Cividade de Terroso

Cividade de Terroso was an important city of the Castro culture in North-western Iberian Peninsula, located in Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal.

The city, known during the Middle Ages as Civitas Teroso (The City of Terroso), was built at the summit of Cividade Hill, in the ecclesiastical parish of Terroso, Póvoa de Varzim, less than 5 km from the coast, near the eastern edge of the modern city.

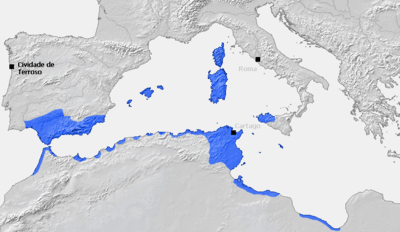

Located in the heart of the Castro region,[1] the Cividade prospered due to its strong defensive walls and its location near the ocean, which facilitated trade with the maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea. However, this trade eventually attracted Roman attention and the Cividade and the Castro culture perished at the end of the Lusitanian War, in which Rome's victory was secured through the murder of Viriathus, leader of the Lusitanians.[2]

Beyond the main Castro settlement, three of Cividade de Terroso's outposts are known: Castro de Laundos (mostly unexplored), Castro de Navais (only the fountain and site remains, as it is inhabited to this day), and Castro de Argivai (a Castro culture farmhouse, severely damaged when it was discovered).

History

The settlement of Cividade de Terroso was founded during the Bronze Age, between 800 and 900 BC, as a result of the displacement of the people inhabiting the fertile plain of Beiriz and Várzea in Póvoa de Varzim. This data is supported by the discovery of egg-shaped cesspits, excavated in 1981 by Armando Coelho, where he collected fragments of four vases of the earlier period prior to the settlement of the Cividade.[3] As such, it is part of the oldest castro settlements, such as the ones from Santa Luzia or Roriz.[4]

The Castro town maintained trade relations with the civilizations of the Mediterranean, mainly during the Carthaginian dominium in South-eastern Iberian Peninsula.[2]

During the Punic Wars, the Romans had learned of the wealth of the Castro region in gold and tin. Viriathus, who led the Lusitanian troops, hindered northward growth of the Roman Republic at the Douro river, but his murder in 138 BC opened the way for the Roman legions.

Decimus Junius Brutus led a campaign in order to annex the Castro region for Rome, which led to the complete destruction of the city,[5] just after the death of Viriathus. The deeds of the Roman commander had echoed in Rome, where he passed to be known by the title Callaicus - from Gallaecia, name by which the Romans knew the Castro region, in honour of the people they first encountered - the Callaeci in the area of Calle, around the modern city of Porto.[6]

Strabo wrote, probably describing this period: "until they were stopped by the Romans, who humiliated them and reduced most of their cities to mere villages" (Strabo, III.3.5). Some time later, the Cividade was rebuilt and became heavily Romanized, which started the castro's last urban stage.

The region was incorporated in the Roman Empire and totally pacified during the rule of Caesar Augustus. In the coastal plain, a Roman villa was created, property of a family known as the Euracini. The family was joined by Castro people that started to return to the life in the plain, and Villa Euracini was built. The fishery activity developed with the cetariæ, a Roman method of preserving fish in brine. Thus, from the 1st century onwards, and during the imperial period, the gradual abandonment of Cividade Hill started.[5]

In Memória Paroquiais (Parish Memories) of 1758, the director António Fernandes da Loba with other clergymen from the parish of Terroso, wrote: This parish is all surrounded by farming fields, and in one area, almost in the middle of it, there is a higher hill, that is about a third of the farming fields of this parish and the Ancient say that this was the City of Moors Hill, because it is known as Cividade Hill.[3]

The Lieutenant Veiga Leal in the News of Póvoa de Varzim on May 24 of 1758 wrote: "From the Hill known as Cividade, where one can see several hints of houses, that people say formed a city, to this town arrived cars with bricks from the ruins of that one."[3]

Cividade was later rarely cited by other authors. Nevertheless, in the early 20th century, Rocha Peixoto encouraged his friend António dos Santos Graça in order to subsidize archaeology works.[3]

Excavations began on June 5 of the year 1906 with 25 manual workers and continued until October of the same year, interrupted due to bad weather;[3] they recommenced in May 1907, finishing that same year. The materials discovered were taken to museums in the city of Porto.[3]

After the death of Rocha Peixoto, in 1909, some rocks of the Cividade had been used to pave some streets of Póvoa de Varzim, explicitly Rua Santos Minho Street and Rua das Hortas.[3] Occasionally, groups of scouts of the Portuguese Youth and others in the decades of 1950 and 1960, made diggings in search for archeology pieces. This was seen as archaeological vandalism, but continued even after the Cividade was listed as a property of Public Interest in 1961.[3]

In 1980, the City council of the Póvoa de Varzim invited Armando Coelho to pursue further archaeological works; these took place during the summer of that year.[3] Later, the city hall purchased the acropolis area and constructed the archaeological museum of the Cividade de Terroso in its entrance.

