Chiswick Bridge

| Chiswick Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 51°28′23″N 0°16′11″W / 51.47306°N 0.26972°WCoordinates: 51°28′23″N 0°16′11″W / 51.47306°N 0.26972°W |

| Carries | A316 road |

| Crosses | River Thames |

| Locale | Mortlake and Chiswick |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Deck arch bridge |

| Material | Reinforced concrete, Portland stone |

| Total length | 606 feet (185 m) |

| Width | 70 feet (21 m) |

| Longest span | 150 feet (46 m) |

| Number of spans | 5 |

| Piers in water | 2 |

| Clearance below | 39 feet (12 m) at lowest astronomical tide[1] |

| History | |

| Designer | Sir Herbert Baker and Alfred Dryland |

| Constructed by | Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company |

| Opened | 3 July 1933 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 39,710 vehicles (2004)[2] |

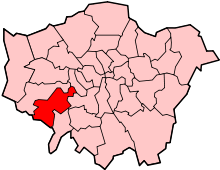

Chiswick Bridge is a reinforced concrete deck arch bridge over the River Thames in West London. One of three bridges opened in 1933 as part of an ambitious scheme to relieve traffic congestion west of London, it carries the A316 road between Chiswick on the north bank of the Thames and Mortlake on the south bank.

Built on the site of a former ferry, the bridge is 606 feet (185 m) long and faced with 3,400 tons of Portland stone. At the time of its opening its 150-foot (46 m) central span was the longest concrete span over the Thames. The bridge is possibly best known today for its proximity to the end of The Championship Course, the stretch of the Thames used for the Boat Race and other rowing races.

Background

The villages of Chiswick and Mortlake, about 6 miles (9.7 km) west of central London on the north and south banks of the River Thames, had been linked by a ferry since at least the 17th century. Both areas were sparsely populated, so there was little demand for a fixed river crossing at that point.[3]

With the arrival of railways and the London Underground in the 19th century commuting to London became practical and affordable, and the populations of Chiswick and Mortlake grew rapidly. In 1909 the Great Chertsey Road scheme was proposed, which envisaged building a major new road from Hammersmith, then on the outskirts of London, to Chertsey, 18 miles (29 km) west of central London, bypassing the towns of Kingston and Richmond.[3] However, the scheme was abandoned due to costs and arguments between various interested parties over the exact route the road should take.[3][4]

After the First World War, the population of the West London suburbs continued to grow, thanks to improved rail transport links and the growth in ownership of automobiles. In 1925, the Ministry of Transport convened a conference between Surrey and Middlesex county councils with the aim of reaching a solution to the congestion problem, and the Great Chertsey Road scheme was revived.[5] In 1927, the Royal Commission on Cross-River Traffic approved the scheme to relieve the by then chronic traffic congestion on the existing, mostly narrow, streets in the area, and on the narrow bridges at Richmond Bridge, Kew and Hammersmith.[6] The Ministry of Transport agreed to pay heavy subsidies towards the cost.[3]

A new arterial road, now the A316 road, was given Royal Assent on 3 August 1928, and construction began in 1930.[3] The construction of the road required two new bridges to be built, at Twickenham and Chiswick.[6] The proposal was authorised in 1928 and construction began in the same year.[5] The bridge, along with the newly built Twickenham Bridge and the rebuilt Hampton Court Bridge, was opened by Edward, Prince of Wales on 3 July 1933,[6] and the ferry service was permanently closed.[3]

Design

The new bridge was designed in reinforced concrete by architect Sir Herbert Baker and engineer Alfred Dryland, with additional input from Considère Constructions, at the time Britain's leading specialist in reinforced concrete construction.[6]

The bridge has concrete foundations supporting a five-arch cellular reinforced concrete superstructure.[6] The deck is supported by a concealed lattice of columns and beams rising from the arched superstructure.[5] The structure is faced with 3,400 tons of Portland stone, except for underneath the arches.[6][7] The bridge is 606 feet (185 m) long, and carries two 15-foot (4.6 m) wide walkways, and a 40-foot (12 m) wide road.[6] At the time it was built, the 150-foot (46 m) central span was the longest concrete span over the Thames.[7]

Unusually for a Thames bridge, only three of Chiswick Bridge's five spans cross the river; the shorter spans at each end of the bridge cross the former towpaths.[8] To allow sufficient clearance for shipping without steep inclines, the approach roads to the bridge are elevated from some distance back from the river.[9]

The bridge was built by the Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company at a cost of £208,284 (about £12,902,000 in 2015).[10][11] Additional costs such as building the approach roads and purchasing land brought the total cost of the bridge to £227,600 (about £14,098,000 in 2015).[5][11][n 1] The Ministry of Transport paid 75% of the cost, with Surrey and Middlesex county councils paying the remainder.

The bridge was generally well received. Country Life praised the design as "reflecting in its general design the eighteenth century Palladian tradition of Lord Burlington's famous villa at Chiswick".[12][n 2]

Present-day

Chiswick Bridge is a major transport route, and the eighth busiest of London's 20 Thames road bridges.[2] It is possibly best known for its proximity to the finishing line of The Championship Course, the stretch of the Thames used for the Boat Race and other rowing events.[7] A University Boat Race Stone on the south bank, and a brightly painted blue and black marker post near the north bank of the river, 370 feet (110 m) downstream of the bridge, mark the end of the course.[8]

The towpath under the bridge on the southern bank now forms part of the Thames Path.[8] As at 2009 the northernmost arch was used by the Tideway Scullers sculling club as storage space.[13]

Notes and references

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chiswick Bridge. |

- Notes

- ↑ Sources disagree as to what proportion of the total costs went on the construction costs of the bridge itself; Smith (2001) and Davenport (2006) both give a figure of £175,700, while other sources generally give a figure of £208,284. All sources concur that the total costs of the Chiswick Bridge part of the project came to £227,600.

- ↑ The reference to "Lord Burlington's famous villa" refers to Chiswick House, Chiswick's most significant building architecturally. The house is in fact some distance away from the bridge.

- References

- ↑ Thames Bridges Heights, Port of London Authority, retrieved 2009-05-25

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cookson 2006, p. 316

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Matthews 2008, p. 42

- ↑ Cookson 2006, p. 41

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Smith 2001, p. 41

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Davenport 2006, p. 83

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Pay, Lloyd & Waldegrave 2009, p. 93

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Matthews 2008, p. 43

- ↑ Cookson 2006, p. 67

- ↑ Cookson 2006, p. 66

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2014), "What Were the British Earnings and Prices Then? (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Country Life, 8 July 1933, quoted in Cookson 2006 p.69

- ↑ McDonnell, Colleen (2008-02-03), "Park 'needs better access'", Richmond and Twickenham Times, retrieved 2009-05-31

- Bibliography

- Cookson, Brian (2006), Crossing the River, Edinburgh: Mainstream, ISBN 1-84018-976-2, OCLC 63400905

- Davenport, Neil (2006), Thames Bridges: From Dartford to the source, Kettering: Silver Link Publishing, ISBN 1-85794-229-9

- Matthews, Peter (2008), London's Bridges, Oxford: Shire, ISBN 978-0-7478-0679-0, OCLC 213309491

- Pay, Ian; Lloyd, Sampson; Waldegrave, Keith (2009), London's Bridges: Crossing the royal river, Wisley: Artists' and Photographers' Press, ISBN 978-1-904332-90-9, OCLC 280442308

- Smith, Denis (2001), Civil Engineering Heritage London and the Thames Valley, London: Thomas Telford, ISBN 0-7277-2876-8

External links

| |||||||||