Christianity in the 6th century

.png)

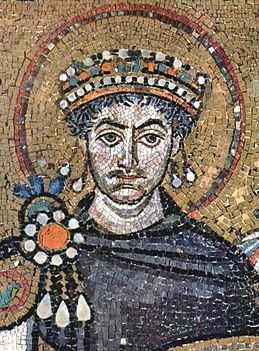

In 6th century Christianity, Roman Emperor Justinian launched a military campaign in Constantinople to reclaim the western provinces from the Arian Germans, starting with North Africa and proceeding to Italy. Though he was temporarily successful in recapturing much of the western Mediterranean he destroyed the urban centers and permanently ruined the economies in much of the West. Rome and other cities were abandoned. In the coming centuries the Western Church, as virtually the only surviving Roman institution in the West, became the only remaining link to Greek culture and civilization.

In the East, Roman imperial rule continued through the period historians now call the Byzantine Empire. Even in the West, where imperial political control gradually declined, distinctly Roman culture continued long afterwards; thus historians today prefer to speak of a "transformation of the Roman world" rather than a "Fall of Rome." The advent of the Early Middle Ages was a gradual and often localised process whereby, in the West, rural areas became power centres whilst urban areas declined. Although the greater number of Christians remained in the East, the developments in the West would set the stage for major developments in the Christian world during the later Middle Ages.

Second Council of Constantinople

Prior to the Second Council of Constantinople was a prolonged controversy over the treatment of three subjects, all considered sympathetic to Nestorianism, the heresy that there are two separate persons in the Incarnation of Christ.[1] Emperor Justinian condemned the Three Chapters, hoping to appeal to monophysite Christians with his anti-Nestorian zeal.[2] Monophysites believe that in the Incarnate Christ there is one nature, not two.[3] Eastern patriarchs supported the emperor, but in the West his interference was resented, and Pope Vigilius resisted his edict on the grounds that it opposed the Chalcedonian decrees.[2] Justinian's policy was in fact an attack on Antiochene theology and the decisions of Chalcedon.[2] The pope assented and condemned the Three Chapters, but protests in the West caused him to retract his condemnation.[2] The emperor called the Second Council of Constantinople to resolve the controversy.[2]

The council met in Constantinople in 553, and it has since become recognized as the fifth of the first seven Ecumenical Councils. The council condemned certain Nestorian writings and authors. This move was instigated by Emperor Justinian in an effort to conciliate the monophysite Christians, it was opposed in the West, and the popes' acceptance of the council caused a major schism.[4]

The council interpreted the decrees of Chalcedon and further explained the relationship of the two natures of Jesus; it also condemned the teachings of Origen on the pre-existence of the soul, and Apocatastasis. The council, attended mostly by Eastern bishops, condemned the Three Chapters and, indirectly, the Pope Vigilius.[2] It also affirmed the East's intention to remain in communion with Rome.[2]

Vigilius declared his submission to the council, as did his successor, Pelagius I.[2] The council was not immediately recognized as ecumenical in the West, and the churches of Milan and Aquileia even broke off communion with Rome over this issue.[4] The schism was not repaired until the late 6th century for Milan and the late 7th century for Aquileia.[4]

Eastern Church

In the 530s the second Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) was built in Constantinople under Justinian. The first church was destroyed during the Nika riots. The second Hagia Sophia became the center of the ecclesiastical community for the rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium.

Western theology before the Carolingian Empire

When the Western Roman Empire fragmented under the impact of various 'barbarian' invasions, the Empire-wide intellectual culture that had underpinned late Patristic theology had its interconnections cut. Theology tended to become more localised, more diverse, more fragmented. The classic Christianity preserved in Italy by men like Boethius and Cassiodorus was different from the vigorous Frankish Christianity documented by Gregory of Tours, which was different from the Christianity that flourished in Ireland and Northumbria. Throughout this period, theology tended to be a more monastic affair, flourishing in monastic havens where the conditions and resources for theological learning could be maintained.