In 2005, groups of Portuguese and Spanish (Galician) archaeologists had started to study the hypothesis of this cividade and six others to be classified as World Heritage sites of UNESCO.[7][8]

Defensive system

The most typical characteristic of the castros is its defensive system.[4] The inhabitants had chosen to start living in the hill as a way of protection against attacks and lootings by rival tribes. The Cividade was erected at 152 metres height (about 500 feet), allowing an excellent position to monitor the entire region. One of the sides, the north, was blocked by São Félix Hill, where a smaller castro was built, the Castro de Laundos, that served as a surveillance post.

The migrations of Turduli and Celtici proceeding from the South of the Iberian Peninsula heading North are referred by Strabo and were the reason for the improvement of the defensive systems of the castros around 500 BC.

Cividade de Terroso is one of the most heavily defensive castros, given that the acropolis was surrounded by three rings of walls. These walls were built at different stages, due to the growth of the town.

The walls had great blocks without mortar and were adapted to the hill's topography. The areas of easier access (South, East and West) possessed high, wide and resistant walls; while the ones in land with steep slopes were protected mainly by strengthening the local features.

That can easily be visible with the discovered structures in the East that present a strong defensive system that reaches 5.30 metres (17 feet 5 inches) wide. While in the Northeast, the wall was constructed using natural granite that only was crowned by a wall of rocks.

The entrance that interrupted the wall was paved with flagstone with about 1.70 metres (5 feet 7 inches) of width. The defensive perimeter seems to include a ditch of about 1 metre (3 feet 3 inches) of depth and width in base of the hill, as it was detected while a house was being built in the north of the hill.

Urban structure

In the area, within the three rings of walls, in the acropolis, diverse types of ruins exists, especially the funerary enclosures, which are extremely rare in the Castro culture world.

In the archaeological works carried through the beginning of 20th century, the Cividade seemed to have a disorganized structure, but more recent data suggests instead an organization whose characteristics stem from older levels of occupation, which had been ignored during the first archaeological works.

Each one of the quadrants of the town is divided in nuclei around a family square almost always paved with flagstone. Some houses possessed a forecourt.

At its peak, the town would enclose nearly 12 hectares (30 acres) and was inhabited by several hundred people.

Stages

The Cividade had urbanization stages: during the first centuries, the small habitations were built with vegetable elements mixed with adobe.

The first stonework started in the 5th century B.C.,[3] this became possible due to the iron peaks technology. A technology that was only available in Asia Minor, but that was brought to the Iberian Peninsula by Phoenician settlers in the Atlantic Coast during the 8th and 7th centuries B.C.[4]

Buildings during this period are, characteristically, circular with diameters between 4 and 5 meters and with walls 30 to 40 cm thick. The granite rocks were fractured or splintered, and placed in two lines, with the smoothest part heading for the exterior and interior of the house. The space between the two rocks was filled with small rocks and mortar of large sand-grains creating robust walls.

In the last stage, the Roman one (starting in 138 – 136 B.C.), following the destruction by Decimus Junius Brutus, there is an urban reorganization with use of the new building techniques and change in shapes and sizes. Quadrangular structures started appearing, replacing the typical Castro culture circular architecture. The roof started being made out of "tegula" instead of vegetable material with adobe.[3]

During this stage, stonework used in home construction were quadrangular; the project of two stone alignments remained, but rooms were wider and filled with large sand-grains or adobe and rocks of small to average size, resulting in thicker walls with 45–60 cm.[3]

Family settings

The family settings, having four or five circular divisions,[4] encircle a flagstone paved yard where the doors of the different divisions converged. These central yards had an important role in family life as the area where the daily family activities took place. These nuclei would be closed by key, granting privacy to families.[3]

The building interiors of the second stage, prior to the Roman period, possessed fine floors made of adobe or large sand-grains. Some of these floors were decorated with rope-styled, wave and circle carvings and motifs, especially in fireplaces. In the Roman-influence stage, these floors had become well-taken care of, being denser and thicker.

