Civil parishes in England

| Civil parish (England) | |

|---|---|

| Category | Parish |

| Location | England |

| Found in | Districts |

| Created by | Various, see text |

| Created | Various, see text |

| Number | 10,458 (as of 2010[1]) |

| Possible types |

City Community Neighbourhood Parish Town Village |

| Populations | 0–80,000 |

| Government |

City council Community council Neighbourhood council Parish council Town council Village council |

In England, a civil parish is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government below districts and counties, or their combined form, the unitary authority. It is an administrative parish, in contrast to an ecclesiastical parish.

A civil parish can range in size from a large town with a population of around 80,000 to a single village with fewer than a hundred inhabitants. In a limited number of cases a parish might include a whole city where city status has been granted by the Monarch. Reflecting this diverse nature, a civil parish may be known as a town, village, neighbourhood or community by resolution of its parish council. Approximately 35% of the English population live in a civil parish. As at 31 December 2010 there were 10,479 parishes in England.[2]

On 1 April 2014, Queen's Park became the first civil parish in Greater London.[3] Before 2008 their creation was not permitted within a London borough.[4]

History

Ancient origins

The division into ancient parishes was linked to the manorial system, with parishes and manors often sharing the same boundaries.[5] Initially the manor was the principal unit of local administration and justice in the early rural economy. Eventually the church replaced the manor court as the rural administrative centre and levied a local tax on produce known as a tithe.[5] Responsibilities such as relief of the poor passed in the medieval period increasingly from the Lord of the Manor to the rector, who in practice would delegate tasks among his vestry or the generally well-endowed monasteries. Following the dissolution of the monasteries, the power to levy a rate to fund relief of the poor was conferred on the parish authorities by the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601 and before and after this optional social change local (vestry-administered) charities are well-documented.[6]

The parish authorities were known as vestries and consisted of all the adult inhabitants of the parish. As the population was growing it became increasingly difficult to convene meetings as an open vestry. In some, mostly built up, areas the select vestry took over responsibility from the community at large. This innovation improved efficiency, but allowed governance by a self-perpetuating elite.[5] The administration of the parish system relied on the monopoly of the established English Church which after Henry VIII alternated between the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England before settling on the latter on the accession of Elizabeth I. As religious membership became more fractured, such as through the revival of Methodism, the legitimacy of the parish vestry came into question and the perceived inefficiency and corruption inherent in the system became a source for concern.[5] Because of this scepticism, during early the 19th century the parish progressively lost its powers to ad-hoc boards and other organisations, such as the loss of responsibility for poor relief through the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. Sanitary districts covered England in 1875 and Ireland three years later. The replacement boards were each able to levy their own rate in the parish. The church rate ceased to be levied in many parishes and became voluntary from 1868.[5]

Civil and ecclesiastical split

The ancient parishes diverged into two distinct units during the 19th century. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1866 declared all areas that levied a separate rate —including extra-parochial areas, townships, and chapelries— 'civil parishes'. The Anglican parishes with blanket coverage of England became officially termed 'ecclesiastical parishes' and after 1921 the responsibility of a parochial church council. The latter part of the 19th century saw most of the ancient irregularities inherited by the civil system cleaned up, with the majority of exclaves abolished. The United Kingdom Census 1911 notes that 8,322 (58%) of parishes in England and Wales were not identical for civil and ecclesiastical purposes.

Reform

Civil parishes in their modern sense were established afresh in 1894, by the Local Government Act 1894. The Act abolished vestries, set up urban districts and rural districts and established elected civil parish councils in all rural parishes with more than 300 electors. These were grouped into their rural districts. Boundaries were altered to avoid parishes being split between counties.

Urban civil parishes continued to exist; however they were generally coterminous with the urban district or municipal borough in which they lay, which took over almost all of their functions. Large towns which had previously been split between civil parishes were, for the most part, eventually consolidated into one parish. No parish councils were formed for urban parishes, and their only function was electing guardians to the often cross-district poor law unions. With the abolition of the Poor Law system in 1930, such urban parishes had only a nominal existence.

