Chlorophyll

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is a term used for several closely related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and the chloroplasts of algae and plants.[2] Its name is derived from the Greek words χλωρός, chloros ("green") and φύλλον, phyllon ("leaf").[3] Chlorophyll is an extremely important biomolecule, critical in photosynthesis, which allows plants to absorb energy from light. Chlorophyll absorbs light most strongly in the blue portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, followed by the red portion. Conversely, it is a poor absorber of green and near-green portions of the spectrum, hence the green color of chlorophyll-containing tissues.[4] Chlorophyll was first isolated and named by Joseph Bienaimé Caventou and Pierre Joseph Pelletier in 1817.[5]

Gallery

-

Chlorophyll gives leaves their green color and absorbs light that is used in photosynthesis.

-

Chlorophyll is found in high concentrations in chloroplasts of plant cells.

-

Absorption maxima of chlorophylls against the spectrum of white light.

-

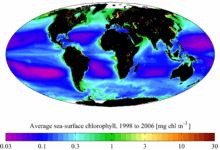

SeaWiFS-derived average sea surface chlorophyll for the period 1998 to 2006.

Chlorophyll and photosynthesis

Chlorophyll is vital for photosynthesis, which allows plants to absorb energy from light.[6]

Chlorophyll molecules are specifically arranged in and around photosystems that are embedded in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts.[7] In these complexes, chlorophyll serves two primary functions. The function of the vast majority of chlorophyll (up to several hundred molecules per photosystem) is to absorb light and transfer that light energy by resonance energy transfer to a specific chlorophyll pair in the reaction center of the photosystems.

The two currently accepted photosystem units are Photosystem II and Photosystem I, which have their own distinct reaction centres, named P680 and P700, respectively. These centres are named after the wavelength (in nanometers) of their red-peak absorption maximum. The identity, function and spectral properties of the types of chlorophyll in each photosystem are distinct and determined by each other and the protein structure surrounding them. Once extracted from the protein into a solvent (such as acetone or methanol),[8][9][10] these chlorophyll pigments can be separated in a simple paper chromatography experiment and, based on the number of polar groups between chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, will chemically separate out on the paper.

The function of the reaction center chlorophyll is to use the energy absorbed by and transferred to it from the other chlorophyll pigments in the photosystems to undergo a charge separation, a specific redox reaction in which the chlorophyll donates an electron into a series of molecular intermediates called an electron transport chain. The charged reaction center chlorophyll (P680+) is then reduced back to its ground state by accepting an electron. In Photosystem II, the electron that reduces P680+ ultimately comes from the oxidation of water into O2 and H+ through several intermediates. This reaction is how photosynthetic organisms such as plants produce O2 gas, and is the source for practically all the O2 in Earth's atmosphere. Photosystem I typically works in series with Photosystem II; thus the P700+ of Photosystem I is usually reduced, via many intermediates in the thylakoid membrane, by electrons ultimately from Photosystem II. Electron transfer reactions in the thylakoid membranes are complex, however, and the source of electrons used to reduce P700+ can vary.

The electron flow produced by the reaction center chlorophyll pigments is used to shuttle H+ ions across the thylakoid membrane, setting up a chemiosmotic potential used mainly to produce ATP chemical energy; and those electrons ultimately reduce NADP+ to NADPH, a universal reductant used to reduce CO2 into sugars as well as for other biosynthetic reductions.

Reaction center chlorophyll–protein complexes are capable of directly absorbing light and performing charge separation events without other chlorophyll pigments, but the absorption cross section (the likelihood of absorbing a photon under a given light intensity) is small. Thus, the remaining chlorophylls in the photosystem and antenna pigment protein complexes associated with the photosystems all cooperatively absorb and funnel light energy to the reaction center. Besides chlorophyll a, there are other pigments, called accessory pigments, which occur in these pigment–protein antenna complexes.

