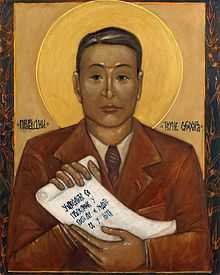

Chiune Sugihara

| Chiune Sugihara | |

|---|---|

|

Chiune Sugihara | |

| Native name | 杉原 千畝 |

| Born |

1 January 1900 Yaotsu, Gifu, Japan |

| Died |

31 July 1986 (aged 86) Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Other names | "Sempo", Pavlo Sergeivich Sugihara |

| Occupation | Vice-Consul for the Empire of Japan in Lithuania |

| Known for | Rescue of some ten thousand Jews during the Holocaust |

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Spouse(s) |

Klaudia Semionovna Apollonova (m. 1919; div. 1935) Yukiko Kikuchi (m. 1935) |

| Children | Hiroki, Chiaki, Haruki, Nobuki (only remaining son alive) |

| Awards | Righteous Among the Nations (1985) |

Chiune Sugihara (杉原 千畝 Sugihara Chiune, 1 January 1900 – 31 July 1986) was a Japanese diplomat who served as Vice-Consul for the Empire of Japan in Lithuania. During World War II, he helped several thousand Jews leave the country by issuing transit visas to Jewish refugees so that they could travel to Japan. Most of the Jews who escaped were refugees from German-occupied Poland and residents of Lithuania. Sugihara wrote travel visas that facilitated the escape of more than 6,000 Jewish refugees to Japanese territory, risking his career and his family's lives. Sugihara had told the refugees to call him "Sempo", the Sino-Japanese reading of the characters in his first name, discovering it was much easier for Western people to pronounce.[1] In 1985, Israel named him to the Righteous Among the Nations for his actions, the only Japanese national to be so honored.

Early life

Chiune Sugihara was born 1 January 1900, in Yaotsu, a rural area in Gifu Prefecture of the Chubu region to a middle-class father, Yoshimi Sugihara (杉原好水 Sugihara Yoshimi), and Yatsu Sugihara (杉原やつ Sugihara Yatsu), an upper-middle class mother. He was the second son among five boys and one girl.[2]

In 1912, he graduated with top honors from Furuwatari Elementary School, and entered Daigo Chugaku founded by Aichi prefecture (now Zuiryo high school), a combined junior and senior high school. His father wanted him to follow in his footsteps as a physician, but Chiune deliberately failed the entrance exam by writing only his name on the exam papers. Instead, he entered Waseda University in 1918 and majored in English language. At that time, he entered Yuai Gakusha, the Christian fraternity which had been founded by Harry Baxter Benninhof, a Baptist pastor. In 1919, he passed the Foreign Ministry Scholarship exam. The Japanese Foreign Ministry recruited him and assigned him to Harbin, China, where he also studied the Russian and German languages and later became an expert on Russian affairs.

Manchurian Foreign Office

When Sugihara served in the Manchurian Foreign Office, he took part in the negotiations with the Soviet Union concerning the Northern Manchurian Railroad. He quit his post as Deputy Foreign Minister in Manchuria in protest over Japanese mistreatment of the local Chinese. While in Harbin, he converted to Orthodox Christianity[3] and married a Russian woman named Klaudia Semionovna Apollonova. They divorced in 1935, before he returned to Japan, where he married Yukiko Kikuchi, who became Yukiko Sugihara (1913–2008) (杉原幸子 Sugihara Yukiko) after the marriage; they had four sons (Hiroki, Chiaki, Haruki, Nobuki). As of 2012, Nobuki is their only surviving son.[4] Chiune Sugihara also served in the Information Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and as a translator for the Japanese legation in Helsinki, Finland.[1]

Lithuania

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

| Notable individuals |

| By country |

In 1939, Sugihara became a vice-consul of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania. His other duty was to report on Soviet and German troop movements[2] and be Japan's eyes and ears in Eastern Europe as they were suspicious that Hitler wasn't being completely honest despite being allies. His mission was to find out if Germany planned an attack on the Soviets and if so, the details of said attack were to be reported to his superiors in both Berlin and Tokyo.[5]

