Chironex fleckeri

| Chironex fleckeri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chironex sp. | |

| Conservation status | |

| Not recognized (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Cubozoa |

| Order: | Chirodropida |

| Family: | Chirodropidae |

| Genus: | Chironex |

| Species: | C. fleckeri |

| Binomial name | |

| Chironex fleckeri Southcott, 1956 | |

| |

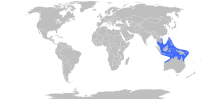

| Range of Chironex fleckeri as traditionally defined, but see text. | |

Chironex fleckeri, commonly known as sea wasp, is a species of box jellyfish found in coastal waters from northern Australia and New Guinea north to the Philippines and Vietnam.[1] It has been described as "the most lethal jellyfish in the world", with at least 63 known deaths in Australia from 1884 to 1996.[2]

Notorious for its sting, C. fleckeri has tentacles up to 3 m (9.8 ft) long covered with millions of cnidocytes which, on contact, release microscopic darts delivering an extremely powerful venom. Being stung commonly results in excruciating pain, and if the sting area is significant, an untreated victim may die in two to five minutes.[3] The amount of venom in one animal is said to be enough to kill 60 adult humans (although most stings are mild).[3]

C.fleckeri was named after North Queensland toxicologist and radiologist Doctor Hugo Flecker (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/flecker-hugo-10199 ) "On January 20th 1955, when a 5-year-old boy died after being stung in shallow water at Cardwell, north Queensland, Flecker found three types of jellyfish. One of which was an unidentified: a box-shaped jellyfish with groups of tentacles arising from each corner. Flecker sent it to Dr Ronald Southcott in Adelaide, and on December 29th 1955 Southcott published his article introducing it as a new Genus and species of lethal box jellyfish. He named it Chironex fleckeri, the name being derived from the Greek `cheiro' meaning `hand', and the Latin `nex' meaning `murderer', and `fleckeri' in honour of its discoverer." (from http://www.marine-medic.com.au/pages/medical/chironex.asp)

Description

C. fleckeri is the largest of the cubozoans (collectively called box jellyfish), many of which may carry similarly toxic venom. Its bell grows to about the size of a basketball. From each of the four corners of the bell trails a cluster of 15 tentacles. The pale blue bell has faint markings; viewed from certain angles, it bears a somewhat eerie resemblance to a human head or skull. Since it is virtually transparent, the creature is nearly impossible to see in its habitat, posing particular danger to swimmers.

When the jellyfish are swimming, the tentacles contract so they are about 15 cm long and about 5 mm in diameter; when they are hunting, the tentacles are thinner and extend to about 3 m long. The tentacles are covered with a high concentration of stinging cells called cnidocytes, which are activated by pressure and a chemical trigger; they react to proteinous chemicals. Box jellyfish are day hunters; at night they are seen resting on the ocean floor, apparently 'sleeping'. However, this 'sleeping' theory is still debated.

In common with other box jellyfish, C. fleckeri has four eye-clusters with 24 eyes. Some of these eyes seem capable of forming images, but whether they exhibit any object recognition or object tracking is debated; it is also unknown how they process information from their sense of touch and eye-like light-detecting structures due to their lack of a central nervous system. During a series of tests by leading marine biologists including Australian jellyfish expert Jamie Seymour, a single jellyfish was put in a tank. Then, two white poles were lowered into the tank. The creature appeared unable to see them and swam straight into them, thus knocking them over. Then, similar black poles were placed into the tank. This time, the jellyfish seemed aware of them, and swam around them in a figure-eight. Finally, to see if the specimen could see colour, a single red pole was stood in the tank. When the jellyfish apparently became aware of the object in its tank, it was seemingly repelled by it and remained at the far edge of the tank. Fascinated by this, the experts believed they had found a repellent for the creature and put forward the idea of red safety nets for beaches (these nets are usually used to keep the jellyfish away, but many still get through its mesh). The test was repeated, with similar results, on Irukandji jellyfish, another toxic species of box jelly.

C. fleckeri lives on a diet of prawns and small fish, and are prey to turtles, whose thick skin is impenetrable to the cnidocytes of the jellyfish.

Distribution and habitat

The medusa is pelagic and has been documented from coastal waters of Australia and New Guinea north to the Philippines and Vietnam.[1] In Australia, it is known from the northern coasts from Exmouth to Agnes Water, but its full distribution outside Australia has not been properly identified.[1] To further confuse, the closely related and also dangerously venomous Chironex yamaguchii was first described from Japan in 2009.[4] This species has also been documented from the Philippines,[4] meaning the non-Australian records of C. fleckeri need to be rechecked.

Sting

C. fleckeri is best known for its extremely powerful and occasionally fatal "sting". The sting produces excruciating pain accompanied by an intense burning sensation, like being branded with a red hot iron. In Australia, fatalities are most often caused by the larger specimens of C. fleckeri.

