analysis used morphological data.

As DNA sequencing has become cheaper and easier, molecular systematics has become a more and more popular way to reconstruct phylogenies.[8] Using a parsimony criterion is only one of several methods to infer a phylogeny from molecular data; maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference, which incorporate explicit models of sequence evolution, are non-Hennigian ways to evaluate sequence data. Another powerful method of reconstructing phylogenies is the use of genomic retrotransposon markers, which are thought to be less prone to the problem of reversion that plagues sequence data. They are also generally assumed to have a low incidence of homoplasies because it was once thought that their integration into the genome was entirely random; this seems at least sometimes not to be the case, however.

Plesiomorphies and synapomorphies

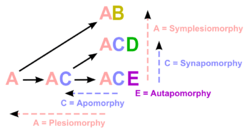

Researchers must decide which character states were present before the last common ancestor of the species group (plesiomorphies) and which only arose in the last common ancestor (synapomorphies) and do so by comparison to one or more outgroups. The choice of an outgroup is a crucial step in cladistic analysis because different outgroups can produce trees with profoundly different topologies. Note that only synapomorphies are of use in characterizing clades.

Homoplasies

A homoplasy is a character that is shared by multiple species due to some cause other than common ancestry.[9] The two main types of homoplasy are convergence (appearance of the same character in at least two distinct lineages) and reversion (the return to an ancestral character). Use of homoplasies when building a cladogram is sometimes unavoidable but is to be avoided when possible.

A well-known example of homoplasy due to convergent evolution would be the character, "presence of wings". Though the wings of birds, bats, and insects serve the same function, each evolved independently, as can be seen by their anatomy. If a bird, bat, and a winged insect were scored for the character, "presence of wings", a homoplasy would be introduced into the dataset, and this would confound the analysis, possibly resulting in a false evolutionary scenario.

Cladogram selection

There are several algorithms available to identify the "best" cladogram.[10] Most algorithms use a metric to measure how consistent a candidate cladogram is with the data. Most cladogram algorithms use the mathematical techniques of optimization and minimization.

In general, cladogram generation algorithms must be implemented as computer programs, although some algorithms can be performed manually when the data sets are trivial (for example, just a few species and a couple of characteristics).

Some algorithms are useful only when the characteristic data are molecular (DNA, RNA); other algorithms are useful only when the characteristic data are morphological. Other algorithms can be used when the characteristic data includes both molecular and morphological data.

Algorithms for cladograms include least squares, neighbor-joining, parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian inference.

Biologists sometimes use the term parsimony for a specific kind of cladogram generation algorithm and sometimes as an umbrella term for all cladogram algorithms.[11]

Algorithms that perform optimization tasks (such as building cladograms) can be sensitive to the order in which the input data (the list of species and their characteristics) is presented. Inputting the data in various orders can cause the same algorithm to produce different "best" cladograms. In these situations, the user should input the data in various orders and compare the results.

Using different algorithms on a single data set can sometimes yield different "best" cladograms, because each algorithm may have a unique definition of what is "best".

Because of the astronomical number of possible cladograms, algorithms cannot guarantee that the solution is the overall best solution. A nonoptimal cladogram will be selected if the program settles on a local minimum rather than the desired global minimum.[12] To help solve this problem, many cladogram algorithms use a simulated annealing approach to increase the likelihood that the selected cladogram is the optimal one.[13]

The basal position is the direction of the base (or root) of a rooted phylogenetic tree or cladogram. A basal clade is the earliest clade (of a given taxonomic rank[a]) to branch within a larger clade.

Cladogram statistics

Consistency index

The consistency index (CI) measures the amount of homoplasy in a cladogram. It is calculated by counting the minimum number of changes in a dataset and dividing it by the actual number of changes needed for the cladogram.

Retention index

The retention index (RI) is also a measure of the amount of homoplasy but also measures how well synapomorphies explain the tree. It is calculated taking the product of the maximum number of changes on a tree and the number of changes on the tree divided by the product of the maximum number of changes on the tree and the minimum number of changes in the dataset.

The rescaled retention index (RC) is obtained by multiplying the CI by the RI. The homoplasy index (HI) is simply 1-CI.

Incongruence length difference test (or partition homogeneity test)

The incongruence length difference test (ILD) is a measurement of how the combination of different datasets (e.g. morphological and molecular, plastid and nuclear genes) contributes to a longer tree. It is measured by first calculating the total tree length of each partition and summing them. Then replicates are made by making randomly assembled partitions consisting of the original partitions. The lengths are summed. A p value of 0.01 is obtained for 100 replicates if 99 replicates have longer combined tree lengths.

See also

References

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (2009). "Cladistic analysis or cladistic classification?". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 12: 94. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1974.tb00160.x.

- ↑ Foote, Mike (Spring 1996). "On the Probability of Ancestors in the Fossil Record". Paleobiology 22 (2): 141–51. JSTOR 2401114.

- ↑ Dayrat, Benoît (Summer 2005). "Ancestor-Descendant Relationships and the Reconstruction of the Tree of Life". Paleobiology 31 (3): 347–53. JSTOR 4096939.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Posada, David; Crandall, Keith A. (2001). "Intraspecific gene genealogies: Trees grafting into networks". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 16: 37. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)02026-7.

- ↑ Podani, János (2013). "Tree thinking, time and topology: Comments on the interpretation of tree diagrams in evolutionary/phylogenetic systematics". Cladistics 29 (3): 315. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00423.x.

- ↑ Schuh, Randall T. (2000). Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications. ISBN 978-0-8014-3675-8.

- ↑ DeSalle, Rob (2002). Techniques in Molecular Systematics and Evolution. Birkhauser. ISBN 3-7643-6257-X.

- ↑ Hillis, David (1996). Molecular Systematics. Sinaur. ISBN 0-87893-282-8.

- ↑ West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (2003). Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 353–376. ISBN 0-19-512235-6.

- ↑ Kitching, Ian (1998). Cladistics: The Theory and Practice of Parsimony Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850138-2.

- ↑ Stewart, Caro-Beth (1993). "The powers and pitfalls of parsimony". Nature 361 (6413): 603–7. Bibcode:1993Natur.361..603S. doi:10.1038/361603a0. PMID 8437621.

- ↑ Foley, Peter (1993). Cladistics: A Practical Course in Systematics. Oxford Univ. Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-19-857766-4.

- ↑ Nixon, Kevin C. (1999). "The Parsimony Ratchet, a New Method for Rapid Parsimony Analysis". Cladistics 15 (4): 407. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1999.tb00277.x.

External links

Media related to Cladograms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cladograms at Wikimedia Commons