Sugihara is said to have cooperated with Polish intelligence as part of a bigger Japanese–Polish cooperative plan.[6] As the Soviet Union occupied sovereign Lithuania in 1940, many Jewish refugees from Poland (Polish Jews) as well as Lithuanian Jews tried to acquire exit visas. Without the visas, it was dangerous to travel, yet it was impossible to find countries willing to issue them. Hundreds of refugees came to the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, trying to get a visa to Japan. At the time, on the brink of the war, Lithuanian Jews made up one third of Lithuania's urban population and half of the residents of every town as well.[7] The Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk had provided some of them with an official third destination to Curaçao, a Caribbean island and Dutch colony that required no entry visa, or Surinam (which, upon independence in 1975, became Suriname). At the time, the Japanese government required that visas be issued only to those who had gone through appropriate immigration procedures and had enough funds. Most of the refugees did not fulfill these criteria. Sugihara dutifully contacted the Japanese Foreign Ministry three times for instructions. Each time, the Ministry responded that anybody granted a visa should have a visa to a third destination to exit Japan, with no exceptions.[2]

From 18 July to 28 August 1940, aware that applicants were in danger if they stayed behind, Sugihara began to grant visas on his own initiative, after consulting with his family. He ignored the requirements and issued the Jews with a ten-day visa to transit through Japan, in violation of his orders. Given his inferior post and the culture of the Japanese Foreign Service bureaucracy, this was an unusual act of disobedience. He spoke to Soviet officials who agreed to let the Jews travel through the country via the Trans-Siberian Railway at five times the standard ticket price.

Sugihara continued to hand write visas, reportedly spending 18–20 hours a day on them, producing a normal month's worth of visas each day, until 4 September, when he had to leave his post before the consulate was closed. By that time he had granted thousands of visas to Jews, many of whom were heads of households and thus permitted to take their families with them. On the night before their scheduled departure, Sugihara and his wife stayed awake writing out visa approvals. According to witnesses, he was still writing visas while in transit from his hotel and after boarding the train at the Kaunas Railway Station, throwing visas into the crowd of desperate refugees out of the train's window even as the train pulled out.

In final desperation, blank sheets of paper with only the consulate seal and his signature (that could be later written over into a visa) were hurriedly prepared and flung out from the train. As he prepared to depart, he said, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.” When he bowed deeply to the people before him, someone exclaimed, “Sugihara. We’ll never forget you. I’ll surely see you again!”[1]

Sugihara himself wondered about official reaction to the thousands of visas he issued. Many years later, he recalled, "No one ever said anything about it. I remember thinking that they probably didn't realize how many I actually issued."[8]

The total number of Jews saved by Sugihara is in dispute, estimating about 6,000; family visas—which allowed several people to travel on one visa—were also issued, which would account for the much higher figure. The Simon Wiesenthal Center has estimated that Chiune Sugihara issued transit visas for about 6,000 Jews and that around 40,000 descendants of the Jewish refugees are alive today because of his actions.[2] Polish intelligence produced some false visas. Sugihara's widow and eldest son estimate that he saved 10,000 Jews from certain death, whereas Boston University professor and author, Hillel Levine, also estimates that he helped "as many as 10,000 people", but that far fewer people ultimately survived.[9] According to Levine's 1996 biography of Sugihara, In Search of Sugihara,[10] the Japanese diplomat issued 3,400 transit visas to the Jews.[9] Levine reports from his research of official Japanese foreign ministry documents entitled "Miscellaneous Documents Regarding Ethnic Issues: Jewish Affairs,' vol.10, 1940 Diplomatic Record Office, Japanese Foreign Ministry, Tokyo", that he discovered one list alone of "2,139 names, largely of Poles—both Jews and non-Jews—who received visas between July 9 and August 31, 1940...It is far from complete; many who received visas from Sugihara, including children, are not on it. By statistical extrapolation, it can be estimated that he helped as many as ten thousand escape, yet those who actually survived are probably no more than half that number."[9] Indeed, some Jews who received Sugihara visas failed to leave Lithuania in time, were later captured by the Germans who invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, and perished in the Holocaust.

The Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has opened to the public two documents concerning Sugihara's file: the first aforementioned document is a 5 February 1941 diplomatic note from Chiune Sugihara to Japan's then Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka in which Sugihara stated he issued 1,500 out of 2,139 transit visas to Jews and Poles; however, since most of the 2,139 people were not Jewish, this would imply that most of the visas were given to Polish Jews instead. Levine then notes that another document from the same foreign office file "indicates an additional 3,448 visas were issued in Kaunas for a total of 5,580 visas" which were likely given to Jews desperate to flee Lithuania for safety in Japan or Japanese occupied China. Moreover, there were also "some Jesuits in Vilna who were issuing Sugihara visas with seals that he had left behind and did not destroy, long after the Japanese diplomat had departed" which means that some Jews could have escaped Europe with forged visas issued under Sugihara's name.[9]

Many refugees used their visas to travel across the Soviet Union to Vladivostok and then by boat to Kobe, Japan, where there was a Russian Jewish community. Tadeusz Romer, the Polish ambassador in Tokyo, organised help for them. From August 1940 to November 1941, he had managed to get transit visas in Japan, asylum visas to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Burma, immigration certificates to the British Mandate of Palestine, and immigrant visas to the United States and some Latin American countries for more than two thousand Polish-Lithuanian Jewish refugees, who arrived in Kobe, Japan, and the Shanghai Ghetto, China.

The remaining number of Sugihara survivors stayed in Japan until they were deported to Japanese-held Shanghai, where there was already a large Jewish community. Some took the route through Korea directly to Shanghai without passing through Japan. A group of thirty people, all possessing a visa of "Jakub Goldberg", were bounced back and forth on the open sea for several weeks before finally being allowed to pass through Tsuruga.[11] Most of the around 20,000 Jews survived the Holocaust in the Shanghai ghetto until the Japanese surrender in 1945, three to four months following the collapse of the Third Reich itself.

Resignation

Sugihara was reassigned to Berlin[9] before serving as a Consul General in Prague, Czechoslovakia, from March 1941 to late 1942 in Königsberg, East Prussia and in the legation in Bucharest, Romania from 1942 to 1944. When Soviet troops entered Romania, they imprisoned Sugihara and his family in a POW camp for eighteen months. They were released in 1946 and returned to Japan through the Soviet Union via the Trans-Siberian railroad and Nakhodka port. In 1947, the Japanese foreign office asked him to resign, nominally due to downsizing. Some sources, including his wife Yukiko Sugihara, have said that the Foreign Ministry told Sugihara he was dismissed because of "that incident" in Lithuania.[9][12]

In October 1991, the ministry told Sugihara's family that Sugihara's resignation was part of the ministry's shakeup in personnel shortly after the end of the war. The Foreign Ministry issued a position paper on 24 March 2006, that there was no evidence the Ministry imposed disciplinary action on Sugihara. The ministry said that Sugihara was one of many diplomats to resign voluntarily, but that it was "difficult to confirm" the details of his individual resignation. Despite Sugihara not being the only one to supposedly resign voluntarily, Pamela Rotner Sakamoto made a very important observation, and it's that "many Japanese diplomats issued visas that saved Jews...Only a few like Sugihara saved Jews by issuing visas.".[5] Sugihara received no punishment for his insubordination by choosing to give out visas despite his orders except for the loss of his career.[13] Even though, officially, Sugihara didn't suffer any consequences for his actions other than losing his job, rumors surfaced from the Foreign Ministry that because he accepted money for the visas, he didn't need his job.[5] The ministry praised Sugihara's conduct in the report, calling it a "courageous and humanitarian decision."[12] There were post-war efforts by survivors like Yehoshua Nishri to find Sugihara but were frustrated by the Foreign Ministry's officials on technicalities involving the pronunciation and proper spelling of Sugihara's name.[5]

Later life

Sugihara settled in Fujisawa in Kanagawa prefecture with his wife and 3 sons. To support his family he took a series of menial jobs, at one point selling light bulbs door to door. He suffered a personal tragedy in 1947 when his youngest son, Haruki, died at the age of seven, shortly after their return to Japan.[5] In 1949 they had one more son, Nobuki, who is the last son alive, residing in Belgium. He later began to work for an export company as General Manager of U.S. Military Post Exchange. Utilizing his command of the Russian language, Sugihara went on to work and live a low-key existence in the Soviet Union for sixteen years, while his family stayed in Japan.

In 1968, Jehoshua Nishri, an economic attaché to the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo and one of the Sugihara beneficiaries, finally located and contacted him. Nishri had been a Polish teen in the 1940s. The next year Sugihara visited Israel and was greeted by the Israeli government. Sugihara beneficiaries began to lobby for his inclusion in the Yad Vashem memorial.

In 1985, Chiune Sugihara was granted the honor of the Righteous Among the Nations (Hebrew: חסידי אומות העולם , translit. Khasidei Umot ha-Olam) by the government of Israel. Sugihara was too ill to travel to Israel, so his wife and son accepted the honor on his behalf. Sugihara and his descendants were given perpetual Israeli citizenship.