In 1965 civil parishes in London were formally abolished when Greater London was created, as the legislative framework for Greater London did not make provision for any local government body below a London borough. (Since all of London was previously part of a metropolitan borough, municipal borough or urban district, no actual parish councils were abolished.) In 1974 the Local Government Act 1972 retained civil parishes in rural areas and low-population urban districts, but abolished them in larger urban districts, especially boroughs. In non-metropolitan counties urban districts and municipal boroughs abolished rather than succeeded in many cases were part-retained, as new successor parishes. Urban areas that were considered too large to be single parishes were refused this permission and became unparished areas. The Act, however, permitted sub-division of all districts (apart from London boroughs, reformed in 1965) into civil parishes. For example, Oxford, whilst entirely unparished in 1974, now has four civil parishes, covering part of its area.

Revival

The creation of town and parish councils is encouraged in unparished areas. The Local Government and Rating Act 1997 created a procedure which gave local residents the right to demand that a new parish and council be created in unparished areas.[7] This was extended to London boroughs by the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007[8] - with this, the City of London is at present the only part of England where civil parishes cannot be created.

If a sufficient number of electors in an area of a proposed new parish (ranging from 50% in an area with less than 500 electors to 10% in one with more than 2,500) sign a petition demanding its creation, then the local district council or unitary authority must consider the proposal.[4] Recently established parish councils include Daventry (2003), Folkestone (2004), and Brixham (2007). In 2003 seven new parish councils were set up for Burton upon Trent, and in 2001 the Milton Keynes urban area became entirely parished, with ten new parishes being created. In 2003, the village of Great Coates (Grimsby) regained parish status. Parishes can also be abolished where there is evidence that this in response to "justified, clear and sustained local support" from the area's inhabitants.[4] Examples include Birtley, which was abolished in 2006 and Southsea abolished in 2010.[9][10]

Governance

Every civil parish has a parish meeting, consisting of all the electors of the parish. Generally a meeting is held once a year. A civil parish may have a parish council which exercises various local responsibilities prescribed by statute. Parishes with fewer than 200 electors are usually deemed too small to have a parish council, and instead will only have a parish meeting: an example of direct democracy. Alternatively several small parishes can be grouped together and share a common parish council, or even a common parish meeting. In places where there is no civil parish (unparished areas), the administration of the activities normally undertaken by the parish becomes the responsibility of the district or borough council. According to the government's Department for Communities and Local Government, in England in 2011 there are 9,946 parishes.[11] Since 1997 around 100 new civil parishes have been created, in some cases splitting existing civil parishes, but mostly by creating new ones from unparished areas.

Powers and functions

Typical activities undertaken by parish or town councils include:[12]

- The provision and upkeep of certain local facilities such as allotments, bus shelters, parks, playgrounds, public seats, public toilets, public clocks, street lights, village or town halls, and various leisure and recreation facilities.

- Maintenance of footpaths, cemeteries and village greens

- Since 1997 parish councils have had new powers to provide community transport (such as a minibus) and crime prevention measures (such as CCTV) and to contribute money towards traffic calming schemes.

- Parish councils are supposed to act as a channel of local opinion to larger local government bodies, and as such have the right to be consulted on any planning decisions affecting the parish.

- Giving of grants to local voluntary organisations, and sponsoring public events, including entering Britain in Bloom.

The role played by parish councils varies. Smaller parish councils have only limited resources and generally play only a minor role, while some larger parish councils have a role similar to that of a small district council. Parish councils receive funding by levying a "precept" on the council tax paid by the residents of the parish.

Councillors and elections

Parish councils comprise volunteer councillors who are elected to serve for four years. Decisions of the council are carried out by a paid officer, typically known as a parish clerk. Councils may employ additional people (including bodies corporate, provided where necessary, by tender) to carry out specific tasks dictated by the council. Some councils have chosen to pay their elected members an allowance, as permitted under part 5 of the Local Authorities (Members' Allowances) (England) Regulations 2003.[13]

The number of councillors varies roughly in proportion to the population of the parish. Most rural parish councillors are elected to represent the entire parish, though in parishes with larger populations or those that cover large areas, the parish can be divided into wards. These wards then return a certain number of councillors each to the parish council (depending on their population). Only if there are more candidates standing for election than there are seats on the council will an election be held. However, sometimes there are fewer candidates than seats. When this happens, the vacant seats have to be filled by co-option by the council. If a vacancy arises for a seat mid-term, an election is only held if a certain number (usually ten) of parish residents request an election. Otherwise the council will co-opt someone to be the replacement councillor.