Important writers include:

- Caesarius of Arles (c.468-542)

- Boethius (480-524)

- Cassiodorus (c.480-c.585)

- Pope Gregory I (c.540-604)

Gregory the Great

Saint Gregory I the Great was pope from September 3, 590 until his death. He is also known as Gregorius Dialogus (Gregory the Dialogist) in Eastern Orthodoxy because of the Dialogues he wrote. He was the first of the popes from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the four great Latin Fathers of the Church. Of all popes, Gregory I had the most influence on the early medieval church.[5]

Monasticism

Benedict

Benedict of Nursia is the most influential of Western monks. He was educated in Rome but soon sought the life of a hermit in a cave at Subiaco, outside the city. He then attracted followers with whom he founded the monastery of Monte Cassino around 520, between Rome and Naples. In 530, he wrote his Rule of St Benedict as a practical guide for monastic community life. Its message spread to monasteries throughout Europe.[6] Monasteries became major conduits of civilization, preserving craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria and libraries. They functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers as well as a focus for spiritual life.[7]

During this period the Visigoths and Lombards moved away from Arianism for Catholicism.[8] Pope Gregory I played a notable role in these conversions and dramatically reformed the ecclesiastical structures and administration which then launched renewed missionary efforts.[9]

Little is known about the origins of the first important monastic rule (Regula) in Western Europe, the anonymous Rule of the Master (Regula magistri), which was written somewhere south of Rome around 500. The rule adds legalistic elements not found in earlier rules, defining the activities of the monastery, its officers, and their responsibilities in great detail.

Ireland

Irish monasticism maintained the model of a monastic community while, like John Cassian, marking the contemplative life of the hermit as the highest form of monasticism. Saints' lives frequently tell of monks (and abbots) departing some distance from the monastery to live in isolation from the community.

Irish monastic rules specify a stern life of prayer and discipline in which prayer, poverty, and obedience are the central themes. Yet Irish monks did not fear pagan learning. Irish monks needed to learn Latin, which was the language of the Church. Thus they read Latin texts, both spiritual and secular. By the end of the 7th century, Irish monastic schools were attracting students from England and from Europe. Irish monasticism spread widely, first to Scotland and Northern England, then to Gaul and Italy. Columba and his followers established monasteries at Bangor, on the northeastern coast of Ireland, at Iona, an island north-west of Scotland, and at Lindisfarne, which was founded by Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona, at the request of King Oswald of Northumbria.

Columbanus, an abbot from a Leinster noble family, traveled to Gaul in the late 6th century with twelve companions. Columbanus and his followers spread the Irish model of monastic institutions established by noble families to the continent. A whole series of new rural monastic foundations on great rural estates under Irish influence sprang up, starting with Columbanus's foundations of Fontaines and Luxeuil, sponsored by the Frankish King Childebert II. After Childebert's death Columbanus traveled east to Metz, where Theudebert II allowed him to establish a new monastery among the semi-pagan Alemanni in what is now Switzerland. One of Columbanus' followers founded the monastery of St. Gall on the shores of Lake Constance, while Columbanus continued onward across the Alps to the kingdom of the Lombards in Italy. There King Agilulf and his wife Theodolinda granted Columbanus land in the mountains between Genoa and Milan, where he established the monastery of Bobbio.

Spread of Christianity

As the political boundaries of the Western Roman Empire diminished and then collapsed, Christianity spread beyond the old borders of the empire and into lands that had never been Romanised. The Lombards adopted Catholicism as they entered Italy.

Irish missionaries

Although Ireland had never been part of the Roman Empire, Christianity had come there and developed, largely independently from Celtic Christianity. Christianity spread from Roman Britain to Ireland, especially aided by the missionary activity of Saint Patrick. Patrick had been captured into slavery in Ireland, and following his escape and later consecration as bishop, he returned to the isle to bring them the Gospel.