That same year, 45 years after the Soviet invasion of Lithuania, he was asked his reasons for issuing visas to the Jews. Sugihara explained that the refugees were human beings, and that they simply needed help.

| “ | You want to know about my motivation, don't you? Well. It is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face to face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them. Among the refugees were the elderly and women. They were so desperate that they went so far as to kiss my shoes, Yes, I actually witnessed such scenes with my own eyes. Also, I felt at that time, that the Japanese government did not have any uniform opinion in Tokyo. Some Japanese military leaders were just scared because of the pressure from the Nazis; while other officials in the Home Ministry were simply ambivalent.

People in Tokyo were not united. I felt it silly to deal with them. So, I made up my mind not to wait for their reply. I knew that somebody would surely complain about me in the future. But, I myself thought this would be the right thing to do. There is nothing wrong in saving many people's lives....The spirit of humanity, philanthropy...neighborly friendship...with this spirit, I ventured to do what I did, confronting this most difficult situation—and because of this reason, I went ahead with redoubled courage.[9] |

” |

Inspired by “Lamentations, a book of the Old Testament, written by Jeremiah” which “suddenly came to [her] mind”, Yukiko Sugihara urged Chiune to issue visas to save Jewish refugees. When asked by Moshe Zupnik why he risked his career to save other people, he said simply : "I do it just because I have pity on the people. They want to get out so I let them have the visas."[8]

Sugihara died the following year at a hospital in Kamakura, on 31 July 1986. In spite of the publicity given him in Israel and other nations, he remained virtually unknown in his home country. Only when a large Jewish delegation from around the world, including the Israeli ambassador to Japan, showed up at his funeral, did his neighbors find out what he had done.[12] He may have lost his diplomatic career but he received much posthumous acclaim.[14]

Legacy and honors

Sugihara Street in Kaunas and Vilnius, Lithuania, Sugihara Street in Tel aviv, Israel, and the asteroid 25893 Sugihara are named after him. The Chiune Sugihara Memorial in the town of Yaotsu (his birthplace) was built by the people of the town in his honor. The Sugihara House Museum is in Kaunas, Lithuania.[15] The Conservative synagogue Temple Emeth, in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, has built a "Sugihara Memorial Garden"[16] and holds an Annual Sugihara Memorial Concert.

When Sugihara's widow Yukiko traveled to Jerusalem in 1998, she was met by tearful survivors who showed her the yellowing visas that her husband had signed. A park in Jerusalem is named for him. The Japanese government honored him on the centennial of his birth in 2000.[2]

A memorial to Sugihara was built in Los Angeles' Little Tokyo in 2002, and dedicated with consuls from Japan, Israel and Lithuania, Los Angeles city officials and Sugihara's son, Chiaki Sugihara, in attendance. The memorial, entitled "Chiune Sugihara Memorial, Hero of the Holocaust" depicts a life-size Sugihara seated on a bench, holding a visa in his hand and is accompanied by a quote from the Talmud: "He who saves one life, saves the entire world."[17]

He was posthumously awarded the Commander's Cross with Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta in 2007,[18] and the Commander's Cross Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland by the President of Poland in 1996.[19] Also, in 1993, he was awarded the Life Saving Cross of Lithuania. He was posthumously awarded the Sakura Award by the Japanese Canadian Cultural Center (JCCC) in Toronto in November 2014.

Biographies

- Yukiko Sugihara, Visas for Life, translated by Hiroki Sugihara, San Francisco, Edu-Comm, 1995.

- Yukiko Sugihara, Visas pour 6000 vies, traduit par Karine Chesneau, Ed. Philippe Picquier, 1995.

- A Japanese TV station in Japan made a documentary film about Chiune Sugihara. This film was shot in Kaunas, at the place of the former embassy of Japan.

- Sugihara: Conspiracy of Kindness (2000) from PBS shares details of Sugihara and his family and the fascinating relationship between the Jews and the Japanese in the 1930s and 1940s.[20]

- On 11 October 2005, Yomiuri TV (Osaka) aired a two-hour-long drama entitled Visas for Life about Sugihara, based on his wife's book.[21]

- Chris Tashima and Chris Donahue made a film about Sugihara in 1997, Visas and Virtue, which won the Academy Award for Live Action Short Film.[22]

- Passage to Freedom, by Ken Mochizuki.