The Localism Act 2011 introduced new arrangements which replaced the 'Standards Board regime' with local monitoring by district, unitary or equivalent authorities. Under new regulations which came into effect in 2012 all parish council in England are required to adopt a code of conduct to which parish councillors must comply with and to promote and maintain high standards. The legislation also introduced a new criminal offence of failing to comply with statutory requirements. More than one 'model code' has been published and councils are free to modify an existing code or adopt a new code. In either case the code must comply with the Nolan Principles of Public Life.[14]

Status and styles

A parish can gain city status but only if that is granted by the Crown. In England, there are currently eight parishes with city status, all places with long-established Anglican cathedrals: Chichester, Ely, Hereford, Lichfield, Ripon, Salisbury, Truro and Wells.

The council of an ungrouped parish may unilaterally pass a resolution giving the parish the status of a town.[15] The parish council becomes a "town council".[16] Around 400 parish councils are called town councils.

Under the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007, a civil parish may now be given an "alternative style" meaning one of the following:

- community

- neighbourhood

- village

The chairman of a town council will have the title "town mayor" and that of a parish council which is a city will usually have the title of mayor. As a result, a parish council can also be called a town council, a community council, a village council or occasionally a city council (though most cities are not parishes but principal areas, or in England specifically metropolitan boroughs or non-metropolitan districts).[17][18]

Charter trustees

When a city or town has been abolished as a borough, and it is considered desirable to maintain continuity of the charter, the charter may be transferred to a parish council for its area. Where there is no such parish council, the district council may appoint charter trustees to whom the charter and the arms of the former borough will belong. The charter trustees (who consist of the councillor or councillors for the area of the former borough) maintain traditions such as mayoralty. An example of such a city was Hereford, whose city council was merged in 1998 to form a unitary Herefordshire. The area of the city of Hereford remained unparished until 2000 when a parish council was created for the city. The charter trustees for the City of Bath make up the majority of the councillors on Bath and North East Somerset Council.

Geography

Civil parishes cover 35% of England's population, with one in Greater London and very few in the other conurbations. Civil parishes vary greatly in size: many cover tiny hamlets with populations of less than 100, whereas some large parishes cover towns with populations of tens of thousands. Weston-super-Mare, with a population of 71,758, is the most populous civil parish. In many cases, several small villages are located in a single parish. Large urban areas are mostly unparished, as the government at the time of the Local Government Act 1972 discouraged their creation for large towns or their suburbs, but there is generally nothing to stop their establishment. For example, Birmingham has just one parish, New Frankley, whilst Oxford has four, and Northampton has seven. Parishes could not however be established in London until the changing of the law in 2007.

Deserted parishes

The 2001 census recorded several parishes with no inhabitants. These were Chester Castle (in the middle of Chester city centre), Newland with Woodhouse Moor, Beaumont Chase, Martinsthorpe, Meering, Stanground North (subsequently abolished), Sturston, Tottington, and Tyneham. The last three had been taken over by the British Armed Forces during World War II and remain deserted.

Detached parts and divided parishes

The main administrative divisions of land, divorced into secular and religious functions in the 19th century, so direct predecessors of the civil parishes are known as the 'ancient parishes'. A minority of these had detached parts: exclaves from the rest of the parish, which resulted in three possibilities, an enclave within another parish, a detached part between other parishes or pene-enclave where mostly surrounded by sea.