Chemical structure

Chlorophyll is a chlorin pigment, which is structurally similar to and produced through the same metabolic pathway as other porphyrin pigments such as heme. At the center of the chlorin ring is a magnesium ion. This was discovered in 1906,[11] and was the first time that magnesium had been detected in living tissue.[12] For the structures depicted in this article, some of the ligands attached to the Mg2+ center are omitted for clarity. The chlorin ring can have several different side chains, usually including a long phytol chain. There are a few different forms that occur naturally, but the most widely distributed form in terrestrial plants is chlorophyll a. After initial work done by German chemist Richard Willstätter spanning from 1905 to 1915, the general structure of chlorophyll a was elucidated by Hans Fischer in 1940. By 1960, when most of the stereochemistry of chlorophyll a was known, Robert Burns Woodward published a total synthesis of the molecule.[12][13] In 1967, the last remaining stereochemical elucidation was completed by Ian Fleming,[14] and in 1990 Woodward and co-authors published an updated synthesis.[15] Chlorophyll f was announced to be present in cyanobacteria and other oxygenic microorganisms that form stromatolites in 2010;[16][17] a molecular formula of C55H70O6N4Mg and a structure of (2-formyl)-chlorophyll a were deduced based on NMR, optical and mass spectra.[18] The different structures of chlorophyll are summarized below:

| Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll b | Chlorophyll c1 | Chlorophyll c2 | Chlorophyll d | Chlorophyll f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular formula | C55H72O5N4Mg | C55H70O6N4Mg | C35H30O5N4Mg | C35H28O5N4Mg | C54H70O6N4Mg | C55H70O6N4Mg |

| C2 group | -CH3 | -CH3 | -CH3 | -CH3 | -CH3 | -CHO |

| C3 group | -CH=CH2 | -CH=CH2 | -CH=CH2 | -CH=CH2 | -CHO | -CH=CH2 |

| C7 group | -CH3 | -CHO | -CH3 | -CH3 | -CH3 | -CH3 |

| C8 group | -CH2CH3 | -CH2CH3 | -CH2CH3 | -CH=CH2 | -CH2CH3 | -CH2CH3 |

| C17 group | -CH2CH2COO-Phytyl | -CH2CH2COO-Phytyl | -CH=CHCOOH | -CH=CHCOOH | -CH2CH2COO-Phytyl | -CH2CH2COO-Phytyl |

| C17-C18 bond | Single (chlorin) |

Single (chlorin) |

Double (porphyrin) |

Double (porphyrin) |

Single (chlorin) |

Single (chlorin) |

| Occurrence | Universal | Mostly plants | Various algae | Various algae | Cyanobacteria | Cyanobacteria |

Structure of chlorophyll a |

Structure of chlorophyll b |

Structure of chlorophyll d |

Structure of chlorophyll c1 |

Structure of chlorophyll c2 |

When leaves degreen in the process of plant senescence, chlorophyll is converted to a group of colourless tetrapyrroles known as nonfluorescent chlorophyll catabolites (NCC's) with the general structure:

These compounds have also been identified in several ripening fruits.[19]

Spectrophotometry

Measurement of the absorption of light is complicated by the solvent used to extract it from plant material, which affects the values obtained,

- In diethyl ether, chlorophyll a has approximate absorbance maxima of 430 nm and 662 nm, while chlorophyll b has approximate maxima of 453 nm and 642 nm.[20]

- The absorption peaks of chlorophyll a are at 665 nm and 465 nm. Chlorophyll a fluoresces at 673 nm (maximum) and 726 nm. The peak molar absorption coefficient of chlorophyll a exceeds 105 M−1 cm−1, which is among the highest for small-molecule organic compounds.