The Irish monks had developed a concept of peregrinatio.[10] This essentially meant that a monk would leave the monastery and his Christian country to proselytize among the heathens, as self-chosen punishment for his sins. Soon, Irish missionaries such as Columba and Columbanus spread this Christianity, with its distinctively Irish features, to Scotland and the continent. From 590 onwards Irish missionaries were active in Gaul, Scotland, Wales and England.

Anglo-Saxon Britain

Although southern Britain had been a Roman province, in 407 the imperial legions left the isle, and the Roman elite followed. Some time later that century, various barbarian tribes went from raiding and pillaging the island to settling and invading. These tribes are referred to as the "Anglo-Saxons", predecessors of the English. They were entirely pagan, having never been part of the empire, and although they experienced Christian influence from the surrounding peoples, they were converted by the mission of St. Augustine sent by Pope Gregory I.

Franks

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of Gaul (modern France) were overrun by Germanic Franks in the early 5th century. The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish King Clovis I converted from paganism to Roman Catholicism in 496. Clovis insisted that his fellow nobles follow suit, strengthening his newly established kingdom by uniting the faith of the rulers with that of the ruled.

The Germanic peoples underwent gradual Christianization in the course of the Early Middle Ages, resulting in a unique form of Christianity known as Germanic Christianity. The East and West Germanic tribes were the first to convert through various means. However, it was not until the 12th century that the North Germanic tribes had Christianized.

In the polytheistic Germanic tradition it was even possible to worship Jesus next to the native gods like Wodan and Thor. Before a battle, a pagan military leader might pray to Jesus for victory, instead of Odin, if he expected more help from the Christian God. Clovis had done that before a battle against one of the kings of the Alamanni, and had thus attributed his victory to Jesus. Such utilitarian thoughts were the basis of most conversions of rulers during this period.[11] The Christianization of the Franks lay the foundation for the further Christianization of the Germanic peoples.

Arabia

Cosmas Indicopleustes, navigator and geographer of the 6th century, wrote about Christians, bishops, monks, and martyrs in Yemen and among the Himyarites. In the 5th century a merchant from Yemen was converted in Hira, in the northeast, and upon his return led many to Christ.

Tibet

It is unclear when Christianity reached Tibet, but it seems likely that it had arrived there by the 6th century. The ancient territory of the Tibetans stretched farther west and north than the present-day Tibet, and they had many links with the Turkic and Mongolian tribes of Central Asia. It seems likely that Christianity entered the Tibetan world around 549, the time of a remarkable conversion of the White Huns. A strong church existed in Tibet by the 8th century.

Carved into a large boulder at Tankse, Ladakh, once part of Tibet but now in India, are three crosses and some inscriptions. The rock dominates the entrance to the town, on one of the main ancient trade routes between Lhasa and Bactria. The crosses are clearly of the Church of the East, and one of the words, written in Sogdian, appears to be "Jesus". Another inscription in Sogdian reads, "In the year 210 came Nosfarn from Samarkhand as emissary to the Khan of Tibet". It is possible that the inscriptions were not related to the crosses, but even on their own the crosses bear testimony to the power and influence of Christianity in that area.

- 508 - Philoxenus of Mabug begins translation of the Bible into Syriac[12]

- 524 Boethius, Roman Christian philosopher, wrote: "Theological Tractates", Consolation of Philosophy; (Loeb Classics) (Latin)

- 525 Dionysius Exiguus defines Christian calendar (AD.)

- 527 Fabius Planciades Fulgentius

- 529 - Benedict of Nursia destroys pagan temple at Monte Cassino (Italy and builds a monastery[13]

- 530 Antipope Dioscorus, possibly a legitimate Pope

- 530 Rule of St Benedict, St. Benedict founds the Benedictines

- 535 - The Hephthalite Huns - nomads living in northern China and Central Asia, who were also known as the White Huns - are taught to read and write by Nestorian missionaries.

