Choice function

A choice function (selector, selection) is a mathematical function f that is defined on some collection X of nonempty sets and assigns to each set S in that collection some element f(S) of S. In other words, f is a choice function for X if and only if it belongs to the direct product of X.

An example

Let X = { {1,4,7}, {9}, {2,7} }. Then the function that assigns 7 to the set {1,4,7}, 9 to {9}, and 2 to {2,7} is a choice function on X.

History and importance

Ernst Zermelo (1904) introduced choice functions as well as the axiom of choice (AC) and proved the well-ordering theorem,[1] which states that every set can be well-ordered. AC states that every set of nonempty sets has a choice function. A weaker form of AC, the axiom of countable choice (ACω) states that every countable set of nonempty sets has a choice function. However, in the absence of either AC or ACω, some sets can still be shown to have a choice function.

- If

is a finite set of nonempty sets, then one can construct a choice function for

is a finite set of nonempty sets, then one can construct a choice function for  by picking one element from each member of

by picking one element from each member of  This requires only finitely many choices, so neither AC or ACω is needed.

This requires only finitely many choices, so neither AC or ACω is needed.

- If every member of

is a nonempty set, and the union

is a nonempty set, and the union  is well-ordered, then one may choose the least element of each member of

is well-ordered, then one may choose the least element of each member of  . In this case, it was possible to simultaneously well-order every member of

. In this case, it was possible to simultaneously well-order every member of  by making just one choice of a well-order of the union, so neither AC nor ACω was needed. (This example shows that the well-ordering theorem implies AC. The converse is also true, but less trivial.)

by making just one choice of a well-order of the union, so neither AC nor ACω was needed. (This example shows that the well-ordering theorem implies AC. The converse is also true, but less trivial.)

Refinement of the notion of choice function

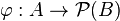

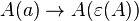

A function  is said to be a selection of a multivalued map φ:A → B (that is, a function

is said to be a selection of a multivalued map φ:A → B (that is, a function  from A to the power set

from A to the power set  ), if

), if

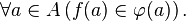

The existence of more regular choice functions, namely continuous or measurable selections is important in the theory of differential inclusions, optimal control, and mathematical economics.[2]

Bourbaki tau function

Nicolas Bourbaki used epsilon calculus for their foundations that had a  symbol that could be interpreted as choosing an object (if one existed) that satisfies a given proposition. So if

symbol that could be interpreted as choosing an object (if one existed) that satisfies a given proposition. So if  is a predicate, then

is a predicate, then  is the object that satisfies

is the object that satisfies  (if one exists, otherwise it returns an arbitrary object). Hence we may obtain quantifiers from the choice function, for example

(if one exists, otherwise it returns an arbitrary object). Hence we may obtain quantifiers from the choice function, for example  was equivalent to

was equivalent to  .[3]

.[3]

However, Bourbaki's choice operator is stronger than usual: it's a global choice operator. That is, it implies the axiom of global choice.[4] Hilbert realized this when introducing epsilon calculus.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Zermelo, Ernst (1904). "Beweis, dass jede Menge wohlgeordnet werden kann". Mathematische Annalen 59 (4): 514–16. doi:10.1007/BF01445300.

- ↑ Border, Kim C. (1989). Fixed Point Theorems with Applications to Economics and Game Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26564-9.

- ↑ Bourbaki, Nicolas. Elements of Mathematics: Theory of Sets. ISBN 0-201-00634-0.

- ↑ John Harrison, "The Bourbaki View" eprint.

- ↑ "Here, moreover, we come upon a very remarkable circumstance, namely, that all of these transfinite axioms are derivable from a single axiom, one that also contains the core of one of the most attacked axioms in the literature of mathematics, namely, the axiom of choice:

, where

, where  is the transfinite logical choice function." Hilbert (1925), “On the Infinite”, excerpted in Jean van Heijenoort, From Frege to Gödel, p. 382. From nCatLab.

is the transfinite logical choice function." Hilbert (1925), “On the Infinite”, excerpted in Jean van Heijenoort, From Frege to Gödel, p. 382. From nCatLab.

References

This article incorporates material from Choice function on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.