Streets

The family settings were divided by narrow roads with some public spaces. The two main streets had the typical Roman orientation of the Decumanus and Cardium.[3]

The Decumanus was a street that slightly followed the wall to the East for the West and slightly curved for Southwest from the crossroad with the Cardium (North-South street), finishing in the entrance of the Cividade. The exterior access was fulfilled by a slight descending reaching the way that is still used today to enter in the town.[3]

These main roads divided the settlement in four parts. Each one of these parts had four or five family settings.[3]

In some areas of the city, vestiges of sewers or narrow channels had been discovered; these could have been used to channel rain water.[3]

Culture

The population worked in agriculture, namely cereals and horticulture, fishing, recollection, shepherding and worked metals, textiles and ceramics. Cultural influences arrived from the inland Iberian Peninsula, beyond the ones proceeding from the Mediterranean through trade.[9]

The Castro culture is known by having defensive walls in their cities and villages, with circular houses in hilltops and for its characteristic ceramics, widely popular among them. It disappears with the Roman acculturation and the movement of the populations for the coastal plain, where the strong Roman cultural presence, from the 2nd century BC onwards, is visible in the vestiges of Roman villas found there where, currently, the city of the Póvoa de Varzim is located (Old Town of Póvoa de Varzim, Alto de Martim Vaz and Junqueira), and in the parishes of Estela (Villa Mendo) and near the Chapel of Santo André in Aver-o-Mar.

Feeding

The population lived mainly from agriculture, mainly with the culture of cereals such as wheat and barley, and of vegetables (the broadbean) and acorn.

The concheiro found in the Cividade showed that they ate raw or coocked limpets, mussels and Sea urchins.[4] These species are still broadly common. Fishing must not have been a regular activity, given the lack of archaeological evidence, but the discovery of hooks and net weights showed that the Castro people were able to catch fish of considerable size such as grouper and snook.[9]

Barley was farmed to produce a kind of beer, which was nicknamed zythos. Beer was considered a barbaric drink by the Greeks and Romans given the fact that they were accustomed to the subtleness of wine. Acorn was smashed to create a kind of flour.[9]

Pickings wild plants, fruits, seeds and roots complemented the dietary staple; they also ate and picked wild blackberries, dandelion, clovers and even kelps. Some of these vegetables are still used by the local population today. The Romans introduced the consumption of wine and olive oil.[9]

The animals used by the Castro people are confirmed by classic documents and archaeological registers, and included horses, pigs, cows and sheep. It is interesting to note that there was a cultural taboo against the eating of horses or dogs.[9]

There is little evidence of poultry during the Castro period, but during the period of Roman influence it became quite common.[9]

Although there is only fragmentary evidence in the Cividade, hunting must have been a part of everyday life given that classic sources, such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder describe the region as very rich in fauna, including: wild bear, deer, wild boars, foxes, beavers, rabbits, hares and a variety of birds; all of which would have been valuable food sources.[9]

Handicrafts

Castro ceramics (goblets and vases) evolved during the ages, from a primitive system to the use of potter's wheels. However, the amphorae and the use of the glass only started to be common with the Romanization. These amphorae, essentially, served for the transport and storage of cereals, fruits, wine and olive oil.[9]

Many of the ceramics found in the Cividade de Terroso had local characteristics.[9] Pottery was seen as a man's work and significant amounts were found with great variety, showing that it was a cheap, important and accessible product.

However, the city's ceramic structure are practically identical to the ones found in other castros of the same period. The decoration of the vases was of the incisive type (decoration cut into the clay before firing), but scapulae and impressed vases also existed; adobe lace, in rope form, with or without incisions are also found.[9]

Drawings in "S", assigned as palmípedes, are frequently found in engraved vases, these could be printed with other printed or engraved drawings. Other decorative forms, that can appear mixed and with diverse techniques, include circles, triangles, semicircles, lines, in zig-zag, in a total of about two hundred of different kinds of drawings.[9]

Weaving was sufficiently generalized and was seen as a woman's duty and was also progressing, especially during the Roman period; some weights of sewing press were found and sets of ten of cossoiros. The discovery of shears strengthened the idea of the systematic breeding of sheep to use their wool.[9]

Numerous vestiges of metallurgic activities had been detected and great amounts of casting slags, fibulae, fragmented iron objects and other metals remains were discovered, mostly lead, copper/bronze, tin and perhaps gold. Gatos (for repairing ceramics), pins, fibulae, stili and needles in copper or bronze, demonstrating that the work in copper and its alloys was one of the most common activities of the town. The iron was used for many every-day objects, some nails were found, but also hooks and a tip of a scythe or dagger.[9]

Near the door of the wall (in the southwest of the city) a workshop was identified, given that in the place some vestiges of this activity had been found such as the use of fire with high temperatures, nugget and slags for casting metals, ores and other indications.[9]

Goldsmithery contributed for Póvoa de Varzim being a reference for proto-historical archaeology in North-western Iberian Peninsula. Namely, with the finding of some complete jewellery: the Earrings of Laundos and the articulated necklace and earrings of Estela. In the proper Cividade, some certifications of works in gold and silver had been collected by Rocha Peixoto. In all the mountain range of Rates, the ancient mining explorations are visible: Castro and Roman ones, given that these hills possessed the essential gold and silver used for jewellery production.