In some cases a detached part was in a different county. In other cases, counties had a detached part comprising a parish. Both of these cases resulted in a different representatives on the national level and different justices of the peace, sheriffs, bailiffs, churchwardens, highway wardens and constables, in the detached part to those parishes surrounding them. There were also examples in a few counties of parishes split between two or more counties such as Todmorden, split between Lancashire and Yorkshire.[19]

These anomalies were for feudal system reasons, convenient to even out or diversify the land interests of lords of the manor and overlords but inconvenient to most people, the non-nobility, whether needing to attend church for birth, marriages or death, wishing to attend church or to obtain justice, pay rates or obtain poor relief. This frequent nuisance began to be remedied nationally by Parliament (in statute) in the early 19th century in the Poor Law Reforms and was more widely but not wholly eliminated in 1844. Before civil parishes were introduced, the Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844 transferred many parishes which were detached parts of a county to the county which mostly surrounded them. The remaining detached parts of counties were transferred in the 1890s and in 1931, with one exception. A detached part of the parish of Tetworth, surrounded by Cambridgeshire was finally removed in 1965 from Huntingdonshire (as with neighbouring Rutland, the Soke of Peterborough and nearby Isle of Ely) which were downgraded from county or quasi-county status or dissolved.

Other legislation, including the Divided Parishes and Poor Law Amendment Act 1882, eliminated instances of civil parishes being split between multiple counties, and by 1901 Stanground (in Huntingdonshire and the Isle of Ely) was the sole remaining example.[20] Stanground was split into two parishes, one in each county, in 1905.[21]

As mentioned, the separation of church and state in local government in the 19th century, overlapped these consolidatory boundary reforms as they were not complete by the end of the century. The Church of England adopted similar reforms on a locally-controlled (subsidiarity), ad hoc basis and so still has a few ecclesiastical parishes with detached parts.[22]

-

Detached parts of Cowley.

-

Detached parts of Enfield.

-

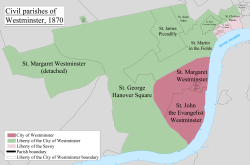

Detached parts of Westminster.

See also

References

- Wright, R S; Hobhouse, Henry (1884). An Outline of Local Government and Local Taxation in England and Wales (Excluding the Metropolis). London: W Maxwell & Son.

- ↑ Mid-2010 Population Estimates for Parishes in England and Wales

- ↑ Office for National Statistics

- ↑ Queen's Park parish council gets go-ahead BBC

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Guidance on Community Governance Reviews (PDF). London: Department for Communities and Local Government. 2010. ISBN 978-1-4098-2421-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Arnold-Baker, Charles (1989). Local Council Administration in English Parishes and Welsh Communities. Longcross Press. ISBN 978-0-902378-09-4.

- ↑ Victoria County Histories in every entry provides for most parishes, but not all, evidence of local private charities with details.

- ↑ What is a parish or town council, National Association of Local Councils website, accessed 14 August 2010

- ↑ This was ss.58-77 of bill, which received royal assent on 30 October 2007: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/pabills/200607/local_government_and_public_involvement_in_health.htm

- ↑ "Birtley Town Council – Annual Return 2005/2006". Gateshead Council. 29 September 2006.

- ↑ "The Portsmouth City Council (Reorganisation of Community Governance) Order 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Parishes and Charter Trustees in England 2011-12

- ↑ Full list of powers of parish councils - Downloadable Microsoft Word Document

- ↑ Local Government Act 2000 The Local Authorities (Members’ Allowances) (England) Regulations 2003 Reg 30

- ↑ Local government: the standards regime in England - Commons Library Standard Note, Accessed 01 May 2015

- ↑ "The council of a parish which is not grouped with any other parish may resolve that the parish shall have the status of a town""Local Government Act 1972 (c.70), Part XIII". Revised Statutes. Office of Public Sector Information. 1972. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Local government in England and Wales: A Guide to the New System. London: HMSO. 1974. p. 158. ISBN 0-11-750847-0.

- ↑ NALC - National Association of Local Councils Retrieved 26 December 2009

- ↑ Guidance on Community Governance Reviews (April 2008), London: Department for Communities and Local Government. ISBN 978-1-8511-2917-1. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ↑ Todmorden Civil Parish Council and Community website. Retrieved 2014-11-27

- ↑ 1901 Census of England and Wales, General Report: Administrative Counties and County Boroughs

- ↑ Local Government Board Order No. 56410, made under the Local Government Act 1894 (56 & 57 Vict. c.73) s.36

- ↑ Ecclesiastical parish still with detached part (example): Hascombe The Church of England. Retrieved 2014-11-27

External links

- In praise of ... civil parishes Editorial in The Guardian, 2011-05-16.

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||