- In 90% acetone-water, the peak absorption wavelengths of chlorophyll a are 430 nm and 664 nm; peaks for chlorophyll b are 460 nm and 647 nm; peaks for chlorophyll c1 are 442 nm and 630 nm; peaks for chlorophyll c2 are 444 nm and 630 nm; peaks for chlorophyll d are 401 nm, 455 nm and 696 nm.[21]

By measuring the absorption of light in the red and far red regions it is possible to estimate the concentration of chlorophyll within a leaf.[22]

In his scientific paper Gitelson (1999) states, "The ratio between chlorophyll fluorescence, at 735 nm and the wavelength range 700nm to 710 nm, F735/F700 was found to be linearly proportional to the chlorophyll content (with determination coefficient, r2, more than 0.95) and thus this ratio can be used as a precise indicator of chlorophyll content in plant leaves."[23] The fluorescent ratio chlorophyll content meters use this technique.

Biosynthesis

In plants, chlorophyll may be synthesized from succinyl-CoA and glycine, although the immediate precursor to chlorophyll a and b is protochlorophyllide. In Angiosperm plants, the last step, conversion of protochlorophyllide to chlorophyll, is light-dependent and such plants are pale (etiolated) if grown in the darkness. Non-vascular plants and green algae have an additional light-independent enzyme and grow green in the darkness instead.

Chlorophyll itself is bound to proteins and can transfer the absorbed energy in the required direction. Protochlorophyllide occurs mostly in the free form and, under light conditions, acts as a photosensitizer, forming highly toxic free radicals. Hence, plants need an efficient mechanism of regulating the amount of chlorophyll precursor. In angiosperms, this is done at the step of aminolevulinic acid (ALA), one of the intermediate compounds in the biosynthesis pathway. Plants that are fed by ALA accumulate high and toxic levels of protochlorophyllide; so do the mutants with the damaged regulatory system.[24]

Chlorosis is a condition in which leaves produce insufficient chlorophyll, turning them yellow. Chlorosis can be caused by a nutrient deficiency of iron—called iron chlorosis—or by a shortage of magnesium or nitrogen. Soil pH sometimes plays a role in nutrient-caused chlorosis; many plants are adapted to grow in soils with specific pH levels and their ability to absorb nutrients from the soil can be dependent on this.[25] Chlorosis can also be caused by pathogens including viruses, bacteria and fungal infections, or sap-sucking insects.

Complementary light absorbance of anthocyanins with chlorophylls

Anthocyanins are other plant pigments. The absorbance pattern responsible for the red color of anthocyanins may be complementary to that of green chlorophyll in photosynthetically active tissues such as young Quercus coccifera leaves. It may protect the leaves from attacks by plant eaters that may be attracted by green color.[26]

Culinary use

Chlorophyll is registered as a food additive (colorant), and its E number is E140. Chefs use chlorophyll to color a variety of foods and beverages green, such as pasta and absinthe.[27] Chlorophyll is not soluble in water, and it is first mixed with a small quantity of vegetable oil to obtain the desired solution. Extracted liquid chlorophyll was considered to be unstable and always denatured until 1997, when Frank S. & Lisa Sagliano used freeze-drying of liquid chlorophyll at the University of Florida and stabilized it as a powder, preserving it for future use.[28]

Alternative medicine

Many claims are made about the healing properties of chlorophyll, but most have been disproved or are exaggerated by the companies that are marketing them. Quackwatch, a website dedicated to debunking false medical claims, has a quote from Toledo Blade (1952) which claims [29] "Chlorophyll Held Useless As Body Deodorant",[30] but later has John C. Kephart pointing out "No deodorant effect can possibly occur from the quantities of chlorophyll put in products such as gum, foot powder, cough drops, etc. To be effective, large doses must be given internally".[31]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chlorophyll. |

- Bacteriochlorophyll, related compounds in phototrophic bacteria

- Chlorophyll a, an essential chlorophyll pigment

- Chlorophyll b, also an essential chlorophyll pigment

- Chlorophyllin, a semi-synthetic derivative of chlorophyll

- Deep chlorophyll maximum

- Grow light, a lamp that promotes photosynthesis

- Chlorophyll fluorescence, to measure plant stress

References

- ↑ Chlorophyll : Global Maps. Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Retrieved on 2014-02-02.