In 1904, a mason while building a mill in the top of São Félix Hill, in the vicinity of the smaller Castro de Laundos, found a vase with jewellery inside, these pieces had been bought by Rocha Peixoto that took them to the Museum of Porto. The jewellery was made using an evolved technique, very similar to ones made in the Mediterranean, namely with the use of plates and welds, filigree and granulated.

Religion and death rituals

Religious cults and ceremonies had the objective to harmonize the people with natural forces. The Castro people had a great number of deities, but in the coastal area where the city is located, Cosus, a native deity related in later periods to the Roman god Mars, prevailed to such an extent that no other deities popular in the hinterland were venerated in the coastal region where Cosus was worshiped.[10]

Some cesspits, for instance organized as a pentagon, adorn the flagstone of the Cividade, their function is unknown, but may have had some magical-religious function.[11]

The funerary ritual of the Cividade was probably common to other pre-Roman peoples of the Portuguese territory, but archaeological data are very rarely found in the Castro area, excepting at Cividade de Terroso.[11]

The ritual of the Cividade was the rite of cremation and placing the ashes of their dead in small circular-shaped cesspits with stonework adornment in the interior of the houses. In later periods, the ashes were deposited in the exterior of the houses, but still inside of the family setting.[11]

In 1980, the discovery of a funerary cist, and an entire vase, and fragments of another one without covering, evidences breaking. This vase was very similar to another found in Mount São Félix, this last one with jewels in its interior, assuming that these jewels had the same funerary context.[11]

Trade

The visits of Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, and Romans had as objective the exchange of fabrics and wine for gold and tin, despite the scarcity of terrestrial ways, this was not a problem for Cividade de Terroso that was strategically located close to the sea and the Ave River, thus an extensive commerce existed via the Atlantic and river routes. However, one land route was known, the Silver Way (as named in the Roman Era) that started in the south of the peninsula reaching the northeast over land.[12]

The external commerce, dominated by tin, was complemented with domestic commerce in tribal markets between the different cities and villages of the Castro culture, they exchanged textiles, metals (gold, copper, tin and lead) and other objects including exotic products, such as glass or exotic ceramics, proceeding from contacts with the peoples of the Mediterranean or other areas of the Peninsula.

With the annexation of the Castro region by the Roman Republic, the commerce starts to be one of the main ways for regional economic development, with the Roman merchants organized in associations known as collegia. These associations functioned as true commercial companies who looked for monopoly in commercial relations.[12]

Museum facility

In the entrance of the town there is a small museum with facilities that are intended only to support the visit to the Cividade itself, such as pictures, representations and public toilets. It is a small extension of the Ethnography and History Museum of Póvoa de Varzim, located in Póvoa de Varzim City Center, where the most relevant artifacts are kept. Although the city is protected by fences and a gate near the museum, the entrance to the city is free.

References

- ↑ Armando Coelho Ferreira da Silva A Cultura Castreja no Noroeste de Portugal Museu Arqueológico da Citânia de Sanfins, 1986

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Flores Gomes, José Manuel & Carneiro, Deolinda: Subtus Montis Terroso. CMPV (2005), "Introdução", p.12

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 Flores Gomes, José Manuel & Carneiro, Deolinda: Subtus Montis Terroso. CMPV (2005), "Cultura castreja - A Cividade de Terroso", pp.97-131

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Póvoa de Varzim, Um Pé na Terra, Outro no Mar

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Flores Gomes, José Manuel & Carneiro, Deolinda: Subtus Montis Terroso CMPV (2005), "Origens do Povoamento" pp.74-76

- ↑ Roteiro Arqueológico do Eixo Atlântico

- ↑ Casa de Sarmento - Centro de Estudos do Património

- ↑ Arqueologia - Candidatura apresentada - São seis os Castros a património mundial - correiodamanha.pt

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 Flores Gomes, José Manuel & Carneiro, Deolinda: Subtus Montis Terroso. CMPV (2005), "Economia e ergologia", pp.133-187

- ↑ Pedreño, Juan Carlos Olivares (11 November 2005). "Celtic Gods of the Iberian Peninsula" (PDF) 6. Guimarães, Portugal: E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. pp. 607–649. ISSN 1540-4889.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Flores Gomes, José Manuel & Carneiro, Deolinda: Subtus Montis Terroso. CMPV (2005), "Religiosidade: Ritos funerários e Enterramentos", pp.187-191

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Autarcia e Comércio em Bracara Augusta no período Alto-Imperial

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cividade de Terroso. |

- João Aguiar - Uma Deusa na Bruma, Edições Asa - Historical novel about the Cividade de Terroso (Póvoa de Varzim)