Notables helped by Sugihara

- Leaders and students of the Mir Yeshiva, Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim (formally of Lubavitch/Lyubavichi, Russia) relocated to Otwock, Poland and elsewhere.

- Yaakov Banai, commander of the Lehi movement's combat unit and later an Israeli military commander.

- Joseph R. Fiszman, a noted scholar and Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Oregon.[23]

- Robert Lewin, a Polish art dealer and philanthropist.

- Leo Melamed, financier, head of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), and pioneer of financial futures.

- John G. Stoessinger, professor of diplomacy at the University of San Diego.

- Zerach Warhaftig, an Israeli lawyer and politician(notably, an Israeli Religious Minister) and a signatory of Israel's Declaration of Independence.

- George Zames, control theorist

- Bernard and Rochelle Zell, parents of business magnate Sam Zell

See also

- List of people who helped Jews during the Holocaust

- Aristides de Sousa Mendes

- Varian Fry

- Tatsuo Osako

- Giorgio Perlasca

- John Rabe

- Abdol Hossein Sardari

- Oskar Schindler

- Raoul Wallenberg

- Nicholas Winton

- Jan Zwartendijk

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Yukiko Sugihara (1995). Visas for life. Edu-Comm Plus. ISBN 0-9649674-0-5.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Tenembaum B. "Sempo "Chiune" Sugihara, Japanese Savior". The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ Keeler S (2008). "A Hidden Life: A Short Introduction to Chiune Sugihara". pravmir.com. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ (French) Anne Frank au Pays du Manga - Diaporama : Le Fils du Juste, Arte, 2012

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Sugihara, Seishiro. Chiune Sugihara and Japan's Foreign Ministry, between Incompetence and Culpability. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2001.

- ↑ "Polish-Japanese Secret Cooperation During World War II: Sugihara Chiune and Polish Intelligence". Asiatic Society of Japan. March 1995. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ Cassedy, Ellen. "We Are Here: Facing History In Lithuania." Bridges: A Jewish Feminist Journal 12, no. 2 (2007): 77-85.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sakamoto, Pamela Rotner (1998). Japanese diplomats and Jewish refugees: a World War II dilemma. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96199-0.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Levine, Hillel (1996). In search of Sugihara: the elusive Japanese diplomat who risked his life to rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-83251-8.

- ↑ On 14 August 2002, Japanese publisher Shimizu Shoin co.,Ltd was accused in court by Sugihara family about its Japanese translated book. Sugihara family claimed that more than 300 points of the book was incorrect. [Kyodo News (14 August 2002). 杉原千畝氏の妻が提訴 研究書の記述にねつ造と. 47news. Retrieved 2014-12-18.]

On 19 July 2005, the trial was reconciled. [Kyodo News (19 July 2005). 故杉原氏の妻と出版社和解 東京高裁. 47news. Retrieved 2014-12-18.]

The research society of Chiune Sugihara located in Taisho Shuppan has verified Levine's book by its Japanese translated version. The society insists more than 1,000 problems in the Japanese version. [杉原千畝研究会 (research society of Chiune Sugihara). 大正出版 杉原千畝研究会. Taisho Shuppan (publisher in Tokyo). Retrieved 2014-12-18.] - ↑ "The Asiatic Society of Japan".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Lee, Dom; Mochizuki, Ken (2003). Passage to Freedom: The Sugihara Story. New York: Lee & Low Books. ISBN 1-58430-157-0.

- ↑ Oba, Satsuki. "A Righteous Diplomat." Time International (South Pacific Edition), no. 40 (1994): 24.

- ↑ Fogel, Joshua A. "The Recent Boom in Shanghai Studies." Journal of the History of Ideas 71, no. 2 (2010): 313-33.

- ↑ "Sugihara House Museum". Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ "Inside Our Walls". Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ Velazco, Ramon G. "Chiune Sugihara Memorial, Hero of the Holocaust, Little Tokyo, Los Angeles". Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ "2007 Order of Polonia Restituta" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ "1996 Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ "Sugihara: Conspiracy of Kindness | PBS". Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ "Visas that Saved Lives, The Story of Chiune Sugihara (Holocaust Film Drama)". Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ "Visas and Virtue (2001) - IMDb". Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ Fiszman, Rachele. "In Memoriam." PS: Political Science and Politics 33, no. 3 (2000): 659-60.