- ↑ May, Paul. "Chlorophyll". University of Bristol.

- ↑ "chlorophyll". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Chlorophyll molecules are specifically arranged in and around photosystems that are embedded in the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts. Two types of chlorophyll exist in the photosystems: chlorophyll a and b. Speer, Brian R. (1997). "Photosynthetic Pigments". UCMP Glossary (online). University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ See:

- Delépine, Marcel (September 1951). "Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou". Journal of Chemical Education 28 (9): 454. Bibcode:1951JChEd..28..454D. doi:10.1021/ed028p454.

- Pelletier and Caventou (1817) "Notice sur la matière verte des feuilles" (Notice on the green material in leaves), Journal de Pharmacie, 3 : 486-491. On p. 490, the authors propose a new name for chlorophyll. From p. 490: "Nous n'avons aucun droit pour nommer une substance connue depuis long-temps, et à l'histoire de laquelle nous n'avons ajouté que quelques faits ; cependant nous proposerons, sans y mettre aucune importance, le nom de chlorophyle, de chloros, couleur, et φυλλον, feuille : ce nom indiquerait le rôle qu'elle joue dans la nature." (We have no right to name a substance [that has been] known for a long time, and to whose story we have added only a few facts ; however, we will propose, without giving it any importance, the name chlorophyll, from chloros, color, and φυλλον, leaf : this name would indicate the role that it plays in nature.)

- ↑ Carter, J. Stein (1996). "Photosynthesis". University of Cincinnati.

- ↑ Nature (July 5, 2013). "Unit 1.3. Photosynthetic Cells". Essentials of Cell Biology. nature.com.

- ↑ Marker, A. F. H. (1972). "The use of acetone and methanol in the estimation of chlorophyll in the presence of phaeophytin". Freshwater Biology 2 (4): 361. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1972.tb00377.x.

- ↑ Jeffrey, S. W.; Shibata, Kazuo (February 1969). "Some Spectral Characteristics of Chlorophyll c from Tridacna crocea Zooxanthellae". Biological Bulletin (Marine Biological Laboratory) 136 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2307/1539668. JSTOR 1539668.

- ↑ Gilpin, Linda (21 March 2001). "Methods for analysis of benthic photosynthetic pigment". School of Life Sciences, Napier University. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ Willstätter, Richard (1906) "Zur Kenntniss der Zusammensetzung des Chlorophylls" ([Contribution] to the knowledge of the composition of chlorophyll), Annalen der Chemie, 350 : 48-82. From p. 49: "Das Hauptproduct der alkalischen Hydrolyse bilden tiefgrüne Alkalisalze. In ihnen liegen complexe Magnesiumverbindungen vor, die das Metall in einer gegen Alkali auch bei hoher Temperatur merkwürdig widerstandsfähigen Bindung enthalten." (Deep green alkali salts form the main product of alkali hydrolysis. In them, complex magnesium compounds are present, which contain the metal in a bond that's extraordinarily resistant to alkali even at high temperature.)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Motilva, Maria-José (2008). "Chlorophylls – from functionality in food to health relevance". 5th Pigments in Food congress- for quality and health (Print). University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-10-4846-3.

- ↑ Woodward, R. B.; Ayer, W. A.; Beaton, J. M.; Bickelhaupt, F.; Bonnett, R.; Buchschacher, P.; Closs, G. L.; Dutler, H.; Hannah, J. et al. (July 1960). "The total synthesis of chlorophyll". Journal of the American Chemical Society 82 (14): 3800–3802. doi:10.1021/ja01499a093.

- ↑ Fleming, Ian (14 October 1967). "Absolute Configuration and the Structure of Chlorophyll". Nature 216 (5111): 151–152. Bibcode:1967Natur.216..151F. doi:10.1038/216151a0.