In December 2012, Angel Yanagihara of the University of Hawaii's Department of Tropical Medicine found the venom causes cells to become porous enough to allow potassium leakage, causing hyperkalemia which can lead to cardiovascular collapse and death as quickly as within two to five minutes with an LD50 of 0.04 mg/kg, making it the most venomous jellyfish in the world (to laboratory mice).[5] She postulated a zinc compound may be developed as an antidote.[6] Occasionally, swimmers who get stung will undergo cardiac arrest or drown before they can even get back to the shore or boat.

If a person does manage to get to safety, treatment must be administered urgently. CPR may be required; for less serious stings, treatment with ice packs and antihistamines is an effective method of pain relief.[7] Adhering tentacles should be removed carefully from the skin using protected hands or tweezers. Removed tentacles remain capable of stinging until broken down by time, and even dried and presumably dead tentacles can be reactivated if wet.

An antivenom to the box jellyfish's sting does exist. After the immediate treatment described above, it must be administered quickly. Hospitals and ambulance services near to where the jellyfish live possess it, and must be contacted as soon as possible. The jellyfish's venom is so powerful, however, that even if the victims get to safety and have the immediate treatment given, they may die before an ambulance can reach them.

In Australia, C. fleckeri has caused at least 64 deaths since the first report in 1883,[8] but most encounters appear to result only in mild envenomation.[9] Most recent deaths have been children, as their smaller body mass puts them at a higher risk of fatal envenomation.[8]

C. fleckeri and other jellyfish, including the Irukandji (Carukia barnesi), are abundant in the waters of northern Australia during the summer months (November to April or May). They are believed to drift into the aforementioned estuaries to breed. Signs like the one pictured are erected along the coast of North Queensland to warn people of such, and few people swim during this period. Some people still do, however, putting themselves at great risk. At popular swimming spots, net enclosures are placed out in the water wherein people can swim but jellyfish cannot get in, keeping swimmers safe.[10]

History of sting treatment

Until 2005, treatment involved using pressure immobilisation bandages, with the aim of preventing distribution of the venom through the lymph and blood circulatory systems. This treatment is no longer recommended by health authorities,[11] due to research which showed that using bandages to achieve tissue compression provoked nematocyst discharge.[12]

Until 2014, the application of vinegar was a recommended treatment because vinegar (4-6% acetic acid) permanently deactivates undischarged nematocysts, preventing them from opening and releasing venom.[13] This practice is no longer recommended after it was demonstrated in vitro that while vinegar deactivates unfired nematocysts, it causes already-fired nematocysts (which still contain some venom) to release the remaining venom.[14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Fenner, P. J. (2000). Chironex fleckeri – the north Australian box-jellyfish. marine-medic.com

- ↑ Fenner PJ, Williamson JA (1996). "Worldwide deaths and severe envenomation from jellyfish stings". The Medical Journal of Australia 165 (11–12): 658–61. PMID 8985452.

The chirodropid Chironex fleckeri is known to be the most lethal jellyfish in the world, and has caused at least 63 recorded deaths in tropical Australian waters off Queensland and the Northern Territory since 1884

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Biology, 7ed. Campell & Reece

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lewis, C.; Bentlage, B. (2009). "Clarifying the identity of the Japanese Habu-kurage, Chironex yamaguchii, sp nov (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropida)". Zootaxa 2030: 59–65.

- ↑ http://animals.howstuffworks.com/marine-life/jellyfish-venom2.htm

- ↑ Box jelly venom under the microscope - By Anna Salleh - Australian Broadcasting Corporation - Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ The Australian Box Jellyfish. Outback Australia Travel Guide.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Northern Territory Government (2008). Department of Health and Families. Chironex fleckeri.. Centre for Disease Control.

- ↑ Daubert, G. P. (2008). Cnidaria Envenomation. eMedicine.

- ↑ Queensland beaches stinger information page

- ↑ Queensland Government (2008). Pressure Immobilisation Technique Queensland Health

- ↑ Seymour et al. The use of pressure immobilization bandages in the first aid management of cubozoan envenomings Toxicon 2002

- ↑ Hartwick, R; Callanan V,, Williamson J. (1980). "Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri". The Medical Journal of Australia 1 (1): 15–20. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Welfare, P; Little, M; Pereira, P; Seymour, J (Mar 2014). "An in-vitro examination of the effect of vinegar on discharged nematocysts of Chironex fleckeri.". Diving and hyperbaric medicine : the journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society 44 (1): 30–4. PMID 24687483.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chironex fleckeri. |

- Beadnell CE, Rider TA, Williamson JA, Fenner PJ (May 1992). "Management of a major box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) sting. Lessons from the first minutes and hours". The Medical Journal of Australia 156 (9): 655–8. PMID 1352619.

- Barry Tobin (16 March 2010). "Dangerous Marine Animals of Northern Australia: Sea Wasp". AIMS Data Centre. Australian Institute of Marine Science. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- Distribution of Box Jellyfish in Australia