Christopher La Farge (author)

| Christopher Grant La Farge | |

|---|---|

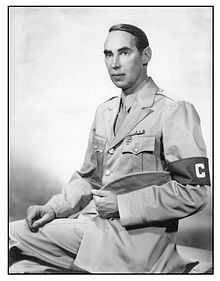

Christopher Grant La Farge in uniform as a war correspondent during World War II. | |

| Born |

December 10, 1897 New York City, United States |

| Died |

January 5, 1956 (aged 58) Providence, Rhode Island, United States |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | verse novel |

Christopher Grant La Farge was an American novelist and poet known for writing verse novels that chronicled life in Rhode Island.

Early life and education

Christopher Grant La Farge was born in New York City the son of the architect Christopher Grant LaFarge and Florence Bayard Lockwood LaFarge. His paternal grandfather was the painter and stained-glass artist John La Farge and his younger brother Oliver Hazard Perry also became a novelist. He grew up in New York City and in Saunderstowon, Rhode Island, and later moved to the family farm (named The River Farm) near Saunderstown, which was given to him by his father. He attended St. Bernard's School (New York) and Groton School (Massachusetts).

La Farge, known as "Kipper" to friends and family, enrolled in Harvard College in 1915, but his college career was interrupted by World War I. After reserve officer training in Plattsburg, NY, in 1916 and in 1918, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the cavalry. Discharged after four months in France, he returned to college. While at Harvard, he was an editor for the Harvard Advocate literary magazine. He graduated from Harvard with a B.A. in 1920 and went on to complete a B.S. from the School of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania in 1923.

In June 1923, he married Louisa Ruth Hoar (born 1898), daughter of Congressman Rockwood Hoar of Massachusetts and stepdaughter of Congressman Frederick H. Gillett. President and Mrs. Warren G. Harding attended the wedding.[1] They had two children: the cardiologist Christopher Grant Champlin LaFarge (born 1928) and the writer William Ellis Rice “WER” LaFarge. Louisa died of cancer in 1945, and in 1946 LaFarge married Violet Amory Loomis (born 1918), with whom he had a son, the writer Thomas Sargeant LaFarge. With this marriage, he also gained two stepchildren, William Farnsworth Loomis and Joan Loomis.

Architectural career

From 1924 to 1931, La Farge worked as a designer for the New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White. During this period, he also exhibited his watercolors at such New York art galleries as Ferargil (1930) and Wildenstein (1931). Following the success of his brother Oliver’s novel about Navajo Indian life, Laughing Boy, LaFarge worked with his father on exhibits of Native American arts at the Brooklyn Museum. In 1931, he left McKim, Mead & White to join his father’s architectural firm of LaFarge, Warren, and Clark (later renamed La Farge and Son). In 1933, he designed a monument to the Jesuit missionary Andrew White in Maryland near St. Mary's City.[2] However, the Great Depression drove the firm out of business, and LaFarge abandoned architecture as a career.

Writing career

In 1932, La Farge moved his family to Kent, England, where he wrote his first novel, Hoxsie Sells His Acres (1934), a verse chronicle about a Rhode Island landowner who decides to sell his farmland for development. La Farge’s goal in writing his novel in verse was to "make this a comprehensible form as interesting as the novel in prose and more moving."[3] In 1934, he moved back to the United States, where he split his time between Rhode Island and New York. Several of his subsequent books were also set in Rhode Island, and he became known as a skillful observer of this region. He also began contributing stories and poems to magazines like the New Yorker, The American, Harper's, and the Saturday Review of Literature.

His second novel, Each to the Other (1939), was also written in verse. Its plot revolved around the domestic difficulties of a father and a son, and at least one reviewer saw in it reflections of La Farge’s own life.[3] It was a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection and won the Benson Silver medal of the London Royal Society of Literature. La Farge's third novel, The Sudden Guest (1946, written in prose), was likewise a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection. Set in Rhode Island, its central character is an unpleasant old woman who reminisces about the great New England Hurricane of 1938 as she prepares for the arrival of another hurricane. With its acutely observed protagonist—self-righteous, rigid, and anti-Semitic—the story forms a parable intended to remind Americans of the cost of isolationism. It was LaFarge’s most successful book, selling more than half a million copies. His last verse novel, Beauty for Ashes (1953), was a novel of relationships revolving around a beautiful young woman and three men in rural Rhode Island.

During World War II, La Farge was an active member of the Authors' League of America and the Writers' War Board.[4] In 1943, Harper's magazine sent him to the South Pacific as a war correspondent. "His intention," wrote Newsweek, "was to report the war not with named and dated facts, but deliberately in the form of fiction."[3] The stories he wrote on this assignment were later published together under the title East by Southwest (1944). La Farge published two other volumes of short stories, many of which had previously appeared in the New Yorker. In 1941, he collected ten stories he had written about a single family under the title The Wilsons; his first work in prose, it was described as a "wicked and graceful...study of American snobbism."[3] And in 1949, he reprinted seventeen of his favorite stories, with prefatory comments, as All Sorts and Kinds (1949).

La Farge’s one published play, Mesa Verde (1945), was originally conceived as an opera libretto and is notable for including Navajo speech and phraseology. Coward-McCann, his publisher, printed a collection of his poetry, Poems and Portraits, in 1940. La Farge wrote occasional book reviews and articles, as well, such as a 1954 analysis of the reactionary elements in Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer novels.[5]

La Farge was one of a group of high-profile writers including Pearl Buck, Clifton Fadiman, Upton Sinclair, and John Dos Passos who came together in 1945 to found a new, cooperative, ad-free magazine that would be owned and controlled by writers and artists. The first issue of this short-lived publication came out in 1947 under the title '47, the Magazine of the Year.[6]

La Farge died suddenly of a stroke in Providence, Rhode Island, having just started another novel in verse. Many of his letters and manuscripts are held in the collections of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, New York Public Library, University of Buffalo, University of Chicago, and Yale and Harvard universities. His diaries are housed at the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Publications

Books

- Beauty for Ashes, Coward-McCann, 1953 (verse novel)

- All Sorts and Kinds, Coward-McCann, 1949 (short stories)

- The Sudden Guest, Coward-McCann, 1946 (novel)

- Mesa Verde, 1945 (verse play)

- East by Southwest, Coward-McCann, 1944 (short stories)

- Poems and Portraits, Coward-McCann, 1940 (verse)

- The Wilsons Coward-McCann, 1940 (short stories)

- Each to the Other, 1939 (verse novel)

- Hoxsie Sells His Acres, 1934 (verse novel)

Articles

- "Soldier into Civilian," Harper's, March 1945.

- “Mickey Spillane and His Bloody Hammer,” The Saturday Review, Nov. 6, 1954.

References

- ↑ "The President and Mrs. Harding Attend Miss Hoar's Wedding". Chicago Daily Tribune, June 19, 1923, p. 23.

- ↑ LaFarge, John, S.J. The Manner Is Ordinary. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1954, pp. 217-18.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Christopher Grant La Farge." Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 6: 1956–1960. American Council of Learned Societies, 1980.

- ↑ Laskin, Franklin T. "All Rights Reserved: The Author's Lost Property in Publishing and Entertainment." Copyright L. Symp. Vol. 7. 1956.

- ↑ Whiting, Frederick. "Bodies of Evidence: Post-War Detective Fiction and the Monstrous Origins of the Sexual Psychopath." Yale Journal of Criticism 18:1 (2005), pp. 149-178.

- ↑ Ellison, Jerome. "When Howells' Pipedream Came True." The New England Quarterly, 42:2 (1969), pp. 253-260.