- ↑ Woodward, R. B.; Ayer, William A.; Beaton, John M.; Bickelhaupt, Friedrich; Bonnett, Raymond; Buchschacher, Paul; Closs, Gerhard L.; Dutler, Hans; Hannah, John et al. (1990). "The total synthesis of chlorophyll a" (PDF). Tetrahedron 46 (22): 7599–7659. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(90)80003-Z.

- ↑ Jabr, Ferris (August 19, 2010) A New Form of Chlorophyll?. Scientific American. Retrieved on 2012-04-15.

- ↑ Infrared chlorophyll could boost solar cells. New Scientist. August 19, 2010. Retrieved on 2012-04-15.

- ↑ Chen, Min; Schliep, Martin; Willows, Robert D.; Cai, Zheng-Li; Neilan, Brett A.; Scheer, Hugo (September 2010). "A Red-Shifted Chlorophyll". Science 329 (5997): 1318–1319. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1318C. doi:10.1126/science.1191127. PMID 20724585.

- ↑ Müller, Thomas; Ulrich, Markus; Ongania, Karl-Hans; Kräutler, Bernhard (2007). "Colorless Tetrapyrrolic Chlorophyll Catabolites Found in Ripening Fruit Are Effective Antioxidants". Angewandte Chemie 46 (45): 8699–8702. doi:10.1002/anie.200703587. PMC 2912502. PMID 17943948.

- ↑ Gross, Jeana (1991). Pigments in vegetables: chlorophylls and carotenoids. Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 0442006578.

- ↑ Larkum, edited by Anthony W. D. Larkum, Susan E. Douglas & John A. Raven (2003). Photosynthesis in algae. London: Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-6333-7.

- ↑ Cate, Thomas; Perkins, T. D. (September 2003). "Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou". Journal of Tree Physiology 23 (15): 1077–1079. doi:10.1093/treephys/23.15.1077.

- ↑ Gitelson, Anatoly A; Buschmann, Claus; Lichtenthaler, Hartmut K (1999). "The Chlorophyll Fluorescence Ratio F735/F700 as an Accurate Measure of the Chlorophyll Content in Plants". Remote Sensing of Environment 69 (3): 296. doi:10.1016/S0034-4257(99)00023-1.

- ↑ Meskauskiene R, Nater M, Goslings D, Kessler F, op den Camp R, Apel K. (23 October 2001). "FLU: A negative regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (22): 12826–12831. doi:10.1073/pnas.221252798. JSTOR 3056990. PMC 60138. PMID 11606728.

- ↑ Duble, Richard L. "Iron Chlorosis in Turfgrass". Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ Karageorgou, P.; Manetas, Y. (2006). "The importance of being red when young: Anthocyanins and the protection of young leaves of Quercus coccifera from insect herbivory and excess light". Tree Physiology 26 (5): 613–21. doi:10.1093/treephys/26.5.613. PMID 16452075.

- ↑ Adams, Jad (2004). Hideous absinthe : a history of the devil in a bottle. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-299-20000-8.

- ↑ US patent 5820916, Sagliano, Frank S. & Sagliano, Elizabeth A., "Method for growing and preserving wheat grass nutrients and products thereof", issued 1998-10-13

- ↑ Amazing Claims for Chlorophyll, Quackwatch

- ↑ Ubell, Earl (December 10, 1952) "Chlorophyll Held Useless As Body Deodorant", Toledo Blade

- ↑ Kephart, John C. (1955). "Chlorophyll derivatives—Their chemistry? Commercial preparation and uses". Journal of Ecological Botany 9: 3. doi:10.1007/BF02984956.

External links

- Oregon University of Health & Sciences

- PDF review-Chlorophyll d: the puzzle resolved

- Light Absorption by Chlorophyll – NIH books

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||