- 535-536 Unusual climate changes recorded

- 537-555 Pope Vigilius, involved in death of Pope Silverius, conspired with Justinian and Theodora, on April 11, 548 issued Judicatum supporting Justinian's anti-Hypostatic Union, excommunicated by bishops of Carthage in 550

- 541-542 Plague of Justinian

- 542 - Julian (or Julianus) from Constantinople begins evangelizing Nubia, accompanied by an Egyptian named Theodore[14]

- 543 Justinian condemns Origen, disastrous earthquakes hit the world

- 544 Justinian condemns the Three Chapters of Theodore of Mopsuestia (died 428) and other writings of Hypostatic Union Christology of Council of Chalcedon

- 550 St. David converts Wales, crucifix introduced

- 553 Second Council of Constantinople, 5th ecumenical, called by Justinian

- 556-561 Pope Pelagius I, selected by Justinian, endorsed Judicatum

- 563 Columba goes to Scotland to evangelize Picts, establishes monastery at Iona

- 563 - Columba sails from Ireland to Scotland where he founds an evangelistic training center on Iona[15]

- 567 Cassiodorus

- 569 - Longinus, church leader in Nobatia, evangelizes Alodia (in what is now Sudan)

- 578 - Conversion to Christianity of An-numan III, last of Lachemids (Arab princes)

- 589 Third Council of Toledo, Reccared and the Visigoths convert from Arianism to Catholicism and Filioque clause is added to Nicene Creed of 381

- 590-604 Pope Gregory the Great, whom many consider the greatest pope ever, reforms church structure and administration and establishes Gregorian Chant, Seven deadly sins ...

- 592 - Death of Celtic/Irish missionary Moluag (Old Irish: Mo-Luóc)

- 591-628 Theodelinda, Queen of the Lombards, began gradual conversion from Arianism to Catholicism

- 596 St. Augustine of Canterbury sent by Pope Gregory to evangelise the Jutes

- 596 - Gregory the Great sends Augustine and a team of missionaries to (what is now) England to reintroduce the Gospel. The missionaries settle in Canterbury and within a year baptize 10,000 people[16]

- 600? Evagrius Scholasticus, Church History of AD431-594

- 600 - First Christian settlers in Andorra (southwestern Europe, between France and Spain)

See also

- History of Christianity

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- History of Christian theology

- History of Oriental Orthodoxy

- Church Fathers

- List of Church Fathers

- Christian monasticism

- Patristics

- Development of the New Testament canon

- Christianization

- History of Calvinist-Arminian debate

- Timeline of Christianity

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church

- Chronological list of saints in the 6th century

Notes and references

- ↑ "Nestorianism" and "Three Chapters." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 "Three Chapters." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ "Monophysitism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Constantinople, Second Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ↑ Pope St. Gregory I at about.com

- ↑ Woods, How the Church Built Western Civilization (2005), p. 27

- ↑ Le Goff, Medieval Civilization (1964), p. 120

- ↑ Le Goff, Medieval Civilization (1964), p. 21

- ↑ Duffy, Saints and Sinners (1997), pp. 50–52

- ↑ Padberg, Lutz v. (1998), p.67

- ↑ Padberg, Lutz v. (1998), p.48

- ↑ Price, Ira Maurice. The Ancestry of Our English Bible. Harper, 1956, p. 193.

- ↑ Latourette, 1953, p. 333

- ↑ Anderson, p. 347

- ↑ Gailey, p. 41

- ↑ Neill, pp. 58-59; Tucker, 46

Further reading

- Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. The Christian Tradition: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). University of Chicago Press (1975). ISBN 0-226-65371-4.

- Lawrence, C. H. Medieval Monasticism. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. ISBN 0-582-40427-4

- Trombley, Frank R., 1995. Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370-529 (in series Religions in the Graeco-Roman World) (Brill) ISBN 90-04-09691-4

- Fletcher, Richard, The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD. London 1997.

- Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, book 1, chp.19

- Socrates, Ecclesiastical History, book 3, chp. 1

- Mingana, The Early Spread of Christianity in Central Asia and the Far East, pp. 300.

- A.C. Moule, Christians in China Before The year 1550, pp. 19–26

- P.Y. Saeki, The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China and The Nestorian Monument in China, pp. 27–52

- Philostorgius, Ecclesiastical History.