Further reading

- Yutaka Taniuchi (2001), The miraculous visas -- Chiune Sugihara and the story of the 6000 Jews, New York, Gefen Books. ISBN 978-4-89798-565-7

- Seishiro Sugihara & Norman Hu (2001), Chiune Sugihara and Japan's Foreign Ministry : Between Incompetence and Culpability, University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-1971-4

- Ganor, Solly (2003). Light One Candle: A Survivor's Tale from Lithuania to Jerusalem. Kodansha America. ISBN 1-56836-352-4.

- Gold, Alison Leslie (2000). A Special Fate: Chiune Sugihara: Hero Of The Holocaust. New York: Scholastic. ISBN 0-439-25968-1.

- Kranzler, David (1988). Japanese, Nazis and Jews: The Jewish Refugee Community of Shanghai, 1938-1945. Ktav Pub Inc. ISBN 0-88125-086-4.

- Saul, Eric (1995). Visas for Life : The Remarkable Story of Chiune & Yukiko Sugihara and the Rescue of Thousands of Jews. San Francisco: Holocaust Oral History Project. ISBN 978-0-9648999-0-2.

- Iwry, Samuel (2004). To Wear the Dust of War: From Bialystok to Shanghai to the Promised Land, an Oral History (Palgrave Studies in Oral History). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6576-5.

- Paldiel, Mordecai (2007). Diplomat heroes of the Holocaust. Jersey City, N.J: distrib. by Ktav Publishing House. ISBN 0-88125-909-8.

- Sakamoto, Pamela Rotner (1998). Japanese diplomats and Jewish refugees: a World War II dilemma. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96199-0.

- Staliunas, Darius ; Stefan Schreiner; Leonidas Donskis; Alvydas Nikzentaitis (2004). The vanished world of Lithuanian Jews. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-0850-4.

- Steinhouse, Carl L (2004). RIGHTEOUS AND COURAGEOUS: HOW A JAPANESE DIPLOMAT SAVED THOUSANDS OF JEWS IN LITHUANIA FROM THE HOLOCAUST. Authorhouse. ISBN 1-4184-2079-4.

- J.W.M. Chapman, “Japan in Poland's Secret Neighbourhood War” in Japan Forum No.2, 1995.

- Ewa Pałasz-Rutkowska & Andrzej T. Romer, “Polish-Japanese co-operation during World War II ” in Japan Forum No.7, 1995.

- Takesato Watanabe, “The Revisionist Fallacy in The Japanese Media1-Case Studies of Denial of Nazi Gas Chambers and NHK's Report on Japanese & Jews Relations”in Social Sciences Review, Doshisha University, No.59,1999.

- Gerhard Krebs, Die Juden und der Ferne Osten at the Wayback Machine (archived November 5, 2005), NOAG 175-176, 2004.

- Gerhard Krebs, “The Jewish Problem in Japanese-German Relations 1933-1945” in Bruce Reynolds (ed.), Japan in Fascist Era, New York, 2004.

- Jonathan Goldstein, “The Case of Jan Zwartendijk in Lithuania, 1940” in Deffry M. Diefendorf (ed.), New Currents in Holocaust Research, Lessons and Legacies, vol.VI, Northwestern University Press, 2004.

- Hideko Mitsui, “Longing for the Other : traitors’ cosmopolitanism” in Social Anthropology, Vol 18, Issue 4, November 2010, European Association of Social Anthropologists.

- “Lithuania at the beginning of WWII”

- George Johnstone, “Japan's Sugihara came to Jews' rescue during WWII” in Investor's Business Daily, 8 December 2011.

- William Kaplan, One More Border: The True Story of One Family's Escape from War-Torn Europe, ISBN 0-88899-332-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Chiune Sugihara Centennial Celebration

- Jewish Virtual Library: Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara

- Revisiting the Sugihara Story from Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: "Forget You Not"

- Visas for Life Foundation

- Immortal Chaplains Foundation Prize for Humanity 2000 (awarded to Sugihara in 2000)

- Foreign Ministry says no disciplinary action for "Japan's Schindler"

- Foreign Ministry honors Chiune Sugihara by setting his Commemorative Plaque (Oct. 10, 2000)

- Japanese recognition of countryman

- Chiune Sempo Sugihara - Righteous Among the Nations - Yad Vashem

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - Online Exhibition Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara

- Yukiko Sugihara's Farewell on YouTube

- Sugihara Museum in Kaunas, Lithuania

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|